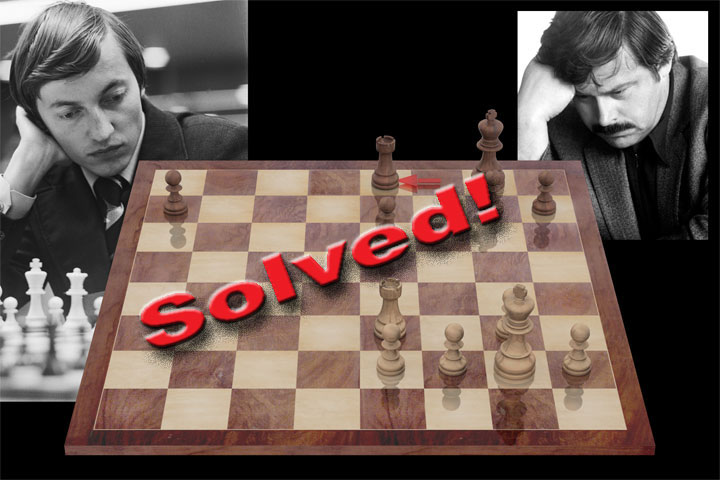

Deep rook endgame riddle

In June 1979, two months after the super event in Montreal, a small double round-robin tournament for four players was held in the small Dutch town of Waddinxveen near Gouda. The world-class players Vlastimil Hort, Lubomir Kavalek and Gennadi Sosonko were, as expected, dominated by Anatoly Karpov. Going into the final round, the World Champion had already secured victory with a score of 4/5, 1.5 points ahead of second-placed Hort.

In those years, Karpov was famous for his brilliant endgame technique, with which he achieved many technical victories even from positions with only slight advantages. Hort's position seemed extremely difficult, and Karpov did indeed win the game. the positional rook ending after 27.Rxe3 has been analysed and commented on by Jan Timman and Tibor Karolyi.

Their conclusion is that Black should give up a pawn right at the start of the endgame (instead of 27...Re8) to save his position. After this missed chance White is on the verge of victory, the annotators find no errors or significant improvements on either side.

However, analysis with a modern engine shows that a surprisingly high number of mistakes were actually made by both players after 27.Rxe3. We asked our readers if they could find some of the critical moves, or perhaps even all of them. Wolfram Schön sent us the following deep analysis. He wrote:

As we know, the World Champion was able to wrestle down his opponent from this position after 27...Re8 in 30 moves. At first glance, this appears to be another example of Karpov's famous endgame technique. From an advantageous but unwon position, he outplayed a world-class opponent who committed no serious mistakes. Therefore, this positional rook ending has attracted the attention of several commentators over the years, e.g.:

- Srdan Cvetkovic: Chess Informant 27 (Sahovski Informator, 1979)

- Jan Timman: "The Art of Chess Analysis" (Everyman Chess, 1997 org. 1993)

- Tibor Karolyi: "Endgame Virtuoso Anatoly Karpov" (New In Chess, 2007)

- Daniel Naroditsky: "Mastering Complex Endgames" (New In Chess, 2012)

Timman and Karolyi suggest Hort's first decision (27...Re8) as a possible losing move. Otherwise neither of the authors dares to describe a move by either player as a mistake and Karpov's treatment of the position is highly praised throughout.

Although Timman's analysis is essentially based on the original Dutch version of his 1980 book, it is still the best and provides insight into a number of important factors of this endgame. However, a more detailed analysis with a modern engine reveals quite a number of tactical and strategic details, previously undiscovered. This means that many moves, variations and positions have to be re-evaluated.

Summary

The result of the investigation is that both players committed a total of nine mistakes in the course of the rook ending.

This position is a key for the understanding, as it is a remarkable case of reciprocal zugzwang. In the game it was Black's turn to move and he is lost (see the analysis after 38.Ra6). However, when it's White's turn to move, he cannot lose a tempo, he is in zugzwang and cannot win (see the side line 32...g6 after 36...Rb7).

In the current pawn structure with the black setup of g7/h6, White wins by h4-h5. If then the black g-pawn moves, White has the favourable pawn exchange h5xg6. Otherwise, White gains more space on the kingside, allowing him, after some preparation, to crack Black's defence (see 31.h5).

On the other hand, if Black can play g7-g6 while the white pawn is still on h4, he sets up the line of defence with g6/h6, which is just enough to hold the game. The best White can then achieve is the key position of the previous diagram, but with him to move (see 32...g6).

Both diagrams are the main reason for seven of the errors.

And here is the full analysis. You can start an engine there to help with your analysis.

And here is the full analysis. You can start an engine there to help with your analysis.

Summary of the most important individual moves:

- 27...Re8 Black has three different systems of defence. Hort's choice to place his rook on the 7th rank is a bit passive, but fine. A pawn sacrifice with 27...a5 is an active way to hold, but needs some accurate handling in the later stage. The most flexible is 27...Kf7 28.Ra3 Ra8. In some cases Black can rely on his a-pawn, in other cases he can give it up in order to achieve a favourable pawn constellation on the kingside for a draw.

- 30...h6? A setup mistake for the black kingside pawns. 30...g6 is a correct start.

- 31.g4? Instead 31.h5! wins.

- 32...Rb7? Here 32...g6! is mandatory.

- 33.Kf3? As before, 33.h5! is necessary to win.

- 33...Rc7? Again 33...g6! is the only right way.

- 34.Ra6? Another missed chance to 34.h5! for the win.

- 36...Rb7? Here Black is in the right defensive setup, but with this unfortunate rook move he runs into the key position of reciprocal zugzwang with him to move.

- 42.Ra4? Surprisingly, a preparatory move is disastrous. Only the direct 42.g5! is correct.

- 42...Kg7? Although Black's situation seems hopeless, there is a miraculous save with 42...a6!.

- 45.Rb5?! For now White's rook is still perfectly placed on the a-file. With 45.Kf3 the white king should improve first.

- 45...Kf7?! By 45...Rc8 Black can force the white rook back to a5.

About the analyst

Wolfram Schön, born 5.6.1967, is an International Master 1987 and a grandmaster in correspondence chess since 2006. Greatest success: third place in the Correspondence Chess World Championship 2003-05.

Wolfram is a programmer and an asset manager by profession.

Previous riddles