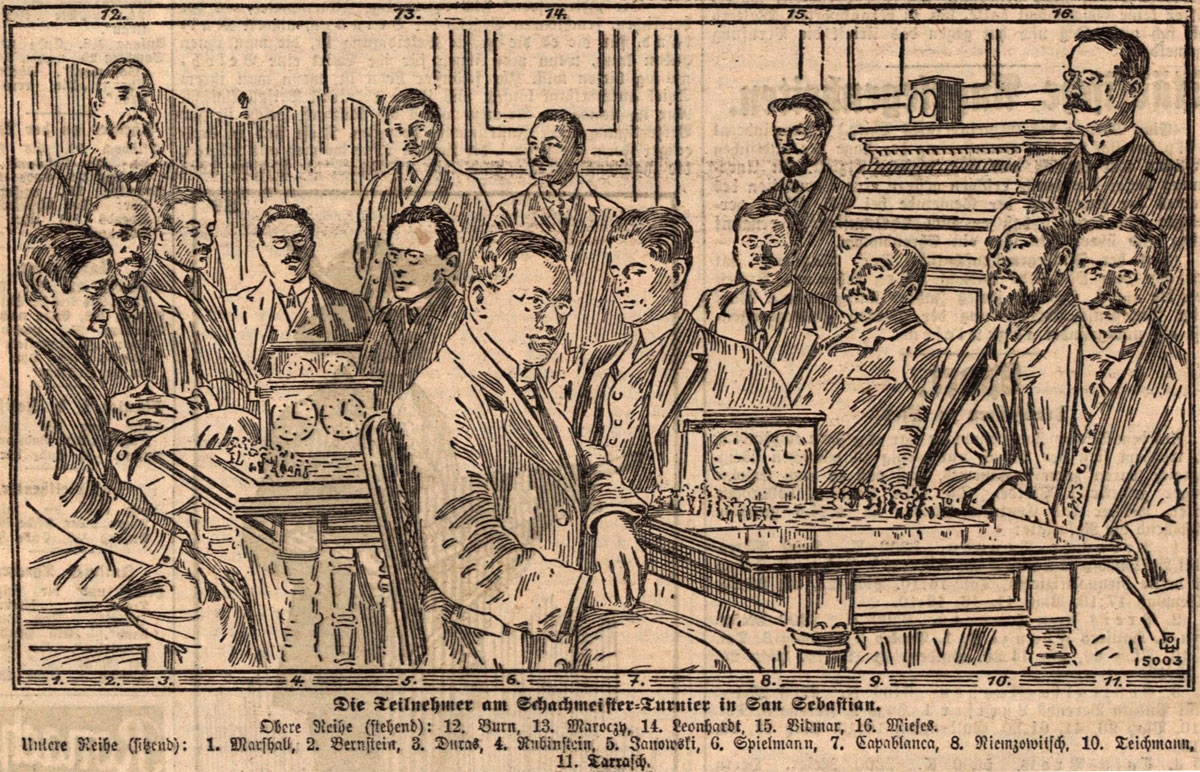

The San Sebastián tournament of 1911 was one of the strongest ever, despite the absence of World Champion Emanuel Lasker. Fifteen masters were invited who had won at least two 4th prizes in international tournaments. Somewhat surprisingly, the youngest player, 22-year-old European debutant José R. Capablanca, won the competition with 9½/14.

Drawing of the participants of the San Sebastián tournament of 1911 in the Kronen Zeitung. Rubinstein is fifth from the left (behind the chess clocks), Tarrasch seated on the right.

Drawing of the participants of the San Sebastián tournament of 1911 in the Kronen Zeitung. Rubinstein is fifth from the left (behind the chess clocks), Tarrasch seated on the right.

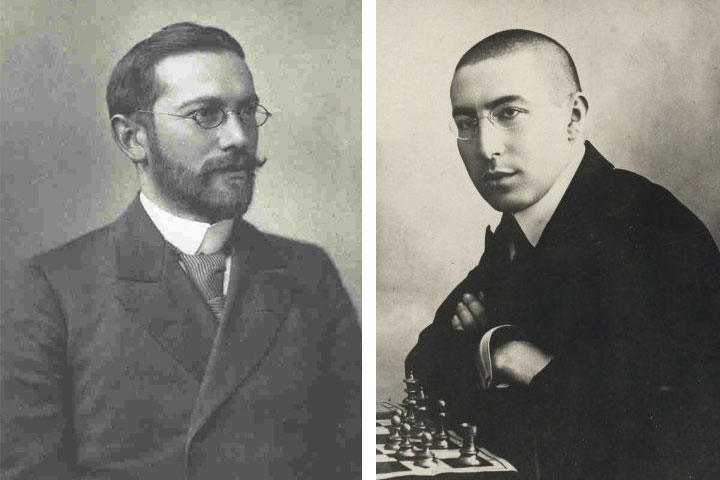

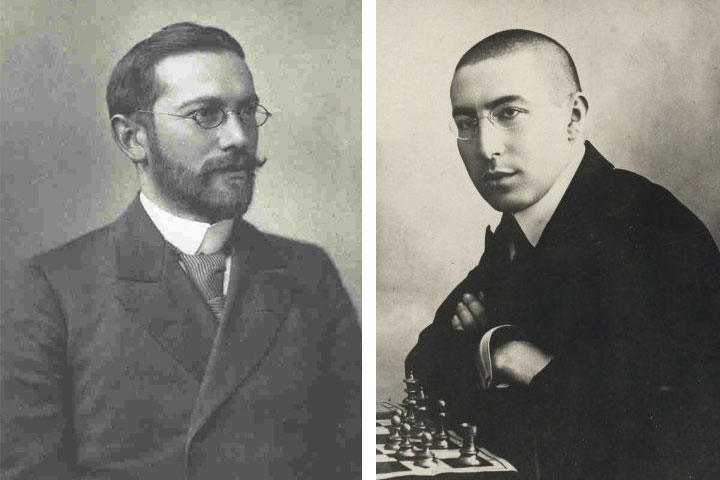

The favourite, Akiba Rubinstein from Łódź, 30 years old and co-winner of St Petersburg 1909, shared 2nd prize (with Milan Vidmar) with 9/14. He started modestly with 5 draws, but later in round 13 he defeated the Cuban in their head-to-head encounter to make it a close finish.

On the other hand, Dr Siegbert Tarrasch from Nuremberg, a doctor by profession, had achieved his most glorious triumphs some years earlier, such as in Monte Carlo in 1903. In 1908, he suffered a clear 3-8 defeat in a World Championship match against Lasker. But at the age of 48, he was still considered one of the best players. He came into this game with one win and four draws, and eventually shared 5th to 7th place with 7½/14.

Over the course of their lifelong direct encounters, Rubinstein would do very well against Tarrasch. Out of 20 games, he won 8, drew 12 and lost none. However, in their first-ever meeting here in round 6, Rubinstein got into trouble in a double rook endgame and lost a pawn on the queenside.

Click on the fan button to start an engine, and on the maximize or the layout button (second from the right) to optimize the replay window. You can also download the PGN (disk button below the notation) and analyse the endgame with the chess engine of your choice.

This famous endgame is analysed by R. Fine in his classical book "Basic Chess Endings" from 1941. Later, Levenfish/Smyslov in "The theory of rook endings" (1957), Y. Averbakh in "Turmendspiele 2" (1984), Donaldson/Minev in "The life and games of Akiva Rubinstein 1" (2006), J. Pinter in "1000 Rook Endings" (2007) and A. Panchenko in "Theory and practice of chess endings 2" (2009) approved the original annotations.

Based on Rubinstein's successful play to save his critical position, it is cited in all sources as a prime example of an active defence. Send us your assessment and analysis of this endgame. Wolfram Schön has analysed it in depth and reached amazing new conclusions – which we will publish in a week.

So what do you think? Please share your ideas, thoughts and analyses in the comments!