With contributions by Prof. Nagesh Havanur

After five games the score was level (2½-2½). But it was Bobby who had seized the initiative and held the psychological edge on and off the board. His ceaseless demands before the world championship had created enormous tension for Boris Spassky.

To add to his worries there was uncertainty whether the match itself was going to take place or not. How does one prepare for a match when the opponent does not even deign to turn up for the opening ceremony? In fairness to Bobby, he did make an apology to Spassky, but soon he was was back to his usual self, as the enfant terrible! His brinkmanship, forfeiting the second game and throwing tantrums during the third, destroyed Spassky’s mental equilibrium altogether.

To add to his woes, Boris was under tremendous pressure from the Soviet authorities to quit rather than submit to Fischer’s ever changing demands. Spassky: “A few days before the third game I spoke for half an hour on the telephone with Pavlov [Sergei Pavlov, Sports Minister of the USSR], who demanded that I issue an ultimatum that neither Fischer, nor the organisers, nor even the FIDE President, Max Euwe, could accept. That would have ended the match. So our whole conversation consisted of an unending exchange of two phrases: 'Boris Vasileyvich, you must issue the ultimatum!' - 'Sergey Pavlovich, I am going to play the match!' After this conversation I lay in bed for three hours. I was shaking. I saved Fischer, by playing the third game. In essence I signed the capitulation of the whole match.”

Decades later he summed up his dilemma, "There was only one way I could have won that match: before the third game, when Bobby began complaining, I could have refused to play on and forfeited the game. I thought of doing this, but I was the chess king and I could not go back on my word. I had promised to play this game. As a result I ruined my fighting mood..."”

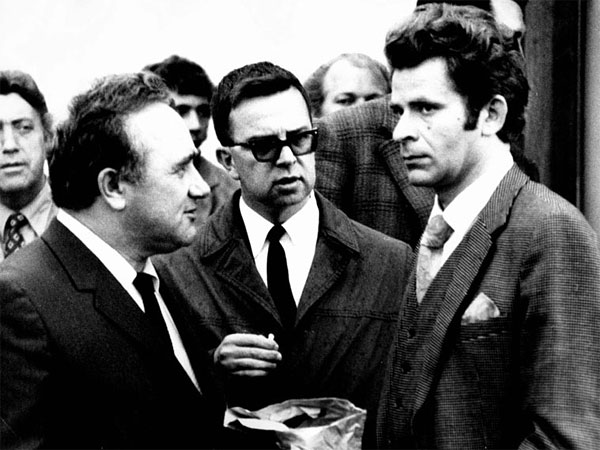

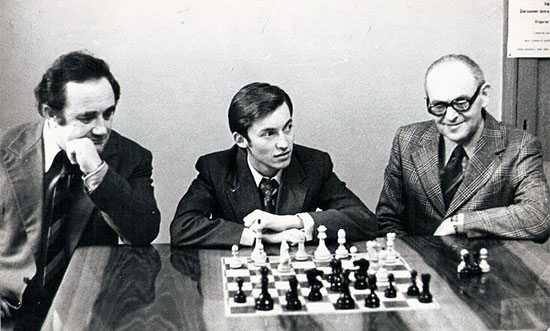

The fourth game, a tense draw, failed to restore his spirits. Efim Geller [left, here and in our title image] was Spassky’s friend and faithful second. He had prepared a line to bust the Sozin Attack that Fischer played all his life. When the position appeared on the board Boris took 45 minutes, deviated from the line they had worked on, and allowed Bobby to escape with a draw. For Geller it was particularly galling. His rivalry with Bobby went back to the 1960s, and Bobby had last beaten him in the Interzonal 1970. Then came the fifth game that broke his back. Spassky could have reveled in a sharp tactical duel, but instead was outplayed in a long maneuvering battle, and put out of his misery in the end by a blunder.

The fourth game, a tense draw, failed to restore his spirits. Efim Geller [left, here and in our title image] was Spassky’s friend and faithful second. He had prepared a line to bust the Sozin Attack that Fischer played all his life. When the position appeared on the board Boris took 45 minutes, deviated from the line they had worked on, and allowed Bobby to escape with a draw. For Geller it was particularly galling. His rivalry with Bobby went back to the 1960s, and Bobby had last beaten him in the Interzonal 1970. Then came the fifth game that broke his back. Spassky could have reveled in a sharp tactical duel, but instead was outplayed in a long maneuvering battle, and put out of his misery in the end by a blunder.

The sixth game saw the World Champion still groggy and reeling from shock after all the body blows that he had received. But what about Bobby? He could hardly play 1.e4 without running into another Sicilian mine field prepared by Geller & co. So he launched a Plan B, opening with 1.c4. That shouldn’t have been a surprise to Spassky and Geller. Bobby had played the English Opening against Polugaevsky at the 1970 Interzonal, his opponent securing a draw only after some unease with his position. Bobby repeated the same opening in the last round against Oscar Panno, who protested the change in tournament timings and forfeited his game.

All this should have put the Russians on guard. It didn’t. In the ensuing Candidates Matches with Taimanov, Larsen and Petrosian Fischer had opened only with 1.e4. So the possibility of Bobby moving anything other than the king pawn was not considered as seriously, as it should have been. Only Geller was worried as he wanted Spassky to be prepared for any eventuality. However, Boris remained complacent. Whenever his seconds asked him: “What if Bobby plays 1.d4?” he would give the same lazy answer, “I shall just play the Makogonov-Bondarevsky System. What can he get from it?” Geller for one knew how wrong he was and showed him the following game:

[Event "Moscow"] [Site "?"] [Date "1970.??.??"] [Round "?"] [White "Furman, Semyon Abramovich"] [Black "Geller, Efim P"] [Result "1-0"] [ECO "D59"] [Annotator "ChessBase"] [PlyCount "63"] [EventDate "1970.??.??"] 1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Be7 4. Nf3 Nf6 5. Bg5 h6 6. Bh4 O-O 7. e3 b6 8. cxd5 Nxd5 9. Bxe7 Qxe7 10. Nxd5 exd5 11. Rc1 Be6 12. Qa4 c5 13. Qa3 Rc8 14. Bb5 $5 $146 {Years later Geller offered a perceptive comment: "The idea is to provoke the advance of the a-pawn, which weakens both this pawn and Black's entire queenside."} (14. Be2 {is still in vogue and has stood the test of time.}) 14... a6 $2 15. dxc5 bxc5 ({After} 15... Rxc5 $6 16. O-O {Black is saddled with an isolated d-pawn and the White knight obtains posts on two ideal squares, d4 and e5.}) 16. O-O Ra7 {An awkward move. But he wants to facilitate both ...Nd7 and ...c5-c4.} ({After the game Geller thought} 16... Qb7 {was an improvement. However, Jan Timman and Ulf Andersson came up with} 17. Ba4 $1 Qb6 18. Ne5 {followed by 19.Rfd1 with pressure on the hanging pawns.}) 17. Be2 a5 { Anxious to activate the backward pawn, but it delays the development of the knight.} ({The immediate} 17... Nd7 {came to be played later.}) 18. Rc3 Nd7 19. Rfc1 Re8 $2 {Concerned with preparing the advance, d5-d4, Black overlooks that he is walking into a fatal pin.} (19... Bg4 {is preferable, though White still has a slight advantage after} 20. h3) 20. Bb5 $1 $16 Bg4 21. Nd2 $2 {White looks for a quieter way of exerting pressure on the hanging pawns, allowing Black to carry out the advance in the centre.} ({He could have won a pawn with } 21. Rxc5 $1 {, probably avoided it on account of complications from} Nxc5 22. Bxe8 Bxf3 23. Qxc5 Qg5 {However, it's smooothly parried with} 24. g3 Ra8 25. Bb5 $16) 21... d4 $1 22. exd4 cxd4 23. Qxe7 Rxe7 24. Rc8+ Kh7 25. Nb3 Ne5 26. Rd8 Rac7 $2 {preparing to exchange one pair of rooks to facilitate the advance of the d-pawn. But this plan turns out to be slow and allows White to hit back in the centre.} ({He should have acted swiftly with} 26... d3 $1 27. Bxd3+ (27. Rcc8 a4 28. Nd4 Reb7) 27... Nxd3 28. Rxd3 Be6 $11) 27. Rxc7 Rxc7 28. f4 Bd7 ({ If} 28... Nc6 $2 29. Rd6 Ne7 30. Nxd4) 29. fxe5 $2 {Anxious to neutralise the threat of ..d4-d3, White eliminates the knight first. In retrospect this was uncalled for.} (29. Bxd7 $1 Nxd7 30. Nxa5 $16 {was good enough.}) 29... Bxb5 30. Nxd4 ({not} 30. Rxd4 $2 a4 $1 {turns the tables on White} 31. Nd2 Rc1+ 32. Kf2 Rc2 33. Ke3 Rxb2 $17) 30... Rc1+ $2 {an oversight} (30... Rc5 $1 {winning the e-pawn draws.}) 31. Kf2 Rd1 32. Rd6 {White is a pawn up and has the upper hand. Geller decided not to prolong the agony and resigned.} 1-0

A curious game marred by mutual errors in the end! Yet Geller was sufficiently disturbed by the collapse of his favourite defence to Queen’s Gambit. A connoisseur of opening theory, he annotated his loss in the Chess Informant offering an improvement for Black that eventually turned out to be insufficient.

Geller and Furman, with with the young Anatoly Karpov, for whom Furman was a mentor.

Across the ocean, thousands of miles away, there sat an American grandmaster looking at the same game on his pocket chess board and his eyes lit up. That was Bobby. He had found a way of beating Boris! But how did he know Boris would play the line? The answer lay in the Red Book, the Spassky Bible that he devoured day and night.

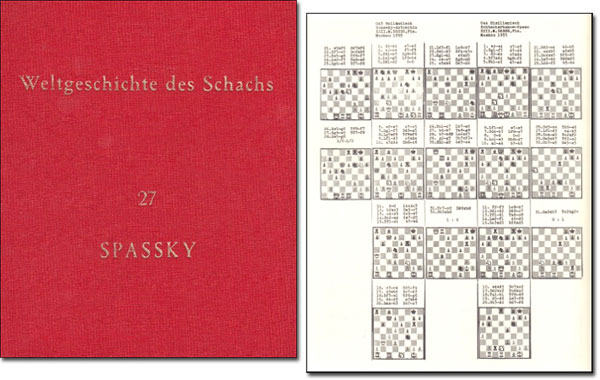

In the 1950s, Dr. Edward Wildhagen announced an ambitions project entitled “Weltgeschichte des Schachs” which means “World History of Chess”. His plan was to include every game ever played by great masters with a diagram every five moves, so that one could play over the games without setting up the board and pieces. There were 16 volumes published in this series, each dedicated to one great player. In the book Bobby found twelve games played by Spassky, none of which he lost, but there were no wins either: it was part of his drawing arsenal. The Furman-Geller game gave Bobby an idea on how to draw Boris out of his protective shell.

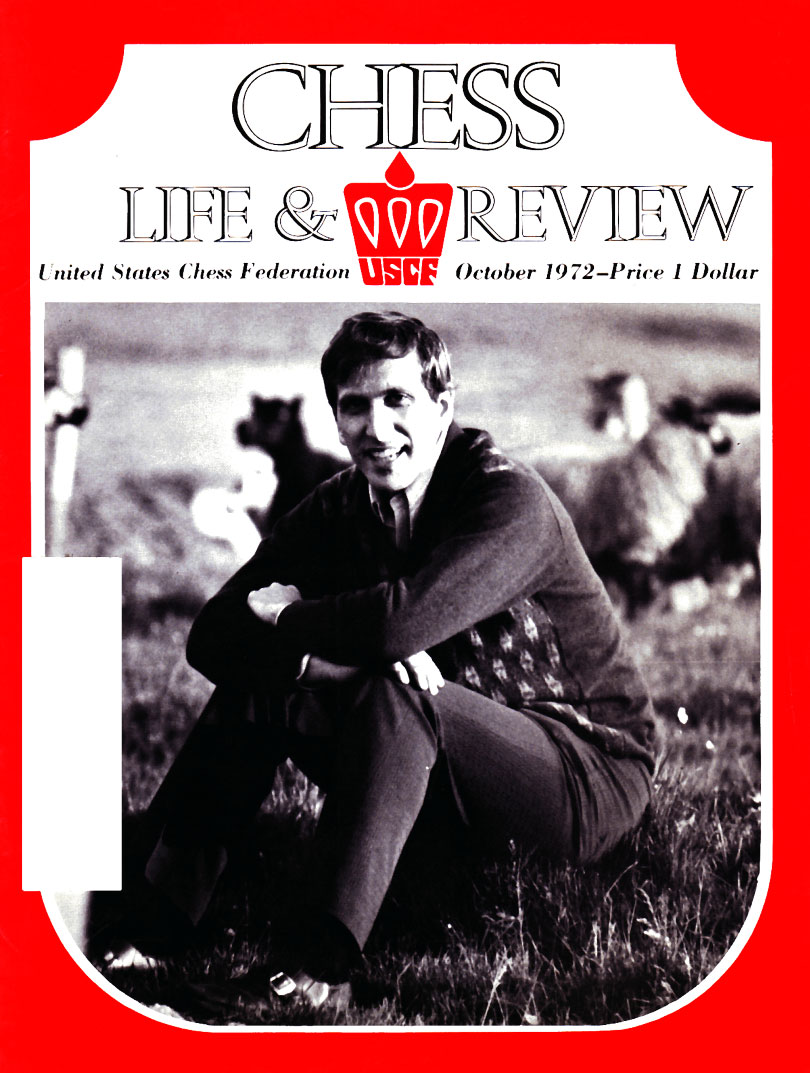

What followed in Game Six of the Match is eloquently described in a report by GM Robert Byrne in Chess Life & Review, October 1972, pages 607-609 (the pages of CL&R were numbered through for the entire year, at that time):

Just as he did in the second week of play, Bobby dominated the third week's contests, racking up 2½ points out of three for a 2-point lead in the match. Some are saying that Boris is playing badly. It isn't true—he's not getting a chance to play at all. Fischer pounces on him so sharply, usually right in the opening, that he is unable to show what he can do. How can a marvelous attacking player reveal his stuff when he cannot get a position that permits him to fire even one salvo?

The biggest blow to Spassky's self-assurance was game six. For the first time in his life, Bobby played the Queen's Gambit, having always maintained that it was "dull and a draw." And he beat Spassky, who had never lost a game with his favorite Tartakower Variation! The bare facts are no dazzling they need no embellishment. Just play over the game.

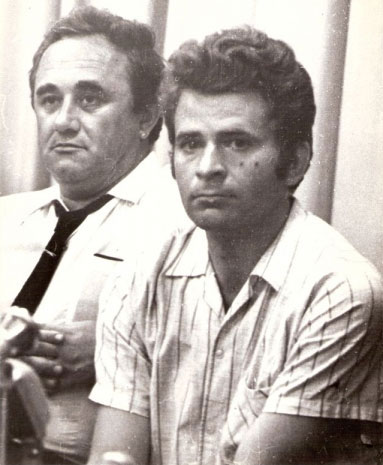

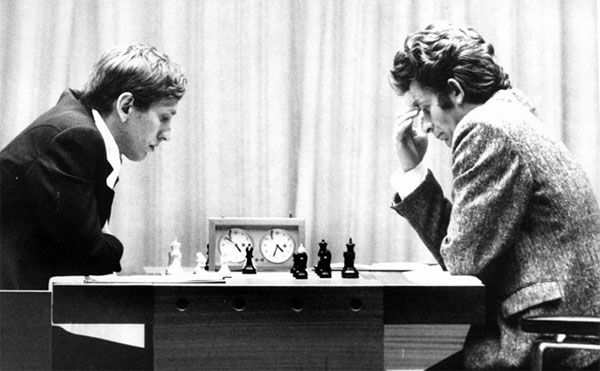

Fischer and Spassky in Reykjavik [photo Skáksamband Íslands – Icelandic Chess Federation]

[Event "Reykjavik World Championship Game 6"] [Site "Reykjavik"] [Date "1972.07.23"] [Round "6"] [White "Fischer, Robert James"] [Black "Spassky, Boris Vasilievich"] [Result "1-0"] [ECO "D59"] [WhiteElo "2785"] [BlackElo "2660"] [Annotator "Byrne,Robert"] [PlyCount "81"] [EventDate "1972.07.11"] [EventType "match"] [EventRounds "21"] [EventCountry "ISL"] [SourceTitle "MainBase"] [Source "ChessBase"] [SourceDate "1999.07.01"] 1. c4 {To my knowledge, Fischer has played this only once before, against Polugaevsky in Palma 1970. The great advantage of his going to Queenside openings is that, without any history to rely on, it was impossible for Spassky to know what to prepare.} e6 2. Nf3 d5 3. d4 Nf6 4. Nc3 Be7 {With the Black pieces in game 1, Fischer played 4 . . . B-N5 transposing into the Nimzo-Indian, but Boris, as in his match with Petrosian three years ago, prefers to stay with the normal confines of the Queen's Gambit Declined.} 5. Bg5 O-O 6. e3 h6 {Boris has been responsible for reviving this old Tartakower Variation and had never lost a game with it prior to this encounter.} 7. Bh4 b6 8. cxd5 Nxd5 9. Bxe7 Qxe7 10. Nxd5 exd5 11. Rc1 Be6 12. Qa4 c5 {Black gets maneuvering space and a free game by this advance, which, however, creates some problems guarding against possible pawn weaknesses. In the old days, it was Capablanca who forced this defense into eclipse. Will Bobby do the same now?} 13. Qa3 Rc8 14. Bb5 $1 a6 15. dxc5 bxc5 16. O-O Ra7 (16... Qb7 {has been suggested as an improvement, unpinning the pawn on c5 and preventing Fischer's 18th move. After White's necessary Bishop retreat, he would most likely continue with Rc6 followed by doubling Rooks.}) 17. Be2 Nd7 18. Nd4 {This simple positional move is quite strong, because after the exchange of a set of minor pieces the cramping effect of the Black d- and c-pawns virtually disappears while their vulnerability remains.} Qf8 {Black is intent on resolving the tension but this move is a loss of time and perhaps already the fatal mistake.} ({Dr. Euwe recommended} 18... Nf8 {but White retains a small advantage in any case.}) 19. Nxe6 fxe6 20. e4 $1 {Here is the point of the previous exchange, which only seemed to strengthen the Black pawns. But they are now weaker than ever.} d4 ({Dr. Euwe considers that the lesser of Black's evils would be the reply} 20... dxe4 {Nevertheless} 21. Bc4 Qe7 22. Rfe1 Nf6 23. f3 Kh8 24. fxe4 e5 25. Rcd1 {gives White a clear advantage, since the scattered Black pawns are all targets, and tending them prevents Black from disputing the Queen file.}) 21. f4 {While Black's pawns are immobile on the Queenside, White's will spearhead a decisive attack on the other side.} Qe7 (21... e5 22. fxe5 Qe7 23. e6 {is ruinous for Black.}) 22. e5 Rb8 23. Bc4 Kh8 ({After} 23... Nb6 $2 24. Qb3 {wins a pawn for White at once.}) 24. Qh3 Nf8 ({ After} 24... Rxb2 25. Bxe6 {there is no way to reinforce the lone Rook on the seventh rank, while the advance of the White pawn spearhead will quickly wreck the enemy king position. Now that White is shifting to the kingside onslaught, Black is lost anyway.}) 25. b3 a5 26. f5 exf5 27. Rxf5 {The f-file will be the main route of the attack. The threat is Rf7, winning the queen for rook and bishop.} Nh7 28. Rcf1 ({Not} 28. Rf7 Ng5 {winning the exchange, but now Rf7 is again a real threat.}) 28... Qd8 29. Qg3 Re7 30. h4 Rbb7 31. e6 {The pressure mounts. All Spassky can do about it is to crouch in terror on the second rank. He cannot use White's last move to get in Nf6 because Bobby is just waiting to sacrifice the exchange at f6, thus fatally denuding the black king.} Rbc7 ({If} 31... Qc7 {White mates in four starting with} 32. Rf8+) 32. Qe5 Qe8 33. a4 Qd8 34. R1f2 Qe8 35. R2f3 Qd8 36. Bd3 {Fischer's last three moves did nothing but mark time, for what reason I don't know, except perhaps to demonstrate sadistically that Black is almost in zugzwang. The present move, however, threatens Qe4, to which there is no defense.} Qe8 37. Qe4 Nf6 ({A quicker way to go was} 37... Rxe6 $2 38. Rf8+ Nxf8 39. Rxf8+ Qxf8 40. Qh7#) 38. Rxf6 $1 {This sets the seal on the win, leaving only a few grisly details.} gxf6 39. Rxf6 Kg8 40. Bc4 Kh8 41. Qf4 {resigns.} ({On} 41. Qf4 Rc8 ({And if} 41... Kg8 42. Qxh6 {leaves Black no recourse against} -- 43. Rg6+ ) 42. Rxh6+ Kg8 43. Qg4+ Rg7 44. e7+ Qf7 45. Qxc8#) 1-0

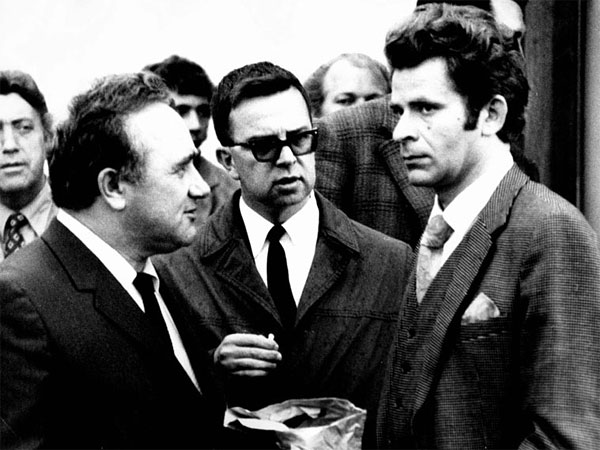

Game six was a classic that Miguel Najdorf, above in the middle, during the match in Reykjavik, likened to a symphony by Mozart! The sixth game has been annotated by a number of contemporaries like Samuel Reshevsky, Reuben Fine, Svetozar Gligoric, C.H.O’D Alexander and others.

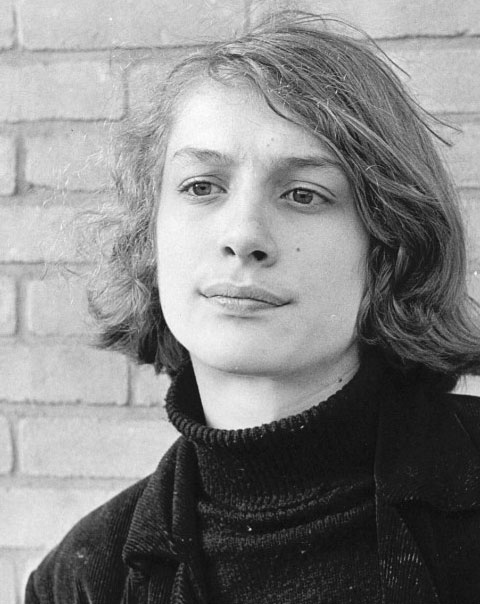

Around the same time young Jan Timman [above in a 1968 picture by Chess Diagonals] made an independent investigation of the whole game, and his example was emulated by Yasser Seirawan and Graham Burgess who also provided a useful correction to previous analysis. The last word on it all was by Garry Kasparov. ChessBase offers an update:

[Event "Reykjavik World Championship Game 6"] [Site "?"] [Date "1972.07.23"] [Round "?"] [White "Fischer, Robert James"] [Black "Spassky, Boris V"] [Result "1-0"] [ECO "D59"] [WhiteElo "2785"] [BlackElo "2660"] [Annotator "ChessBase"] [PlyCount "81"] [EventDate "1972.??.??"] 1. c4 {A surprise! Fischer had played 1.e4 all his life. Well, almost. He did play this move against Polugaevsky in 1970 Interzonal and it was a draw.} e6 2. Nf3 d5 {Spassky hopes for a transposition to Queen's Gambit Declined, an opening with which he has a lot of experience} 3. d4 {Fischer readily obliges as he has a novelty in mind.} Nf6 4. Nc3 Be7 5. Bg5 O-O 6. e3 h6 {The Tartakower Variation also carries the names of Soviet masters, Makogonov and Bondarevsky who contributed to it. Under Bondarevsky, his mentor's influence Boris also used it, never losing a single game.} 7. Bh4 b6 8. cxd5 Nxd5 9. Bxe7 Qxe7 10. Nxd5 exd5 11. Rc1 Be6 12. Qa4 c5 13. Qa3 Rc8 {[#]} 14. Bb5 $5 { Furman's novelty with which he beat Geller in Moscow 1970.The idea is to discourage ...Nb8-d7 supporting c5.} (14. Be2 {is standard.}) 14... a6 $2 ({If } 14... Nd7 15. Bxd7 Bxd7 16. dxc5 bxc5 17. O-O {followed by Rfd1 with pressure on Black's queenside pawns.}) ({After his defeat to Furman Geller found} 14... Qb7 $1 15. dxc5 bxc5 16. Rxc5 Rxc5 17. Qxc5 Na6 $1 {an idea that he employed with success against Timman in Hilversum 1973.}) 15. dxc5 bxc5 ( 15... Rxc5 16. O-O {leaves Black with an isolated d-pawn and cedes key squares, d4 and e5, to the white knight.}) 16. O-O Ra7 $2 {Now the rook and queen defend each other and Black also threatens 17...axb5, not to mention ...c5-c4. Yet it is inadequate.} ({Geller's idea} 16... Qb7 {is also not feasible on account of} 17. Ba4 {Black is underdeveloped and advancing the c-pawn only opens lines for White.} c4 18. Nd4 Qb6 19. Rfd1 Nd7 20. Nxe6 Qxe6 21. e4 $16) ( {However, Donner's suggestion} 16... Nc6 {is playable, though White has good play against the hanging pawns.} 17. Bxc6 Rxc6 18. Ne5 Rc7 19. Rfd1 $14) ({ The same goes for Larsen's} 16... Qa7 {and White has similar pressure on those pawns.} 17. Be2 ({Not} 17. Ba4 $2 a5 $1) 17... Nd7 18. Rfd1 $14) 17. Be2 { So far the game has followed Furman-Geller, Moscow 1970.} Nd7 ({Geller had tried} 17... a5 {and was outplayed after} 18. Rc3 Nd7 19. Rfc1 Re8 20. Bb5) 18. Nd4 $1 Qf8 $2 {Anxious to get away from the pin, Boris falls back on passive defence.} ({After} 18... Nf6 $1 19. Nb3 {Kasparaov proposed} Rac7 $1 $13 { (threatening...d5-d4) with a complex middlegame.} ({Seirawan's} 19... c4 20. Qxe7 Rxe7 21. Nd4 a5 $11 {is also good enough to hold the position.})) 19. Nxe6 fxe6 20. e4 $1 {probing Black's pawn centre at its most vulnerable point.[#]} d4 $2 {This move, opening the a2-g8 diagonal for the bishop plays into White's hands.} ({Tal came up with the right idea,} 20... c4 {But after} 21. Qh3 { he and other commentators couldn't find a reasonable plan for Black. Decades later in the computer era Kasparov found} Rc6 $1 ({Not} 21... Nc5 $6 22. b4 cxb3 23. axb3 {liquidates the c4 pawn and keeps pressure on Black (Graham Burgess).}) 22. b3 Nb6 {However, White still enjoys initiative on account of Black's vulnerable pawns.} 23. Rfd1 $14) 21. f4 Qe7 22. e5 Rb8 $6 ({On} 22... Nb6 {Kasparov gives} 23. Qd3 $1 (23. f5 {allows Black counterchances with} c4) 23... Nd5 24. Qe4 Qf7 25. f5 Ne3 26. fxe6 Qxe6 27. Bd3 Rf7 28. Qh7+ Kf8 29. Rxf7+ Qxf7 30. Bc4 $1 Nxc4 31. Rf1 $18) 23. Bc4 Kh8 ({After} 23... Nb6 $2 { White wins a pawn with} 24. Qb3 $1 {-Jan Timman}) 24. Qh3 Nf8 ({Black could have tried the more active} 24... Rxb2 25. Bxe6 Rab7 {But after} 26. Rce1 $16 { White should prevail according to Kasparov.}) 25. b3 a5 26. f5 exf5 27. Rxf5 Nh7 (27... Ng6 $2 {loses to} 28. Qg3 $1 ({The careless} 28. Rf7 $2 {is met by} Qg5 $1) 28... Qe8 29. Rcf1 {followed by e5-e6.}) (27... Ne6 $2 {is no worse.} 28. Bxe6 Qxe6 29. Rf8+ $18) 28. Rcf1 ({White also has to be vigilant.} 28. Rf7 $2 Ng5 29. Rxe7 Nxh3+ 30. gxh3 Rxe7 $19) 28... Qd8 ({If} 28... Rf8 $2 29. Rxf8+ Nxf8 30. Qc8 $18) 29. Qg3 Re7 30. h4 $1 {After this move neither the black queen nor the knight can use g5 as a springboard.} (30. Rf7 $2 Rxf7 31. Rxf7 Qg5 {would have given Black a breather.}) 30... Rbb7 31. e6 Rbc7 32. Qe5 Qe8 33. a4 Qd8 34. R1f2 Qe8 ({Or} 34... d3 $2 35. Rd2 $18) 35. R2f3 Qd8 36. Bd3 Qe8 (36... Qg8 {only leads to a suffocating end.} 37. Rf7 Rxf7 38. exf7 Rxf7 39. Bc4 $18) 37. Qe4 $1 Nf6 (37... Rxe6 $4 {is worse.} 38. Rf8+ $1 Nxf8 39. Rxf8+ Qxf8 40. Qh7#) 38. Rxf6 $1 $18 gxf6 39. Rxf6 Kg8 40. Bc4 Kh8 41. Qf4 1-0

Here are the times for game six, as recorded by Lawrence Stevens, who visited the match in Reykjavik and jotted them down from the video screens:

|

Game 6, July 23rd, 1972 Fischer Spassky |

12. Qa4 (0:14) c5 (0:12) 13. Qa3 (0:14) Rc8 (0:16) 14. Bb5 (0:15) a6 (0:19) 15. dxc5 (0:19) bxc5 (0:23) 16. 0-0 (0:20) Ra7 (0:36) 17. Be2 (0:23) Nd7 (0:52) 18. Nd4 (0:28) Qf8 (1:11) 19. Nxe6 (0:39) fxe6 (1:11) 20. e4 (0:42) d4 (1:13) 21. f4 (0:47) Qe7 (1:19) 22. e5 (0:51) Rb8 (1:23) 23. Bc4 (1:02) Kh8 (1:33) 24. Qh3 (1:03) Nf8 (1:36) 25. b3 (1:08) a5 (1:36) 26. f5 (1:12) exf5 (1:38) 27. Rxf5 (1:12) Nh7 (1:42) |

28. Rcf1 (1:15) Qd8 (1:48) |

This game had an unintended aftermath. When Boris returned despondent after the game, Geller asked him why he had not played 14…Qb7 that could have refuted the entire concept of 14.Bb5!? After all he had analysed the whole variation with Boris during their preparation for the match. The world champion had not cared to remember and in any case it was the last line he was prepared to see on that fateful day. A year later Jan Timman tried the same thing against Geller, and the mine that had been set for Fischer exploded. Here is the game:

[Event "Hilversum"] [Site "?"] [Date "1973.??.??"] [Round "?"] [White "Timman, Jan H"] [Black "Geller, Efim P"] [Result "0-1"] [ECO "D59"] [WhiteElo "2480"] [BlackElo "2590"] [Annotator "ChessBase"] [PlyCount "72"] [EventDate "1973.??.??"] 1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Be7 4. Nf3 Nf6 5. Bg5 O-O 6. e3 h6 7. Bh4 b6 8. cxd5 Nxd5 9. Bxe7 Qxe7 10. Nxd5 exd5 11. Rc1 Be6 12. Qa4 c5 13. Qa3 Rc8 14. Bb5 $5 { Furman's novelty that he introduced against Geller in Moscow1970. The move became famous after Fischer beat Spassky with it in Game Six, World Championship 1972. [#]} ({The standard} 14. Be2 {is still in vogue and has stood the test of time.}) 14... Qb7 $1 $146 {A brilliant move that calls into question Furman's novelty. The immediate threat is to encircle the White bishop with...c5-c4. So White has no time to castle.} ({After} 14... a6 $2 15. dxc5 bxc5 16. O-O Ra7 17. Be2 {Black has to fight for equality as shown in the games, Furman-Geller, 1970 and Fischer-Spassky, 1972.}) 15. dxc5 bxc5 16. Rxc5 Rxc5 17. Qxc5 {[#]} Na6 $1 {The refutation of White's play. Geller showed it all to Spassky during their preparation for the World Championship Match.} 18. Bxa6 ({If} 18. Qc6 $2 Qxc6 19. Bxc6 Rb8 $1 20. b3 ({or} 20. O-O Rxb2 $17) 20... Rc8 {wins the exchange.}) 18... Qxa6 {with a new threat on the horizon, 19... Rc8} 19. Qa3 Qc4 20. Kd2 $2 (20. Qc3 {was the lesser evil. After} Rb8 $1 ({not } 20... Qxa2 $2 21. O-O {lets White off the hook.}) 21. Qxc4 dxc4 22. b3 cxb3 23. axb3 Rxb3 24. O-O Rb2 $15 {Black has a slight plus on account of the passed pawn.}) 20... Qg4 21. Rg1 d4 $1 {opening up lines against the White king } 22. Nxd4 ({If} 22. exd4 Rb8 {Black threatens 23...Bd5 among other things.}) 22... Qh4 23. Re1 Qxf2+ 24. Re2 Qf1 25. Nxe6 fxe6 26. Qd6 {White had to stop... Rd8+.} Kh8 27. e4 Rc8 28. Ke3 Rf8 29. Rd2 (29. Kd2 {is also met by the same move} e5 $1) 29... e5 $1 $19 30. Qxe5 Qe1+ 31. Re2 Qg1+ 32. Kd3 Rd8+ 33. Kc3 Qd1 34. Qb5 Qd4+ 35. Kc2 a6 36. Qxa6 Qc5+ {Played with youthful energy by Geller!} 0-1

It’s a pity that Spassky did not benefit from Geller’s discovery. As for Bobby, he wisely refrained from repeating Furman’s novelty during the rest of the match.

Opening theory has advanced a lot since 1972, but if you want to learn how to play the Queens Gambit, you can do it from one of the best possible authorities: Garry Kasparov:

Robert Byrne in Reykjavik wrote:

"It may have looked as though Boris has something going for him in the 7th game, but it was all sophisticated teasing on Fischer's part. He marched confidently through the complex labyrinth of his prepared analysis, which allowed Boris assorted potshots to prevent Black from castling, but nothing else of more than ephemeral value. Soon Boris found himself in full retreat, a pawn down and with a lost game. Had Fischer not fallen prey to overconfidence, he would have won easily for a total shutout week, instead of giving up a half point."

Here is the game, with comments by Robert Byrne in Chess Life and Review, October 1972, pp. 608-609.

[Event "Reykjavik World Championship (7)"] [Site "Reykjavik"] [Date "1972.07.25"] [Round "7"] [White "Spassky, Boris Vasilievich"] [Black "Fischer, Robert James"] [Result "1/2-1/2"] [ECO "B97"] [WhiteElo "2660"] [BlackElo "2785"] [Annotator "Byrne,Robert"] [PlyCount "97"] [EventDate "1972.07.11"] [EventType "match"] [EventRounds "21"] [EventCountry "ISL"] [SourceTitle "MainBase"] [Source "ChessBase"] [SourceDate "1999.07.01"] 1. e4 {Fischer's terrific defenses to 1.d4 have driven the champion to this.} c5 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 a6 {The Najdorf Sicilian is such a favorite with Bobby that he is quite willing to forego the surprise value of something else for the opportunity of using it.} 6. Bg5 e6 7. f4 Qb6 { Beginners' books are always spouting a lot of nonsense about the evils of snatching the QNP with the Queen, but he who wins a pawn and runs away has a won endgame. Though stormed at with shot and shell, the "poisoned pawn" variation still holds its own, as Fischer demonstrates.} 8. Qd2 Qxb2 9. Nb3 Qa3 {Long preferred is 9.Nc6, but the idea contained in this move is surely stronger. As will be seen, Black must have his QP defended at the 14th move in order to carry out a sharp combination.} 10. Bd3 ({Under these circumstances, it is bet-ter to take the positional course} 10. Bxf6 gxf6 11. Be2) 10... Be7 11. O-O h6 $1 {Virtually forcing White into an unfavorable combination, since 12 BxN, BxB yields him nothing for the sacrificed Pawn.} 12. Bh4 Nxe4 $1 { The success of this little combination depends on the status of the respective positions after Fischer's 17th move.} 13. Nxe4 Bxh4 14. f5 {The only chance to put Black's defense to the test.} (14. Nxd6+ $2 Qxd6 15. Bb5+ Ke7 {merely throws away stuff for nothing.}) 14... exf5 15. Bb5+ {Nobody can say he isn't trying, but succeeding is another matter.} axb5 16. Nxd6+ {[#]} Kf8 (16... Ke7 {is unreliable:} 17. Qe3+ Kxd6 (17... Kf6 18. Nxf5 $1 Bxf5 19. Rxf5+ Kxf5 20. Rf1+ Kg6 21. Qe4+ Kh5 22. g4+ Kg5 23. Qf5# {is another possibility to be avoided.}) 18. Rad1+ Kc7 19. Qe5+ Kb6 20. Qd4+ {and White has at least a perpetual check, if not more.}) 17. Nxc8 Nc6 18. Nd6 {This is a clear admission of bankruptcy} ({but the more threatening-looking} 18. Qd7 {will not save Spassky's game either:} g6 19. Nd6 ({White can try} 19. Qxb7 {but then} Qa6 {compels the exchange of Queens, once again giving Bobby an easily won endgame.}) 19... Be7 20. Nxb5 (20. Nxf5 Qa7+ 21. Nfd4 (21. Kh1 Rd8 22. Qc7 gxf5 {is an unsound piece sacrifice.}) 21... Nxd4 22. Qxd4 Qxd4+ 23. Nxd4 Bc5 { is also a hopeless endgame.}) 20... Qa6 21. Qd3 {is a clear pawn-down position for Spassky, with nothing to show for it.}) 18... Rd8 19. Nxb5 Qe7 ({The text move, which is, I guess, still part of Bobby's prepared analysis, is stronger than} 19... Rxd2 20. Nxa3 Rd5 21. Nc4 g6 22. Rad1 Rxd1 23. Rxd1 Ke7 24. Nc5 { which gives White some chances to hold the ending.}) 20. Qf4 g6 21. a4 { If White can exchange the QRP he will eliminate a weakness and develop some Queenside play.} Bg5 22. Qc4 Be3+ 23. Kh1 f4 24. g3 g5 25. Rae1 Qb4 {Now the exchange of Queens is forced under very favorable conditions.} 26. Qxb4+ Nxb4 27. Re2 Kg7 {This is a good move,} ({but} 27... Nc6 {would have been equally effective in denying Spassky counterplay.}) 28. Na5 b6 29. Nc4 Nd5 30. Ncd6 Bc5 $2 {Bobby made the last three moves at a blitz clip, for no reason at all. It was unnecessary to retreat the Bishop from its strong position, since} (30... Kg6 {would have eliminated the threat of c4 followed by Nf5+. Then} 31. Nxf7 $2 Kxf7 32. c4 Kg6 33. cxd5 Rxd5 {would have left White without a prayer.}) { Now Spassky gets the opportunity to trade off the Bishop and escape from the bind of the Kingside pawns.} 31. Nb7 Rc8 32. c4 Ne3 33. Rf3 Nxc4 34. gxf4 g4 35. Rd3 h5 36. h3 Na5 37. N7d6 Bxd6 38. Nxd6 Rc1+ 39. Kg2 Nc4 40. Ne8+ Kg6 41. h4 $1 {[%cal Re2e5,Re5g5,Re8f6] [#]A brilliant sealed move by the champion, which setus up a bind around the King and assures a draw. For a while Najdorf was running around telling people that the move even wins for White. But it isn't that good.} f6 {There was no way of omitting this in view of the threat Rd5-g5+ and Nf6.} 42. Re6 Rc2+ 43. Kg1 Kf5 (43... Kf7 {could have led to an amusing perpetual check by} 44. f5 Rxe8 45. Rd7+ Kf8 46. Rxf6+ {etc.}) 44. Ng7+ Kxf4 45. Rd4+ Kg3 46. Nf5+ Kf3 47. Ree4 Rc1+ 48. Kh2 Rc2+ 49. Kg1 {The Black King has run out the string and anything but the perpetual check would be suicidal for Black. A point thrown away for Bobby.} 1/2-1/2

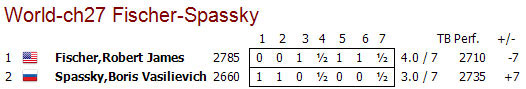

So this was the stand in the Match of the Century after game seven, which was completed on July 26, 1972, exactly forty-five years ago.

– To be continued –

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (1)

In the final week of June 1972 the chess world was in turmoil. The match between World Champion Boris Spassky and his challenger Bobby Fischer was scheduled to begin, in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, on July 1st. But there was no sign of Fischer. The opening ceremony took place without him, and the first game, scheduled for July 2nd, was postponed. Then finally, in the early hours of July 4th, Fischer arrived. Frederic Friedel narrates.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (2)

The legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer was staged in the Laugardalshöllin in Reykjavik. This is Iceland’s largest sporting arena, seating 5,500, but also the site for concerts – Led Zeppelin, Leonard Cohen and David Bowie all played there. 45 years after the Spassky-Fischer spectacle Frederic Friedel visited Laugardalshöllin and discovered some treasures there.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (3)

On July 11, 1992 the legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer finally began. Fischer arrived late, due to heavy traffic. To everybody's surprise he played a Nimzo instead of his normal Gruenfeld or King's Indian. The game developed along uninspired lines and most experts were predicting a draw. And then, on move twenty-nine, Fischer engaged in one of the most dangerous gambles of his career. "One move, and we hit every front page in the world!" said a blissful organiser.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (4)

7/16/2017 – The challenger, tormented by the cameras installed in the playing hall, traumatically lost the first game of his match against World Champion Boris Spassky. He continued his vigorous protest, and when his demands were not met Fischer did not turn up for game two. He was forfeited and the score was 0-2. Bobby booked a flight back to New York, but practically at the very last moment decided to play game three – in an isolated ping-pong room!

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (5)

7/21/2017 – After three games in the Match of the Century the score was 2:1 for the reigning World Champion. In game four Spassky played a well-prepared Sicilian and obtained a raging attack. Fischer defended tenaciously and the game was drawn. Then came a key game, about which the 1972 US Champion and New York Times and Chess Life correspondent GM Robert Byrne filed reports. In Reykjavik chess fan Lawrence Stevens from California did something extraordinary: he manually recorded the times both players had spent on each move.

| Advertising |