We take up our narrative of the Match of the Century after game three. Fischer had lost game one with a very risky move (BxPh2) and had not appeared for game two. He then went on to defeat Spassky with the black pieces in an inspired game three.

A remarkable visitor to the World Championship in 1972 was Lawrence Stevens, who arrived in Reykjavik just before game two and started recording the move times of the games. Here's how he describes this:

The player’s clocks could be seen, from time to time, on the closed-circuit black-and-white TV system in the hall. It served the lobby, the cafeteria, and the playing hall, and displayed a view of what looked like a wallboard with the pieces perfectly aligned, showing the current position. In addition there were other cameras which showed various views of the players and the board. You could read the clock times on some of them. These views sometimes were briefly substituted for the board position on the TV monitors. The result was that you could follow the moves in the lobby, the cafeteria, and the hall at all times, but the clock times were readable only every few moves.

To record the times I used a small 24-game scorebook, which I bought at the hall. The small pamphlet sold for 100 Icelandic Kronur, which was a bit more than one US dollar, at the match. It had the word “Skak” on the cover, which is the Icelandic word for chess.

When the TV did show the clock, I could compute, by totaling the two times, the time of the start of the match. After that, when a player moved, I could figure the total game time from my watch, subtract the time of the opponent, and the difference would be the time of the player who just moved. Then, when the opponent moved a few minutes later, I would repeat the procedure using his opponent’s time, as recorded in my notebook.

When the TV showed the chess clock the next time, I could correct, if necessary, my notes for times taken by the player who was not on the move. After about six moves without seeing the clock, my time for a player might be one minute off, since I did not record minutes and seconds.

If I was one minute too short for a player, and it was six moves since the previous correction, I would add one minute to the three most recent time entries and leave the other three entries alone. In game three, however, I came upon an error, early in the game, of nine minutes for Fischer’s time:

After Spassky’s 8th move, I started to jot down the times, having seen Spassky’s clock on the closed circuit TV. After Fischer’s 18th move, while Spassky was thinking, the TV showed 1:07 on Fischer’s clock, according to my notes. Although my time for Spassky was OK, I was somehow short by 9 minutes on Fischer’s time, which I had recorded as 0:58.

I could not figure out how my 9-minute error occurred, until October 31st, 2008, when I read the excellent posting at Chess Base By Prof. Christian Hesse. It explained that the arbiter had actually started the clock on time and Spassky had immediately played 1.d4. And it was not until 5:09, nine minutes later, that Fischer played his reply, 1... Nf6.

In the hall, we were looking at a stage with nobody there, but watching on the closed circuit TV. I don’t remember seeing anything on the closed circuit TV until just before Fischer sat down, so I assumed the game started late. I probably saw Spassky’s clock time and calculated Fischer’s clock time using my mistaken start time. That is, until I could actually see Fischer’s clock on the TV after his 18th, and saw that my time for Fischer was 9 minutes too short.

Using Prof. Hesse’s information, I have assumed that my mistaken start time was the cause of my 9-minute error, and that the error was made for moves 8-18. In these notes, I have corrected Fischer’s times for these moves. The times for move one are according to the ChessBase article.

Here are the times for games three to five, as recorded by Lawrence Stevens in Reykjavik:

| Game 3, July 16-17, 1972

Spassky Fischer |

Game 4, July 18th, 1972

Fischer Spassky |

Game 5, July 20th, 1972

Spassky Fischer |

The above times were published on the web site The Crack Team, which is a place for a group of friends to make anonymous postings, serious, humorous, or a combination of both, about any topic. More about the contributions to chess and the Reykjavik match in our next installment.

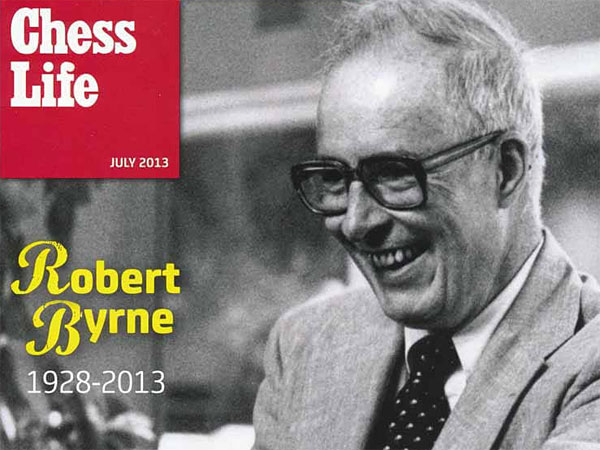

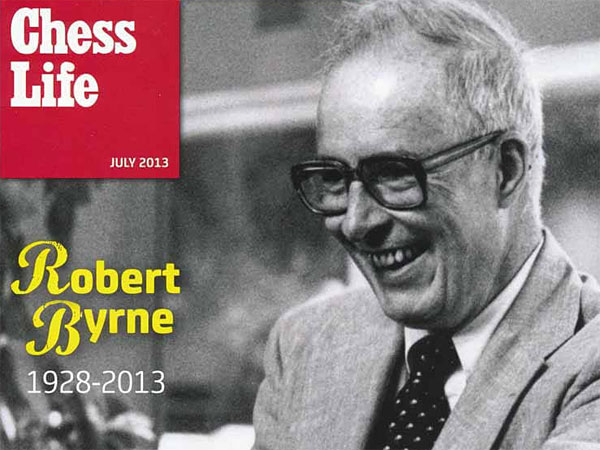

Now to the games in the Spassky-Fischer match. The September issue of Chess Life & Review had a report by GM Robert Byrne, who was on site in Reykjavik and annotated games four and five (as well as games one and three).

GM Robert Byrne, (April 20, 1928 – April 12, 2013), was US Champion in 1972, World Championship Candidate in 1974, nine times member of the US Olympiad team (from 1952 to 1976), university professor and New York Times chess columnist (from 1972 to 2006).

Robert was a good friend whom I (Frederic Friedel) met on a number of occasions. I especially remember a visit to his home in Ossining, New York, where we had dinner and then, over glasses of wine, he spent hours telling me about his 1972 stay in Reykjavik. He showed me games on a chessboard and described what he had experienced at the time. I also got his book on the match, with a nice dedication. Years earlier, in the September 1972 issue of Chess Life & Review he had written:

Spassky got off a surprise Sicilian in the fourth game, for which his analysis team had prepared him well. A brilliant pawn sacrifice at the 16th move gave him a raging attack, but he still could not find a decisive way through the challenger's trenchant defense. The game is still the subject of continuing debate here, no one yet having found a clear conclusion as to what the result should have been. After the players agreed to a draw, the score was 2½-1½ with Spassky still leading.

The following annotations by Robert Byrne appeared on pages 539-540 of the magazine (the pages of CL&R were numbered through for the entire year). They were in English Descriptive Notation, which is not completely trivial to interpret (even if like me you started off with this form of chess moves). For instance a move like RxP is bewildering if the rook can take two pawns. You need to look carefully to recognize that in one case it takes with check, and since this is not given (as RxPch) it has to be the other pawn. It was fun to read and enter these moves. I have kept the orthography from that time, e.g. the capitalizing of all piece names, but translated moves in the text to modern algebraic.

[Event "Reykjavik, World Championship"] [Site "Reykjavik"] [Date "1972.07.18"] [Round "4"] [White "Fischer, Robert James"] [Black "Spassky, Boris Vasilievich"] [Result "1/2-1/2"] [ECO "B88"] [WhiteElo "2785"] [BlackElo "2660"] [Annotator "Byrne,Robert"] [PlyCount "89"] [EventDate "1972.07.11"] [EventType "match"] [EventRounds "21"] [EventCountry "ISL"] [SourceTitle "MainBase"] [Source "ChessBase"] [SourceDate "1999.07.01"] 1. e4 c5 {Using Bobby's own favourite weapon against him comes as a terrific surprise.} 2. Nf3 d6 3. d4 cxd4 4. Nxd4 Nf6 5. Nc3 Nc6 6. Bc4 e6 7. Bb3 Be7 8. Be3 O-O 9. O-O a6 10. f4 Nxd4 11. Bxd4 b5 12. a3 Bb7 13. Qd3 a5 $1 {As Spassky demonstrated in this game, the pawn sacrifice involved here is much stronger than its reputation. It must be accepted, for otherwise ...b4 gives Black too good a position.} 14. e5 dxe5 15. fxe5 Nd7 16. Nxb5 (16. Ne4 Bxe4 17. Qxe4 Nc5 18. Bxc5 Bxc5+ 19. Kh1 Qd4 $1 $15 {Purdy}) (16. Qxb5 $2 Ba6) 16... Nc5 17. Bxc5 ({Giving Black the two Bishops is not a happy choice, but} 17. Qe3 Nxb3 18. Qxb3 (18. cxb3 $4 Qd5 $19 {[%cal Rd5g2,Rd5b5]} 19. Qe2 Ba6 {wins a piece.}) 18... a4 19. Qd3 Ba6 20. Rad1 Qa5 21. c4 Bxb5 22. cxb5 Rab8 23. b6 {only results in Black's obtaining a better pawn position.}) 17... Bxc5+ 18. Kh1 Qg5 (18... Qxd3 {is now in White's favor after} 19. cxd3 Ba6 20. Nc7 Bxd3 21. Rfc1 $1 $16 Rab8 22. Nxe6 $1) 19. Qe2 (19. Qg3 {is safer but gives nothing after} Qxg3 20. hxg3 Ba6 21. Bc4 (21. a4 Bxb5 22. axb5 Bd4 23. c3 Bxe5 24. g4 Rfd8 25. Rfd1 Bc7 {=/+ Smyslov}) 21... Bxb5 22. Bxb5 Bd4 23. c3 Bxe5 $15 {Bobby courageously tries to refute Spassky's gambit and spends the rest of the game suffering for his unwise decision.}) 19... Rad8 20. Rad1 Rxd1 21. Rxd1 h5 $1 { This little unit threatens to travel to h3, shredding the last of the White defenses.} 22. Nd6 Ba8 23. Bc4 h4 24. h3 {The only defense. However, the squares in the vicinity of the White King are now pitifully weak.} (24. Bd3 h3 25. Be4 Qxe5 26. Bh7+ Kxh7 27. Qxe5 hxg2# {is mate.}) 24... Be3 25. Qg4 { What else can White do?} ({Black was treatening} 25. -- Qg3 {[%cal Rg3h3,Re3f4] followed by ...Qxh3 mate; as well as ...Bf5 to seize the pawn on e5.}) 25... Qxe5 (25... Qxg4 26. hxg4 h3 27. Bf1 f6 28. Nc4 {is nothing for Fischer to worry about.}) 26. Qxh4 g5 27. Qg4 {[%cal Rg4g3,Rg4d1] It is necessary to keep both the g3 square and the Rook defended.} Bc5 ({To reply} 27... f5 {is impossible for} 28. Qh5 {threatens perpetual check, and} Kg7 $2 {loses after} 29. Ne8+ Kg8 (29... Rxe8 30. Rd7+ {and mates}) 30. Qg6+ Kh8 31. Qh6+ Kg8 32. Bxe6+ Rf7 33. Nf6+ {with mate to follow.}) ({There is no win after} 27... Rd8 { since} 28. Nxf7 Rxd1+ 29. Qxd1 Kxf7 ({Nor is} 29... Qg3 {good for anything more that a draw, since} 30. Nh6+ $1 Kg7 31. Qd7+ {leads to perpetual check. [Editorial comment: actually it leads to mate:} Kh8 32. Qd8+ Kg7 33. Qg8+ Kxh6 34. Qxe6+ Kh5 35. Qe8+ Kh6 36. Qf8+ Kg6 37. Bd3+ Be4 38. Bxe4+ Kh5 39. Qh8# { You can analyse in the JavaScript player, which Byrne did not have at the time. ]}) 30. Qd7+ Kf6 31. Qd8+ {[%cal Rd8a8] recovers the Bishop. It is amazing that Fischer is still alive here.}) 28. Nb5 Kg7 {[%cal Rf8h8,Rh8h4] Spassky menaces the crushing R-h8-h4.} 29. Nd4 {[#]} Rh8 ({Gligoric and Olafsson maintained that Black can win here by} 29... Rd8 {since} 30. Nxe6+ ({On} 30. Nf5+ {which would be a good answer to 29...Bd6} Kf6 31. Nh6 Rxd1+ 32. Qxd1 Kg6 33. Ng4 Qxb2 {Black has an overwhelming position.}) ({But the situation is not clear after} 30. c3 {If} Bd6 ({If} 30... Rh8 31. Nf3 ({But here} 31. Rf1 $1 Rh4 (31... Bd6 32. Nf5+ {at least draws by perpetual check.}) 32. Nf5+ $1 Qxf5 33. Rxf5 Rxg4 34. Rxc5 Rxg2 35. Rxa5 Bf3 36. Bf1 {is still perhaps tenable.}) 31... Bxf3 32. Qxf3 Bd6 33. Kg1 Rh4 {wins for Black.}) 31. Kg1 Rh8 32. Nf5+ $1 exf5 33. Qxg5+ Kf8 34. Qd8+ {White draws.}) 30... fxe6 31. Rxd8 Qe1+ {is mate in three.}) 30. Nf3 Bxf3 31. Qxf3 Bd6 32. Qc3 {At last Bobby can catch his breath, now that the shooting is over.} Qxc3 33. bxc3 Be5 34. Rd7 Kf6 35. Kg1 Bxc3 36. Be2 Be5 37. Kf1 Rc8 38. Bh5 {By forcing the exchange of Rooks, this move eliminates even the minute chance of Black's exploiting the fragmented pawn position and makes the game an obvious draw.} Rc7 39. Rxc7 Bxc7 40. a4 Ke7 41. Ke2 f5 42. Kd3 Be5 43. c4 Kd6 44. Bf7 Bg3 45. c5+ 1/2-1/2

On game five Robert Byrne wrote (CL&R Sept. 1972, p. 537):

In the fifth game, Bobby again chose the Nimzo-Indian, varying with Huebner's 6...BxNch, which dogmatically offers chances to both sides. Once again, as in the third contest, an unexpected and unusual Knight move at Fischer's 11th turn brought down Spassky's ambitious attempt to seize the initiative. Spassky was slowly being pushed back on the defensive, but no immediate win was in sight when the champion blundered under the pressure at his 27th move. Fischer hit him with instant crunch, leveling the match at 2½-2½.

[Event "Reykjavik World Championship"] [Site "Reykjavik"] [Date "1972.07.20"] [Round "5"] [White "Spassky, Boris Vasilievich"] [Black "Fischer, Robert James"] [Result "0-1"] [ECO "E41"] [WhiteElo "2660"] [BlackElo "2785"] [Annotator "Byrne,Robert"] [PlyCount "54"] [EventDate "1972.07.11"] [EventType "match"] [EventRounds "21"] [EventCountry "ISL"] [SourceTitle "MainBase"] [Source "ChessBase"] [SourceDate "1999.07.01"] 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. Nf3 c5 5. e3 Nc6 6. Bd3 Bxc3+ {West German Grandmaster Robert Huebner's dogmatic variation gives White doubled pawns without even waiting for a2-a3. The point is to take advantage of the placement of White's Knight at f3, where it is considerably weaker than at e2. Huebner's recipe also calls for 0-0-0, although the placement of Black King cannot be determined until White reveals what formation he will set up. Recent games have consistently demonstrated the strength of Huebner's plan.} 7. bxc3 d6 8. e4 ({An alternative is to keep the King Bishop's diagonal open by} 8. Nd2 {but after} e5 {it is not apparent how White is to obtain the initiative.}) 8... e5 9. d5 Ne7 {Huebner's idea is to use the Black minor pieces for maneuvering on the Kingside.} ({In any case} 9... Na5 {would be a mistake since } 10. Nd2 {[%cal Gd2b3] followed by N-b3 virtually compels ...NxN, mending the White pawn position after PxN.}) 10. Nh4 h6 {[#]} 11. f4 ({Two alternate tries here are} 11. g3 Bh3 12. Rg1 g5 13. Ng2) ({and} 11. f3 g5 12. Nf5 Nxf5 13. exf5 Nh5 {Neither one has worked out satisfactorily for White.}) 11... Ng6 $1 { This wierd reply stops White cold.} ({The text move 11.f4 appears to be tremendous, since} 11... exf4 12. Bxf4 g5 $2 13. e5 $1 Nd7 14. e6 $1 gxf4 15. exd7+ Qxd7 16. O-O {yields White an overwhelming position.}) 12. Nxg6 (12. Nf5 $2 Bxf5 13. exf5 Nxf4 14. Bxf4 exf4 15. O-O O-O 16. Rxf4 {recovers the pawn, but at the expense of a winning position for Black, who has a good Knight against a bad Bishop and control of the King file.}) (12. fxe5 $2 {is even worse after} Nxh4 13. exf6 Qxf6 {leaving White in a disorganized mess.}) 12... fxg6 13. fxe5 dxe5 14. Be3 {A first glance might give the impression that White stands well here, with the two Bishops and a protected passed pawn. But the KB [the Bd3] has the purely passive role of guarding the KP and QBP [d4 and c4], while the pawn formation on the Kingside is such that White is denied his normal attacking chances there. It is Black, with his maneuvering possibilites against the fixed enemy pawn weaknesses, who has the upper hand.} b6 15. O-O O-O 16. a4 a5 {There was not possibility of avoiding this, since a5 would have followed, giving White two Queenside files to play on. Black's backward QNP [Pb6] is a drawback, but not a serious one because White's pressure against it is limited by his lack of mobility.} 17. Rb1 Bd7 18. Rb2 Rb8 19. Rbf2 {This is a nothing move, but it is not clear how White can proceed in any event. In order to scare up real threat again the QNP [Pb6] White must be able to triple the QN [b] file. This would require a long-winded maneuver beginning with Qa1, which would give Black a chance to attack on the other wing. If Black was really worried about anything after 19.Qa1 he could always get rid of a pair of Rooks by ...Ng4.} Qe7 20. Bc2 g5 21. Bd2 Qe8 22. Be1 Qg6 23. Qd3 Nh5 24. Rxf8+ Rxf8 25. Rxf8+ Kxf8 26. Bd1 Nf4 {[#]Now Black's advantage is glaringy obvious, but is it enough to win by force? Grandmaster Fridrik Olafsson thinks so, but I am not sure.} 27. Qc2 $4 ({After} 27. Qb1 { [%cal Gf8e7,Ge7d8,Gd8c8,Gh6h5,Gh5h4,Gg6h6,Gg5g4] (best) Black can continue by . ..Ke7-d8-c8 and then start a Kingside attack by ...h5-h4, ...Qh6 and ...g4. It is difficult to suggest counter-measures and, unfortunately, we are deprived of see the thing worked out, because Boris makes his biggest blunder in the match right here.}) 27... Bxa4 $1 (27... Bxa4 {The sacrifice cannot be accepted, for} 28. Qxa4 $2 ({Declining is also hopeless, because} 28. Qb1 Bxd1 29. Qxd1 Qxe4 {leave White two pawns down to begin with and the prospect of losing more staring him in the face.}) 28... Qxe4 {threatens two mates at once, and} 29. Kf2 Nd3+ 30. Kg3 Qh4+ 31. Kf3 Qf4+ 32. Ke2 Nc1# {is mate.}) 0-1

Byrne wrote:

To overcome a two-point deficit against the world champion in only three games is fantastic. But Fischer's play is too sharp for Boris. Fischer's do-it-yourself opening analysis has been vastly superior to what the entire army of Soviet analysts could give Boris. The one time the Russian had a success in the opening, in the fourth game, Fischer's remarkable defensive middle game play denied him the point. When Bobby gets going, the colors do not matter. Spassky will not be able to hang on in this match unless he can find some way of defending against Fischer's defenses. Despite the first two minus points, I am still sticking to my earlier prediction on 12½-8½ for Fischer.

For this dramatic game we also have annotations by IM Sagar Shah, who has been helping us document the match. You can replay them and compare his notes to those above.

[Event "Reykjavik World Championship"] [Site "Reykjavik"] [Date "1972.07.20"] [Round "5"] [White "Spassky, Boris V"] [Black "Fischer, Robert James"] [Result "0-1"] [ECO "E41"] [WhiteElo "2660"] [BlackElo "2785"] [Annotator "Sagar Shah"] [PlyCount "54"] [EventDate "1972.07.11"] [EventType "match"] [EventRounds "21"] [EventCountry "ISL"] [SourceTitle "MainBase"] [Source "ChessBase"] [SourceDate "1999.07.01"] {This was the fifth game of the match and Fischer was trailing with a score of 2.5:1.5. He equalises the match with a win over here. But more than the victory it is simply amazing to see him break many positional rules and yet come out on the top.} 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 Bb4 4. Nf3 c5 5. e3 Nc6 6. Bd3 Bxc3+ $5 {The Heubner Wall which is one of the most fascinating positions in the Nimzo Indian.} 7. bxc3 d6 {Black gives up his bishop voluntarily and then sets up the pawns on the dark squares so that the other bishop can become more active.} 8. e4 (8. O-O e5 9. Nd2 {is the other way to play, keeping the centre flexible. But Spassky chooses the most natural plan of seizing the center.}) 8... e5 9. d5 Ne7 {The position is closed and in such situations, the knights are often better than the bishops. Especially the bishop on d3 is not at all a great piece. But Spassky has the idea of moving his knight to h4 and following it up with f2-f4 in order to open the position.} (9... Na5 {Usually the knight is well placed here in the Nimzo Indian because it can put pressure on the c4 pawn. But in this particular case White can execute a strong idea starting with } 10. Nd2 $1 O-O 11. O-O (11. Nb3 b5 {might lead to unclear consequences.}) 11... b6 12. Nb3 $14 {The knigh on a5 cannot maintain itself on that square.}) 10. Nh4 h6 11. f4 {This was the first time that this move was played by anyone and it was pretty natural.} (11. O-O g5 12. Nf5 (12. Qf3 Nfg8 13. Nf5 Nxf5 14. exf5 Nf6 15. h4 g4 16. Qg3 Kd7 17. f3 gxf3 18. Qxf3 Kc7 19. Be2 Qg8 20. Kf2 h5 21. Ke1 Bd7 22. Bg5 Ng4 23. Qe4 f6 24. Bd2 Nh2 25. Kf2 Qh7 26. Kg1 Nxf1 27. Rxf1 Rag8 28. Kh2 Rg7 {0-1 (28) Meskovs,N (2441)-Kovalenko,I (2650) Riga 2014}) 12... Nxf5 13. exf5 e4 14. Re1 Bxf5 15. f3 Bg6 16. fxe4 Nd7 $15 {[%cal Gd7e5] Black has the perfect blockade.}) 11... Ng6 $1 {What a brilliant concept by Fischer. When faced with a new idea he responds in the best possible manner. The point is that White cannot play Nf5 as after Bxf5 exf5, the f4 pawn will be hanging.} (11... exf4 12. Bxf4 g5 13. e5 Ng4 14. e6 $1 Nf6 15. O-O gxf4 16. Rxf4 $18) (11... Bg4 12. Qd2 exf4 13. Qxf4 $14) 12. Nxg6 fxg6 13. fxe5 (13. O-O {Spassky-Fischer 5 was the pioneering game in this line. Later people started to push forward instead of taking on e5.} O-O 14. f5 {And Black has a wonderful flank strike to break White's center.} b5 $1 15. cxb5 c4 $1 16. Bc2 ( 16. Bxc4 $6 Qb6+ 17. Kh1 Nxe4 $15) 16... gxf5 17. exf5 Qb6+ 18. Kh1 Qxb5 $15 { Black has an excellent position as White's center is falling apart.}) 13... dxe5 {Have a look at this position without any prejudices and determine who is better. Of course it should be White don't you agree? 1. He has the bishop pair; 2. a protected passed pawn on d5; 3. Black's e5 pawn is isolated and his g-pawns are doubled. How did Fischer win the game in spite of all these deficiencies in his position? Take a look:} 14. Be3 b6 15. O-O O-O 16. a4 a5 $1 {Another superb move fixing the a4 pawn on the light square. It is true that the b6 pawn is weakened and stands backward on the open file. But Fischer realises the importance of keeping the position closed and not letting White open further lines.} (16... Ne8 17. Rxf8+ Kxf8 18. a5 $16) (16... Ng4 17. Bd2 { The knight has not really gained from going to g4.}) 17. Rb1 Bd7 {White is perfectly developed. What should he do next? It's not at all easy to suggest a good plan for him. The b6 pawn can be attacked, but it would be easily defended. At the same time Black is looking towards exchanging all the rooks in the position. Once that happens the weakness on c4 and a4 as well as e4 will be accentuated, as two black minor pieces would be able to attack them while only one white bishop can defend it.} 18. Rb2 Rb8 19. Rbf2 (19. Bf2 Qe7 20. Bg3 g5 21. Rbf2 Rf7 22. Qb1 Qd6 23. Bc2 Rbf8 24. Bd1 Ne8 $1 {The exchange of rooks is to Black's favour. Even though the computer thinks this position is worse for Black, I disagree. Black has a clear cut plan while White lacks one. Still this is better than the game as White is attacking Black's only weakness in the position that is the pawn on e5.}) 19... Qe7 20. Bc2 g5 $1 { Gaining space and preparing to transfer the queen on the wonderful square on g6.} 21. Bd2 {As you can see Spassky just doesn't understand what is to be done.} Qe8 {Also keeping an eye on the a4 pawn.} 22. Be1 Qg6 23. Qd3 Nh5 24. Rxf8+ Rxf8 25. Rxf8+ Kxf8 26. Bd1 Nf4 27. Qc2 $2 {The game ends abruptly after this.} (27. Qb1 Ke7 {The material is even and the computer assesses this as equal. But nothing can be farther from the truth. Black is just better, maybe even close to winning: I put my king to c7 to defend the b6 pawn. Later I transfer the bishop to a6 and the knight to d6 and tie up all the white pieces. The black queen can then run amok in the white position. True, this will all take some time, but it is impossible to prevent it if Black plays with decent technique.}) 27... Bxa4 (27... Bxa4 28. Qxa4 Qxe4 $19 {[%cal Ge4e1,Ge4g2]}) 0-1

And if you haven't enough of the Match of the Century you may want to check Mega Database, which has extensive commentary of all the games.

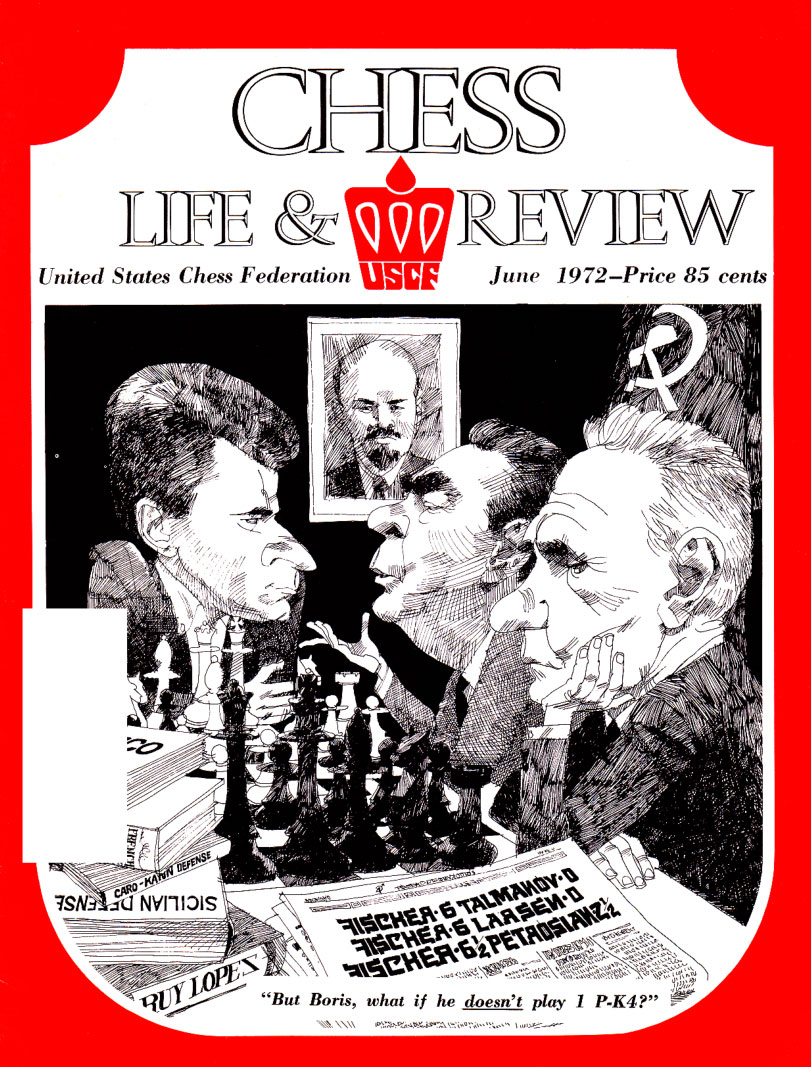

The June 1972 cover of Chess Life & Review (click to enlarge) had a cartoon by Bob Walker, of Boris Spassky consulting with Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin before the match.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (1)

In the final week of June 1972 the chess world was in turmoil. The match between World Champion Boris Spassky and his challenger Bobby Fischer was scheduled to begin, in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, on July 1st. But there was no sign of Fischer. The opening ceremony took place without him, and the first game, scheduled for July 2nd, was postponed. Then finally, in the early hours of July 4th, Fischer arrived. Frederic Friedel narrates.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (2)

The legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer was staged in the Laugardalshöllin in Reykjavik. This is Iceland’s largest sporting arena, seating 5,500, but also the site for concerts – Led Zeppelin, Leonard Cohen and David Bowie all played there. 45 years after the Spassky-Fischer spectacle Frederic Friedel visited Laugardalshöllin and discovered some treasures there.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (3)

On July 11, 1992 the legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer finally began. Fischer arrived late, due to heavy traffic. To everybody's surprise he played a Nimzo instead of his normal Gruenfeld or King's Indian. The game developed along uninspired lines and most experts were predicting a draw. And then, on move twenty-nine, Fischer engaged in one of the most dangerous gambles of his career. "One move, and we hit every front page in the world!" said a blissful organiser.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (4)

7/16/2017 – The challenger, tormented by the cameras installed in the playing hall, traumatically lost the first game of his match against World Champion Boris Spassky. He continued his vigorous protest, and when his demands were not met Fischer did not turn up for game two. He was forfeited and the score was 0-2. Bobby booked a flight back to New York, but practically at the very last moment decided to play game three – in an isolated ping-pong room!