Fischer plays the Alekhine

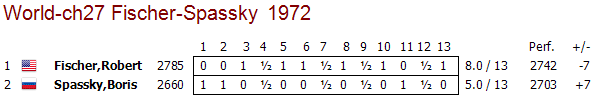

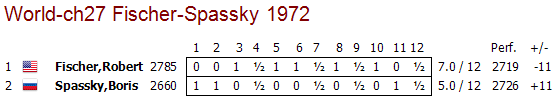

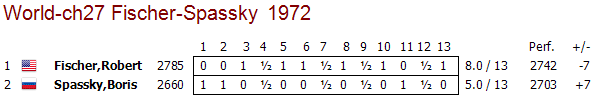

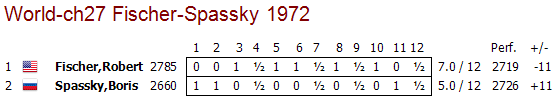

On August 9th 1972, 45 years ago, the score in the Match of the Century was 7.0-5.0 for Bobby Fischer. Boris Spassky had fought back and won the 11th game, making the battle more exciting. The 12th encounter was a comfortable draw for him as Black.

One of the most exciting endgames in Championship history

In the magazine New in Chess vol 6/2012, GM Lubomir Kavalek, who was in Reykjavik for the Match of the Century, both as a journalist and, in the second half, as one of Fischer’s seconds, describes what happened in the next game [we quote with kind permission of the author]:

"Game 13 puzzled many players even after it was finished. It was an epic battle and, according to Mikhail Botvinnik, the patriarch of Soviet chess, Fischer’s greatest achievement in the match. ‘Nothing like this had previously happened in chess,’ Botvinnik said. His former world championship challenger, David Bronstein, played the game over many times and it was an enigma to him. ‘Like a mysterious sphinx, it still teases my imagination,’ he said.

"Game 13 puzzled many players even after it was finished. It was an epic battle and, according to Mikhail Botvinnik, the patriarch of Soviet chess, Fischer’s greatest achievement in the match. ‘Nothing like this had previously happened in chess,’ Botvinnik said. His former world championship challenger, David Bronstein, played the game over many times and it was an enigma to him. ‘Like a mysterious sphinx, it still teases my imagination,’ he said.

It was during this game that I started working with Bobby on the adjournment games after he sent his official second, Bill Lombardy, away from his suite. Bobby and Bill were a great pair, but during that night they turned into two strong personalities with two different opinions. The tension was resolved by Lombardy’s sneeze. ‘I don’t want to get your cold, Bill,’ Bobby said and added he wanted to work with me. Bill left quietly.

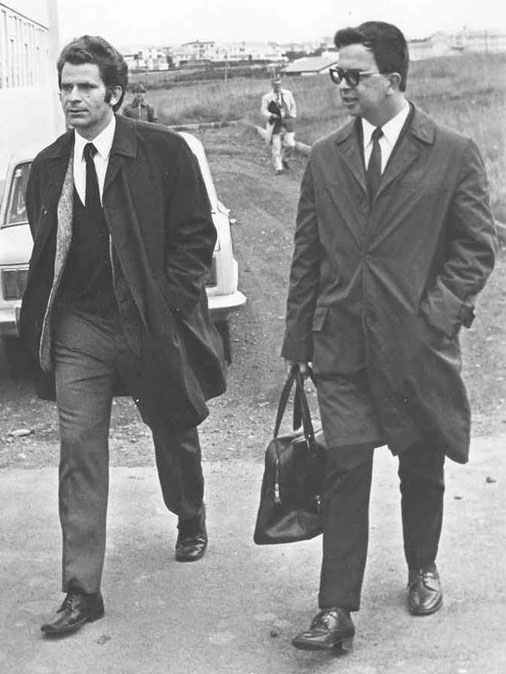

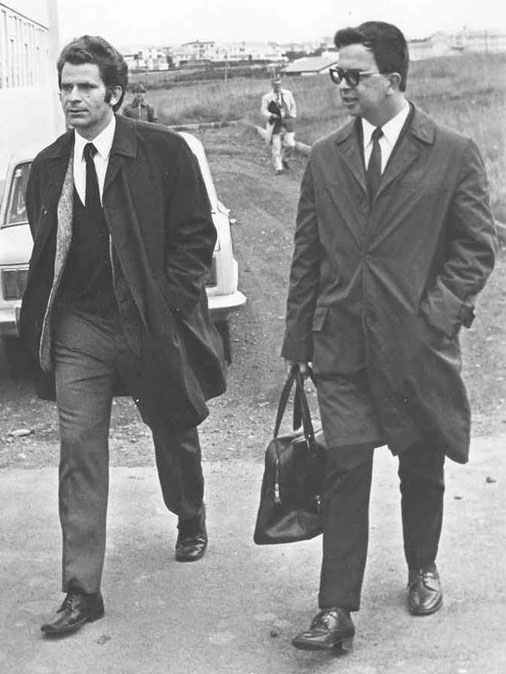

Fischer's second in Reykjavik: the Reverend William Lombardy [photo: Icelandic Chess Federation Skáksamband Íslands]

From that moment on, I analysed just with Bobby till the end of the match. Although we had never worked together before, I had Bobby’s trust. Earlier in the year I had finished first at the U.S. championship, becoming the second highest-rated player in the country after him. As long as he won the world crown it didn’t matter who helped him. It was his choice.

The game had an unlucky number and it had all the drama of a swing game. With a win, Spassky would shrink Bobby’s lead to a single point. Although Bobby had the edge, the adjourned position was a minefield, requiring utmost care. One line emerged as the most practical in our analysis. The play was straightforward, but there were a few roundabouts. We reached the position with Bobby’s rook arrested on g8 by White’s pawn and bishop. Spassky’s rook had to cope with Fischer’s five pawns, but it seemed that Boris would be able to do it. The black king could be cut off from crossing the d-file. Did we hit a snag?

‘Bobby...’ I began. He got the whiff of what I was about to say and intercepted me: ‘Don’t worry,’ he said confidently, ‘I just push the h-pawn and get in with the king. Anyway, we are too far.’ We had already strayed some 20 moves away from the adjourned position and there were many branches and trees of variations we had not covered. So we looked back and checked as much as we could. It was daylight when I went back to my room.

There was one thing I noticed. No matter how deep the analyses, Bobby committed everything to memory. No written notes.

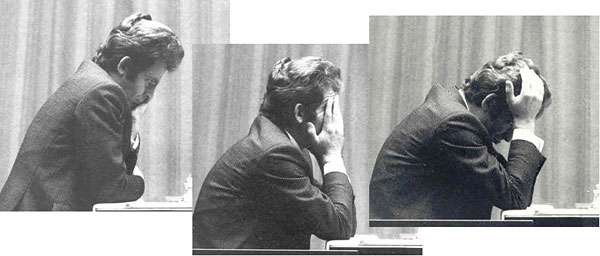

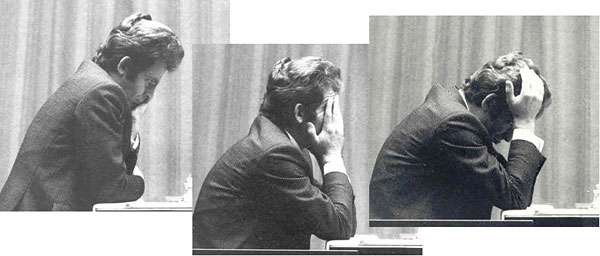

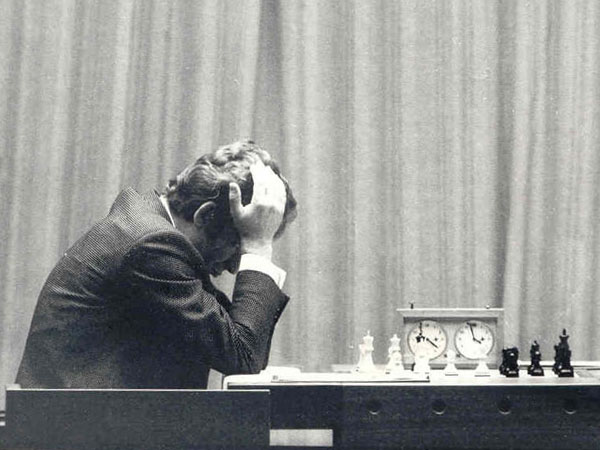

Bobby was 21 minutes late for the adjournment. The game resumed and everything went as we had analysed. Boris imprisoned the black rook on g8 and the moment to sacrifice the h-pawn arrived. It was Bobby’s only chance, but he was not moving. After some 45 minutes everybody was puzzled. What is he looking at? Is there a win? Larsen, having stopped in Iceland on the way to the U.S. Open, was entertaining the crowd in the press room, commenting on the adjournment. He was in danger of missing his flight to New York.

Bent Larsen (right) with Robert Byrne and Frank Brady in Reykjavik 1972 [photo: Icelandic Chess Federation Skáksamband Íslands]

Bobby was still sitting at the board. He had realized that he was going nowhere. The long think somehow affected Spassky’s concentration. Shortly after Bobby sacrificed the pawn, Boris made a few forced moves and blundered. The game went Fischer’s way. He turned Game 13 into a lucky number and was up three points in the match. And Larsen made it to Keflavik airport on time.

Bobby was happy about the win. ‘What’s the idea of chess?’ he laughed. ‘It’s winning, isn’t it.’ The loss was devastating for Spassky and instead of playing the next game, he took a time-out. Fischer didn’t mind, although before the match he had a different idea. ‘Taking time-outs had been misused,’ he said. ‘The Russians did it during their matches. When they decided to get a little rest, almost always after they lost a game, they claimed to be sick. I think one should play, unless you are so sick you can’t physically make it. It’s part of chess to be in good physical condition. If you are not, you can only complain to yourself. I don’t believe in time-outs every time the weather slightly changes.’"

The above picture of Bobby Fischer, Lubomir Kavalek and Florencio Campomanes is from the opening ceremony of the 1973 Manila tournament. Bobby was invited by Filipino President Ferdinand Marcos, made nine moves in ceremonial game with him, collected $20,000 and later flew to Japan (where he met his future wife Miyoko Watai for the first time).

In Garry Kasparov On My Great Predecessors, Part 4 the 13th World Champion described the situation after the first twelve games: the champion had not won since the first game, and of the last eight points had only scored 1½ points – from three draws. Then he "calmed down and began fighting with the desperation of the doomed: he sensationally crushed his opponent in the 11th game."

In Garry Kasparov On My Great Predecessors, Part 4 the 13th World Champion described the situation after the first twelve games: the champion had not won since the first game, and of the last eight points had only scored 1½ points – from three draws. Then he "calmed down and began fighting with the desperation of the doomed: he sensationally crushed his opponent in the 11th game."

After the the confident draw by Spassky in the 12th game "Fischer realised that obstinacy was not a good thing and he decided temporarily to give up the Sicilian. For the first time in the match he employed the Alekhine Defence, which was another unpleasant surprise for Spassky.

'I will say frankly: no serious analysis of the variations for White in this opening had been made. This happened, because a number of experts, including Spassky himself, were convinced that Fischer was extremely constant in his opening tastes and that against 1 e4 he was unlikely to play anything except the Sicilian Defence.' (Krogius)"

Nikolai Krogius (right), assistant to Boris Spassky in his World Championship matches against Petrosian in 1969, and Fischer in 1972 [photo: Skáksamband Íslands]

In the November 1972 issue of Chess Life & Review, which today has become the official magazine of the US Chess Federation Chess Life, GM Robert Byrne reporting from Reykjavik, wrote:

Game 13 was a rousing battle. Fischer sprang a surprise Alekhine Defense, rapidly seizing the initiative and snatching a pawn. Since Spassky did not like the looks of the position he would be forced into if he played to retake the pawn, he sacrificed it permanently going all out for a Kingside attack. An inaccuracy by Fischer fueled the onslaught to alarming proportions but at the crucial point the champion vacillated, drifting into a pawn-down endgame.

That might, perhaps, have been the end of the story, except that Bobby took matters too lightly and blew the win a few moves before adjournment. When the game was resumed he put an incredible effort into the endgame, sacrificing a Bishop, allowing his Rook to be imprisoned and, in effect, going for a win with King and five pawns against King and Rook. Spassky's draw was there but he was worn down after so many hours of play—he blundered' at the 69th move and lost.

In the following commentary, as in his game summaries above, we retain the descriptive notation that Byrne (like everyone in the English world at the time) was wont to use. It is good practice to follow his remarks in this archaic form – to get you started translations are provided for the first ten moves. I urge you to replay the entire game carefully – maximize the board, start an engine and enjoy the moves. And learn from them. I certainly did so myself, in the hours I spent transcribing Byrne's wonderfully lucid annotations.

| Replay and check the LiveBook here |

Please, wait...

1.e4 Nf6 2.e5 Nd5 3.d4 d6 4.Nf3 4.c4 Nb6 5.f4 4...g6 5.Bc4 Nb6 6.Bb3 Bg7 7.Nbd2 7.Ng5 0-0 7...d5 8.f4 e6 9.Nf3 0-0 8.e6 7...0-0 8.h3?! a5 9.a4?! dxe5 10.dxe5 Na6 11.0-0 Nc5 12.Qe2 Qe8 13.Ne4 13.Qb5 Qxb5 14.axb5 Bf5! 13...Nbxa4 14.Bxa4 Nxa4 15.Re1 15.Qc4 Bd7 16.Qxc7 Qc8 17.Qxc8 Rfxc8 15...Nb6 16.Bd2 a4 17.Bg5 h6 18.Bh4 Bf5?! 18...Be6 18...Ra5!? 19.g4 Be6 19...Bxe4 20.Qxe4 Rb8 21.Qb4! g5 22.Bg3 e6 23.h4 20.Nd4 Bc4 21.Qd2 Qd7 21...Bxe5 22.Qxh6 Bg7 22...Bxd4 23.Ng5 23.Qd2 Qd8 24.c3 f6 25.f4 22.Rad1 Rfe8 23.f4 Bd5 24.Nc5 Qc8 25.Qc3? 25.e6 Nc4 26.Qe2! Nxb2 27.Nf5‼ Nxd1 27...Bc4! 28.exf7+ Kxf7 29.Qxe7+! Rxe7 30.Rxe7+ Kf8 31.Nd7+! Qxd7 31...Kg8?? 32.Rxg7+ Kh8 33.Bf6 gxf5 34.Ne5! Qe8 35.Rdd7 32.Rdxd7 Bc3‼ 33.Nxh6 a3 34.Rf7+ Bxf7 35.Rxf7+ Ke8 36.Re7+ Kf8 28.Nxg7 Kxg7 29.Qe5+ f6 30.Qxd5 Nb2 31.g5! 25...e6 26.Kh2 Nd7 27.Nd3 27.Nb5 Nxc5 28.Qxc5 Ra5 29.c4 Bc6 30.Qb4 b6 27...c5 28.Nb5 Qc6 29.Nd6 29.Na3 b5 29...Qxd6 30.exd6 Bxc3 31.bxc3 f6 32.g5 hxg5?! 32...c4 33.Nb4 hxg5 34.fxg5 f5 35.Nxd5 33.fxg5 f5 34.Bg3 Kf7 35.Ne5+ Nxe5 36.Bxe5 b5 37.Rf1! Rh8? 37...Rg8 38.Rf4 Ke8 39.Rh4 Ra7 38.Bf6! a3 39.Rf4 a2 40.c4! 40.d7? a1Q 41.Rxa1 Rxa1 42.Bxh8 Ke7 43.Rh4 43.c4 Rh1+ 44.Kg3 Rg1+ 45.Kf2 Rg2+ 46.Ke1 bxc4 43...Kxd7 44.Kg3 44.Rh6?? f4 44...Kd6 45.Rh6 Be4 46.Rxg6?? f4+ 40.Ra1? e5! 41.Bxe5 Rhe8 42.Bf6 Re2+ 43.Kg1 Ke6 40...Bxc4 41.d7 Bd5 42.Kg3! Ra3+! 43.c3 43.Kf2 Raxh3 44.d8Q Rxd8 45.Bxd8 e5 46.Bf6 Ke6 47.Re1 a1Q 48.Rxa1 exf4 43.Rd3 a1Q 43...Rha8 43...a1Q 44.Rxa1 Rxa1 45.Rh4‼ Raa8 45...Rg1+ 46.Kf2 Rg2+ 47.Kf1 Rxh4 48.d8Q Rf4+ 49.Ke1 Re4+ 50.Kf1 50.Kd1?? Bb3+ 46.Bxh8 Rd8 47.Bf6 Rxd7 48.Rh7+ Ke8 49.Rh8+ 44.Rh4 e5‼ 45.Rh7+ Ke6 46.Re7+ Kd6 47.Rxe5 Rxc3+! 47...a1Q 48.Rexd5+ Kc6 49.Rxa1 48.Kf2 48.Kh4?? Ra4+ 48...Rc2+ 49.Ke1 Kxd7 50.Rexd5+ Kc6 51.Rd6+ Kb7 52.Rd7+ Ka6 53.R7d2 Rxd2 54.Kxd2 b4 55.h4! Kb5 56.h5 c4 57.Ra1 57.h6 c3+ 58.Kd3 a1Q 59.Rxa1 Rxa1 60.h7 Rd1+! 61.Kc2 Rh1 62.h8Q Rxh8 63.Bxh8 Kc4 57...gxh5 58.g6 h4! 59.g7 59.Bxh4 Rg8 59...h3 60.Be7 Rg8 61.Bf8 61.Bf6 h2 62.Kc1 f4 63.Kb2 c3+ 64.Kxa2 Ra8+ 65.Kb3 Rxa1 66.g8Q Rb1+ 67.Kc2 Rb2+ 68.Kd3 Rd2+ 69.Ke4 h1Q+ 61...h2 62.Kc2 Kc6 63.Rd1! b3+ 64.Kc3?! 64.Kb2 h1Q 65.Rxh1 Kd5 66.Rd1+ Ke4 67.Rc1 Kd3 68.Rd1+ Ke2 69.Rc1 f4 70.Rxc4 f3 71.Rc1 f2 72.Kxb3 f1Q 73.Rxf1 Kxf1 74.Kxa2 64...h1Q! 65.Rxh1 Kd5 66.Kb2 f4 67.Rd1+ 67.Rh8 c3+ 68.Ka1 f3 69.Rxg8 f2 67...Ke4 68.Rc1 Kd3 69.Rd1+?? 69.Rc3+ Kd4 70.Rf3 c3+ 71.Ka1 71.Rxc3‼ a1Q+ 71...c2 72.Rxf4+! Kc3 73.Rf3+! 73.Bb4+ Kd3 74.Ba3 Rxg7 75.Rf3+ Kc4 76.Rf4+ Kd5 77.Rf1 Rd7! 78.Bc1 Ke6‼ 79.Kb2 Rd1 73...Kd2 73...Kc4 74.Rf1 74.Ba3 69...Ke2 70.Rc1 f3 71.Bc5 71.Rxc4 f2 72.Rc1 f1Q 73.Rxf1 Kxf1 71...Rxg7 72.Rxc4 Rd7! 73.Re4+ Kf1 74.Bd4 f2 74...f2 75.Rf4 Rxd4 76.Rxd4 Ke2 0–1 - Start an analysis engine:

- Try maximizing the board:

- Use the four cursor keys to replay the game. Make moves to analyse yourself.

- Press Ctrl-B to rotate the board.

- Drag the split bars between window panes.

- Download&Clip PGN/GIF/FEN/QR Codes. Share the game.

- Games viewed here will automatically be stored in your cloud clipboard (if you are logged in). Use the cloud clipboard also in ChessBase.

- Create an account to access the games cloud.

| Spassky,B | 2660 | Fischer,R | 2785 | 0–1 | 1972 | B04 | Reykjavik World Championship (13) | 13 |

Please, wait...

On August 11th 1972, exactly 45 years ago, the 13th game adjournament session ended and Fischer had restored his three-point lead.

Move times and adjournments

Here are the times for games thirteen, as recorded by Lawrence Stevens, who visited the match in Reykjavik and jotted them down from the video screens:

|

Game 13, August 10-11, 1972

Spassky Fischer

White Black

(ar) (-0:02) (ar) (0:06)

1. e4 (0:00) Nf6 (0:07)

(Spassky left when he made his move and returned 2 minutes after Fischer made his move)

2. e5 (0:02) Nd5 (0:07)

3. d4 (0:02) d6 (0:07)

4. Nf3 (0:03) g6 (0:08)

5. Bc4 (0:05) Nb6 (0:08)

6. Bb3 (0:06) Bg7 (0:08)

7. Nbd2 (0:23) 0-0 (0:14)

8. h3 (0:25) a5 (0:22)

9. a4 (0:33) dxe5 (0:25)

10. dxe5 (0:33) Na6 (0:26)

11. 0-0 (0:47) Nc5 (0:35)

12. Qe2 (0:50) Qe8 (0:51)

13. Ne4 (0:58) Nbxa4 (0:54)

14. Bxa4 (1:04) Nxa4 (0:56)

15. Re1 (1:08) Nb6 (0:58)

16. Bd2 (1:12) a4 (0:59)

17. Bg5 (1:14) h6 (1:06)

18. Bh4 (1:26) Bf5 (1:16)

19. g4 (1:29) Be6 (1:16)

20. Nd4 (1:31) Bc4 (1:17)

21. Qd2 (1:35) Qd7 (1:19)

22. Rad1 (1:37) Rfe8 (1:23)

23. f4 (1:38) Bd5 (1:30)

24. Nc5 (1:40) Qc8 (1:31)

25. Qc3 (1:51) e6 (1:38)

26. Kh2 (1:57) Nd7 (1:40)

27. Nd3 (2:00) c5 (1:41)

28. Nb5 (2:00) Qc6 (1:42)

29. Nd6 (2:04) Qxd6

30. exd6 Bxc3 (1:42)

31. bxc3 (2:04) f6 (1:46)

32. g5 (2:05) hxg5 (1:47)

33. fxg5 (2:05) f5 (1:47)

34. Bg3 (2:06) Kf7 (1:50)

35. Ne5+ (2:07) Nxe5 (1:50)

36. Bxe5 (2:07) b5 (1:56)

37. Rf1 (2:08) Rh8 (2:02)

38. Bf6 (2:12) a3 (2:04)

39. Rf4 (2:22) a2 (2:08)

40. c4 (2:27) Bxc4 (2:09)

41. d7 (2:36) Bd5 (2:16)

42. Kg3(s) (3:08) |

(Fischer was 25 minutes late for the second session. This was a 4 hour Friday adjournment session which started at 2:30 PM. The next two time controls were at move 56 with 3:30 and move 72 with 4:30)

(ar) (2:41)

42. ... Ra3+ (2:42)

43. c3 (3:08) Rha8 (2:42)

44. Rh4 (3:10) e5 (2:42)

45. Rh7+ (3:11) Ke6 (2:42)

46. Re7+ Kd6

47. Rxe5 (3:12) Rxc3+

48. Kf2 (3:13) Rc2+

49. Ke1 (3:13) Kxd7

50. Rexd5+ (3:14) Kc6

51. Rd6+ (3:16) Kb7 (2:43)

52. Rd7+ (3:20) Ka6 (2:44)

53. R7d2 (3:23) Rxd2

54. Kxd2 (3:25) b4

55. h4 (3:26) Kb5

56. h5 (3:26) c4 (2:45)

57. Ra1 (3:37) gxh5 (2:48)

58. g6 (3:39) h4 (2:49)

59. g7 (3:50) h3 (2:50)

60. Be7 (4:08) Rg8 (3:11)

61. Bf8 (4:11) h2 (3:49)

62. Kc2 (4:11) Kc6 (3:51)

63. Rd1 (4:13) b3+ (3:57)

64. Kc3 (4:15) h1Q (4:02)

65. Rxh1 (4:15) Kd5 (4:02)

66. Kb2 (4:18) f4 (4:03)

67. Rd1+ (4:19) Ke4 (4:05)

68. Rc1 (4:23) Kd3 (4:06)

69. Rd1+ (4:26) Ke2 (4:07)

70. Rc1 (4:27) f3 (4:08)

71. Bc5 (4:27) Rxg7 (4:11)

72. Rxc4 (4:28) Rd7 (4:14)

73. Re4+ (4:45) Kf1 (4:15)

74. Bd4 (4:49) f2

0-1

(ar) indicates the player’s arrival.

(s) indicates a sealed move. |

Although Fischer was 25 minutes late for the second session, he still had 45 extra minutes to use at the second time control on move 56. Fischer took 38 minutes for his 61st move, which was the longest of the match for him. And he had spent 21 minutes on the previous move that allowed his Rook to be imprisoned. He had played the first 18 moves of the adjournment quite rapidly, until Spassky’s 60. Be7.

The four-hour playing session had not been exhausted, since Spassky took 32 minutes for his sealed move in the first session, making that session 5 hours 24 minutes long. After he resigned, Spassky immediately analyzed the last few moves at the board, seeing that at move 69, he would have drawn with Rc3 instead of Rd1. He said something to Lothar Schmidt, but he was busy with the official paperwork. Fischer had already left.

This was one amazing game to watch. I could not believe it when Fischer’s Rook was incarcerated on g8 by Spassky’s Bishop and Pawn.

Previous articles

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (1)

In the final week of June 1972 the chess world was in turmoil. The match between World Champion Boris Spassky and his challenger Bobby Fischer was scheduled to begin, in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, on July 1st. But there was no sign of Fischer. The opening ceremony took place without him, and the first game, scheduled for July 2nd, was postponed. Then finally, in the early hours of July 4th, Fischer arrived. Frederic Friedel narrates.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (2)

The legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer was staged in the Laugardalshöllin in Reykjavik. This is Iceland’s largest sporting arena, seating 5,500, but also the site for concerts – Led Zeppelin, Leonard Cohen and David Bowie all played there. 45 years after the Spassky-Fischer spectacle Frederic Friedel visited Laugardalshöllin and discovered some treasures there.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (3)

On July 11, 1992 the legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer finally began. Fischer arrived late, due to heavy traffic. To everybody's surprise he played a Nimzo instead of his normal Gruenfeld or King's Indian. The game developed along uninspired lines and most experts were predicting a draw. And then, on move twenty-nine, Fischer engaged in one of the most dangerous gambles of his career. "One move, and we hit every front page in the world!" said a blissful organiser.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (4)

7/16/2017 – The challenger, tormented by the cameras installed in the playing hall, traumatically lost the first game of his match against World Champion Boris Spassky. He continued his vigorous protest, and when his demands were not met Fischer did not turn up for game two. He was forfeited and the score was 0-2. Bobby booked a flight back to New York, but practically at the very last moment decided to play game three – in an isolated ping-pong room!

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (5)

7/21/2017 – After three games in the Match of the Century the score was 2:1 for the reigning World Champion. In game four Spassky played a well-prepared Sicilian and obtained a raging attack. Fischer defended tenaciously and the game was drawn. Then came a key game, about which the 1972 US Champion and New York Times and Chess Life correspondent GM Robert Byrne filed reports. In Reykjavik chess fan Lawrence Stevens from California did something extraordinary: he manually recorded the times both players had spent on each move.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (6)

7/26/2017 – In the sixth installment of our series we offer readers a glimpse of what had been happening behind the scenes of “The Match of The Century”, especially in the Russian camp. A tense Boris Spassky, cajoled by seconds Efim Geller and Nikolai Krogius, nevertheless failed to perform to the dismay of his friends and admirers. It’s also the story of a gamble that could have hurtled Bobby down the precipice in that fateful Game 6 of the match. A cautionary tale and object lesson for aspiring players.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (7)

8/4/2017 – After the first two traumatic games World Champion Boris Spassky was leading 2-0 in the Match of the Century. But then Fischer started to play and struck back: in the next eight games he scored 6½ points, chalking up a 6.5-3.5 lead. Games 8, 9 and 10 were quite spectacular, and are the subject of today's report. Younger players will also learn about "adjournments" and how exactly "sealed moves" were handled. Some were born after these practices were abandoned.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (8)

8/9/2017 – After ten games in the World Championship match in Reykjavik, 1972, the score was 6½-3½ for Challenger Bobby Fischer. The match seemed virtually over – in the last eight games Boris Spassky had only managed to score 1½ points. "If it had been the best of 12 games, as in the Candidates matches, Spassky would already have been on his way home..." wrote Garry Kasparov in his Great Predessors book. In game 11 Boris took on the Poisoned Pawn variation of the Najdorf Sicilian, even though he had obtained a lost position in game seven. Take a look at what happened.

No other World Champion was more infamous both inside and outside the chess world than Bobby Fischer. On this DVD, a team of experts shows you the winning techniques and strategies employed by the 11th World Champion.

Grandmaster Dorian Rogozenco delves into Fischer’s openings, and retraces the development of his repertoire. What variations did Fischer play, and what sources did he use to arm himself against the best Soviet players? Mihail Marin explains Fischer’s particular style and his special strategic talent in annotated games against Spassky, Taimanov and other greats. Karsten Müller is not just a leading international endgame expert, but also a true Fischer connoisseur.

"Game 13 puzzled many players even after it was finished. It was an epic battle and, according to Mikhail Botvinnik, the patriarch of Soviet chess, Fischer’s greatest achievement in the match. ‘Nothing like this had previously happened in chess,’ Botvinnik said. His former world championship challenger, David Bronstein, played the game over many times and it was an enigma to him. ‘Like a mysterious sphinx, it still teases my imagination,’ he said.

"Game 13 puzzled many players even after it was finished. It was an epic battle and, according to Mikhail Botvinnik, the patriarch of Soviet chess, Fischer’s greatest achievement in the match. ‘Nothing like this had previously happened in chess,’ Botvinnik said. His former world championship challenger, David Bronstein, played the game over many times and it was an enigma to him. ‘Like a mysterious sphinx, it still teases my imagination,’ he said.

In

In