Studying the classics

If you are a tournament player, familiar with current theory and practice, you have every reason to be sceptical about games from the past. More often than not, you are likely to say, “I have seen the classics. The rest is all old, outdated stuff. No one plays like that anymore”.

Maybe, you could have second thoughts on that one after seeing these games. All of them may be found in the MegaBase. Here I am offering more detailed annotations for two of them. I have left one of them alone. Not without reason. It is annotated by Tal.

A battle of generations

If you remember, last time we had seen here a dramatic battle from the Alekhine-Bogoljubow, World Championship 1934. Three decades later another duel took place. It was a Candidates’ Match for the World Championship.

Keres-Spassky 1965. The Estonian grandmaster was a legendary player with an illustrious career. He had crossed swords with the likes of Capablanca and Alekhine, not to mention his own contemporaries, Euwe and Reshevsky, to share first and second prize with Reuben Fine way back in AVRO 1938. Sadly, he had come second in three Candidates’ Tournaments, 1953, 1956 and 1959. Smyslov had outpaced him in 1953 and 1956, Tal in 1959. Close to 50 years of age, he was past his prime and also had serious health issues.

Smyslov cultivated a clear positional style and even in sharp tactical positions often relied more on his intuition than on concrete calculation of variations. Let our authors introduce you into the world of Vasily Smyslov.

Smyslov cultivated a clear positional style and even in sharp tactical positions often relied more on his intuition than on concrete calculation of variations. Let our authors introduce you into the world of Vasily Smyslov.Importantly, a kind of fatalism had seized his soul and he couldn’t believe Caissa would favour him in the fourth attempt, his having failed thrice. Livo Nei, who worked as his second, wrote that Keres could not bring himself to do his meticulous opening preparation. When Nei asked him to see some lines in the Ruy Lopez, Keres, replied, he had played it all his life and there was no need to do work on it all.

Keres and Nei, Beverwijk 1964 | Credit: E. Koch, ANEFO, via the Dutch National Archive

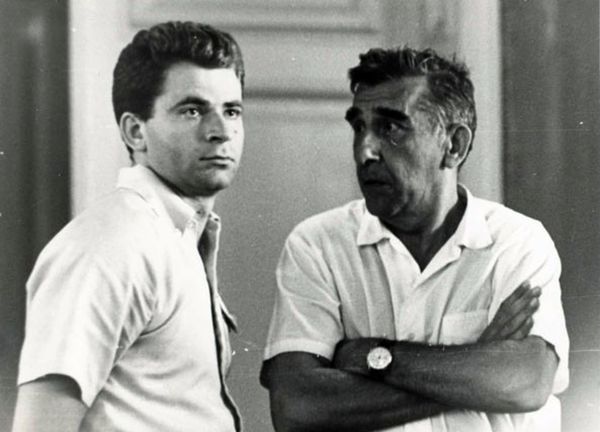

His youthful opponent, Spassky was in the prime of life and was determined to succeed after he had shared the first place with Tal, Larsen and Smyslov in the Amsterdam Interzonal 1964. He had also prepared quite a few surprises in the opening, the Leningrad Variation of the Nimzo-Indian and the Ruy Lopez, Keres’ own territory. In his preparation, Spassky was eminently helped by his trainer, Igor Bondarevsky, a veteran grandmaster who had shared the first prize with Andre Lilienthal way back in the 1940 USSR Championship.

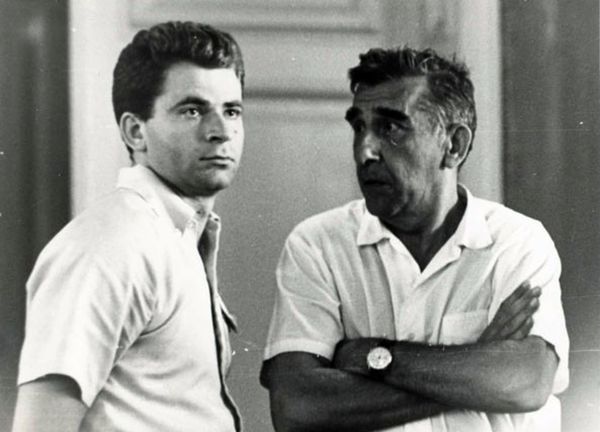

Spassky and Bondarevsky | Photo: chessmatenok.ru

The match that finally commenced was not without surprises. In game one, Spassky went all out to attack Keres with a series of pawn sacrifices and was brilliantly outplayed by Keres. The audience gave the veteran an ovation, with Spassky sportingly joining them. Keres played the second game without energy and Spassky came close to winning the king and knight ending in the session that followed adjournment. The Estonian escaped with a draw. However, it was cold comfort to him as he had allowed himself to be outplayed in his favourite opening, the Ruy Lopez. Meanwhile, Spassky sensed that his opponent was tiring early in the match. He pressed for advantage in the third game with an opening novelty in the Leningrad Variation of the Nimzo-Indian, a system that he had picked up from his trainer, Vladimir Zak and patented as his own. Here is what happened:

Why did Keres lose? He was a past master of the Nimzo-Indian. However, this Leningrad Variation presented a new set of problems. Although he was a versatile player, he was a classicist at heart. So in this game he could not bring himself to part with his bishop for the knight. Consequently his whole position deteriorated and he lost. Thereafter he played rather listlessly, losing games in his favourite Ruy Lopez and giving Spassky a lead in the match.

When everyone thought it was all over for Keres, he came storming back in game eight, sacrificing two pawns and conducting a brilliant attack, winning in 25 moves. Game nine was a draw. Everything hung in balance. In game ten, Spassky played the King’s Indian Defence to be met with the sharp Four Pawns Attack by Keres. In the ensuing battle, fortune changed hands more than once and sadly, it was Keres who lost his way in the maelstrom of complications.

Spassky and Keres in later years | Photo: Dmitri Prants, Estonian Sports and Olympic Museum

Years later Spassky recalled what Keres said to him after the Match,

You know, Boris Vasilievich, I am grateful to you. Through your way of playing I saw modern systems that a fifty-year-old player like me otherwise would not have known.

All ten games of the match may be found in the MegaBase. It’s tempting to look at the engine and pronounce judgement over the errors of omission and commission by both players. That is just not done. For the same reason, I have offered an historical perspective to the annotations on game three.

Spassky never forgot what a great player Keres was and treated him with great respect. The bond of friendship between the two remained till the end.

Match of the Century 1970

Five years after the Keres-Spassky Candidates’ Match, the scenario of the chess world changed. Now Boris Spassky was the world champion and the year saw a great contest, USSR versus Rest of the World. It was a four-game match on 10 boards. The competition saw the return of Bobby Fischer from his self-imposed exile, and the chess world was full of excitement.

The Soviet side was represented by Spassky, Petrosian, Korchnoi, Polugaevsky, Geller, Smyslov, Taimanov, Botvinnik (the Patriarch found himself on the 8th board!), Tal and Keres. There were two reserves, Bronstein and Stein. With as many as five world champions, the Soviet side lacked nothing.

Considered a master of prophylaxis, Petrosian sensed dangers long before they actually became acute on the board. In his prime, Petrosian was almost invincible. Let our authors introduce you into the world of Tigran Petrosian.

Considered a master of prophylaxis, Petrosian sensed dangers long before they actually became acute on the board. In his prime, Petrosian was almost invincible. Let our authors introduce you into the world of Tigran Petrosian.The Rest of the World Team was no less formidable. It was represented by Larsen, Fischer, Portisch, Hort, Gligoriċ, Reshevsky, Uhlmann, Matuloviċ, Najdorf and Ivkov. Late Max Euwe was the captain of the Rest of the World Team. The main issue for the former world champion was to resolve the question of the first board, with both Larsen and Fischer staking claim to the same. Fortunately, it was resolved by Bobby, who took a pragmatic decision and accepted the second board.

The outcome was a disaster for Petrosian, who did not expect to face Fischer opposite him. The American won with a fine score (+2 -0 =2). “Vidmar”, a perceptive reader of the News Page, here commented:

Fischer going to Board Two was able to leave Spassky with a false sense of superiority heading into 1972 and Petrosian with a definite sense of inferiority.

He was right. The defeat in the mini-match left terrible scars on Petrosian’s psyche, and he could not bring himself to play well against Fischer in the Candidates’ Final Match next year. He had lost the psychological duel here, and that was the beginning of the end.

To return to this Match of the Century, the score before the last round read:

USSR 15½ - 14½ Rest of the World

Excitement in the chess world was at its peak. Perhaps the Rest of the World Team could win 1 point more in the last round and draw level or even win the match with a score of 1½ points. As it turned out, the last round finished with a level score, 5:5.

The final result of the match read:

USSR 20½ - 19 ½ Rest of the World

In the post-mortem that followed the last round, the game Portisch-Korchnoi aroused controversy. Portisch had allowed a draw by threefold repetition when he had a superior — if not an immediately winning — position. Fischer accused Portisch of acting on Janos Kádár’s instructions to draw the game so that the Soviets would not lose this prestigious match. It met with a vehement denial from the proud Hungarian.

Fifty years later, in a ChessBase interview, Vlatimil Hort remembered the game and claimed the Portisch could have won the game. When the attention of the Hungarian veteran was drawn to this interview he was angry and maintained that the position was not so simple. Importantly, he refuted Fischer’s accusation that he drew on instructions from Janos Kádár.

MegaBase 2024 has brief Informant style notes on this encounter by both Korchnoi and Portisch. However, it’s better to see the game move by move with a complete commentary by the players:

Portisch’s decision here is understandable. In those days Korchnoi was known to play very well in time trouble and at the end of the game the position did look complicated with a couple of tactical tricks for Black. Decades later Portisch was to write that it had never been properly analysed. With the benefit of hindsight it is possible to find more in this game and the results are astonishing.

My analysis of this tragicomedy of a game is no reflection on the two great players. Remember that it was the last game of a tense match and both players tried to get a positive result. Great players are also human. It’s important for us to see how they think and what goes wrong there.

Let us learn together how to find the best spot for the queen in the early middle�game, how to navigate this piece around the board, how to time the queen attack, how to decide whether to exchange it or not, and much more!

Let us learn together how to find the best spot for the queen in the early middle�game, how to navigate this piece around the board, how to time the queen attack, how to decide whether to exchange it or not, and much more!

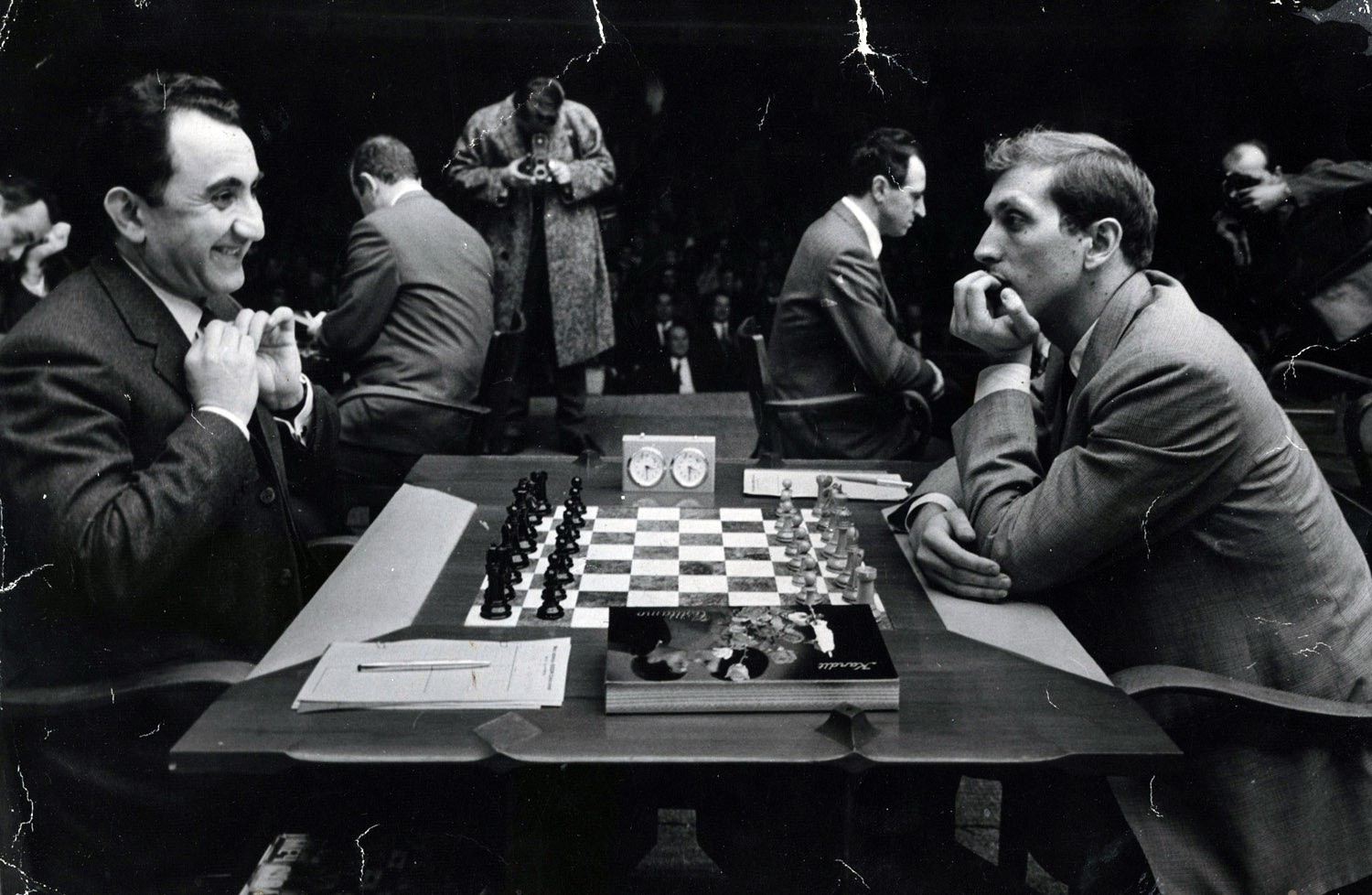

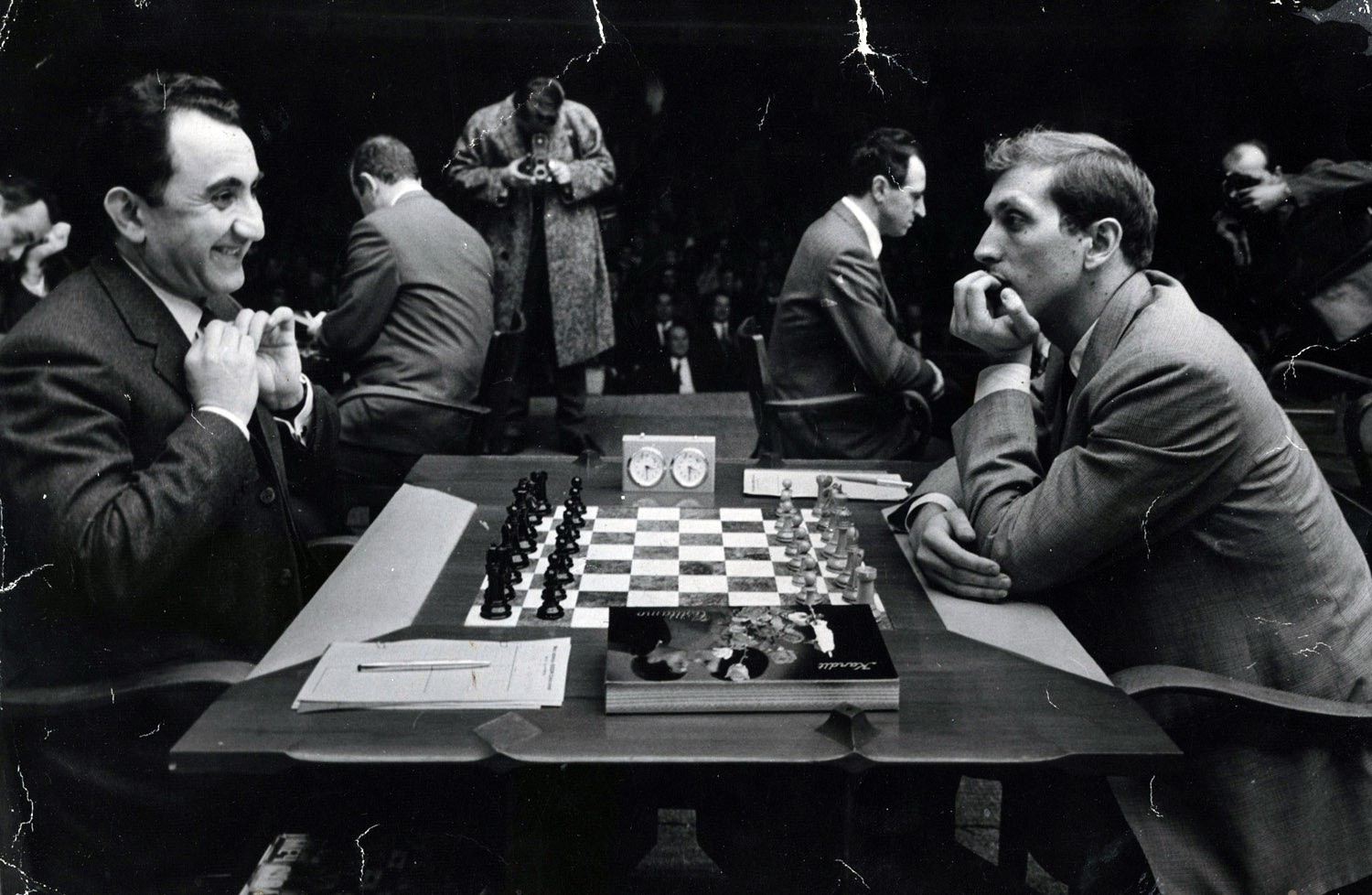

Korchnoi and Portisch in later years | Photo: chesspro.ru

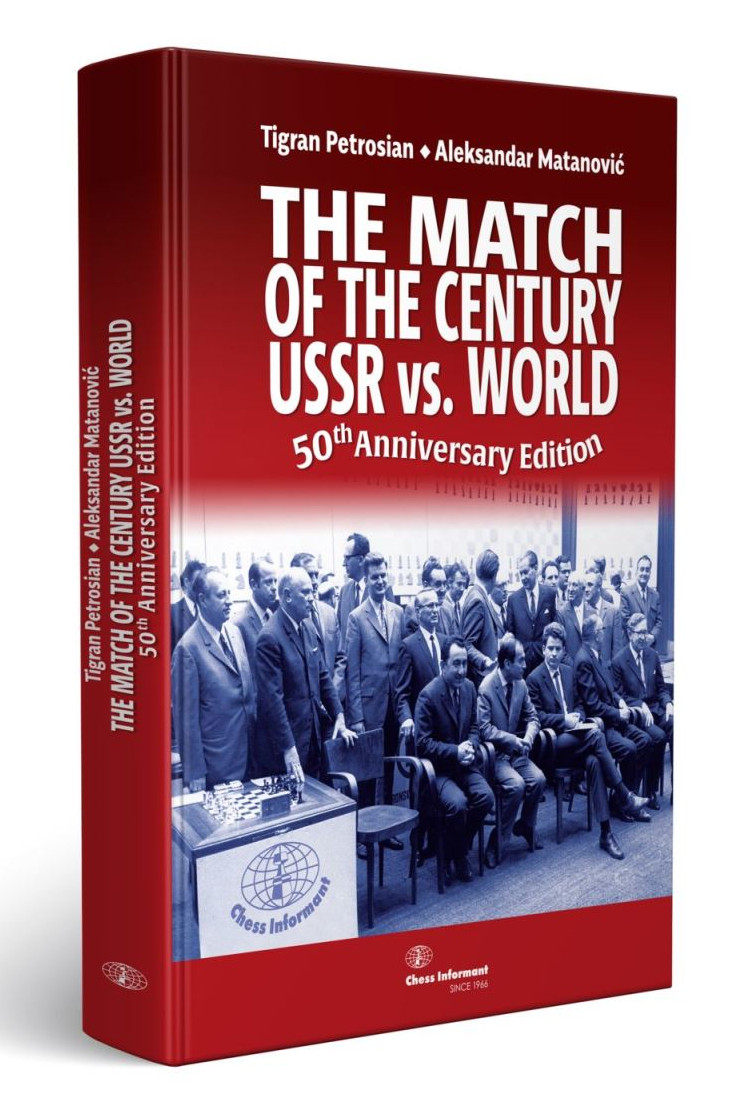

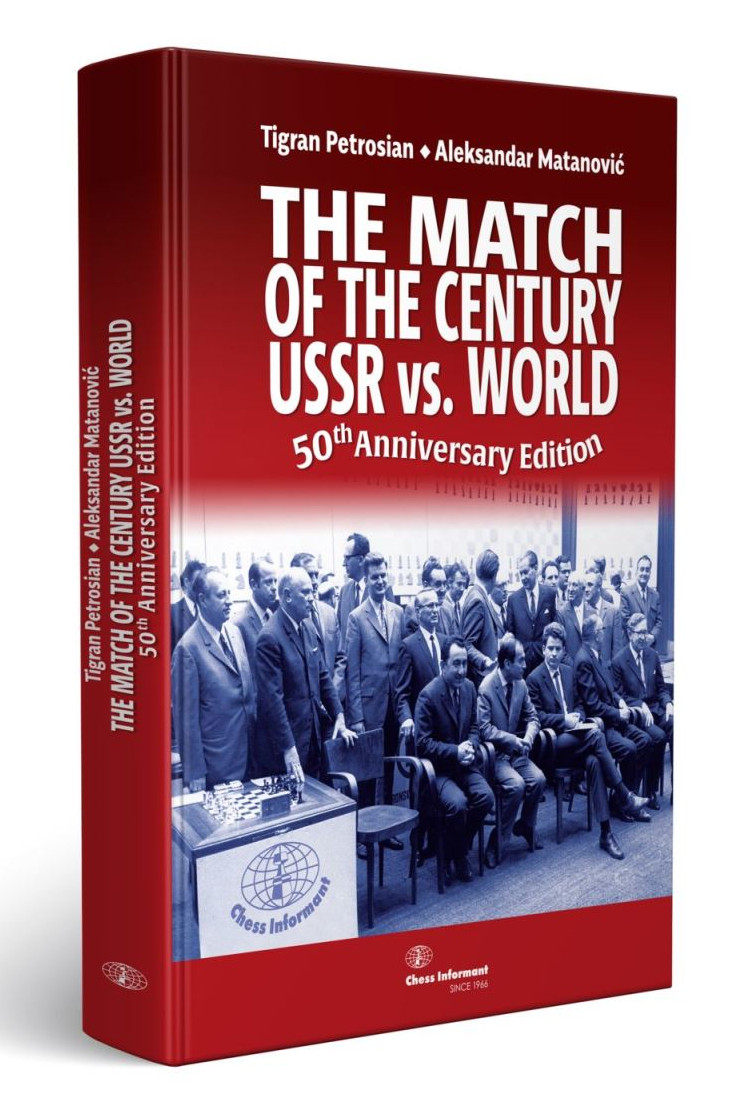

All the games of the Match of the Century may be found in the MegaBase here with Informant style notes. But I think it’s still important to know the inner thoughts of the players during the game. From this point of view, the following book is worth noting.

One remarkable feature of the book is that the games are annotated by the players themselves. It should serve as a useful companion to the MegaBase.

When Tal beat Spassky

As is known, both Tal and Spassky were old friends and keen rivals at the chessboard. Boris had lost a crucial game to Misha in the 1958 USSR Championship and missed the opportunity to participate in the World Championship cycle. As a result, Tal went on to win the cycle and became the world champion, beating Botvinnik in the match. Years later Spassky beat Tal in the Candidates’ Match 1965 on his way to the World Championship Match.

Tal-Spassky, Candidates’ Match 1965 | Photo: Eduard Pesov, Sputnik Magazine

Now we go fast-forward. Both players meet each other in Montral 1979. It’s a star-studded event with practically every leading grandmaster playing. Apart from three world champions, it includes Hübner, Larsen, Ljubojevic, Portisch and Timman among others. Sadly, the unofficial Soviet ban on Korchnoi holds, and only he is not invited.

As it happens, the reigning world champion, Anatoly Karpov, is in form and maintains a steady lead. He is closely followed by Tal. Spassky has handicapped himself with losses to Tal himself, Karpov and Larsen. Matters are not improved with the tough draws he had with other players. When he meets Tal again in the 9th round, he is in an aggressive mood and it is reflected in his ambitious play. Here is what happened in Tal’s own words:

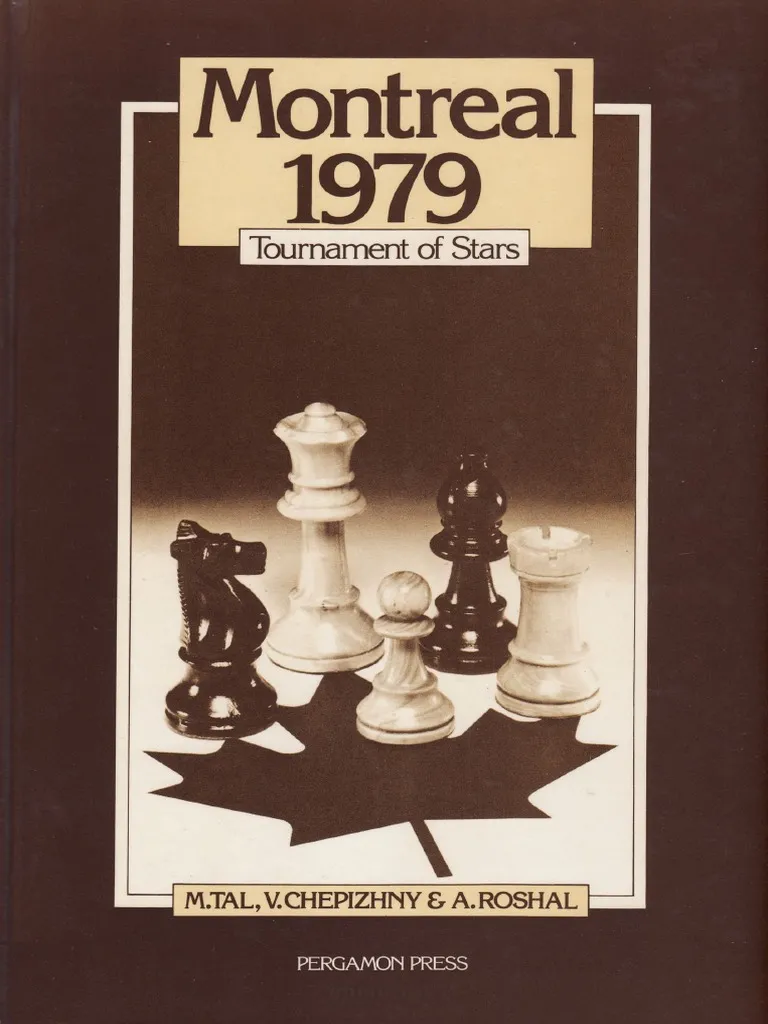

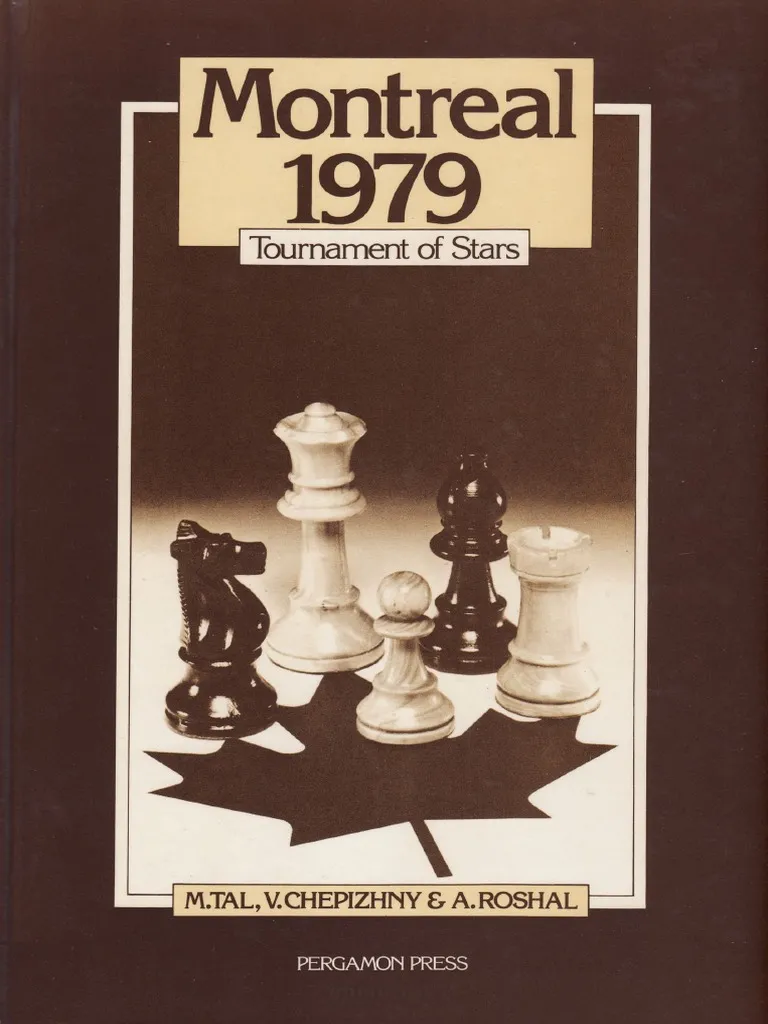

There is a fine book on this tournament with reports by Roshal, annotations by Tal and editing by Chepizhny.

A blast from the past

Not all modern commentators understand chess history, let alone appreciate our great chess heritage. A pleasant exception is Baskar Adhiban, who offers a modern perspective to games from the past without losing sight of the context in which they were played. A case in point is his commentary on the following encounter between Mark Taimanov and Boris Spassky. Before we see it, a few words of introduction are in order.

In this video course, experts including Dorian Rogozenco, Mihail Marin, Karsten Müller and Oliver Reeh, examine the games of Boris Spassky. Let them show you which openings Spassky chose to play, where his strength in middlegames were and much more.

In this video course, experts including Dorian Rogozenco, Mihail Marin, Karsten Müller and Oliver Reeh, examine the games of Boris Spassky. Let them show you which openings Spassky chose to play, where his strength in middlegames were and much more.

Taimanov-Spassky 1949 | Source: Historias del ajedrez soviético

Taimanov met Spassky when he was just a talented kid way back in 1949. They were to meet and compete together in many tournaments. In the years to come, both suffered in Fischer’s hands. That’s history. As colleagues, they remained friendly with each other, but fought hard over the board.

Taimanov-Spassky 1973 | Source: Douglas Griffin on X

Taimanov-Spassky, 1971 from MegaBase 2024

MegaBase 2024 offers a glimpse of our rich chess heritage. When you see the games of legendary players here, supplement your understanding by reading more about them and the times in which they lived. There chess historians show us the way.

Notes

1) Douglas Griffin on the Spassky-Keres 1965 Match: https://rb.gy/h8rm1i

2) Joosep Grents in the now defunct Chess24.com:

Paul Keres Part VIII: Gulliver among Liliputians

3) More on the 50th Anniversary Edition of the Book on the Match of the Century 1970:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/the-match-of-the-century-ussr-vs-the-world

4) Douglas Griffin on Tal in Montreal 1979: https://rb.gy/lzc4ss

Links

1. In a previous review of the MegaBase I dealt with its treatment of three World Championship matches:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/megabase-2022-three-epic-matches

2. In another review, I have dealt with the treatment of Carlsen and his peers, along with the play of veterans and young talents in the MegaBase:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/megabase-2023-modern-master-play

3. In the present series I have taken examples of Chess in the 21st Century from the MegaBase:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/megabase-2024-review-nagesh-havanur

4. I followed it up by narrating a World Championship duel that deserves to be better known:

https://en.chessbase.com/post/megabase-2024-revisited-nagesh-havanur

The ChessBase Mega Database 2024 is the premiere chess database with over 10.4 million games

from 1475 to 2023 in high quality.

.jpeg)