Avoiding interpretative issues

The following article was first published on Chessecosystems. Reproduced with kind permission.

While Gukesh Dommaraju avoids social media during ongoing tournaments, Ding Liren uses social media discussions to relax. The Chinese player might come across some debates, but he says they do not unsettle him. In fact, some discussions online have spiralled out of control, with commentators and streamers - even armed with opinionated engines - criticising the players and considering the level of play unimpressive. Objectively, the situation looks different.

One expert in data analysis and its interpretation is Mehmet Ismail, an economist and game theorist who works for Norway Chess. Ismail has analysed over a billion chess moves and developed calculations that go beyond merely interpreting accuracy data. Here are some of his most intriguing findings.

World Chess Championships: Increasingly precise

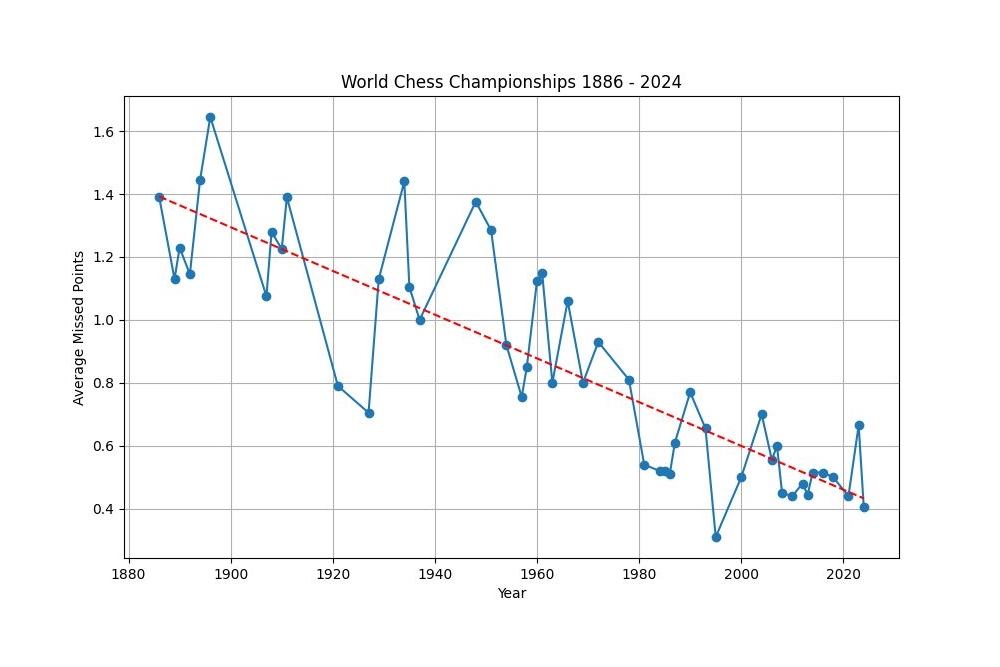

Mehmet Ismail's data visualisation shows a trend of decreasing errors (increasing accuracy) over time. This trend aligns with an independent Stockfish analysis at depth 20, other previous studies and the general assessment of leading grandmasters.

Until the 1921 match, players averaged over 1 missed point per game, meaning their mistakes amounted to more than 1 significant error per game. Over the years, the average number of missed points has significantly decreased.

This DVD allows you to learn from the example of one of the best players in the history of chess and from the explanations of the authors how to successfully organise your games strategically, and how to keep your opponent permanently under pressure.

This DVD allows you to learn from the example of one of the best players in the history of chess and from the explanations of the authors how to successfully organise your games strategically, and how to keep your opponent permanently under pressure."Even before chess engines, players learned from previous generations, and openings improved. As a result, overall accuracy increased. Chess engines have also contributed to this improvement".

Mehmet Ismail, December 2024.

However, Ismail believes chess is not only about precision but also about taking calculated risks. To measure this, the data expert developed the Game Intelligence (GI) Score, which captures a balance between playing the main line and deviating to take targeted risks. To calculate the players' GI scores, Ismail analysed more than a billion chess moves, over one million of which were made by the world's top grandmasters. The average human GI score is standardised to 100, with a standard deviation of 15, meaning 68% of chess players have a GI score between 85 and 115.

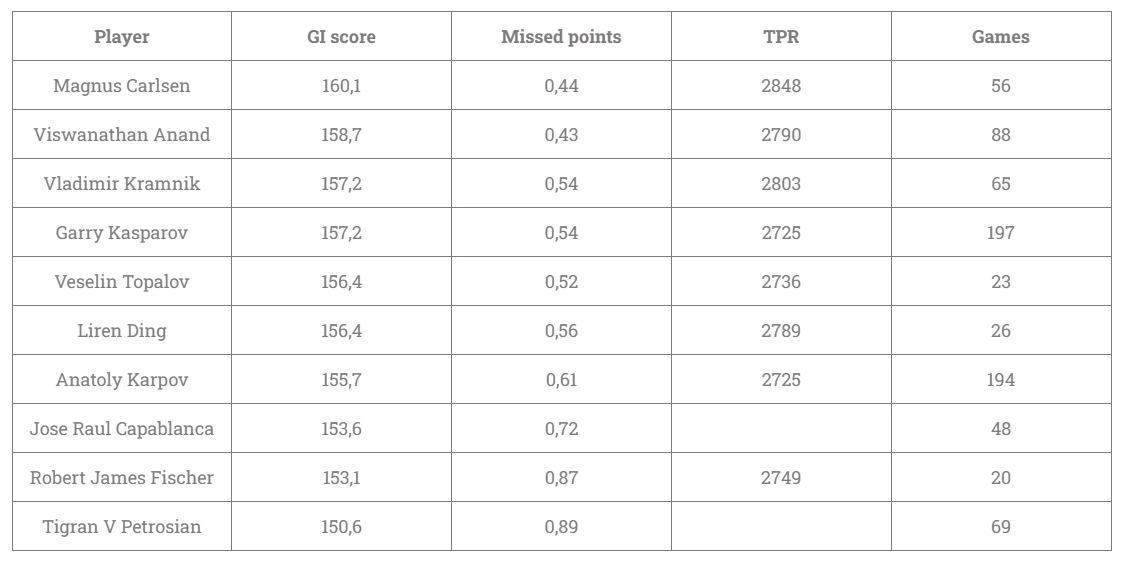

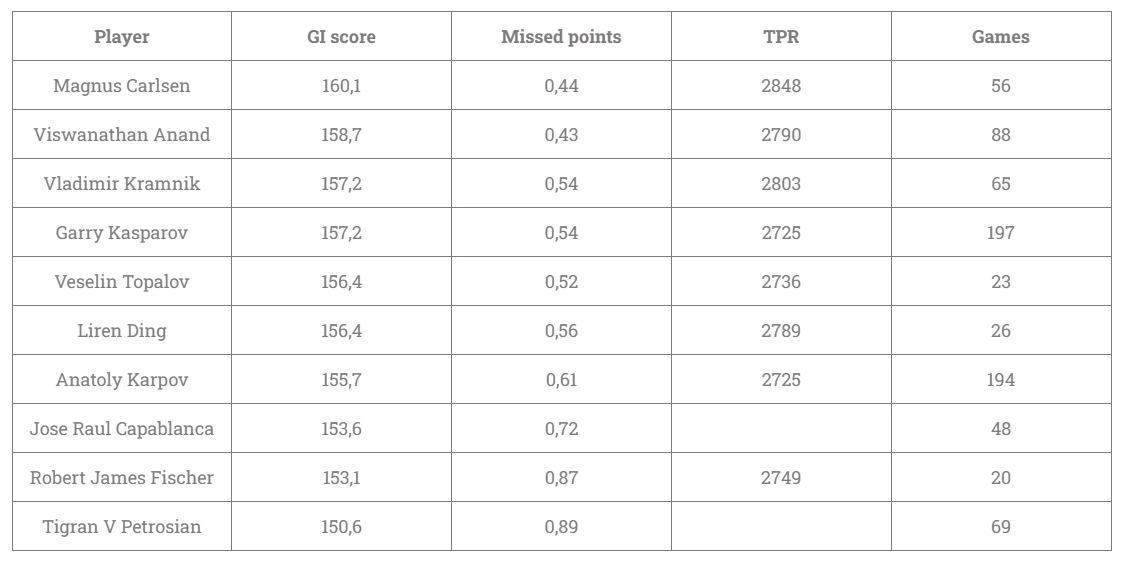

This table by Mehmet Ismail (as of 2024, 12 games played in Singapore) displays the results of world champions in World Championship matches.

How to interpret the data

As the table shows, Viswanathan Anand is the most accurate player, with an average score of 0.43 missed points per game. However, Magnus Carlsen stands out with the highest GI score of 160, indicating that Carlsen's playing style - deviating from the computer's top move at times - tends to provoke more mistakes from his opponents compared to other players.

World Championship match in Singapore: Ding v. Gukesh

According to the top chess engine Stockfish, both players performed at the same level during the first 12 games of the match, despite there being 4 decisive games. Their average missed points per game were just 0.4, suggesting that mistakes during the games amounted to less than 1 significant error per game. This high level of accuracy makes the match the second most accurate World Championship match in history, surpassed only by the legendary encounter between Garry Kasparov and Viswanathan Anand in 1995.

Photo: Eng Chin An (FIDE Chess)

"I can hardly believe this is the most accurate game so far".

Gukesh after Game 7

In this Fritztrainer: “Attack like a Super GM” with Gukesh we touch upon all aspects of his play, with special emphasis on how you can become a better attacking player.

In this Fritztrainer: “Attack like a Super GM” with Gukesh we touch upon all aspects of his play, with special emphasis on how you can become a better attacking player.

Photo: Maria Emelianova / Chess.com (FIDE Chess)

"Perhaps before this game".

Ding after Game 7

Mehmet Ismail

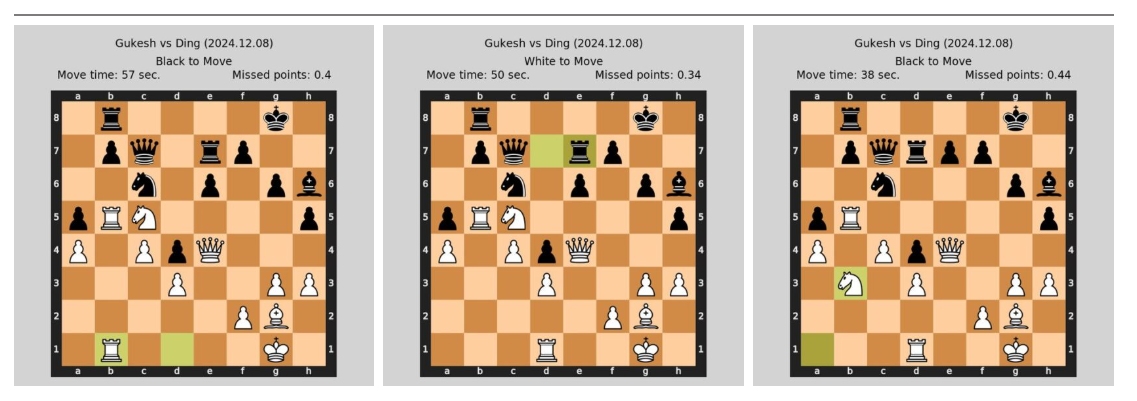

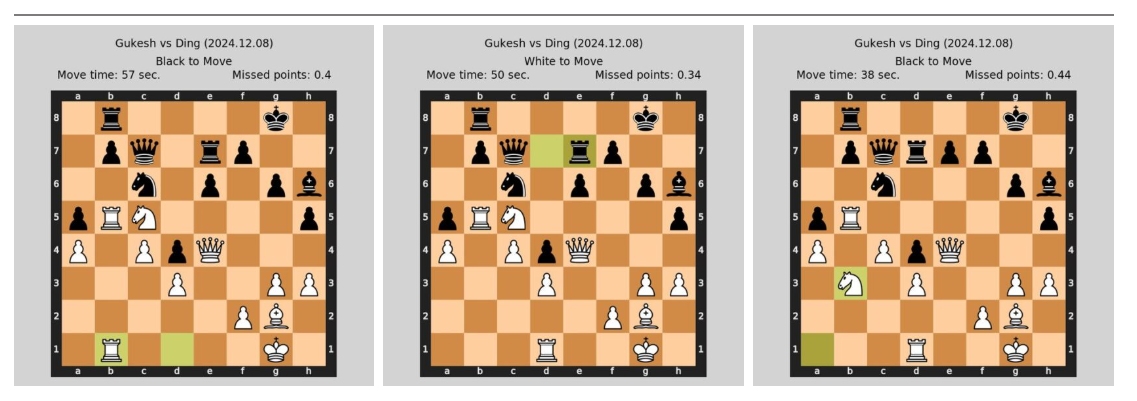

I would like to address three critical positions from Game 11 that are either on the verge of a mistake or where the players took a long time (over 15 minutes) to calculate.

For instance, in the first diagram, Ding played the queen to c8. This resulted in 0.4 missed points, meaning Ding transitioned from an almost objectively equal position to a losing one, as defined earlier. Note the logic: 0.5 missed points signify a transition from an equal to a losing position.

In the second diagram, the position shows Gukesh making an error with the move Rdb1, according to the engine. This results in 0.34 missed points, as White loses a significant advantage but remains in a better position. This is a smaller missed chance than Ding's mistake.

In the third diagram, the position before the mistake with the pawn move e7-e6 is depicted. This resulted in 0.44 missed points, which is significant.

On the limits of data analysis

Regarding the analysis of game quality in chess, Mehmet Ismail believes we should aim to measure the quality of play as accurately as possible. While engines are far stronger than humans, standard methods like centipawn loss or accuracy rates can lead to misleading results. Secondly, while analysing move quality is helpful, one should acknowledge its limitations.

For example, playing a perfect game and winning is entirely different from playing a perfect game and drawing. In both cases, the game might be perfect, but in the first case, the opponent makes a mistake, while in the second, they do not. The GI score aims to capture the differences between these distinct situations. According to Ismail, there are many more ways to make chess statistics more understandable and interpretable from a human perspective.

Definitions and methods used

Missed points

The values represent the average missed points per game. 1.00 and 0.50 missed points are equivalent to a game-losing error in a winning or drawn position, respectively. Conversely, 0 missed points indicate a perfect game. Missed points measure the points a player failed to achieve during a game, according to the engine. Each mistake is calculated based on the win-draw-loss probability of the engine's top move versus the actual move played.

For example, making an error in a winning position that results in a loss is equivalent to 1 missed point, while an error in a drawn position results in 0.5 missed points. A score of 0 missed points indicates a perfect game.

What is meant by Game Intelligence (GI)?

The GI score combines human performance with engine analysis and measures players' ability to take strategic risks. The GI score increases when players score more points and achieve success against stronger opponents, but it decreases with mistakes. The average GI score for a chess player is 100, with approximately 68% of players scoring between 85 and 115. Super-tournament winners typically achieve a GI score of 160 or higher.

Methodological notes

This video course includes GM Anish Giri's deep insights and IM Sagar Shah's pertinent questions to the super GM. In Vol.1 all the openings after 1.e4 are covered.

This video course includes GM Anish Giri's deep insights and IM Sagar Shah's pertinent questions to the super GM. In Vol.1 all the openings after 1.e4 are covered.Each mistake is calculated based on the win-draw-loss probability of the engine's best move versus the player's actual move. This approach avoids interpretative issues commonly associated with widely used average centipawn loss metrics. For an engine, a change in evaluation from +9.0 to +7.0 or from +2.0 to 0.0 both represent a loss of two pawn units; however, from a human and practical perspective, these two changes are vastly different. As a result, arithmetic calculations, such as averaging centipawn losses, generally fail to produce meaningful results from a human perspective.

Similarly, percentage accuracy scores can be unintuitive. For instance, in the current WCC, players achieved an accuracy of approximately 96% in both Game 2 and Game 7. However, in Game 2, they missed only 0.07 points, representing an almost perfect game, whereas in Game 7, they missed 1.00 point, equivalent to a decisive mistake in a winning position. Although Game 7 was drawn, it was a fundamentally different draw compared to Game 2, with its long duration distorting the accuracy score.

Mehmet Ismail considers all moves in a game starting from the first move for his analysis. He does not exclude opening moves, explaining that, first, there is no reliable dataset of opening moves played outside the book, and second, it would make little difference since missed points are a game-level statistic (they are not divided by the number of moves).

About Mehmet Ismail

Mehmet Ismail is a lecturer in Economics at the Department of Political Economy at King's College London. His academic background includes a PhD in Economics from Maastricht University. Mehmet also holds a Masters degree in Applied Mathematics from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and spent a semester at Bielefeld University as part of the Erasmus Mundus QEM programme.

Mehmet Ismail is a lecturer in Economics at the Department of Political Economy at King's College London. His academic background includes a PhD in Economics from Maastricht University. Mehmet also holds a Masters degree in Applied Mathematics from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and spent a semester at Bielefeld University as part of the Erasmus Mundus QEM programme.

Beyond academia, Mehmet is a passionate chess enthusiast and a former professional backgammon player. His passion for games extends far beyond playing; he is fascinated by the multifaceted world of games, exploring everything from theoretical foundations and practical applications to game design, fairness, and gameplay itself. Mehmet serves as a game theory expert for Norway Chess.

Links

Mehmet Ismail is a lecturer in Economics at the Department of Political Economy at King's College London. His academic background includes a PhD in Economics from Maastricht University. Mehmet also holds a Masters degree in Applied Mathematics from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and spent a semester at Bielefeld University as part of the Erasmus Mundus QEM programme.

Mehmet Ismail is a lecturer in Economics at the Department of Political Economy at King's College London. His academic background includes a PhD in Economics from Maastricht University. Mehmet also holds a Masters degree in Applied Mathematics from the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne and spent a semester at Bielefeld University as part of the Erasmus Mundus QEM programme.