The Four Continents has a visitor

Greenwich Village, New York City, 1960. A tall young man is moving along the street with purposeful strides. His destination: Four Continents, a shop that specializes in Soviet literature, periodicals and music records. Our hero, however, is only interested in Russian chess books and magazines. At seventeen he is not only the US Champion but also a serious contender for the world title. You have guessed his name by now. It’s Bobby Fischer.

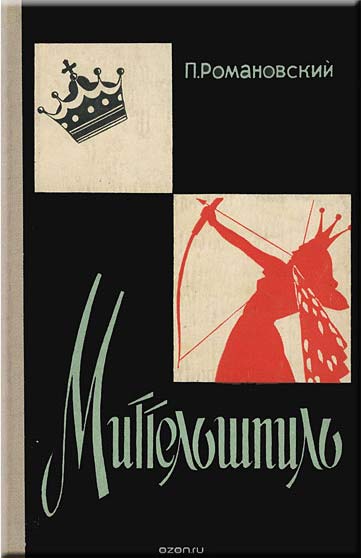

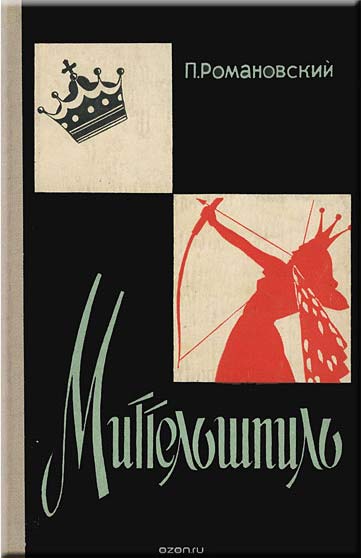

The staff at Four Continents have known him ever since he began to visit the place when he was a boy. Now he has grown up and he is very demanding as a customer. But then how do you say no to Bobby? Such is his charm. Anyway, today he is in for a surprise. There is a new book at the counter.

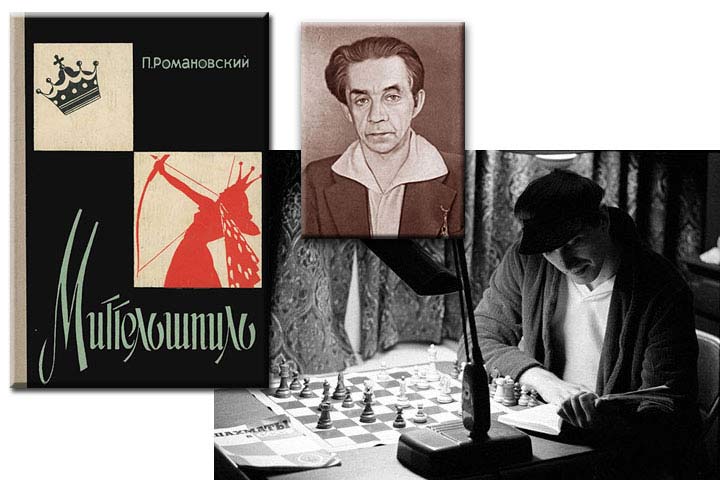

Bobby picks up the book and rushes home. When he scans the work, the very first game that he comes across is a little-known encounter, Klaman-Smyslov 1947, from the 15th USSR Championship. It’s a short game and in no more than 17 moves Smyslov lands in a lost position (never mind that he escaped with a draw). Bobby wonders, “How could it happen?” The author, Romanovsky has his own explanation. But Bobby is not convinced. He thinks, Black has not done badly and his play could be improved. He analyses for a while and then gives it up. Too much to prepare and too little time.

He leaves his fans stunned

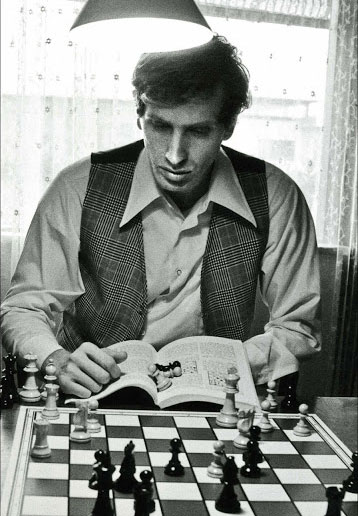

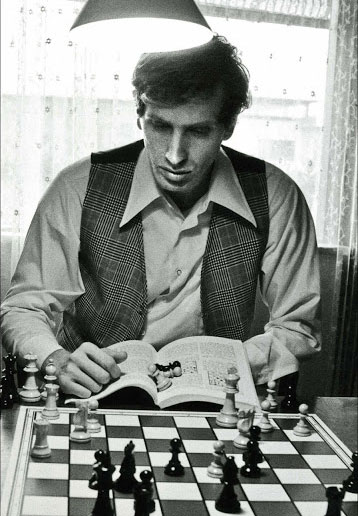

Years pass. Bobby crosses one hurdle after the other on his way to the World Championship. He wins the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal with a score of 18½ out of 23, far ahead of Larsen, Geller and Huebner who finished with 15. In Candidates Matches, first he beats Taimanov 6 : 0. This is followed by an even more spectacular victory over Larsen, 6 : 0. Only in the final match with Petrosian, he slows down a bit, prevailing over the Armenian with a score of. 6½ : 2½ (+5 -1 =3). The ensuing World Championship duel with Spassky is hailed as the Match of the Century. Trailing with a 2 : 0 deficit Bobby stages a dramatic comeback in a sensational match that results in the score of 12½ : 8½ (+7 -3 =11) in favour of the American.

Years pass. Bobby crosses one hurdle after the other on his way to the World Championship. He wins the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal with a score of 18½ out of 23, far ahead of Larsen, Geller and Huebner who finished with 15. In Candidates Matches, first he beats Taimanov 6 : 0. This is followed by an even more spectacular victory over Larsen, 6 : 0. Only in the final match with Petrosian, he slows down a bit, prevailing over the Armenian with a score of. 6½ : 2½ (+5 -1 =3). The ensuing World Championship duel with Spassky is hailed as the Match of the Century. Trailing with a 2 : 0 deficit Bobby stages a dramatic comeback in a sensational match that results in the score of 12½ : 8½ (+7 -3 =11) in favour of the American.

Photo: Harry Benson

His fans believe the domination of the Soviets has ended and a new era is about to begin, only to be disillusioned soon as their hero does not play a single serious game in the next three years. Worse, he forfeits his title after a breakdown of negotiations with the FIDE over the conditions of the match. After this disaster, he is no longer a reigning monarch, but a wandering king who moves restlessly from place to place. He shuns public gaze and seeks anonymity. He needs privacy.

A boy meets his hero

October 1990. Fifteen years have passed since he forfeited his title as world champion. The chess world has changed and it’s Garry Kasparov who has captured the imagination of the public. Bobby, though, continues to have a legion of fans. But nobody knows where he is. Their hero is looking for a quiet place to stay.

When he visits Lothar Schmid in Bamberg, the latter offers to help him. As is known, Schmid was the arbiter of the Fischer-Spassky World Championship Match and had earned Bobby’s trust on account of his decency and goodwill during the Match.

Pulvermühle, contemporary photo | Literatur Portal Bayern

Schmid arranges for Bobby’s stay as a house guest in a countryside inn, Pulvermühle, in Waischenfeld, Bavaria. The owner, Kaspar Bezold, is a friendly host and a dedicated chess amateur himself. Aware that the presence of Bobby Fischer would create a stir and draw the attention of the press, Bezold has him registered under an assumed name. A satisfactory arrangement for the recluse.

He has young Michael Bezold for company. The 18-year-old is a talented player. In the ensuing three months, they spend quite some time together playing and analyzing. As Michael recalled later:

"He was obsessed with a game… and the question was whether or not to move the pawn to h6. This was the only question. And he said he’d been analyzing this game for more than 30 years, and he couldn’t figure out whether it’s better to play h6 or not. It was fantastic."

Michael Bezold

But where was the position? There would be any number of positions in which Black would have that kind of choice to make. So I decided to ask Michael Bezold, now a well-known grandmaster. Here is what he wrote:

Dear Prof.

I do remember that episode, to move or not to move the pawn to h6. But I have completely no memory anymore which game it was.

Another story about Bobby: I like studies very much, especially endgame studies. From to time I showed some of them to Bobby. Of course he was very interested. He solved quite a lot instantly. But there were also some very difficult ones. When he could not solve one after something like ten minutes he would retire into his room and come out only when he had discovered the solution. Sometimes it took hours. But he never appeared before then. In his opinion there was nothing in chess that he could not find.

Best regards,

Michael Bezold

Sadly, the idyll did not last, as a German journalist recognized him and before the rest of the press hounds caught the scent, Bobby checked out of the inn and was not seen there again.

The wandering king finds a haven

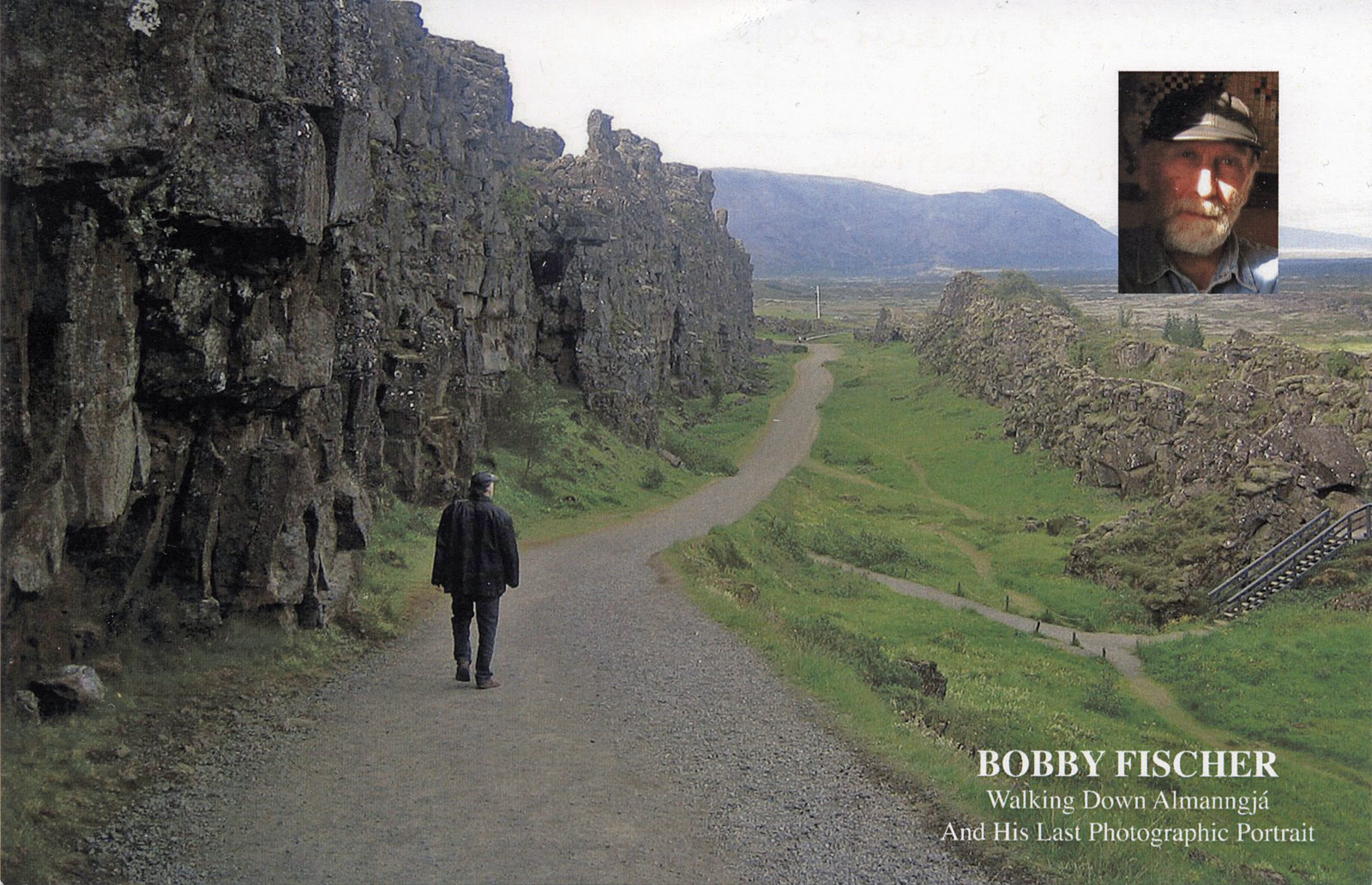

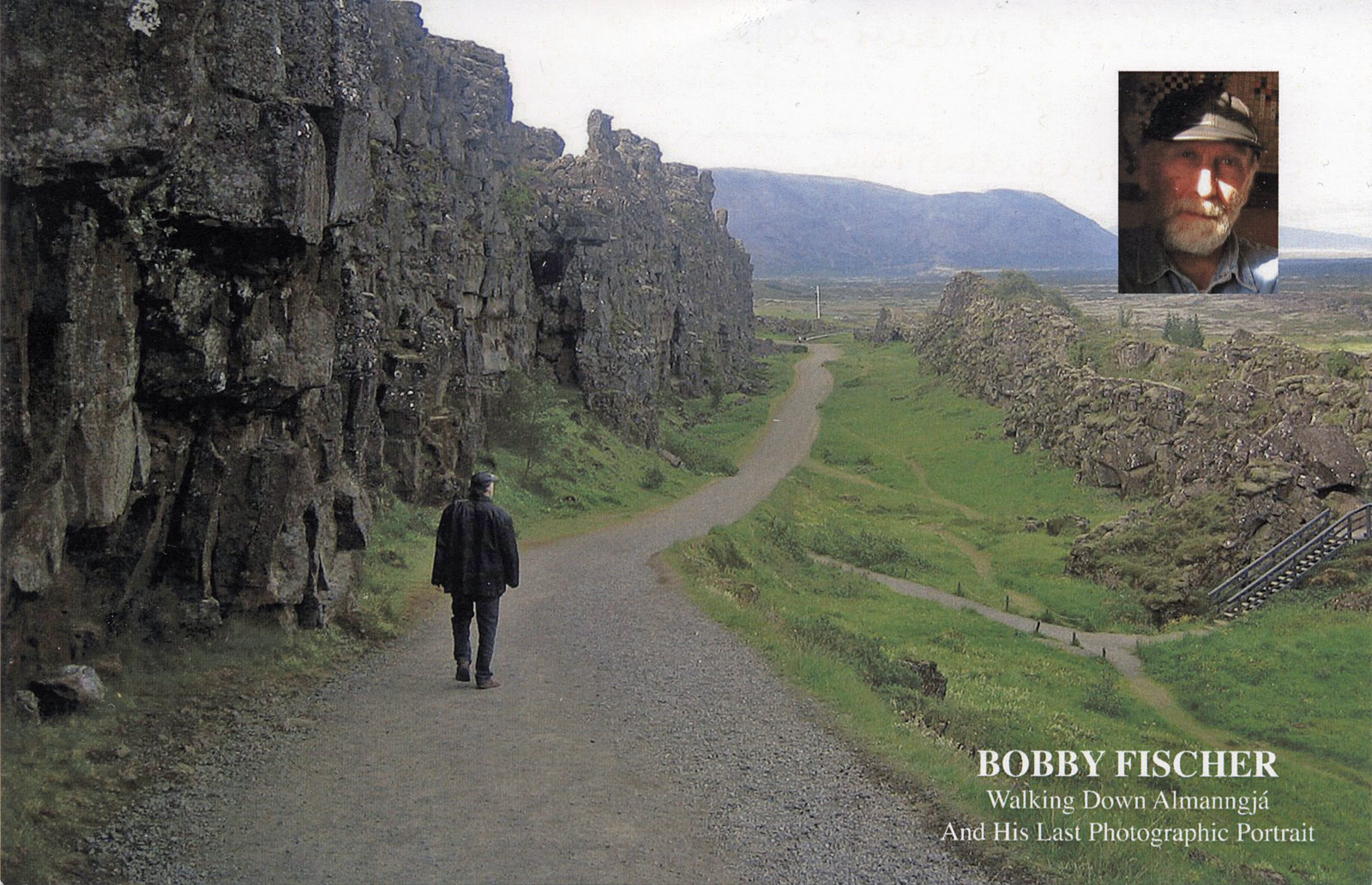

I shall not recall the painful period that followed from the Fischer-Spassky Return Match 1992, to Bobby’s incarceration in a Japanese prison till March 2005. It would suffice to say that Bobby’s fans rejoiced when he was set free thanks to the efforts of a dedicated band of friends. It was they who arranged for his asylum in Reykjavik, with Miyoko Watai, his companion helping out at the Tokyo end. At last the wandering king had found a haven of peace.

Photo: Einar Einarsson

There are several accounts of those last years in Reykjavik. In a way, his old passion for chess had abated, though he still recalled old games (especially, his own from the historic 1972 World Championship).

Now we return to the narrative from Garðar Sverrisson, his friend in Reykjavik:

…he now wanted to show me a position in the Queen’s Indian Defense that had come up in a game Smyslov had played in the 1947 Soviet Championships. That game was to be found in Romanovsky’s magnificent textbook. On Smyslov’s behalf he wanted to try to find an improvement that he was sure must be there to be found. When I thought we had spent more than enough time on experiments in our hunt for a better answer for Smyslov, Bobby was far from ready to quit. I opined that at this point, we were unlikely to find the good counter-move that Bobby was so certain was hiding somewhere in the position. But he kept on scrutinizing the board and turning Smyslov’s options over in his mind.

…he now wanted to show me a position in the Queen’s Indian Defense that had come up in a game Smyslov had played in the 1947 Soviet Championships. That game was to be found in Romanovsky’s magnificent textbook. On Smyslov’s behalf he wanted to try to find an improvement that he was sure must be there to be found. When I thought we had spent more than enough time on experiments in our hunt for a better answer for Smyslov, Bobby was far from ready to quit. I opined that at this point, we were unlikely to find the good counter-move that Bobby was so certain was hiding somewhere in the position. But he kept on scrutinizing the board and turning Smyslov’s options over in his mind.

“I don’t think there’s anything there, Bobby.”

“Wait, wait,” he said, unwilling to quit.

“But we’ve exhausted all the options.”

“Don’t be too sure, Garðar. Don’t be too sure.”

No other World Champion was more infamous both inside and outside the chess world than Bobby Fischer. On this DVD, a team of experts shows you the winning techniques and strategies employed by the 11th World Champion.

Grandmaster Dorian Rogozenco delves into Fischer’s openings, and retraces the development of his repertoire. What variations did Fischer play, and what sources did he use to arm himself against the best Soviet players? Mihail Marin explains Fischer’s particular style and his special strategic talent in annotated games against Spassky, Taimanov and other greats. Karsten Müller is not just a leading international endgame expert, but also a true Fischer connoisseur.

“Woodford” makes a discovery

What was Bobby looking for? It was the position below and it happens to be taken from the very first game, Klaman-Smyslov 1947 in Romanovsky’s book. We owe that discovery to an alert reader, going by the name of "Woodford", in the feedback section of this news page.

Houdini loves it all

In the first part of this article, I analyzed the position and thought Black would find salvation with 11…h6 even if it invited the sacrifice 12.Bxh6. Surely, there would be no greater tribute to Bobby if I succeeded in showing that his line worked. Sadly, it fails and it took Houdini to find that out. The final position is quite picturesque.

Houdini 6 continues where its predecessor left off, and adds solid 60 Elo points to this formidable engine, once again making Houdini the strongest chess program currently available on the market.

Houdini 6 continues where its predecessor left off, and adds solid 60 Elo points to this formidable engine, once again making Houdini the strongest chess program currently available on the market.

I am afraid, that’s the end of the road for 11…h6. The only consolation is that there are improvements for Black before.

[Event "?"] [Site "?"] [Date "1947.02.12"] [Round "?"] [White "Klaman, Konstantin"] [Black "Smyslov, Vassily V"] [Result "*"] [ECO "A47"] [Annotator "Nagesh Havanur"] [PlyCount "39"] [EventDate "1947.??.??"] 1. d4 Nf6 2. Nf3 ({Deviating from} 2. c4 {to avoid Smyslov's opening preparation}) 2... b6 3. Nc3 (3. c4 e6 4. Nc3 Bb4 {transposes to the Nimzo-Indian.}) ({and} 3. g3 Bb7 4. Bg2 {to regular lines of the Queen's Indian.}) (3. Bg5 Bb7 4. Bxf6 {inflicting doubled pawns is a Palliser recommendation. However, with two bishops Black is not without resources.}) 3... Bb7 4. Bg5 d5 {Romanovsky is critical of this move as it allows an early occupation of e5 by the White knight. However, there may be ways to neutralize the pressure.} (4... c5 {only allows White to expand with} 5. d5) 5. e3 e6 ({ not} 5... Ne4 6. Bb5+ c6 7. Bd3 Nxg5 8. Nxg5 $16) 6. Ne5 Be7 ({If} 6... Nbd7 $2 7. Bb5 c6 8. Nxc6 Bxc6 9. Bxc6 Rc8 10. Bb5 $16 {White is a pawn up.}) 7. Bb5+ c6 ({not} 7... Nbd7 $2 8. Bxf6 gxf6 9. Bxd7+ Kf8 10. Bc6 $18) 8. Bd3 c5 { This move could have waited.} ({It's preferable to complete development with} 8... Nbd7) 9. O-O {A routine move that allows Black to equalize.} ({Instead} 9. Bb5+ {deserves attention.} Kf8 {(Romanovsky suggestion) threatening...c4, encircling and trapping the bishop White may try} (9... Nbd7 $2 10. Bxf6 gxf6 11. Bxd7+ Kf8 12. Bc6 $18) (9... Nfd7 10. Bf4 $14 (10. h4 $5)) 10. Qf3 Qc8 11. Be2 $14) 9... O-O ({Romanovsky recommends} 9... a6 {preventing Bb5+ and preparing...Nbd7 followed by queenside expansion}) 10. Qf3 Nc6 (10... Nfd7 11. Bf4 ({After} 11. Qh3 {Abernathy's move} f5 {is satisfactory.}) 11... Nxe5 12. Bxe5 Nd7 {also looks reasonable. However, White has a slight advantage on account of better development.}) 11. Qh3 {Now Bobby Fischer hoped to rescue the line with} h6 {However, after} ({The actual game continued} 11... g6 $2 { If Black is allowed to play...Re8 followed by...Bg7, he would have a satisfactory position. That is not to be.} 12. Ba6 $1 Qc8 (12... Bxa6 13. Nxc6 Qd7 14. Nxe7+ Qxe7 15. Qh4 Kg7 16. Bh6+ Kg8 17. Bxf8 Rxf8 18. Rfe1 $16) 13. Nxc6 Qxc6 14. Bxb7 Qxb7 15. Qh4 Kg7 16. Bh6+ Kg8 17. Bg5 {This leads to a draw by repetition of moves. It's possible that Klaman was in time trouble here.} ({ Otherwise he would have played} 17. Bxf8 Rxf8 18. f3 $16 {with an exchange up and the better position.}) 17... Kg7 18. Bh6+ Kg8 19. Bg5 Kg7) 12. Bxh6 { An obvious sacrifice.} (12. Bf4 Rc8 $11 ({or} 12... Nb4 13. Rac1 Nxd3 14. cxd3 $13)) 12... c4 {The best practical chance.} ({not} 12... gxh6 $2 13. Qxh6 Nxe5 14. dxe5 Ne4 15. f4 {followed by 16.Rh3 winning,}) 13. Bxg7 Kxg7 14. Qg3+ Kh8 15. Qh4+ Kg7 16. Qg5+ Kh8 17. Qh6+ Kg8 18. f4 Nxe5 ({Abernathy, a chess aficianado gives} 18... cxd3 19. Rf3 Nxe5 20. fxe5 Ng4 21. Rg3 f5 22. exf6 Bxf6 23. Rxg4+ Kf7 24. Qh7+ Ke8 25. Qxb7 $18) 19. fxe5 Ne4 {preparing to play...Bg5 and...f5} 20. Rf6 $1 $18 *

When Bobby was young

Would Bobby have found this out? The younger man had not managed it only for want of time and focused attention. Otherwise, it was not beyond him. Take a look at the position here:

[Event "USA-ch "] [Site "?"] [Date "1963.12.30"] [Round "?"] [White "Fischer, Robert James"] [Black "Benko, Pal C"] [Result "1-0"] [ECO "B09"] [Annotator "Bobby Fischer"] [PlyCount "43"] [EventDate "1963.??.??"] 1. e4 g6 2. d4 Bg7 3. Nc3 d6 4. f4 Nf6 5. Nf3 O-O 6. Bd3 Bg4 7. h3 Bxf3 8. Qxf3 Nc6 9. Be3 e5 10. dxe5 dxe5 11. f5 gxf5 12. Qxf5 Nd4 13. Qf2 Ne8 14. O-O Nd6 15. Qg3 Kh8 16. Qg4 c6 17. Qh5 Qe8 18. Bxd4 exd4 {[#]} 19. Rf6 $1 {A bolt from the blue!} Kg8 $8 ({On} 19... dxc3 {or 19...Bxf6} 20. e5 {mates.}) 20. e5 h6 21. Ne2 $1 {Black resigns. There is no defense to the threat of Rxd6. On} ({ Black was hoping for} 21. Rxd6 $2 Qxe5 $1 {and he survives to an ending.}) 21... Nb5 ({Or} 21... Bxf6 22. Qf5 {forces mate.}) 22. Qf5 {wins. (The game is fully annoated by Bobby Fischer in his book, "My 60 Memorable Games".)} 1-0

The older man could not do it. He was fighting a losing battle against time, and in the end Death had the last word.

The Maestro from Moscow did not know

The pity is that Vassily Smyslov never came to know Bobby was so much interested in this game. The grand old man would only have been pleased. If Bobby had interacted with Smyslov and discussed this game with him, the two legends together would have come up with a wealth of variations. That is lost to posterity.

The pity is that Vassily Smyslov never came to know Bobby was so much interested in this game. The grand old man would only have been pleased. If Bobby had interacted with Smyslov and discussed this game with him, the two legends together would have come up with a wealth of variations. That is lost to posterity.

Barden draws a parallel

The writing of this feature for ChessBase had one happy windfall. Leonard Barden, the doyen of English chess journalism, happened to read the first part of this article. He is known as an authority on openings – in the good old days he was called “The Walking Encyclopedia” by late Assiac. Barden informed me that the tactical theme, Bd3-a6 is seen in a well-known trap in Queen’s Indian Defence. When I checked MegaBase 2018, I found as many as 24 games with this idea. Here is one of them:

[Event "FRA-ch Accession Pau(6) "] [Site "?"] [Date "2008.??.??"] [Round "?"] [White "Heinis, Vincent"] [Black "Houriez, Clement"] [Result "1-0"] [ECO "E14"] [WhiteElo "2116"] [BlackElo "2276"] [Annotator "Nagesh Havanur"] [PlyCount "35"] [EventDate "2008.??.??"] 1. d4 Nf6 2. Nf3 b6 3. c4 e6 4. e3 (4. a3 {preventing...Bb4 and preparing b2-b4 is the Petrosian Variation.}) 4... Bb7 {The Queen's Indian defence} 5. Bd3 {The Classical Variation} ({White avoids the Nimzo-Indian with} 5. Nc3 Bb4) (5. g3 {followed by Bg2 is in currently in vogue.}) 5... c5 {seeking complex play} (5... d5 {followed by...Bd6,...0-0 and...Nbd7 is a solid alternative.}) 6. O-O Be7 (6... d6 {followed by ...Nbd7, ...Be7 and...0-0 leading to a hedgehog formation is also seen here.}) 7. Nc3 cxd4 (7... d6 {followed by ... Nbd7 and...0-0 is still possible.}) 8. exd4 d5 {This leads to a sharp, double-edged game.} 9. cxd5 Nxd5 10. Ne5 O-O 11. Qg4 (11. Qh5 Nf6 {comes to the same thing.}) 11... Nf6 (11... f5 $5 12. Qe2 Bf6 {is the other line.}) 12. Qh4 Nc6 (12... Ne4 $1 13. Qh3 Qxd4 14. Bf4 Nf6 15. Ne2 Qa4 16. Bg5 g6 17. Rac1 Na6 {White has some compensation for the pawn with his better development. However, Black is catching up with counterplay. This line needs more tests over the board.}) 13. Bg5 g6 $2 (13... Nxe5 $1 14. Bxf6 Nxd3 15. Bxe7 Qc7 16. Bxf8 Rxf8 $44 {Black has compensation for the exchange with his active knight and bishop.}) 14. Ba6 $1 Nxe5 (14... h6 15. Bxh6 Nd5 16. Qh3 Nxc3 17. bxc3 Bxa6 18. Nxc6 Qd6 19. Nxe7+ Qxe7 20. Bxf8 Rxf8 21. Rfe1 Bc4 22. Qh6 {1-0, Yusupov, Artur-Gurevich,Dmitry,HB Global 2005}) 15. dxe5 h6 16. Bxf6 Bxf6 17. exf6 Bxa6 18. Rfd1 $18 1-0

It only remains for me to thank everyone involved in this journey.

First, there are the readers of this news page, especially, "Woodford", "Abernathy" and "clement41", whose lively interest and comment spurred me on. Over the years GM Michael Bezold must have answered endless questions on Bobby’s visit and stay at the family inn. Nevertheless, he patiently answered my query and came up with a nugget of info. Last, but not least I owe a debt to Leonard Barden for pointing out the tactical theme, Ba6 in the opening. My generation learnt from his writings for years and it still continues to learn.

Correction: The Klaman-Smyslov, 1947 diagram was initially missing a knight on f6.

Links

Years pass. Bobby crosses one hurdle after the other on his way to the World Championship. He wins the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal with a score of 18½ out of 23, far ahead of Larsen, Geller and Huebner who finished with 15. In Candidates Matches, first he beats Taimanov 6 : 0. This is followed by an even more spectacular victory over Larsen, 6 : 0. Only in the final match with Petrosian, he slows down a bit, prevailing over the Armenian with a score of. 6½ : 2½ (+5 -1 =3). The ensuing World Championship duel with Spassky is hailed as the Match of the Century. Trailing with a 2 : 0 deficit Bobby stages a dramatic comeback in a sensational match that results in the score of 12½ : 8½ (+7 -3 =11) in favour of the American.

Years pass. Bobby crosses one hurdle after the other on his way to the World Championship. He wins the Palma de Mallorca Interzonal with a score of 18½ out of 23, far ahead of Larsen, Geller and Huebner who finished with 15. In Candidates Matches, first he beats Taimanov 6 : 0. This is followed by an even more spectacular victory over Larsen, 6 : 0. Only in the final match with Petrosian, he slows down a bit, prevailing over the Armenian with a score of. 6½ : 2½ (+5 -1 =3). The ensuing World Championship duel with Spassky is hailed as the Match of the Century. Trailing with a 2 : 0 deficit Bobby stages a dramatic comeback in a sensational match that results in the score of 12½ : 8½ (+7 -3 =11) in favour of the American.

…he now wanted to show me a position in the Queen’s Indian Defense that had come up in a game Smyslov had played in the 1947 Soviet Championships. That game was to be found in Romanovsky’s magnificent textbook. On Smyslov’s behalf he wanted to try to find an improvement that he was sure must be there to be found. When I thought we had spent more than enough time on experiments in our hunt for a better answer for Smyslov, Bobby was far from ready to quit. I opined that at this point, we were unlikely to find the good counter-move that Bobby was so certain was hiding somewhere in the position. But he kept on scrutinizing the board and turning Smyslov’s options over in his mind.

…he now wanted to show me a position in the Queen’s Indian Defense that had come up in a game Smyslov had played in the 1947 Soviet Championships. That game was to be found in Romanovsky’s magnificent textbook. On Smyslov’s behalf he wanted to try to find an improvement that he was sure must be there to be found. When I thought we had spent more than enough time on experiments in our hunt for a better answer for Smyslov, Bobby was far from ready to quit. I opined that at this point, we were unlikely to find the good counter-move that Bobby was so certain was hiding somewhere in the position. But he kept on scrutinizing the board and turning Smyslov’s options over in his mind.

The pity is that Vassily Smyslov never came to know Bobby was so much interested in this game. The grand old man would only have been pleased. If Bobby had interacted with Smyslov and discussed this game with him, the two legends together would have come up with a wealth of variations. That is lost to posterity.

The pity is that Vassily Smyslov never came to know Bobby was so much interested in this game. The grand old man would only have been pleased. If Bobby had interacted with Smyslov and discussed this game with him, the two legends together would have come up with a wealth of variations. That is lost to posterity.