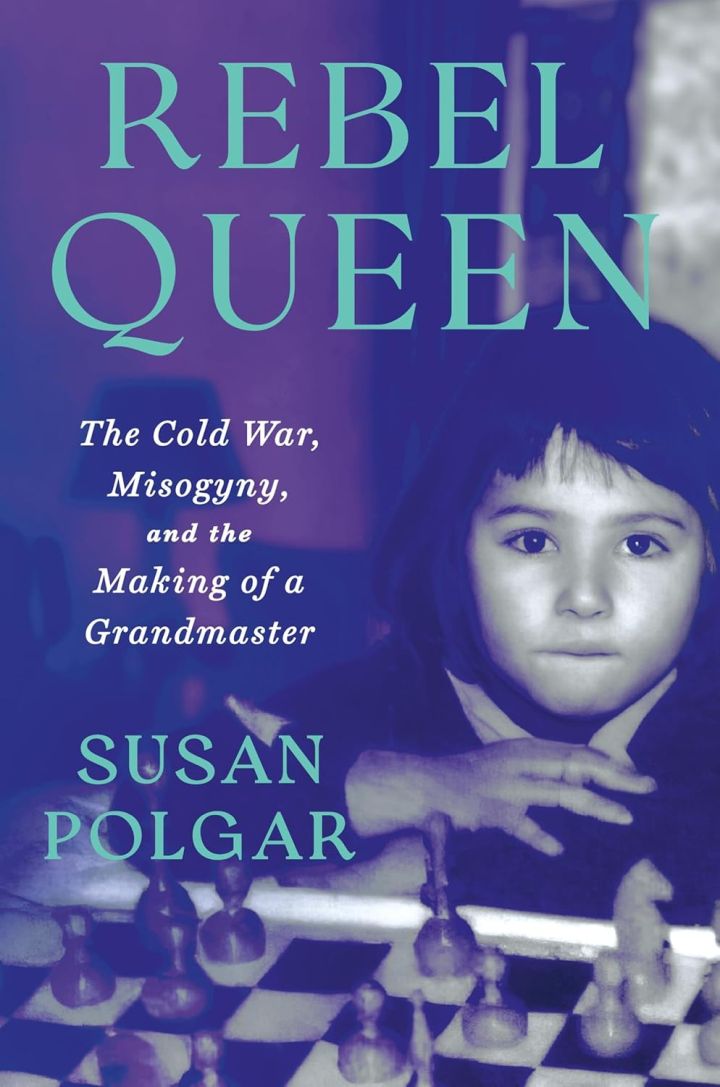

Born to a poor Jewish family in Cold War Budapest, Susan (Hungarian: Zsuzsa) Polgar would emerge as the one of the greatest female chess players the world had ever seen. She became the highest rated female chess player on the planet, and the first woman to qualify for the men's World Chess Championship cycle. She went on to achieve the game's triple crown, holding Womens' World Championship titles in all three major chess time formats (blitz, rapid, and classical).

Born to a poor Jewish family in Cold War Budapest, Susan (Hungarian: Zsuzsa) Polgar would emerge as the one of the greatest female chess players the world had ever seen. She became the highest rated female chess player on the planet, and the first woman to qualify for the men's World Chess Championship cycle. She went on to achieve the game's triple crown, holding Womens' World Championship titles in all three major chess time formats (blitz, rapid, and classical).

Before her improbable rise, it was taken for granted that women were incapable of excellence in the game of chess. But the extraordinary training imparted by her father László on his three daughters disproved this notion. In fact Susan's sister Judit became the strongest female chess player in the history of the game, rising at one state to the top ten in the men's (the open) list.

But it was not just the dedicated training of László Polgár that moved the sisters to the top of the chess world. It was also the advent of the chess database that made new levels of chess study possible. How it came about is described in Susan's book:

Sometime early in 1985 I was invited to play in an exhibition match against the grandmaster John Nunn in Hamburg, Germany.

One of the people I was most excited to see on that trip was Frederic Friedel, who was one of several chess journalists who had come to my defense earlier that year in my disputes with the [Hungarian Chess] Federation. He had also organized the exhibition event with Nunn. I had met him two years before in Budapest at the World Microcomputer Chess Championship, an event in which different chess computers—or “chess engines”—competed against each other. He would have been about forty by our trip to Hamburg, and he had already made a name for himself as a pioneer in applying computer technology to chess.

Frederic invited me and my mother over to his house in Hamburg to give us a sneak peek at his latest project, a digital data-base of chess games he would soon market as ChessBase. Although it might seem elementary in today’s age, the idea of using computer software to organize a searchable collection of chess games was revolutionary back in 1985. Ready access to important games and opening lines is essential to how top-level players train and prepare for tournaments.

Before ChessBase came on the scene, assembling that information was a tedious undertaking. Games had to be copied by hand or clipped from magazines and organized in vast file systems. My father had spent countless hours compiling a collection of hundreds of thousands of games, which he recorded on index cards stored in the long narrow drawers of a giant library card catalog we had in our apartment. Each month, we’d buy two copies of the leading chess publications, like the Russian Shakhmatny Bulletin or the Hungarian Magyar Sakkelet or the Yugoslav Chess Informant, cut out each of the games, paste them to cards, and file them away. Although it took years to build, the system itself was quite fragile. If you return a card to the wrong drawer, you may never find it again. Do that enough, and the system would fall into disarray.

Taking care of our files over the years instilled in me an attention to detail that would serve me well on the chess board. Those card catalogs weren’t very portable, of course. So, when I traveled to tournaments, I always carried several notebooks full of openings and games I had transcribed by hand—as well as any number of chess books—which I’d use to stay fresh in between games, and which we would lug from city to city in big suitcases in the days before suitcases commonly had wheels.

Forty-five years ago: the Polgar family in the 1980: Zsuzsa, Judit and Sofia, with mother Klara and father Lazlo. Behind them the "Kartotek", the index card register boxes which the parents installed. It contained thousands of handwritten games – no ChessBase yet!

ChessBase promised to replace these old analog systems by creating a single, comprehensive game database that, in theory, would be available to anyone with a computer. By today’s standards, the program he showed me that day was dreadfully slow and clunky, as most software was in that era. But the seismic potential of what Frederic had helped build was impossible to deny. Frederic later admitted to me that my father’s system, which he had seen for himself while visiting Budapest, was one of the inspirations for ChessBase.

Frederic was always on the cutting edge of chess computer technology. In fact, it was during a visit to his home sometime later that I first met Matthias Wullenweber, who was already at work on the chess engine Fritz, one of the most sophisticated chess programs of its day. Testing out Fritz at Frederic’s house that day, it was clear that with just a few more breakthroughs, this technology could change the game of chess forever. And I got my first glimpse of this future during my visits to Frederic’s house.

Frederic and Matthias were helping to build a future for chess that just a few years earlier would have been unimaginable. Seeing what they had created filled me with a kind of hope and optimism that I had never felt before.

You can order the Rebel Queen in many book outlets, or on Amazon, where you can also get the Kindle edition. The print edition costs $30, the eBook version is $19.99.