Born to a poor Jewish family in Cold War Budapest, Susan (Hungarian: Zsuzsa) Polgar would emerge as the one of the greatest female chess players the world had ever seen. She became the highest rated female chess player on the planet, and the first woman to qualify for the men's World Chess Championship cycle. She went on to achieve the game's triple crown, holding Womens' World Championship titles in all three major chess time formats (blitz, rapid, and classical).

Before her improbable rise, it was taken for granted that women were incapable of excellence in the game of chess. But the extraordinary training imparted by her father László on his three daughters disproved this notion. In fact Susan's sister Judit became the strongest female chess player in the history of the game, rising at one state to the top ten in the men's (the open) list.

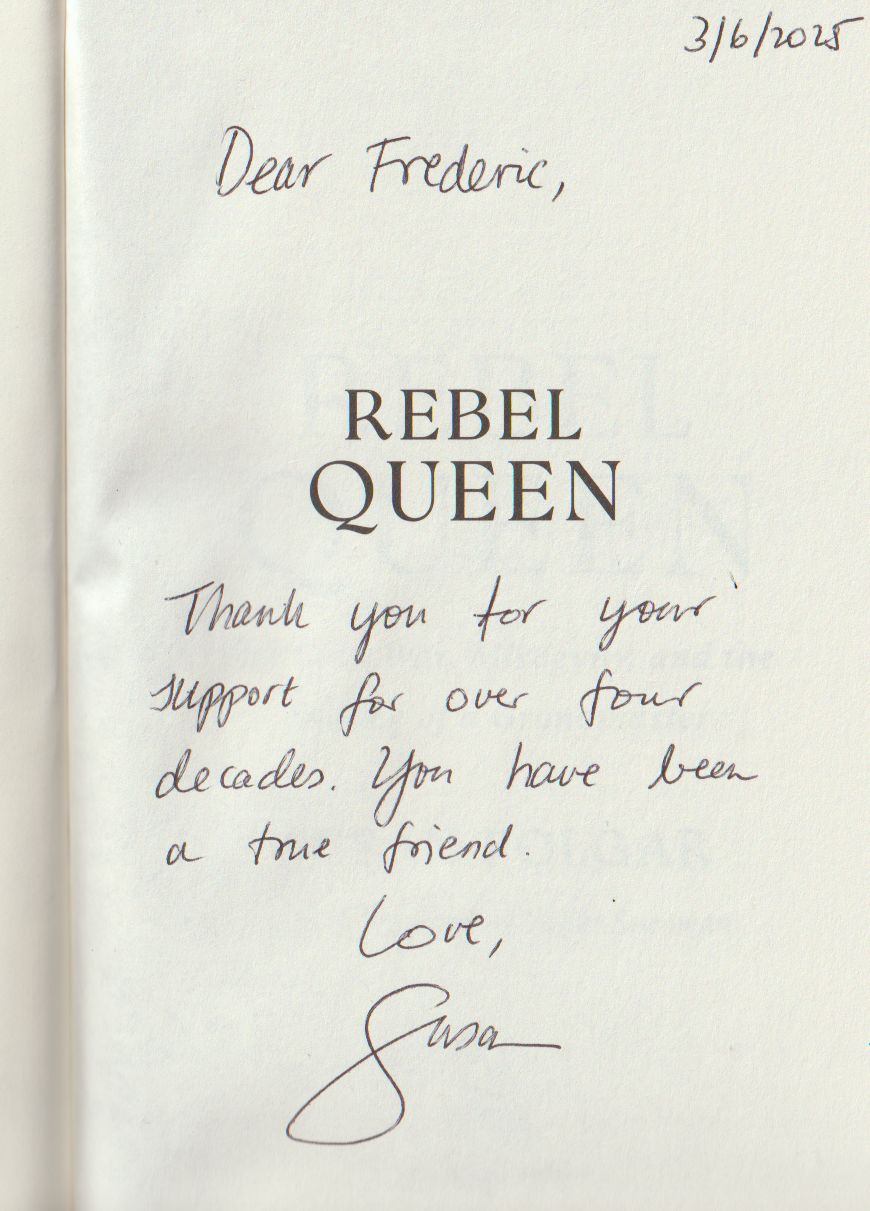

I received a copy of the printed book from Susan at the beginning of the month. I started to read it, but had to compete with my wife, who had known the entire Polgar family from numerous visits to our house. Ingrid went through the entire book before I had finished the first chapters. She thought it was extremely well written, very personal and full of remarkable narration of the life of a chess prodigy.

With permission of Susan and the publishers we present you with some excerpts that will give you an impression of what awaits you in the book.

How I discovered chess

I first discovered chess one afternoon just shy of my fourth birthday. I’ve heard the story so many times I can’t say for certain which parts I actually remember and which have been told to me. My mother was in the kitchen preparing dinner when I made my way to the old beat-up cabinet in our entryway. I knew I wasn’t allowed in there. But tell a three-year-old she can’t have something, and it only makes

Rummaging through the folded linens and old clothes, I wasn’t quite sure what I was looking for until I saw it. A mysterious wooden rectangle with a strange black-and-white pattern—I had no idea what it was, but I was drawn to it. As I pulled it out, the rectangle hinged open into a square, sending a stream of carved figurines tumbling to the floor in a long crackling crash. I knew I was in trouble.

The noise sent my mother rushing into the entryway. She would have been only twenty-six, but had already grown into the role of the Yiddishe Mame—doting and warm much of the time, but a firm enforcer when she needed to be. She found me on the floor, the board and pieces spread out around me. I held up the small horse-shaped carving I had grasped in my hand, proud of the new plaything I had discovered. “Look, Mommy. More toys!”

“That’s not a toy, Zsuzsikam,” her favorite term of affection for me (literally “my little Suzie”).

“That’s a game. But you’ll have to wait for Daddy to come home. He’ll teach you to play.”

Neither of my parents had any real interest in the game before I came along. My mother didn’t even know how to play. My father went through a chess phase as a teenager, but he mainly took up the game to impress a girl (a fact I only recently learned from him). During his first week of high school, an attractive young woman approached him and tried to recruit him to the chess team. It didn’t matter that he had never played, she explained. They would teach him. He signed up on the spot and ended up losing all but his final game that year. After spending his summer studying and playing chess as much as he could, he gradually improved to the point where he could win most of his high school games. His team even made it to the Budapest final in his last year of high school. But he didn’t play much after that.

My Father’s educational theories

By the time I arrived on the scene on April 19, 1969, my father had already developed an elaborate method for fostering brilliance in children from an early age. More than that, my parents had officially decided to make me their first experiment. Not only would I be homeschooled, which was practically unheard-of in Hungary at the time, but my education would focus on a single topic—one they intended to choose for me. As it turned out, they wouldn’t have to.

First visit to a Chess Club

“Are you looking for a game?” one of the players asked my father.

“Not for me, no. For her,” he said, looking down at me.

The men exploded with laughter, which surprised me. What did my dad say that was so funny?

“Yes, really, my daughter wants to play. Can anybody give her a game?”

Most of the men just went back to what they were doing. I imagine they thought my father was just a crazy person, but he didn’t give up. He did a lap around the room, never letting go of my hand, politely asking each player if they wouldn’t mind playing some chess with his little girl.

“I think she’ll surprise you,” he said to one of them. “I know she will.”

Eventually one older man agreed to sit down with me, probably so that my dad would stop asking. This got yet another round of laughter and taunts from the other men. “Oh, you’re going to play the little girl?” one of them remarked to my opponent. “Why, tired of losing to men?”

…I played several games that afternoon from my perch atop two phone books, the details of which I can’t really remember. I know I won a few of them. The thing that stays with me, though, is the reaction I got from the old-timers. Every time I made a good move or avoided some beginner’s trap my opponent had set for me, the crowd would give a little chuckle—not in the dismissive way they had laughed at my father, but out of surprise and approval, like a pat on the back. In those moments, I just felt special and powerful, like a fairy tale queen ready to conquer the world.

Playing Tal in Moscow

In Moscow we visited an international tournament in which Mikhail Tal happened to be competing. I was still quite shy as a thirteen-year-old, and the thought of approaching him was too much for me to bear. Sensing this, my mother intervened. She walked over to Tal while he was pacing in the hallway chain-smoking, as he so often did. She introduced herself as my mother, and explained that it was a dream of mine to play him in a blitz game, if he could find the time. His eyes lit up. He obviously knew who I was. It would be his pleasure, he said.

I got very excited. I could hardly imagine what was about to take place. He disappeared from our sight to resume his tournament game. A short time later he came out, and said, “I am ready for some blitz.” He had offered his tournament opponent a draw just so he could play me.

It didn’t seem real. Tal—one of the greatest players to ever touch a chess piece—had actually heard of me. Even better, he would rather play with me than continue with a far more consequential game in an official event. This just couldn’t be happening. I can only imagine his reasons for sitting down with me. Maybe he was curious about how good I actually was. Or maybe he was just being kind. Probably it was a bit of both.

I can still picture the confident way he moved the pieces, evidence of a lifetime spent at the board; the big-eyed facial expressions he’d make when evaluating a position; and his oddly shaped right hand, which was deformed from birth by a congenital disorder. Based on his playing style, I had imagined his personality might be a bit no-nonsense, or even a little hostile. I was pleased to be proven wrong. The whole time he showed me nothing but warmth and kindness, peppering our games with jokes and funny observations.

As we blitzed out moves in a series of games, a crowd of people swarmed the table, which made me a bit nervous. But anxiety was a small price to pay for spending time with one of my heroes. I couldn’t wait to get back to my chess club in Budapest and tell all of my friends that I had tested my mettle against the great magician himself. Would they even believe me?

I surprised myself in that first game, sacrificing two pieces in Tal-like fashion, and forcing a draw by perpetual check, which prompted an approving smile from the former champion. After that, Tal took over, winning the remaining few games. But I didn’t mind. I was having the time of my life.

Memories of winning first Olympiad Gold

The 1988 Chess Olympiad took place in Thessaloniki, Greece. Until that year, the Hungarian Chess Federation had always found some excuse or other to keep me out of the games. But a lot had changed by 1988. To begin with, my sisters and I were the top female players in Hungary: me in the first spot, followed by Judit, and then Sofia, who was tied for third. So keeping all of us off the Olympiad team would be difficult to justify, even by the tortured logic of the Hungarian chess bureaucracy.

...

For weeks, I had tried not to imagine what it would be like to win in Greece. The moment it was over, though, a tsunami of emotion came rushing into me—a sensation that went beyond happiness or contentment or pride. This was pure joy. I don’t remember another victory meaning so much or feeling so good.

The hours that followed are still mostly a blur in my memory. I can remember posing for pictures with my teammates, struggling to stand still from all of the adrenaline. I especially remember standing on stage during the medal ceremony as the Hungarian flag was raised just a little bit higher than the Soviet flag, our national anthem playing triumphantly. I remember Garry Kasparov’s toothy smile as he congratulated me and encouraged me to “keep it up,” and the tears of joy welled up in my parents’ eyes.

Most moving of all, however, was what awaited us back home in Hungary. As we stepped out of the Budapest airport, a crowd of hundreds greeted us, applauding and holding up homemade signs and chanting our names. We had left Hungary as black sheep and returned as golden girls…

This was the heyday of “Polgaria.” That was the name the press gave to me and my sisters after our gold-medal coup at the 1988 Olympiad, as if we were a nation unto ourselves or a cultural institution like the Beatles or the Rat Pack.

Meeting Bobby

I was twenty-four years old in 1993 when I packed up my VW Passat and headed for the border. My destination: a secret location in Yugoslavia. I had been summoned by an international criminal who was on the run from US authorities. But that’s not how I saw him. To me, he was simply one of the greatest chess players in the history of the game. And if Bobby Fischer wanted to meet me, I wasn’t going to say no.

…I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t surprised by his invitation. I knew that Bobby held female chess players in very low regard. “They’re all weak, all women,” he remarked in a 1961 interview. “They’re stupid compared to men. They shouldn’t play chess, you know. They’re like beginners. They lose every single game against a man.” He even bragged that there wasn’t a woman in the world that he couldn’t beat, even after giving her knight odds.

…We played just one game of Fischer Random that afternoon. And although I was new to this strange chess variant, I played Bobby to a draw. As we were finishing up, there was one question I couldn’t help but ask. “So Bobby,” I said, “do you still believe you can defeat any woman in the world, even giving knight odds?”

“Not anymore,” he said.

Fischer Random

Bobby Fischer and I played countless games of Fischer Random during the time we spent together, typically over dinner while waiting on our orders. Today, the variant is played with a symmetrical setup, in which the back rank of pieces is arranged in the same random way for both players before the game begins. That’s not how we played, though—at least not early on.

Instead, we would begin each game with an empty back rank. Then, we would use our first eight moves to choose for ourselves where on the back rank each piece would start the game. In the end, each player would have a different, nonsymmetrical arrangement of pieces. Without the restriction of symmetry, there can be millions and millions of different starting positions. Bobby used to say with a characteristic chuckle, “I wonder how anyone will be able to analyze and remember all of those openings?”

Bobby asked me never to publish the games we played. Out of respect for him, I turned down multiple offers over the years to compile a book of our games. However, I feel that it is important to give chess fans a glimpse at a few of those games, so that they can get a sense of the process Bobby and I went through in developing the final rules of Fischer Random.

[Here the book describes the highlights of two of the games]

Death threat in Calvia

The day before my first game, I ran into a Hungarian chess fan at the hotel who I recognized from previous Olympiads. It wasn’t a pleasant reunion. He told me how disappointed he was that I had decided to play for the Americans. I had betrayed my home country, he said, and I should be ashamed of myself. When I tried to brush him off, it only enraged him further. “You better hope you don’t get paired with Hungary,” he said. “If you sit down across from any Hungarian player, I promise, you won’t live to see another day.” Then he stormed off.”

I had experienced nearly every form of harassment the chess world could muster by that point in my life. But I had never received a death threat before. I didn’t know what to do. There was no way of knowing if he was serious or not.

I had a serious dilemma on my hands. Even before arriving in Spain, we had discussed the possibility that I might sit out my game against Hungary, provided it was an early round. I knew the game would rub a lot of people the wrong way. It was also a matter of personal pride for me. In all my years playing in the Olympiad, I had never once missed a single game. To do so now, in response to the bullying remarks of some ignorant fan, was painful to even consider.

But I had two young children at home who I was raising by myself. And there was a real chance, however small, that should I play in the next round, they’d be forced to grow up without a mother. This is not to mention the fact that my parents and Judit—all of whom lived in Hungary—might be in danger too. It was an impossible decision.

I called my parents and sisters and filled them in. They all had strong opinions of their own. My father, I remember, firmly believed I should play. But not everyone agreed. After discussing it for a couple of hours, I asked the four of them to vote yes or no. Should I play tomorrow, or sit the game out? They split 2–2. It was up to me.

I gathered my team members and [husband] Paul and announced that I would play—and that my decision was final. I told them to go get a good night’s sleep and be ready to fight tomorrow. That’s when Paul pulled me aside. He expressed how proud he was of my decision, and that he wasn’t going to let anything happen to me. “If they try to come for you,” he said, “they’ll need to go through me first.”

That night, he sat by himself on a chair outside my hotel room door, staying awake until the next morning just to make sure nobody tried anything.