[Note that Jon Speelman also looks at the content of the article in video format, here embedded at the end of the article.]

The recent World Championship appears in hindsight to have been very one-sided, and indeed Magnus Carlsen’s final margin of victory was huge. But the first five games were very close and hard fought, and it was only after the epic sixth game that things changed utterly.

The recent World Championship appears in hindsight to have been very one-sided, and indeed Magnus Carlsen’s final margin of victory was huge. But the first five games were very close and hard fought, and it was only after the epic sixth game that things changed utterly.

The manner of defeat was the worst possible for Ian Nepomniachtchi, and it came at the start of a sequence of three games — which in a match of this intensity is highly unusual and probably just too much. Nepo went into something like shock, and although he was able to operate normally for long tracts of play, his “hand” lost its reliability: which is an awful thing when you have to be able to rely on playing at least sensibly, as decisions have to be made move by move under extreme tension over an extended period.

Nepo’s collapse was dramatic but far from (and here I find myself endangering my life by using the u word) unprecedented. Under match conditions, it’s not unusual for players to crack either totally or for a few games. And in this case, it brought them to the end of the match — which at 14 games was long by today’s standards — but short compared to the battles of the past.

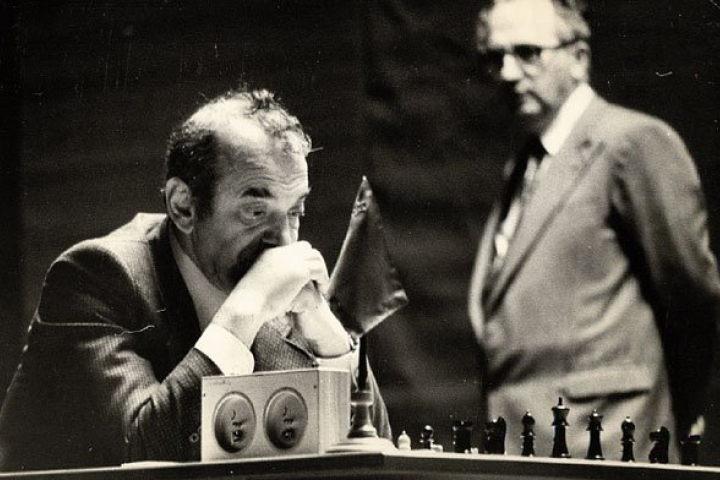

[Photo: Niki Riga]

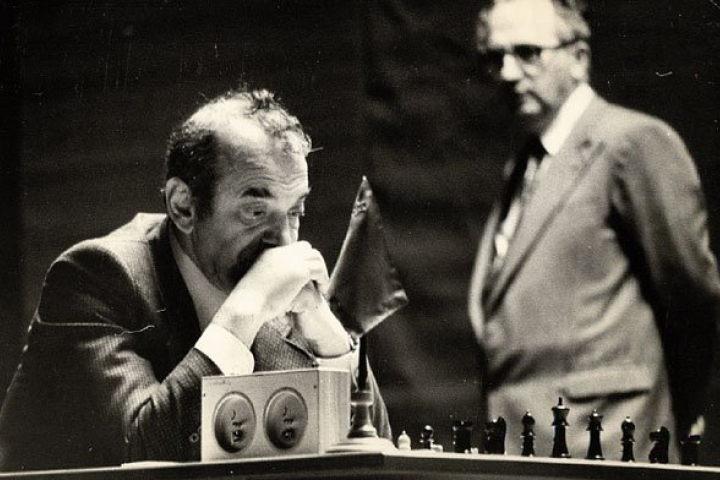

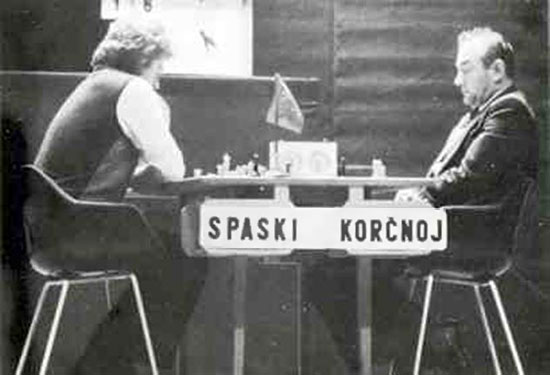

Thinking about collapses I went back to the famous battle between Viktor Korchnoi and Boris Spassky in Belgrade 1977, and found Ray Keene’s book on it on my shelves.

“Only” the Candidates final, this was nevertheless scheduled for 20 games, and in intensity, bad feeling and shenanigans, acted as a precursor to the Karpov v Korchnoi World Championship in Baguio 1978.

Having defected from the USSR in 1976, Korchnoi at that stage was a “non-person” whose games they didn’t publish (at least not with his name attached). Spassky not only faced a formidable opponent but also had the weight of his country’s expectations upon him (as he did later against Fischer), and in the first nine games Korchnoi built up a massive lead of 6½-2½.

It was in game 10 that Spassky began to behave very strangely. Both players had a private box where they could relax when it was not their move, but Spassky began to stay there during his moves as well, returning to the board only to move the pieces. Korchnoi won game 10 despite having a losing position at one stage, but as protests and counterprotests erupted regarding the box, Spassky, who at one stage took to appearing on the stage in a visor, won four in a row from 11-14. Eventually the positions of the two boxes were reversed so that Korchnoi could at least see his opponent when he was in his “half-open box”. And after draws in games 15 and 16, Korchnoi won the last two to finish as the 10½-7½ winner with two games remaining.

I hope I’ve given a reasonable account of this. The exact details of every protest, counterprotest and statement by the chief arbiter Bozidar Kazic and FIDE President Max Euwe don’t seem too important at this distance, but the general feeling is that match play is intense and brutal and feelings can run very high, even when international politics aren’t involved. (Indeed, this time some of the comments about Daniil Dubov’s decision to continue to work for Magnus Carlsen against a fellow Russian have been highly intemperate.)

As to the actual games in Belgrade, they were fought to the hilt. The most famous is the back rank battle in game 7, and I've included a couple more as well.

My next column will be on January 2nd 2022 and will presumably have at least some elements of retrospection, and also prognostication.

In the meantime a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to all.

Select an entry from the list to switch between games