[Note that Jon Speelman also looks at the content of the article in video format, here embedded at the end of the article.]

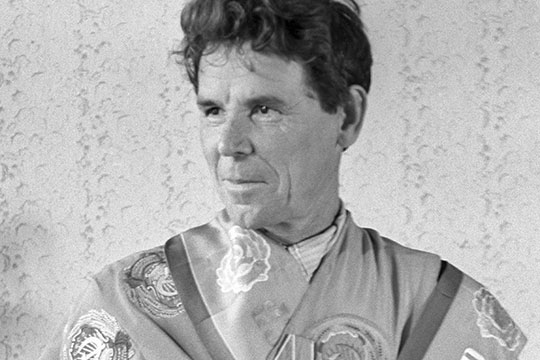

In the last two columns we’ve indulged in extreme violence with some of my favourite “hacks”. We'll certainly return to this theme at some stage, perhaps with some games by the wonderful Rashid Nezhmetdinov: a player so violent that he was able more than once to out-hack Misha Tal himself.

But man and chess player cannot live by violence alone, and even Tal played some positional games including an archetypical pawn endgame that I remember from Peter Clarke’s book on him. This game (below v Bozidar Djurasevic) featured a race between competing pawn majorities, but perhaps the greatest contrast with violent tactics (though tactics may sometimes precede it) is seen in the preternatural stillness of zugzwang.

Zugzwang is the main feature of some games like Othello and also extremely prominent in draughts which (I presume the 10x10 version) Nezhmetdinov played to a very high standard as well. In chess, it is very unusual until the endgame but underpins much of endgame theory. For example, were it not for the obligation to move then almost all endgames with rook and pawn v rook would be drawn since the defender could give up the rook for the pawn and then with K v K+R sit shtum at the critical moment — and the opposition would cease to have any meaning.

As it is, zugzwang is the path to victory in many endgames and I’ve got a few examples, of it and “pseudo-zugzwang” — manoeuvring to give the opponent the move in a position where he or she may have a decent choice but will have to work very hard to find it. Sometimes you don’t know yourself whether it’s pseudo or real but putting pressure on the opponent is sufficient reason to try.

We start with the Tal pawn endgame — which turns out actually to be drawn if Black defends correctly and then move on to a couple of pawn endings in which the critical point is that one or other king is denied a crucial square which means that his opposite number can outmanoeuvre him. Then there are a couple of studies — the first of them a theoretical rook ending, followed by three examples of zugzwang, pseudo or otherwise, from my own games.

Rashid Nezhmetdinov | Photo: S. Tokarev