Our

regular contributor, FM Steve Giddins from England, is known to ChessBase readers

as a tournament reporter, writer and Russian translator. But he also has a secret

side: he is huge fan of chess problems.

Our

regular contributor, FM Steve Giddins from England, is known to ChessBase readers

as a tournament reporter, writer and Russian translator. But he also has a secret

side: he is huge fan of chess problems.

Having spent most of his chess life ignoring problems almost entirely, he became

converted to the problem world a few years ago, thanks largely to a chance encounter

with some visiting problem-enthusiasts, whilst Steve was living in Moscow. Now

he sees it as his mission to convert other OTB players to the joys of chess

problems.

In a new series of fortnightly articles, Steve will take you on a journey into

this fascinating world, introducing you to the beautiful ideas and compositions

to be found there, and stripping away the mysteries of the problemists' terminology.

In the first of his articles, he looks at some classical direct-mates.

Bringing back checkmate

By Steve Giddins

Ask even a non-chessplayer what the object of the game of chess is, and he

or she will tell you: checkmate. But be honest, now: how often do we actually

see a king checkmated in a game of chess? Even at amateur levals, not very often,

and at GM level, hardly ever. And if we do, it is more often than not a crude

back-rank mate, or Qxg7, mating a king on g8, while all the other white pieces

stand idle, elsewhere on the board. Not very aesthetic, is it? Yet there is

a branch of chess where mate occurs all the time, in virtually every position.

And not only that, many of those mates are exceptionally beautiful, surprising

mates, where all the pieces on the board take part and no superfluous force

stands idly by. I am talking, of course, of problem chess.

It is one of the great tragedies of our game that so many OTB players take

little or no notice of chess problems. It is a tragedy because problems are

remarkably beautiful, and, as a chess player, you are uniquely qualified to

appreciate them. You may love other art forms, such as music or painting, but

unless you have at least some specialist musical or artistic training, you are

always going to be missing some of the beauty and skill in what you are listening

to or looking at. But if you play chess, and understand what the chess pieces

can do, you have all the training you need to appreciate fully a fine chess

problem.

Take the following example:

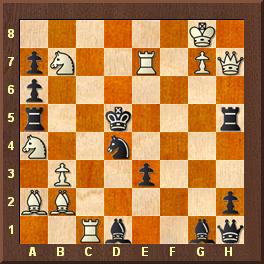

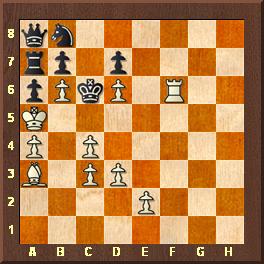

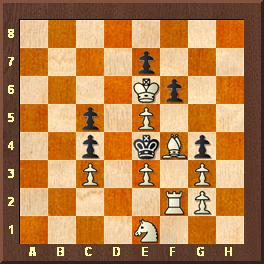

Godfrey Heathcote, 1st Prize,

Hampstead and Highgate Express, 1905

Mate in two

The first thing to say is: don't worry if the position does not look like it

arose in a game. It didn't – so why should it look like it did? That is like

objecting to an abstract painting on the grounds that "it doesn't look

like what it says it is". As Nimzowitsch famously said in response to Dr

Tarrasch, "the beauty of a chess move lies in the thought behind it".

That is certainly true of chess problems.

What you are looking at here is actually one of the most famous chess problems

ever. It is one of the first examples of what is known as a task problem.

As every decent chessplayer knows, a knight in the centre of the board has a

maximum of eight possible moves. In the present case, that is true of the black

knight on d4. This problem shows all eight moves of the black knight (the knight

wheel) as part of the solution.

White's first move (the key) is 1.Rcc7 The threat is 2.Nc3

mate. Black can defend this by moving his knight, so as to free the d4-square

for his king. However, as we see, every one of the knight's eight possible moves

has a fatal drawback:

1...Nc2 (blocks the line of Bd1) 2.b4#

1...Nxb3 (self-pins the knight) 2.Qd3#;

1...Nb5 (blocks the Ra5) 2.Rc5#;

1...Nc6 (self-blocks the square c6) 2.Rcd7#;

1...Ne6 (self-blocks the square e6) 2.Red7#;

1...Nf5 (blocks the line of the Rh5) 2.Re5#;

1...Nf3 (blocks the line of the Qh1) 2.Qe4#;

1...Ne2 (blocks the line of the Bd1) 2.Qxh5#

Is that not wonderful? If you will stick with me over the succeeding months,

I will aim to present you many, many more examples of such chessboard beauty,

and introduce you to this wonderful world of chess problem composition.

In a direct mate problem, as I hope everybody knows, White is to play,

and must mate Black, by force, in no longer than the stipulated number of moves,

and in a single, unique manner. Naturally, the more squares (flights)

the black king has in the starting position, the harder it will usually be to

mate him. Take the following example:

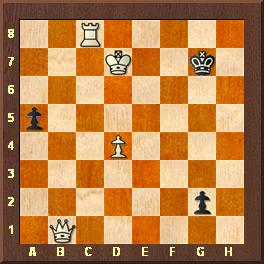

William A Shinkman - Checkmate December 1901

Mate in three

At present, the BK has three flights on f7, f6 and h6. An

OTB player, looking to mate Black as soon as possible and escape down the pub,

would probably look for a key which takes some squares away from the king. But

problem composers are generous chaps, and Shinkman on this occasion was obviously

aware of the dictum that "it is better to give than to receive". He

provided a key which not only fails to take any flights away from the BK, but

actually gives him no fewer than five (!) additional flights, bringing his complement

up to the maximum eight:

1.Rc2. Sadly for Black, it does him no good. After 1...g1Q 2.Qxg1+

and mate next move, whilst if he instead moves the king anywhere,, then

2.Rxg2 and mate next move.

When it comes to flights, composers always try to avoid having a flight-taking

key. A key which takes one flight but gives another (a give and take key)

is acceptable, but flight-giving keys are prized most of all.

As well as giving flights, another thing one would not generally expect a problem

key to do is to expose the white king to checks, especially in a two-mover.

After all, if we have only two moves to checkmate Black, and our first move

allows him to check us, it is going to be pretty hard to mate him on the next

move, isn't it? Well, yes and no…

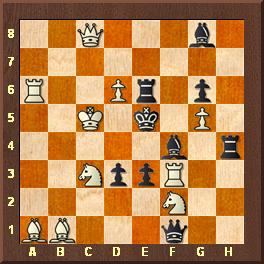

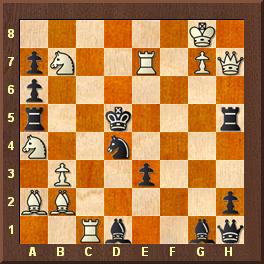

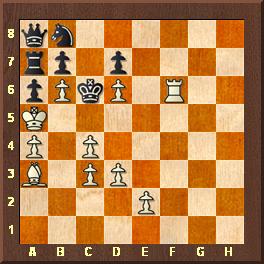

Norman A Macleod - 5th pr. Yug. Chess Fed Ty 1950

Mate in two

The remarkable key of this problem is 1.Kc4. This threatens 2.Qc5 mate,

and if 1…Kf5 there is 2.Ra5 mate, exploiting two pins, on the Re6 and Bf4. However,

as you will observe, White's first move has exposed the white king to checks

along three different lines – the g8-a2 diagonal, f1-a6 diagonal, and along

the fourth rank. But panic not, my friends – each of the possible discovered

checks opens a white guard of the flight on f5, which allows White to meet check

with check (a crosscheck) and mate:

1...Re6-moves+ 2.Nd5# ;

1...Bf4-moves+ 2.Nce4#;

1...d2+ 2.Ne2#

Not the least remarkable thing about this problem is that it was composed in

about 15 minutes (!), during a train journey the composer was taking, with the

OTB International Master and many-times champion of Scotland, W A Fairhurst.

If you like economical mates, and spectacular key moves, then you have already

seen a few, and there are plenty of delights to come over succeeding months,

especially in the problems of the so-called Bohemian School, which was popular

in the 19th and early 20th centuries. But strategy is also another feature of

many problems. Here is a delightfully simple example of a paradoxical idea:

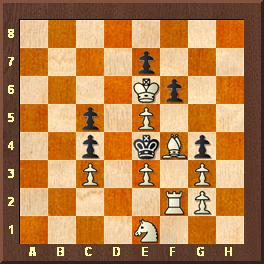

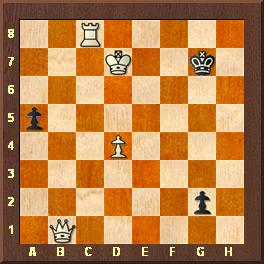

Matti Myllyniemi, 1st Prize Suomen Shakki 1952

Mate in three

The first thing that strikes one about this position is how few moves Black

has – only two, in fact. In such problems, it is always worth starting by looking

to see whether mates are already provided against these (so-called set plays).

In this case, we soon see that this is the case: 1...fxe5 2.Re2 forces 2…exf4

3.exf4 mate, whilst 1...f5 2.Rf3 forces 2…gxf3 3 gxf3 mate. So all White needs

to do is find a waiting move, which does not upset anything. Sadly, he does

not have one, so he is forced to find another idea.

The key is 1.Bh6. This leaves Black with the same two legal moves, but

look what happens when we examine them. After 1...fxe5, we find that

2.Re2 is no longer possible because of stalemate, but instead 2.Rf3 now

mates after 2…gxf3 3.gxf3 mate. Likewise, after 1…f5, the move

2.Rf3, which worked before, fails to 2…f4, but instead 2 Re2 forces

2…f4 3.exf4 mate!

It is worth looking again at what has happened here. In the set play phase,

1…fxe5 was met by 2.Re2 and 1…f5 by 2.Rf3, but in the post-key phase,

the White second moves are reversed. This beautiful and paradoxical effect is

known as reciprocal change.

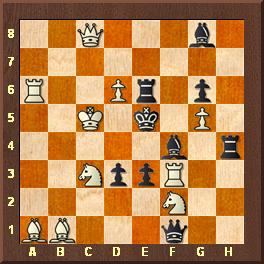

Strategy comes especially to the fore in longer problems, many of which feature

what is known as a pendulum manoeuvre. Here we have a bit of a monster,

a mate in no fewer than 17 moves:

Yakov Vladimirov 1st Pr, Macleod Memorial 1993-4

Mate in 17

White's basic mating idea is simple enough – Rf8 and Rc8 mate. The trouble

is, if he plays it at once, 1.Rf8 is stalemate. If his bishop were on g1, and

his e-pawn on e5, then he could use discovered check to get his rook to f8 with

tempo, by playing 1.Rf2 Kc5 2.Rf8+ etc. So, he embarks on a long manoeuvre to

achieve just this.

1.Bc1 Kc5 2.Be3+. Note that White must check every time the BK comes

to c5, since otherwise Black breaks his bonds with Nc6+. 2...Kc6 3.Bf4 Kc5

4.Rf5+ Kc6 5.Be5 Kc5 6.Bh2+ Kc6 7.Rf6 Kc5 8.Bg1+ Kc6 9.e3 Kc5 10.e4+ Kc6 11.Bh2

Kc5 12.Rf5+ Kc6 13.e5 Kc5 14.Bg1+ Kc6. Mission accomplished! 15.Rf2 Kc5

16.Rf8+ Kc6 17.Rc8#.

Well, that is the end of our first instalment. In our next piece, in a couple

of weeks' time, we will look at some of the alternative types of chess problem,

such as helpmates and selfmates.

Our

regular contributor, FM Steve Giddins from England, is known to ChessBase readers

as a tournament reporter, writer and Russian translator. But he also has a secret

side: he is huge fan of chess problems.

Our

regular contributor, FM Steve Giddins from England, is known to ChessBase readers

as a tournament reporter, writer and Russian translator. But he also has a secret

side: he is huge fan of chess problems.