Unsolved Chess Mysteries

By Edward Winter

Fischer-Karpov photograph (C.N. 3588)

First, a deceptively simple-looking matter. There follows, from pages 161-162

of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1991), a description of the mid-1970s

discussions between Fischer and Karpov on a possible world championship match:

‘After the talks we set out for a stroll around Tokyo. I was afraid

that autograph hounds would harass us, but, to my amazement, not one person

approached us. Here were two of the best chessplayers in modern times, whose

photographs practically never left the front page, walking down the street

– you’d think at least someone would have noticed. Later I understood

that such a thing is possible in only one place on earth: Tokyo.

One photograph – the only one in which Fischer and I are together

– was taken. The chairman of the Japanese Chess Federation, Matsumoto,

ingratiated himself with Fischer, who disliked journalists even more than

their articles, and took our picture “for his family album”. A

few days later the shot was sold to Agence France-Presse, who in turn distributed

it worldwide.’

The reference to worldwide distribution suggests that the photograph of Fischer

and Karpov should be commonplace, but who knows where it has been published?

Bronstein v Goldenov (C.N. 4762)

Shortly after David Bronstein’s death in 2006 Pierre Bourget (Canada)

mentioned the game D. Bronstein v B. Goldenov, Kiev, 1944, which is given in

various databases as follows: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Bb4 5 e5 h6 6

Bd2 Bxc3 7 bxc3 Ne4 8 Qg4 g6 9 Bc1 c5 10 Bd3 cxd4 11 Ne2 Nc5 12 cxd4 Nxd3+ 13

cxd3 b6 14 h4 h5 15 Qf3 Nc6 16 Bg5 Ne7 17 O-O Ba6 18 Rac1 Qd7 19 Qf6 Rg8 20

Rc3 Nf5 21 Ng3 Nxd4 22 Rfc1 Nb5 23 R3c2 Qd8 24 Qf4 Qd7 25 a4 Resigns.

However, Mr Bourget pointed out that this game has appeared elsewhere, and

most notably in the later editions of The Golden Treasury of Chess by

F. Wellmuth/I.A. Horowitz, as ending on move 24 with, in the words of that book,

‘one of the most amazing winning moves on record’:

24 Rc8.

The Treasury gave the move three exclamation marks, but what is the

truth about the conclusion to the game?

‘Garry Kaspartov’ (C.N. 4150)

In C.N. 4150 Miquel Artigas (Spain) drew attention to a 128-page book in Spanish

published in 1999 by Ediciones Altosa with a hitherto unknown chess author on

the front cover: ‘Garry Kaspartov’. Noting that the book was badly

written, technically weak and old-fashioned, our correspondent quoted the following

examples in an attempt to help identify the origins of the text:

Capítulo III. Regla 3ª (page 29): “Si se ha empezado una partida

con una pieza de menos habiéndose efectuado la cuarta jugada de ambas partes,

será obligatorio acabar la partida sin poder colocar la pieza olvidada en

su lugar correspondiente.” [If a game has been begun with a piece

missing and both players have made their fourth moves, it shall be obligatory

to complete the game without being able to put the forgotten piece at its

appropriate place.]

Regla 17ª (page 32): “El que da de ventaja una torre, puede igualmente

enrocar del lado en que falta esta torre diciendo: enroco.” [The

player giving the odds of a rook may also castle on the side where this rook

has been removed, saying: I castle.]

Capítulo XVI. Consejos (page 121): “Tenemos que procurar hacer el

enroque lo antes posible y siempre antes de las ocho primeras jugadas, siendo

este síntoma ideal.” [We must manage to castle as early as possible

and always within the first eight moves, this being the ideal method.]

Who was responsible for bringing out such a book and using the misleading name

‘Kaspartov’? The text bears no resemblance to any known writing

by Garry Kasparov. In a subsequent C.N. item we mentioned that the only master

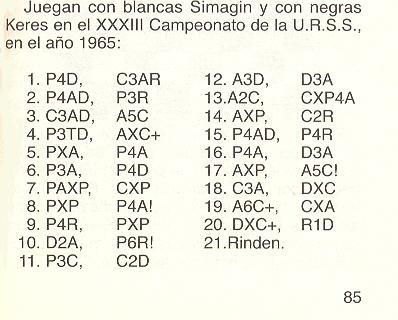

game presented in the book was the following:

The above victory by Keres in the 1965 USSR Championship was, in fact, against

Kuzmin, not Simagin. Is that perhaps a helpful clue as to the provenance of

the Spanish volume? Have any other books made the same factual mistake?

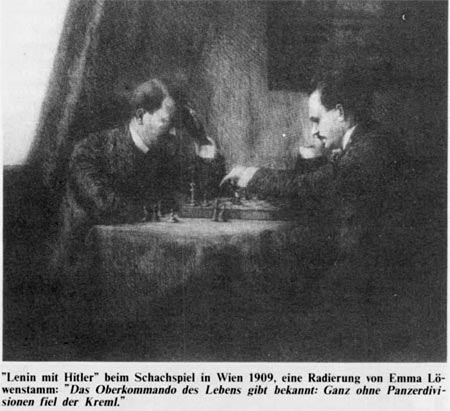

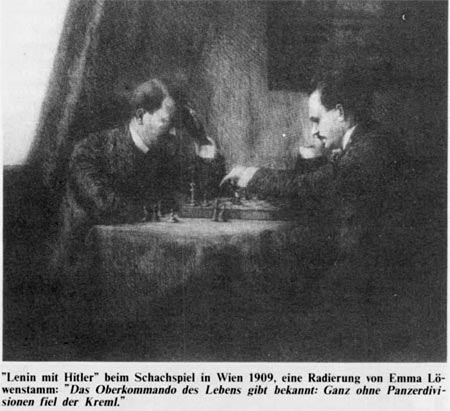

Hitler and Lenin (C.N. 4055)

Finally in the present selection, there is the alleged picture of Hitler playing

chess against Lenin:

Raising this topic in Chess Notes, Edward Hamelrath (Germany) wrote:

‘This etching comes from the extreme right-wing (and now defunct)

magazine Europa Vorn (spezial Nr. 1/4. Quartal 1991), in an article

entitled “Ungeist aus der Flasche” by a “v. Freisaß”.

The article is just a rambling diatribe on twentieth-century world politics

and makes no reference to the picture itself. It is not even clear exactly

what the title is – either “Lenin mit Hitler” or “‘Lenin

mit Hitler’ beim Schachspiel in Wien 1909”. (The “Das Oberkommando

...” comment under the picture was simply plucked out of the text.)

In any case, the Hitler figure corresponds more to his appearance in the mid-1920s

than in 1909.’

Such a picture should, of course, be viewed with extreme circumspection, but

what more can be discovered? All we can add at present is a reference to Hitler

having possibly played chess with Lenin in Vienna in 1909 which appeared on

page 188 of Persönlichkeiten und das Schachspiel by B. Rüegsegger (Huttwil,

2000):

‘Die jüdische Malerin Emma Löwenstamm (1879-1941) brachte in Wien

Hitler und Lenin zusammen, um sie gemeinsam zu malen. Sie lud beide ins Atelier

von Julius von Ludassy ein. Im Donau-Kurier Ingoldstadt vom 19. July

1984 erwähnt Bernd Kallina in seinem Artikel die damals angefertige Zeichnung,

wo Lenin auf der Rückseite die Worte “Lenin mit Hitler” hingeschrieben

haben soll.’

Weiter wird erwähnt, dass sich beide 1909 in Wien getroffen und zusammen

Schach gespielt haben.’

Submit information

or suggestions on chess mysteries

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around

5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around

5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing

in its archives

will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes

and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from

around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary

readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent

masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess

History Center.

Edward

Winter is the editor of

Edward

Winter is the editor of