Man vs. Machine – The Endless Fascination

By Ram Prasad

"In certain kinds of positions, the computer sees

so deeply that it plays like God.”

-- Gary Kasparov

Last February, Garry Kasparov was asked by a Pravda journalist if a new match

against a computer was part of his plans. “I would love to play again,

but it is hard to organize,” Garry said. “You need global publicity

and a big computer – it is very complicated, because I am not just going

to play and collect the money – I want a big “splash.”

Next week, Garry is getting his big splash, when he takes on X3D Fritz.

Indeed, it will be a very big splash with articles and coverage in 1000s of

newspapers and websites.

Let’s use this opportunity to look back specifically at matches where

super-strong GM’s have taken on super-strong computer programs –

a retrospective of sorts. Since this material has been covered extensively

in the past, let’s look at the highlights focussing on the human interest

aspect of the man versus machine encounters of the past that lead up to the

present X3D encounter. For us, the underlying question is: why are these Man

vs. Machine matches endlessly fascinating?

1989: Deep Thought vs. Garry Kasparov

"I think the computer needs to be taught something

– how to resign!"

– Garry Kasparov

Our story begins fourteen years ago, in 1989 – even though Alan Turing

and his ideas for chess-playing computers had been around since four decades

earlier. It begins with Shelby Lyman having an audacious idea. Lyman was a

TV personality who was also a chess promoter in New York. He had been a TV

commentator for the 1987 World Chess Championships, and his statement –

“Chess is a game of ideas” – was quoted often.

As all of us know, in 1989 Garry was also the unquestionable king of chess

– hardly any room for argument there.

At

that time, Feng-Hsuing Hsu, a grad student originally from Taiwan, was pursuing

his Ph.D. in Carnegie Mellon University. Hsu’s topic of choice for his

thesis was to build a very advanced chess-playing computer. His program ran

on linked processors in parallel, and had been named Deep Thought. (Incidentally,

this started the trend of using the prefix “deep” to denote parallel

processors.) Deep Thought and its evaluation algorithms were the subject discussed

in many ACM gatherings. In the computer chess world, Deep Thought was a giant.

At

that time, Feng-Hsuing Hsu, a grad student originally from Taiwan, was pursuing

his Ph.D. in Carnegie Mellon University. Hsu’s topic of choice for his

thesis was to build a very advanced chess-playing computer. His program ran

on linked processors in parallel, and had been named Deep Thought. (Incidentally,

this started the trend of using the prefix “deep” to denote parallel

processors.) Deep Thought and its evaluation algorithms were the subject discussed

in many ACM gatherings. In the computer chess world, Deep Thought was a giant.

Shelby Lyman’s idea was to pit the two giants against each other and

watch the fireworks. He asked Garry Kasparov if he wanted to take on Deep Thought

for a $10,000 purse. Garry being Garry said yes, and a match was on.

A mega-chess event was announced and for the first time since Fischer vs.

Spassky 17 years earlier, chess was in the front pages of American media. Fittingly,

the Big Apple seems to be the venue for many of the Superman vs. super-machine

matches. The question for us is to wonder why, even in the minds of the non-chess-playing

crowd, this match had lit a fire?

Deep Thought was made out to be a cold number-crunching beast. It was to run

on three Sun workstations with linked dual-processors so that the analysis

could be carried out in parallel. The stated speed was close to ¾ million

positions per second per dual-processor. In comparison, the number given for

Garry was three positions per second.

The media slanted the event into a match to salvage the pride of the human

race. Chess was again featured prominently in the American media. From USA

Today to Omni to The Sports Illustrated, every magazine had a buzz going about

the upcoming Man vs. Machine encounter.

The match was a two-game G/90 match at the New York Academy of Fine Arts in

NYC. The actual encounter was a bit of a let down. The machine was no match.

Garry played quietly in the first game and still won. In the second game, he

crushed Deep Thought tactically. Of course, computer chess was still in its

infancy, and there were many reasons given include a “castling bug,”

a very short opening book, and other problems in the transfer and sharing of

the analysis between the linked processors.

After his win in Game 2, presumably because he had saved the pride of humanity,

an enthusiastic (and relieved) audience gave him a standing ovation. In the

post-tournament conference, Garry made a comment half in jest, which summarizes

that match. "I think the computer needs to be taught something –

how to resign!"

The next match wouldn’t be scheduled for a few years, but the Man vs.

Machine race had begun in earnest.

1994: Intel World Chess Express Challenge

In

the early to mid-nineties, chess-playing software were evolving into commercially-sold

entities. Fritz, Rebel and Genius started to take shape. Inevitably, this led

to a revived interest in Man vs. Machine matches.

In

the early to mid-nineties, chess-playing software were evolving into commercially-sold

entities. Fritz, Rebel and Genius started to take shape. Inevitably, this led

to a revived interest in Man vs. Machine matches.

In the first half of 1994 Intel staged what was possibly the strongest blitz

tournament of all times.17 GMs with an Elo average of 2625, an one computer

running Fritz 3, played a round robin blitz tournament in Munich, Germany.

The hardware was an Olivetti with the latest Intel processor, a Pentium 90

MHz, one of only three such powerful machines in Europe. To everyone's surprise

Fritz beat GMs Chernin, Anand, Cvitan, Gelfand, Wojtkiewicz, Hjartarson, Kasparov,

Kramnik and Short (in that order) to finish equal first with Kasparov. In the

playoff a very determined Kasparov demolised the machine 4:1.

1995: Two Kasparov vs. Machine Events

1995 was a busy year for Garry Kasparov. He played two matches against computers.

And sandwiched in between the two, he played the PCA World Championship match

against Vishy Anand and won convincingly.

Versus Genius in Cologne

Revenge was on Garry’s mind when he played his first computer match

against Genius in Cologne. The previous year, in 1994, Genius, a computer program

developed by Richard Lang of the UK, had defeated the world champion. This

had been at the Intel Professional Chess Association Grand Prix in London.

Kasparov had played Genius in a 2-game match, lost and had been eliminated.

But the Grand Prix was a rapid game encounter (25 minutes per player per game).

So Garry came to the 1995 match hoping to avenge the previous year’s

defeat. It was a two-game match. Kasparov started off with White and opened

1.c4. Genius turned it into a QGD Slav defense. This game is a wonderful illustration

of how a Grandmaster can slowly but surely beat a computer. Move by move, Garry

gained the initiative and Genius lost the game. He drew dutifully with Black

and won the match. He had gotten his revenge.

Versus Fritz in London

Kasparov’s second match against a computer that year was with Fritz4

in London. With the Black pieces, Garry went into a Classical Nimzo-Indian

battle. He got a R-B-pawns versus R-N-pawns ending. He traded off his Bishop

for Fritz’ Knight. Then he played a very skillful endgame to win with

black. In the second game, when the computer had Black, it chose to go into

the Tarrasch Defense. Garry simplified into an ending with opposite colored

bishops, he got his draw and won the match.

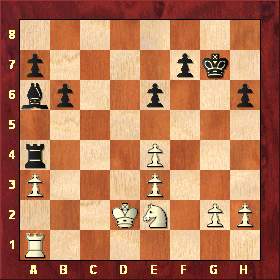

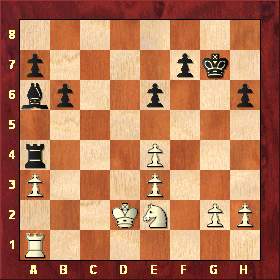

Comp Pentium Fritz4 - Kasparov,G (2795) [E32]

London m London (1), 1995

Position after Fritz played 24.Ra1. Garry exchanged his Bishop for the Knight

and went on to win: 42.Rxf5 a4 43.Rxh5 a3 44.Ra5 a2 45.h5 Rh1 46.Ke4

a1Q 0-1.

1996: Deep Blue vs. Garry Kasparov

"I could feel a new kind of intelligence across

the table."

– Gary Kasparov

Meanwhile, the little program developed by Feng-Hsuing Hsu that had once

been called ChipTest and later Deep Thought, had grown really big. After finishing

his Ph.D., Hsu and his co-programmer Murray Campbell had joined IBM. Now, there

was a whole team working full-time on their chess-playing and program with

specially designed chips. The program had been renamed to Deep Blue by then.

Garry was to take on that program for six games in Philadelphia. The match

was organized by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) to mark the

50th anniversary of the first computer ever. In contrast to his 1989 encounter,

the prize money was a now a whopping $400,000.

In the first game, Deep Blue played the Alapin variation of Sicilian and

managed to defeat Garry. That got the media in an uproar. DB was rated 2650

at the time. But in the second game, Garry played a wonderful Q+B+pawns endgame.

It took him 73 moves to do so, but he managed to subdue the blue beast and

equalize.

The next two games were drawn. Kasparov later claimed that he had to switch

strategies mid match in order to beat DB. "My overall thrust was to avoid

giving the computer any concrete goal to calculate toward," he said, which

could very well be one definition of anti-computer chess. He then proceeded

to win games 5 and 6, and wrapped up the match nicely to collect his prize

check.

| Philadelphia 1996 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Final |

| Kasparov |

0 |

1 |

½

|

½

|

1 |

1 |

4 |

| Deep Blue |

1 |

0 |

½

|

½

|

0 |

0 |

2 |

In the post-match press conference, he amended his opinion a little. "So,

although I did see some signs of intelligence, it's a weird kind, an inefficient,

inflexible kind that makes me think I have a few years left." Unfortunately

for Garry, in just one year his prophesy was to turn out wrong.

1996: Fritz vs. Anatoly Karpov

While

everyone remembers Kasparov vs. Deep Blue, there was another big man vs. machine

event that went unnoticed by comparison. But the true computer-chess fans still

remember AEGON 1996 – organized in the Hague – with fifty strong

chess programs being paired with 50 strong GMs and IMs.

While

everyone remembers Kasparov vs. Deep Blue, there was another big man vs. machine

event that went unnoticed by comparison. But the true computer-chess fans still

remember AEGON 1996 – organized in the Hague – with fifty strong

chess programs being paired with 50 strong GMs and IMs.

One notable encounter from that event was the 2-game match-up between Karpov

and. Fritz. In the first game, Fritz had the black pieces and it chose to go

into a QGD Tarrasch. With the white pieces, Karpov was once again the old wily

Anatoly. He tricked Fritz into giving up a little here, and a little more initiative

there. He then simplified and took Fritz to an endgame, which he then won rather

easily. In the second game, Karpov chose the French defense and held on to

draw and won the match.

1997 Deep Blue vs Gary Kasparov: The Rematch

“What we have is the world's best chess player vs.

Garry Kasparov.”

– IBM CEO Lou Gerstner, when asked why the match got so much attention

This match – the rematch – is the only loss by a superGM to a

super-chess computer. So much has already been said by folks who are way more

qualified to comment on this. Several books have been written about the rematch,

including one released by Feng-Hsuing Hsu this year titled “Behind Deep

Blue.”

Instead of rehashing old ground that is all-too-familiar to many, let’s

look at something else. IM Malcolm Pein may have hit upon what was a crucial

lapse on Garry’s part. When commenting about the “Brains in Bahrain”

match in 2002, he said: Of course one important difference between this match

and the Deep Blue match is that the program cannot be changed between games

– something I cannot believe Kasparov neglected to negotiate in 1997.

| New York 1997 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Final |

| Deep Blue |

0 |

1 |

½

|

½

|

½

|

1 |

3.5 |

| Kasparov |

1 |

0 |

½

|

½

|

½

|

0 |

2.5 |

No mention of the 1997 rematch will be complete without discussing Game 2.

Garry offered up material (two pawns) to Deep Blue. But the machine refused

Garry’s offer and instead played for a better position. While it was

making a move every three minutes consistently, at that point it went into

a 15-minute think before declining the material proffered by Kasparov. There

has been endless speculation as to whether there was any human intervention.

To make matters worse, it turned out that Garry had resigned too early. Later,

some folks used their computers to discover a way by which Garry could have

drawn.

Arguably the definitive

article of a behind-the-scenes look by an insider was written by his

computer consultant Frederic Friedel. (Don’t miss Frederic’s fascinating

account of how Garry handled this news.)

In short, the consensus is that it was Game 2 that did Garry in. If DB had

dished out a tactical mega-blow, Garry could have handled that. He would have

taken it on the chin and come back to dish one back to the blue monster. But

the thing was, DB had made a prophylactic move. It had landed a fragile blow,

and it seemed that for the rest of the match Garry just couldn’t cope

with that. He mixed up the sequence of moves in Game 6 and lost quickly.

Deep Blue had won 3.5-2.5. What was frustrating to Garry and to a lot of chess

fans was that after getting its win, IBM outright dismissed the very notion

of any more rematches.

1998: Rebel vs Vishy Anand 0.5-1.5

“Anti-grandmaster style is about having the initiative.

Don't lose it. It is important.”

– Rebel programmer Ed Schroder.

In the natural progression of man vs machine matches, we next saw Game Theory

in its truest sense. Even as GM’s were getting savvier in their play

against computers, (steering the game towards positional chess as opposed to

tactical, to put it simplistically) the computer programmers were doing the

exact opposite. This led to the so-called “anti-grandmaster” chess,

which culminated in the program Rebel being programmed and readied

for months specifically to face GM Anand in 1998.

In the natural progression of man vs machine matches, we next saw Game Theory

in its truest sense. Even as GM’s were getting savvier in their play

against computers, (steering the game towards positional chess as opposed to

tactical, to put it simplistically) the computer programmers were doing the

exact opposite. This led to the so-called “anti-grandmaster” chess,

which culminated in the program Rebel being programmed and readied

for months specifically to face GM Anand in 1998.

Rebel was a commercially available chess-playing program that was getting

stronger every year. The interesting thing about the encounter with Vishy was

to answer a simple question: Can a “regular” chess program beat

a top GM?

In contrast to Deep Blue’s ability to look at 200,000,000 nodes per

second (NPS), Rebel on a regular PC could look “only” at 200,000

NPS. In the previous year, Rebel had played the world number 12, Arthur Yusopov

in a total of 17 games (mostly blitz) and it had won 10½ – 6½

.

Against Anand, the format was a combination of 4 blitz games, 2 rapid games

and 2 games with classical time control. Anand played the blitz and rapid games

of Day 1, and Rebel trounced him 4.5-1.5. On the next two days, Anand played

the two slower games.

Anand drew the first slow game. In the last game he took Rebel into a 2R vs

R+2B endgame. With the help of advancing pawns, he won the game. Anand had

won the classical encounter, but the Rebel team also got to claim that they

beat the (then) world number two, 5 to 3.

2002: Rebel vs. Loek Van Wely

You can not play your own style against the computer,

that's about close to suicide

– GM Loek van Wely

Four years later, the Dutch GM van Wely (then rated 2714) took on the upgraded

version of the same program Rebel that Anand played for a 4-game match. The

encounter took place in February of 2002 with classical time controls (average

of 20 moves per hour per player). The interesting thing is that there were

no draws. The impressive thing is that Rebel won the first and the third games.

The admirable thing is that GM Van Wely had to come back and equalize in a

must win situation, which he did.

The Rebel team is proud of Game 3 in particular, which they have dubbed the

“perfect game.” The fourth game is a good example of how human

GMs can see farther ahead in multi-piece endgames. In the tail end of that

game, there are a couple of places where the computer loses the “thread”

of the idea and thus loses critical tempii. A 2700+ GM isn’t going to

let opportunities like that get away. Loek won the final game and the match

ended drawn.

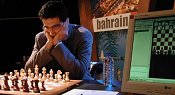

2002: Fritz vs Vladimir Kramnik, Brains in Baharain

“Believe me, to lose to a computer is twice as painful

as losing to a colleague.”

– GM Vladimir Kramnik, before his Brains in Bahrain match

This was the biggest Man vs. Machine event that did not feature Garry. Kramnik

was the world champion. Lots of human-interest aspects in this encounter.

The ChessBase folks seemed to have learned something from the way IBM handled

the match against Kasparov. True or not, Garry maintained that in 1997, IBM

had gone to great lengths to ensure that they defeated him at all costs. In

the Bahrain match, ChessBase wanted to steer clear of all the controversies

surrounding the Deep Blue match. (It is easy to see that this is a very wise

strategy. Unlike IBM’s tangential association with chess, ChessBase is

all about chess and they have to take the long-term view.) The Fritz team made

it clear that they wanted a fair contest. They were very open about the fact

that they were mainly after the publicity and the sales. Sure, the goal was

to beat Kramnik, but they didn’t want it to be through any non-chess

means – they wanted to beat the champ purely in chess.

In fact, to many it looked as if the team was bending over backwards and even

Kasparov voiced some objections. His web-based Kasparovchess.com posed ten

questions which the Fritz team then proceeded to

answer.

Kramnik’s second, GM Miguel Illescas was given an advanced copy of the

exact program ahead of time. The only thing that the Fritz team would be allowed

to tweak was the relative weightage to steer it to an opening of their choosing.

The general feeling was that Fritz stood no chance.

After the first three games, it did indeed look that way. Fritz had only managed

a 0.5 out of 3. At the half-way mark, Vladimir was leading 3-1, with no losses.

And then, it looked like Fritz woke up.

Here’s what Kramnik himself says about the next game, which he lost:

“In game

five Fritz played very well, better than any human. It seemed almost equal,

but it managed to keeping putting on this pressure all the time, it kept finding

these very precise moves, not giving me a chance to get away. I played that

game really well, and I shouldn't have blundered, but the position was not

so pleasant anyway. I must admit it simply played very well.”

Position in which Kramnik played the inspired Knight sac: 19. Nxf7!!?

Game six

was wonderfully fought. Fritz had black but it got a very good opening. The

position was complicated, as evidenced by the fact that Kraminik went into

a 42-minute think before playing his 19th move. He had decided to simply go

for it! Sac his Knight, get the black king out into the open and try to win.

As it turned out, he had overlooked the only defensive move for Fritz. 28…Bh4!!

Fritz, of course, had seen it all along. A great game, but Fritz got the point.

Against an opponent like Kramnik, who is notoriously difficult to defeat,

Fritz had snatched two games in a row to come back and equalize! Games seven

and eight were drawn, the match ended drawn.

| Bahrain 2002 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

Final |

| Vladimir Kramnik |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

4.0

|

| Deep Fritz |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

1

|

½ |

½ |

4.0

|

When Man vs. Machine games first started, there were anti-computer strategies

by GMs; then there were anti-GM settings by the programmers. The GM’s

got savvier, and the computer programs got better. Things had come a full-circle

as Kramnik stated in a post-match conference. “It was a normal fight,

I decided to play normal chess, not anti-computer chess.”

2003: Hiarcs vs Bareev

This match got dubbed the “other” Man vs. Machine. Four games,

four draws. But this is only on the surface. The interesting aspect is that

Bareev had not been shown any of the games of Hiarcs before this match. Also,

he only had one day’s rest after the grueling 13-round Wijk Aan Zee Corus

tournament. In the Corus tournament, he finished third with 7.5 points, ahead

of Kramnik, Shirov, Karpov and Ivanchuk among others. Bareev did well to draw

2.0-2.0 with Hiarcs.

2003: Garry Kasparov vs Deep Junior

“I’m calculating publicity factors, scientific

factors, psychological factors,

while the machine is just taking account of the chess factors.”

– Garry about Deep Junior

Earlier this year, Garry got another “big splash.” He took on

Deep Junior for six games. For many of us, the important feature of this confrontation

was the ESPN coverage. Chess being shown on ESPN – which true chess aficionado

hadn’t fantasized about that?

Garry won the first game, and in Game

3, Deep Junior equalized. Then the fourth game was drawn. In Game five,

Deep Junior made played 10. Bxh2!, a move which Garry himself later called

“an imaginative sacrifice of the type generally considered impossible

for a computer player” in a Wall Street Journal article. He hadn’t

been expecting the sacrifice and in fact his initial fear had been that he

was getting mated. However, he saw that the threat was a perpetual check, and

he managed to hold the game.

So, it all came down to Game 6. Lots and lots of spectators were tuned in

to ESPN, listening to the commentators Maurice Ashley and Yasser Seirawan.

After around 25 moves each, the game was turning exciting. The commentators

were warming to the position, the audience was growing expectant.

Then, after Deep Junior played 28. f4 the team offered a draw. Surprising

many, Garry accepted. Many fans didn’t like the fact that Garry agreed

to a draw. GM Ashley, who was commenting, mentions about how his mother-in-law

watched this particular game on TV for 3 hours even though she had never ever

played chess, and was very disappointed with the draw. Maurice Ashley was worked

up enough about the draw to write an article about it – The End of the

Draw Offer? However, we should remember that it is easy for us fans to be bloodthirsty

– we don’t have any skin in the game, whereas Garry does.

| New York 2003 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

Final |

| Garry Kasparov |

1 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

3.0 |

| Deep Junior |

0 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

3.0 |

2003: Garry Kasparov vs X3D Fritz

It is a risky endeavor to try to predict the outcome of any of these matches.

However, a strong case can be made for those who would like to believe that

this time, Garry is just going for it. As we have just seen, Garry has more

than enough experience in playing matches against computers. Also, Garry’s

championship match with Ponomariov never materialized. He has sat out of the

rapid championship in Cap’D Agde. So, it is fair to assume that Garry

is hungry for a victory or two.

Imagine the joy in demolishing the arguments of those who’ve maintained

that it is only a matter of time before humans lose to computers. Imagine ending

up with a score of +2. Imagine laying the foundation for a future encounter

with another super-strong chess program – another big splash. Well, you

can be sure that Garry is imagining all that and more.

Links:

Ram Prasad is a Chicago-based software engineer, originally

from India. He is a part-time writer and a full time chess junkie who is fascinated

by super GMs and mega tournaments.

At

that time, Feng-Hsuing Hsu, a grad student originally from Taiwan, was pursuing

his Ph.D. in Carnegie Mellon University. Hsu’s topic of choice for his

thesis was to build a very advanced chess-playing computer. His program ran

on linked processors in parallel, and had been named Deep Thought. (Incidentally,

this started the trend of using the prefix “deep” to denote parallel

processors.) Deep Thought and its evaluation algorithms were the subject discussed

in many ACM gatherings. In the computer chess world, Deep Thought was a giant.

At

that time, Feng-Hsuing Hsu, a grad student originally from Taiwan, was pursuing

his Ph.D. in Carnegie Mellon University. Hsu’s topic of choice for his

thesis was to build a very advanced chess-playing computer. His program ran

on linked processors in parallel, and had been named Deep Thought. (Incidentally,

this started the trend of using the prefix “deep” to denote parallel

processors.) Deep Thought and its evaluation algorithms were the subject discussed

in many ACM gatherings. In the computer chess world, Deep Thought was a giant. In

the early to mid-nineties, chess-playing software were evolving into commercially-sold

entities. Fritz, Rebel and Genius started to take shape. Inevitably, this led

to a revived interest in Man vs. Machine matches.

In

the early to mid-nineties, chess-playing software were evolving into commercially-sold

entities. Fritz, Rebel and Genius started to take shape. Inevitably, this led

to a revived interest in Man vs. Machine matches.

While

everyone remembers Kasparov vs. Deep Blue, there was another big man vs. machine

event that went unnoticed by comparison. But the true computer-chess fans still

remember AEGON 1996 – organized in the Hague – with fifty strong

chess programs being paired with 50 strong GMs and IMs.

While

everyone remembers Kasparov vs. Deep Blue, there was another big man vs. machine

event that went unnoticed by comparison. But the true computer-chess fans still

remember AEGON 1996 – organized in the Hague – with fifty strong

chess programs being paired with 50 strong GMs and IMs.  In the natural progression of man vs machine matches, we next saw Game Theory

in its truest sense. Even as GM’s were getting savvier in their play

against computers, (steering the game towards positional chess as opposed to

tactical, to put it simplistically) the computer programmers were doing the

exact opposite. This led to the so-called “anti-grandmaster” chess,

which culminated in the program Rebel being programmed and readied

for months specifically to face GM Anand in 1998.

In the natural progression of man vs machine matches, we next saw Game Theory

in its truest sense. Even as GM’s were getting savvier in their play

against computers, (steering the game towards positional chess as opposed to

tactical, to put it simplistically) the computer programmers were doing the

exact opposite. This led to the so-called “anti-grandmaster” chess,

which culminated in the program Rebel being programmed and readied

for months specifically to face GM Anand in 1998.