Linares, Linares! – All over again

A book review by Nadja Wittmann

Once a year some of the world's sharpest minds gather in the Andalusian town of Linares. In the splendid isolation of Don Luis Rentero's Hotel Aníbal, the leading grandmasters of chess decide, as Garry Kasparov puts it 'who is who for the coming year'. The Linarese proudly speak of the Wimbledon of Chess.

This time ChessBase asked me to go to Linares, to do a series of photo reports during the tournament. It was my first trip to the famed Supertorneo "Cuidad de Linares", and I was glad to be travelling with the veteran ChessBase roving reporter Frederic Friedel, who did the live game coverage on the Playchess.com server.

| |

Published by New In Chess, 2001, English, paperback, 128 pages,

ISBN: 90.56911.077.9

Price: € 15.84

|

Some weeks before we left Frederic handed me a lovely book entitled "Linares! Linares!", written by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam, the editor of New in Chess magazine. It was a very important book, containing such a wealth of information on the history of the tournament, the players and the city, that I arrived in Linares fully equipped with all the information needed to feel immediately at home in the chess environment. It was an uplifting feeling to meet people and see places for the first time and already know a lot about them. Every time Frederic introduced me to anyone it was like meeting an old friend.

Linares! Linares! is the engrossing evocation of the games, intrigues and conflicts that have made the supertorneo a unique tradition. We meet the players and the aficionados. The book poses many enigmatic questions. Why does Vassily Ivanchuk have trouble praying when he is thinking of God? Was Gata Kamsky's orange juice really poisoned? Why did Judit Polgar exclaim 'How could you do this to me?', when she confronted Kasparov in the lobby of the Anibal? Was it a coincidence that general Juan Perea's son got married in Mexico on the day when Manolete was killed in the Linares bullring? And perhaps the most intriguing question the author tries to answer: why does time come to a standstill in this provincial Spanish town when the chess players arrive?

Linares! Linares! is the engrossing evocation of the games, intrigues and conflicts that have made the supertorneo a unique tradition. We meet the players and the aficionados. The book poses many enigmatic questions. Why does Vassily Ivanchuk have trouble praying when he is thinking of God? Was Gata Kamsky's orange juice really poisoned? Why did Judit Polgar exclaim 'How could you do this to me?', when she confronted Kasparov in the lobby of the Anibal? Was it a coincidence that general Juan Perea's son got married in Mexico on the day when Manolete was killed in the Linares bullring? And perhaps the most intriguing question the author tries to answer: why does time come to a standstill in this provincial Spanish town when the chess players arrive?

Well, I found out! Naturally by reading Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam's marvellous book, and then by wandering around Linares, visiting all the places together with the author himself.

So, let's go, Dirk Jan! Show us what Linares, Linares! is like!

In his book Dirk Jan writes:

Automatically, I walk in the direction of the town hall. I am taking the chess player's constitutional, an established, predictable route leading on from the Plaza del Ayuntamiento through the shopping mall and then upward through two busy streets, where motorized traffic is allowed, finally to join the paseo, the favourite Sunday promenade for all of Linares.

At the end of the paseo is the statue of Andres Segovia. A huge bronze statue of a gruff, bespectacled man in a wide cloak wearing remarkably large, black shoes. There, at the statue of this famous son of Linares, is the turning point.

The greatest classical guitarists of all time: Andrés Segovia (1893–1987)

The Linarese are proud of their paseo, built originally at the end of the nineteenth century. In the late twenties, the paseo underwent its most drastic change.

Every other ten metres, stone benches were put under the palm trees, decorated from top to bottom with brightly-coloured Andalusian tiles, baked for the purpose in Seville. On the back of these benches Linarese shopkeepers could – and still can – advertise their trade.

The Secret Miracle

Linares is perhaps so often said to be ugly because there is a conspicuous lack of cheerful Andalusian architecture. Houses and buildings almost everywhere radiate the indifference with which they have been constructed.

At an angle off the paseo is one of the few exceptions: the arena, which demonstrates, with its brightly whitewashed walls and the wide yellow ochre bands marking gates, windows and eaves, that it doesn't have to be that way. Located in all its splendour in the midst of a number of drab apartment buildings, it seems to accentuate how deeply bull fighting is still entrenched in Spanish daily life. Jam-packed corridas are still being held here.

Approaching the arena, Dirk Jan suddenly gets a day-dreaming expression on his face and tells us the story of his very personal experience with The secret miracle and how he had recognized – and even proved – that in Linares time stands still once a year. And this is not the only "secret miracle" that can happen to you in Linares!

On the Corredera de San Marcos, which is wider, new alluring fragments reach my ears. From over the high roofs of the bank buildings, they swirl down through the noise of the street. There is no longer any doubt in my mind that the music is coming from the bullring. Especially not when I turn the corner at the traffic lights at the high end of the street and I see the white arena with its ornamental ochre borders in front of me, surrounded by palm trees. The music is loud now, inescapable and at times downright shrill.

Crossing the small park in front of the arena, I quickly walk on up until I reach one of the imposing gates, painted in ox-blood red. Huge white letters indicate that this is the Entrada Palcos, with, underneath it, the important addition: Sombra. This is the entrance for the better seats, which are not in the glaring sun towards the end of the afternoon but comfortably protected in the shade.

One of the two doors in the gate is open. Not knowing whether an outsider is welcome here, I look in hesitantly. There are two boys in the archway, about sixteen years old and both dressed in blue jeans and bright polo shirts. One of them turns round. He sees that I am interested and with emphasis beckons me to enter. It is clear from his encouraging look that he knows that I am not from around here. Reassured, I make my way into the cool entrance until I have a good view of the arena, which extends white and bare from the fence guarding the front seats.

There, with their backs towards me, are the trumpet players who lured me into coming here. Across the stretch of white sand, another group – also some ten men strong – are beating their drums in a syncopated rhythm. They are practising with concentrated, silent faces, in their everyday clothes. The merging music resounds in the archway and grabs me in the midriff. It is as if a thin layer has formed all over my body, of which even the tiniest part contributes to my senses. The brass is wailing, demanding a deep sense of time. The drum beat seems to want to drive the music on, but is marking even more the here and now of the moment.

Turning around myself, I try to comprehend what it is that the music has made clear to me. Why I have the feeling that I understand now what makes me like to come to Linares so much. And then, all of a sudden, the realization is there in words. Rentero used to say: "Linares es Linares," whenever he wanted to explain what was so unique about his tournament. I now hear my own explanation behind his words. Linares is Linares, because this is where every year time comes to a stop. Every year there is a new tournament and every year it is also the same. While commerce is rushing chess, demanding ever faster games, the players here are given the opportunity to fight their battles at a classical pace, undisturbed by the obtrusive outside world. Linares hasn't given in to the illusions of the present time. Not yet. No, here, time has been sidetracked. Here, time stands still once a year."

Manolete

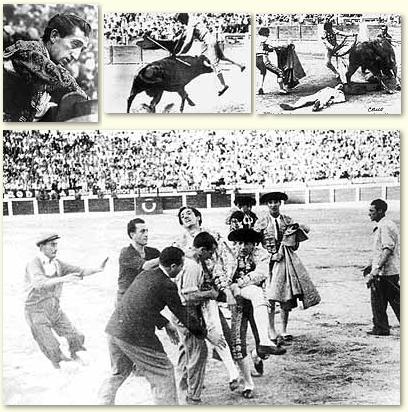

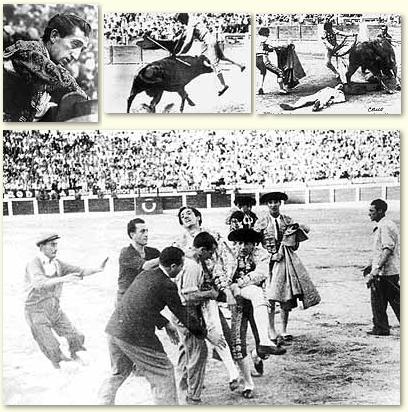

The first time I saw Manolete, I had hardly any idea who he was. Cast in bronze, he stood in front of me all of a sudden. With his upper legs rising from a white stone pedestal in an untidy public garden behind the bullring, he was looking down at me, sympathetical but self-assured. The trampled patch of grass in front of the statue might lead one to surmise the regular presence of hordes of admirers. But ice-cream wraps and empty tins carelessly strewn across the ground were indicative of the actual lack of interest to which he had fallen prey in this out-of-the-way corner of Linares. Manolete's right arm was hanging loosely along his side, the left hand leaning pertly on the thigh. It was clear from his tightly fitting costume that he must have been a bullfighter. In carved letters, with some hurriedly sprayed graffiti underneath, Linares honoured the memory of Manuel Rodriguez Sanchez, called Manolete. There were two dates on the plinth. August 28th, 1947 and August 28th, 1972. Amazing, I thought in my ignorance, he has died here in the arena on his twenty-fifth birthday.

I was wrong, of course. The small monument is in memory of the twenty-fifth anniversary of the death of the torero, who was a much greater celebrity than I realized at the time. The day when Manolete was carried out of the Linares arena, fatally wounded, was a day stamped in the memory of countless Spaniards. August 28th, 1947, was a mark in time. A memory pivot in history. You indicated that something had happened before or after Manolete's death. 'The year when Manolete died' became a fixed expression, which evoked indelible images and harrowing details. From Manolete groaning with pain on the shoulders of his comrades to Manolete lifeless in Linares hospital. You can ask generations where they were when the news of Manolete's death plunged the country into mourning. Few will have to think long how and where they heard the sad news.

Las manoletinas – a special move used by Manolete

Last year, during the feria in Seville - one of the many holidays in Spain when corridas add to the festivities – I discovered a stand full of more or less voluminous works on the history of bullfighting in a local bookshop... The most fascinating work on the book stand was Vida y Tragedia de Manolete, The Life and Tragedy of Manolete, more than six hundred pages of pictures and testimonies, which leave nothing unsaid and nobody unmentioned. Countless pictures take the reader back to the hours before and after the fatal fight.

The core of the book is a unique photo-report of the actual fight itself. It opens with a series of pictures illustrating the atmosphere. Spectators around the arena, with small notice boards everywhere saying: 'No more tickets available.' Impressions of the packed stands. Then there is Manolete entering the arena. The caption aims at poetry: 'The last smile. A salute to the public in recognition of their ovation.' The first skirmishes, and then, on page 467, the descabello, the fatal thrust, which will also be his own. As Manolete bends over the bull with his sword in his right hand to plunge it in between the shoulder blades, the bull Islero sinks his right horn into his attacker's thigh.While colleagues and onrushing friends carry Manolete out of the arena posthaste, Islero is dragged out with ropes. Out of view of the crowd and the cameras, the men of the Mesino butcher's shop, which had a contract with the arena, took care of the dead bull. Islero's head was not stuffed like a hunting trophy, as was often the case with corrida bulls. The only thing to remain of the bull today are its horns, which were snapped up and proudly saved by the owner of the Taberna Lagartijo in Linares.

Mauricio

Mauricio and Nieves Perea were married on the day when Manolete lost his life in the arena of Linares. In accordance with the traditional morning ritual at the Hotel Anibal, we sit chatting in the lobby, surrounded by newspapers and with guests coming and going. The subject of Manolete stirs up a hoard of memories with Mauricio. Enthusiastically, he pushes off.

"Manolete was out of the ordinary. It was not for nothing that people used to call him El Monstruo, the Monster, the greatest of the great. A year before he died in Linares, I saw him in Mexico. He appeared twice. His first performance earned him two ears and a tail. Manolete did something that no one else ever did. It often happens that a bull approaches a torero with its head somewhat to the side and the torero then automatically makes a small step backward to give the bull a wide berth. Manolete never used to do that. He was completely stoical; standing still, he tried to manipulate the bull with his cloth in such a way that it would avoid him.

That is how I saw Manolete get hurt in his second fight, motionlessly directing the bull. The bull didn't turn aside and Manolete was seriousy injured in his left thigh. I even remember the name of the reporter who interviewed him in hospital after the incident. His name was Pepe Alameda and he asked Manolete why he hadn't stepped back. His answer was: Because if I did I wouldn't be Manolete.

Yes, Manolete. The sad thing was that he died because of ignorance. Or a lack of knowledge, or whatever you want to call it. He'd had a blood transfusion, but there was also a famous doctor from Madrid who got into his car the moment he heard what had happened to drive to Linares with the latest thing: gamma-globuline. No one here had ever heard of it, naturally. Or they didn't exactly know what to do with it. It appears that Manolete had some allergy or other, because he died right after he was given this injection. Which was tragical, because he was immensely popular. I knew many Mexican families who brought financial ruin upon themselves, because they'd spend all they had to get tickets for one of Manolete's fights."

"I can't believe my ears, Mauricio. You loathe bullfighters, don't you?" He squeezes his lips together, as though he realizes himself that there is an amusing side to his outpouring. "But I was different then. My father also was a great aficionado. Just as he loved everything Andalusian. It was the same with me. With all sorts of music too. It filled me with melancholy and nostalgia. Years later, after I had returned from America to Spain, I couldn't possibly understand what I'd gotten so nostalgic about when I heard these drivellers sing. Those feelings had disappeared entirely."

Who else but Maurcio Perea could be more appropiate to put into words what Linares is? This is a dream that he told Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam some years ago and his words seem to be as topical as ever…

"Two nights ago I had a dream. I wrote it down the next morning in my study. I dreamt it was a windless day. A lovely blue sea stretched out without so much as a ripple under a radiant sky. The sun was delightfully warm and caressed everyone who was willing to enjoy it. The pavement cafés were full of people sitting peacefully under colourful parasols. Smiling, talking women kept an eye on children playing with boundless energy in the sand. The men were playing chess, engrossed in their game. All of a sudden, without any previous warning, a tidal wave rose up out of the sea, shattering the idyllic scene at one grim stroke. The parasols toppled, the tables were pushed aside and sucked away, and the chess board squares melted together into a sinister, blue-green plane. Heads with terrified, wide-open eyes were trying to remain above the water. "But not for long. As suddenly as it had arisen, the enormous wave withdrew and peace was restored to the beach, just like in a film running in reverse. The women were talking again, the children, unworried and self-absorbed, returned to their play, and the men were playing chess again. And yet, it was not as it had been before. Something essential had changed. It was clear to everyone now that this serene calm could be disturbed at any moment by a violent wave." Mauricio looked at his hands for a moment and said: "Underneath it I wrote: This is Linares."

Part two: Linares, Linares... I-van-chuk!

Links

Picture reports from Linares by Nadja Woisin:

Published by New In Chess, 2001, English, paperback, 128 pages,

ISBN: 90.56911.077.9. Price: € 15.84

Linares! Linares! is the engrossing evocation of the games, intrigues and conflicts that have made the supertorneo a unique tradition. We meet the players and the aficionados. The book poses many enigmatic questions. Why does Vassily Ivanchuk have trouble praying when he is thinking of God? Was Gata Kamsky's orange juice really poisoned? Why did Judit Polgar exclaim 'How could you do this to me?', when she confronted Kasparov in the lobby of the Anibal? Was it a coincidence that general Juan Perea's son got married in Mexico on the day when Manolete was killed in the Linares bullring? And perhaps the most intriguing question the author tries to answer: why does time come to a standstill in this provincial Spanish town when the chess players arrive?

Linares! Linares! is the engrossing evocation of the games, intrigues and conflicts that have made the supertorneo a unique tradition. We meet the players and the aficionados. The book poses many enigmatic questions. Why does Vassily Ivanchuk have trouble praying when he is thinking of God? Was Gata Kamsky's orange juice really poisoned? Why did Judit Polgar exclaim 'How could you do this to me?', when she confronted Kasparov in the lobby of the Anibal? Was it a coincidence that general Juan Perea's son got married in Mexico on the day when Manolete was killed in the Linares bullring? And perhaps the most intriguing question the author tries to answer: why does time come to a standstill in this provincial Spanish town when the chess players arrive?