Ludek Pachman, 1924 – 2003

By Frederic Friedel

|

| Ludek Pachman in 1996 |

The Czech grandmaster Ludek Pachman died on March 6, 2003, in the city of Passau,

Germany. He was 78 years old.

Pachman was born on May 11, 1924, in Czechoslovakia. Beween 1945 and 1968 he

played very successfully in many international chess tournaments, including

Interzonals. In fact in the Sicilian

Vespers story we told for Bobby Fischer's 60th birthday Ludek Pachman was

one of the players Fischer had to stay ahead of in the final round of the 1958

Portoroz Interzonal to qualify for the Candidates' Tournament.

In an article in the German language chess magazine Karl

Pachman describes his first encounter with Fischer: "I met him for the

first time in May 1959 in Santiago de Chile [apparently Pachman had not "met"

Fischer properly the year before in Portoroz]. On the day before the tournament

he asked me to translate for him. He had arrived in Chile accompanied by his

mother, and the organiser wanted to know if the two needed separate rooms. Bobby

replied: 'You haven't understood, I want you to put up my mother in a room that

is at least ten miles away!' Then he wanted to know about the prize money. The

organiser asked if he hadn't read the letter of invitation? "I never read

letters," said Bobby. The prize money that was named was too low and he

threatened to leave. I told him his behavious was not correct, but he simply

said ‘I have to get more.’

We stayed in the same hotel and talked every day, often preparing together

for our games. That was unusual, since Bobby refused to analyse with the other

players. He was suspicious of them all, fearing they would steal his ideas.

But for some reason he considered me an exception. We had a kind of father-son

relationship. I understood him and wished him a great future, hoping that he

would mature as a human being in the process. But he remained exactly the same.

He was completely apolitical. He hated the Russians, but not for political reasons.

The last time I met him was at the chess Olympiad 1968 in Lugano. This was just

a few weeks after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslavia. I was trying to get FIDE

to expel the Soviet Union from the tournament and from the world chess organisation.

After a press conference Fischer came to me and thanked me for attacking the

Soviets. 'Keep it up, attack the Russians,' he said." Here's the game

from the Santiago tournament between the two:

Pachman,L - Fischer,R [D07]

Santiago de Chile (6), 1959

1.Nf3 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.d4 d5 4.e3 Nc6 5.Nc3 Bb4 6.Bd2 0-0 7.a3 Bxc3 8.Bxc3

Ne4 9.Qc2 a5 10.b3 b6 11.Bb2 Ba6 12.Bd3 f5 13.Rc1 Rc8 14.0-0 Rf6 15.Rfd1 Rh6

16.Bf1 g5 17.cxd5 g4 18.Bxa6 gxf3 19.gxf3 Qg5+ 20.Kf1 Rxh2 21.fxe4 Rf8 22.e5

f4 23.e4 f3 24.Ke1.

Instead of protecting his knight (24...exd5 25.exd5 Ne7) with good winning

chances the impestuous Fischer went after his opponent's king. This was a mistake

that Pachman severly punished. 24...Qg1+? 25.Kd2 Qxf2+ 26.Kc3 Qg3 27.Qd3

exd5 28.Rg1 Rg2 29.Rxg2 Qxg2 30.Qf1 dxe4 31.Qxg2+ fxg2 32.Rg1 Rf2 33.Bc4+ Kf8

34.Bd5 Rf3+ 35.Kc4 b5+ 36.Kc5 Ne7 37.Rxg2 Nxd5 38.Kxd5 Rxb3 39.Kxe4 b4 40.axb4

axb4 1-0.

In the year of the invasion of his country Pachman was arrested in Prague,

in the middle of the night, and was taken to a torture cellar where he was almost

killed. On Christmas Eve 1969 the doctors called his wife to inform her that

he would probably not survive the night. He did, and in the early Seventies

he emmigrated to West Germany, where he soon became know as an political activist,

with strong anti-communist views. His eloquence brought him regular appearances

on political talk shows.

|

Read more details in The

Prague Spring, an article that tells the tale about two Czech champions

– Ludek Pachman and Lubosh Kavalek. It talks about Pachman's book

"Checkmate in Prague: memoirs of Ludek Pachman"

(which Amazon

is offering for $108.27).

In the first paragraph of Checkmate in Prague Pachman

writes: "At an international tournament a journalist once asked

me how I came to play chess. I told him that my aunt had taught me, but

that hers was a somewhat different game – she put bishops in the

place of knights and vice versa. The Estonian grandmaster Paul Keres,

who heard the conversation, remarked with his typical dry humour: 'Of

course, one needs to bear that in mind when reading your books on chess.'"

During the 1943 Prague tournament, Pachman's first serious event at the

age of 18. In Checkmate in Prague he writes:

"After [my win over Foltys], the great Alekhine

invited me to his room. He got me to demonstrate my game, made a few comments,

praised me, and then showed me his game, explaining several hidden combinations

and also accepting praise. Mrs. Alekhine was there with her two cats.

I had to hold one for a bit and the wretch scratched me, but it was a

marvellous evening, something in the nature of a high-point in my life

so far.

Alekhine took to inviting me in every day. We always

analysed something and I soon discovered that it was no good disagreeing

with him because it made him angry. So I just listened reverently to what

he said. He invited me for coffee, too. In the Luxor cafe, it seemed,

one could get real coffee under the counter – an expensive luxury

for which I had to foot the bill. Alekhine, I discovered, made a point

of not paying. Usually there was someone with him, otherwise he simply

walked out of the restaurant. The waiters knew him, so they sent the bill

to the tournament director. I learnt also from a very annoyed Mr. Kende

that by threatening to walk out of the tournament, Alekhine had extracted

a 5,000 crown addition to his original 40,000 crown fee. Luckily I was

saved by an unexpected patron. He was Mr. Stork, a trader and landowner,

who presented me with an enormous salami in recognition of my achievement,

plus an invitation to lunch every day at his house. The meals were better

than any I have eaten even in peacetime, and by doing without supper I

was able to pay for Alekhine's coffee."

|

Pachman and the computer

I first met Ludek Pachman in 1979. As a rookie science journalist I was making

a documentary film on computer chess. It was centered around a match between

IM David Levy and the program Chess 4.7 running on a CDC Cyber 176 mainframe

computer. As part of the event we staged a simultaneous exhibition for local

players against the computer, which was located in Minneapolis, USA. We also

invited Ludek Pachman to talk to the audience and play an informal game against

Chess 4.7.

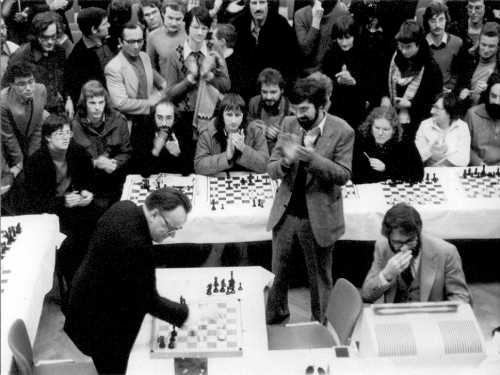

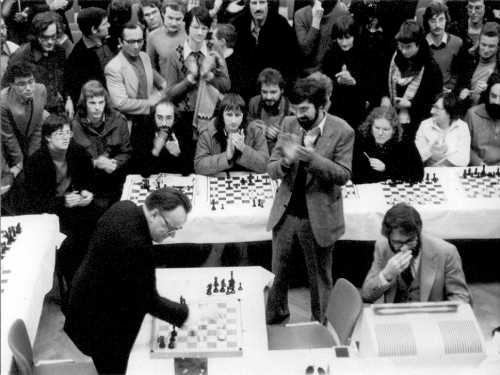

In the above historical picture, taken on February 4, 1979, we see Prof. Frieder

Schwenkel of the University Hamburg explaining the computer to GM Pachman.

The blitz game, with the author of this article executing the computer moves.

Pachman wins the game against Chess 4.7. The computer operator is the famous

Dave Cahlander of Control Data.

After the computer chess film had been aired, and another produced and broadcast,

the subject became a favourite topic on German TV talkshows. These were the

years when the first commercial chess computers appeared. I was on a number

of shows together with Pachman, who was very professional about it. After the

first one had been a fairly boring discussion on how computers play chess he

said to me: "Listen, we need to be more adversarial." And from then

on he always made it a point of interrupting me in the middle of a sentence,

putting his hand on my arm and saying "But dear Mr Friedel, that is patently

wrong...". We had some nasty arguments – and the audience loved it.

It wasn't difficult to pick a fight with Ludek. In computer chess he would,

if a demo board was available, show a series of beautiful positions which a

computer could "never understand or solve". They were always positions

in which you had to find an "exception", something extremely creative

or imaginative. One of his favourites was a chess problem with multiple underpromotions

to bishops. I would become (genuinely) agitated and protest that these were

exactly the kind of thing computers excel at; it was long-range planning and

strategic play in which they were hopelessly inferior to grandmasters. But even

when I showed him that some of the board computers had learnt underpromotion

and were solving his positions, he stuck to his arguments. They were much too

good to be abandoned just because they were no longer completely accurate. As

I said: the audience loved it.

The last time I saw Ludek was on May 11th last year (the thumbnail picture

on our front page was taken there). He was an honoured guest at the 125th Jubilee

celebration of the German Chess Federation. He was frail but cheerful. We discussed

doing a video interview, but there were too many other things going on. Now

it will never get done. How sad.

Links

Dossier

Active years of Ludek Pachman (total number of games in the database: 1629)

Career highlights

| Zlin 1943 |

|

9.5/13

|

+6

|

Rank 3

|

| Prague 1945 |

|

6.5/10

|

+3

|

Rank 3

|

| Arbon 1946 |

|

5/7

|

+3

|

Rank 3

|

| Hilversum zt 1947 |

|

9.5/13

|

+6

|

Rank 2

|

| Warsaw 1947 |

|

6/9

|

+3

|

Rank 3

|

| Southsea 1949 |

|

8.5/10

|

+7

|

| Trencianske Teplice 1949 |

|

13.5/19

|

+8

|

Rank 3

|

| Venice 1950 |

|

9.5/15

|

+4

|

Rank 4

|

| Marianske Lazne zt 1951 |

|

13/16

|

+10

|

Rank 1

|

| CSR-ch Prague 1953 |

|

10.5/15

|

+6

|

Rank 2

|

| CSR-ch Prague 1954 |

|

12.5/17

|

+8

|

Rank 2

|

| CSR-ch m Prague 1954 |

|

3.5/6

|

+1

|

Rank 1

|

| Prague zt 1954 |

|

15/19

|

+11

|

Rank 1

|

| Hastings 5455 1954 |

|

5.5/9

|

+2

|

Rank 4

|

| Mar del Plata 1955 |

|

9.5/15

|

+4

|

Rank 4

|

| Dresden 1956 |

|

9/15

|

+3

|

Rank 4

|

| Marianske Lazne/Praha 1956 |

|

12/19

|

+5

|

Rank 4

|

| Prague m 1956 |

|

2.5/6

|

-1

|

Rank 2

|

| Dublin zt 1957 |

|

14.5/17

|

+12

|

Rank 1

|

| Gotha 1957 |

|

10.5/15

|

+6

|

Rank 2

|

| CSR-ch Bratislava 1959 |

|

12.5/17

|

+8

|

Rank 1

|

| Lima 1959 |

|

10.5/13

|

+8

|

Rank 2

|

| Santiago 1959 |

|

9/12

|

+6

|

Rank 2

|

| Mar del Plata 1959 |

|

10.5/14

|

+7

|

Rank 2

|

| Sarajevo 1960 |

|

7.5/11

|

+4

|

Rank 2

|

| CSR-ch Kosice 1961 |

|

14/19

|

+9

|

Rank 1

|

| Sarajevo 1961 |

|

7.5/11

|

+4

|

Rank 2

|

| Graz 1st 1961 |

|

9/11

|

+7

|

Rank 1

|

| CSR-ch Prague 1963 |

|

14.5/19

|

+10

|

Rank 1

|

| Capablanca mem 1963 |

|

16/21

|

+11

|

Rank 4

|

| Kecskemet zt 1964 |

|

9.5/15

|

+4

|

Rank 3

|

| Sarajevo 1966 |

|

10/15

|

+5

|

Rank 4

|

| CSR-ch Int 1st 1966 |

|

11/17

|

+5

|

Rank 3

|

| Solingen 1968 |

|

9/15

|

+3

|

Rank 3

|

| Netanya-A 1973 |

|

9.5/15

|

+4

|

Rank 3

|

| Eckernfoerde tt 1974 |

|

4/5

|

+3

|

Rank 3

|

| FRG-ch int Mannheim 1975 |

|

10.5/15

|

+6

|

Rank 2

|

| Barcelona zt 1975 |

|

4.5/7

|

+2

|

Rank 3

|

| Reggio Emilia 7576 1975 |

|

6/9

|

+3

|

Rank 1

|

| FRG-ch Bad Neuenahr 1978 |

|

8.5/11

|

+6

|

Rank 1

|

| Bayern-ch Pang 1983 |

|

8.5/12

|

+5

|

Rank 1

|

| Sindelfingen 1984 |

|

8/13

|

+3

|

Rank 4

|

Addendum

Shortly

after we had uploaded this article on Ludek Pachman we received an email from

Ljubomir Kavalek (left), a compatriot and fellow grandmaster, who writes the

chess column for the Washington

Post. Lubos will be publishing his Pachman eulogy in the Monday issue of

the newspaper, but he kindly sent us his rough notes on Ludek Pachman, which

we share with you here.

Shortly

after we had uploaded this article on Ludek Pachman we received an email from

Ljubomir Kavalek (left), a compatriot and fellow grandmaster, who writes the

chess column for the Washington

Post. Lubos will be publishing his Pachman eulogy in the Monday issue of

the newspaper, but he kindly sent us his rough notes on Ludek Pachman, which

we share with you here.

Ludek Pachman (1924-2003)

The Czech grandmaster, prolific writer, coach, teacher, composer, passed away

on March 6, 2003 in Passau, Germany.

Born on May 11, 1924 in a small Czech town Bela pod Bezdezem. Pachman had to

walk for his first title to a nearby village Cista (population 900) that had

a chess club with 110 members. Pachman became their champion in 1940.

Pachman's first break came in 1943, when he was invited to an international

tournament in Prague at the last moment. Alekhine dominated the event, Keres

was second. Pachman finished in the middle (9th place among 19 participants).

Alekhine paid him a compliment in an article in the "Frankfurter Zeitung"

and from the fifth round on invited him every evening to analyze games and opening

variations. "I don't have to tell you how a beginner from a village chess

club felt at that time," Pachman wrote. It might have triggered Pachman's

interest in the openings and in 1950s he became world's leading opening expert,

publishing his four-volume "Theory of Modern Chess."

In December 1954, shortly after I learned how the chess pieces move, I called

Pachman, the leading Czechoslovak grandmaster at that time, and challenged him

to a game of chess, explaining him my plan to defeat him. Of course, Pachman

laughed at the proposition of a 11-year old boy, but did not forget about me.

Four years later, after I became one of Prague's strongest players, he invited

me to analytical sessions with members of the Czechoslovakian Student olympiad

team. This was unusual since they were at least five years older, but I was

very happy to get the first glance how a professional player works. Only later

I learned that Pachman had a similar experience in his youth with Alekhine.

Pachman won the Czechoslovakian championship seven times (the first time in

1946, the last in 1966). He became German champion in 1978. He played in six

Interzonal tournaments (first time in Saltsjobaden 1948, last time in Manila

1986). and reprezented Czechoslovakia on chess olympiad (1952-1966). In 1962

he coached in Cuba and in 1967 in Puerto Rico.

By his own count he won 15 international tournaments, but considers sharing

second place in Havanna 1963 with M. Tal and E. Geller, behind V. Korchnoi,

his best tournament success.

His most productive year seems to be 1959. After winning the Czechoslovakian

championship he went on South American tour, winning tournaments in Mar del

Plata (togheter with M. Najdorf), Santiago de Chile (with Ivkov) and Lima (again

with Ivkov). On this tour he defeated 16-year-old Bobby Fischer twice. In the

same year he finished "Modern Chess Strategy," a fine book he thought

to be his best. Pachman published some 80 books in five languages.

Politcs always played a major role in Pachman's life and interrupted his chess

career several times. He was a passionate speaker and writer whatever cause

he defended, pro-communist early in his life or against communism after 1968.

It was hard to predict whether Pachman considered you to be his friend or his

enemy. He loved to argue and often changed his mind about people.

At the 1964 chess olympiad in Tel-Aviv I played the Steinitz variation of the

King's gambit against the Soviet champion Leonid Stein in the last round. Pachman

became furious watching my king's march on the board full of pieces and told

me: "You have insulted the Soviet school of chess and you will see the

consequences after we return to Prague." I didn't know at that time that

Pachman pre-arranged draws on the first three boards with the Soviets, guaranteeing

them the gold medals. My gambit play threatened to blow the deal.

In 1967 Pachman began to change his beliefs, fully confronting the communist

regime after the Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia in August 1968. In October

we went together to the Olympiad in Lugano, where the Soviets threatened to

expel South Africa from FIDE. We argued that the Soviet Union and other Warsaw

Pact countries that invaded Czechoslovakia should be expelled. The Soviets took

their proposal back.

In December 1968 Pachman won a tournament in Athens, but after his return to

Prague his life took another turn. He was soon imprisoned and even tried to

commit suicide. I had a long correspondence with prof. Max Euwe, who tried to

help Pachman at that time.

In the night of November 28, 1972, Pachman was allowed to leave Czechoslovakia

and arrived in Munich with his wife and their cat. Grasping the idea of freedom

the cat soon disappeared into hotel hallways and it took us some time to find

him.

I never understood why Pachman would try to steer conflict with people who

tried to help him, whether it was prof. Euwe or Egon Evertz, who arranged Pachman's

move from Prague to Solingen and helped him to acquire German citizenship.

After his arrival in Germany Pachman was often boycotted by East-bloc countries,

but he prevailed and they ended their harassment after Pachman qualified for

the 1986 Interzonal in Manila.

After the Velvet revolution in November 1989 Pachman acquired back the Czechoslovakian

citizenship, but in 1998, after being disillusioned with the Czech government,

he gave it back and settled in Passau.

Shortly

after we had uploaded this article on Ludek Pachman we received an email from

Ljubomir Kavalek (left), a compatriot and fellow grandmaster, who writes the

chess column for the

Shortly

after we had uploaded this article on Ludek Pachman we received an email from

Ljubomir Kavalek (left), a compatriot and fellow grandmaster, who writes the

chess column for the