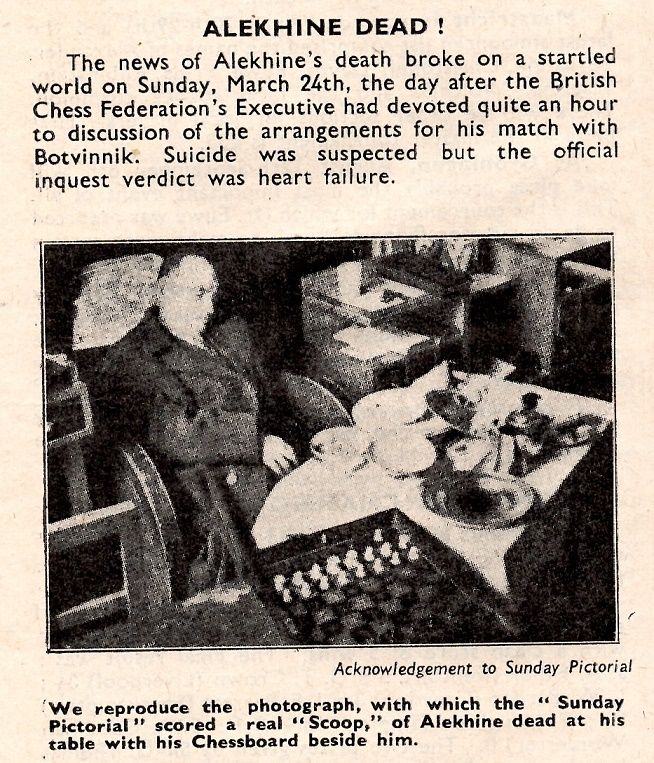

At the beginning of 1946. Mikhail Botvinnik (USSR), probably the best chess player of that time, got approval from the Soviet government to play a match against Alexander Alekhine in London.

At the beginning of 1946. Mikhail Botvinnik (USSR), probably the best chess player of that time, got approval from the Soviet government to play a match against Alexander Alekhine in London.

Everything looked set, and FIDE didn't receive any objections; however, two days after receiving the challenge, Alexander Alekhine was found dead in his hotel room in Estoril, Portugal. The title for the strongest chess player on the planet became vacant.

During its first post-war congress (1946 in Winterthur, Switzerland), FIDE was represented by seven countries – importantly without the USSR Chess Federation. Alexander Rueb was elected President for the next four years. At this congress, the rules for the future of the World chess Championship were laid down.

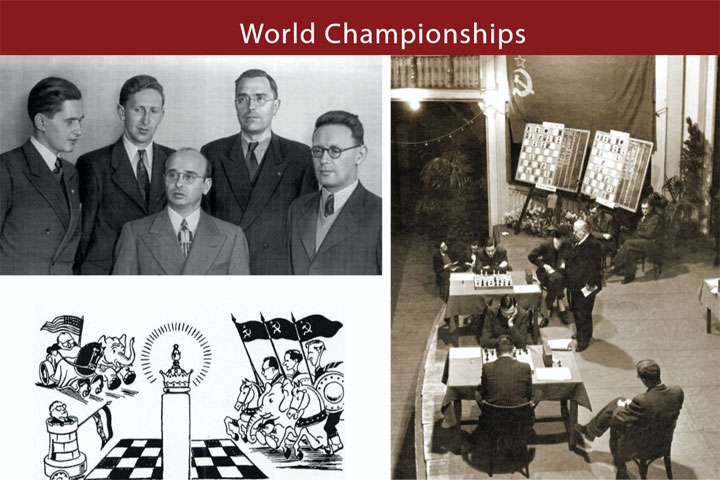

The General Assembly decided to confer the World Championship title on Max Euwe since he was the last unsuccessful challenger to Alexander Alekhine. However, the Assembly stipulated that he was to defend his title within a period still to be specified. The Assembly proposed a match for the FIDE World Chess Championship between Max Euwe as the champion against Samuel Reshevsky as the challenger. After this match, Paul Keres and Mikhail Botvinnik would play a match together, and then the winners of each match would meet for the World Chess Championship.

The Soviet delegation were not present when the Assembly started due to a bad connection and flight delay. When they arrived, the Assembly was treated to a long and impressive speech by Viacheslav Ragozin, and agreed to review the regulations. The final agreement, drafted on September 18, 1946, included a tournament of six players, organized in the Netherlands and Russia.

A few months later, the American player Reuben Fine declined the invitation for professional reasons; the Russians objected to the participation of Miguel Najdorf, although he had won in Prague. With the world championship tournament being reduced to five players, it was agreed that the first ten rounds would be played at The Hague and fifteen more at Moscow. The contestants would meet each other twice in Holland and three times in Russia for fifty games.

The first world championship tournament after WWII started in The Hague on March 1, 1948, with a prize fund of 13,000 US$. On March 25, the Dutch portion of the match concluded with Mikhail Botvinnik leading with 6 points ahead of Samuel Reshevsky, 4½.

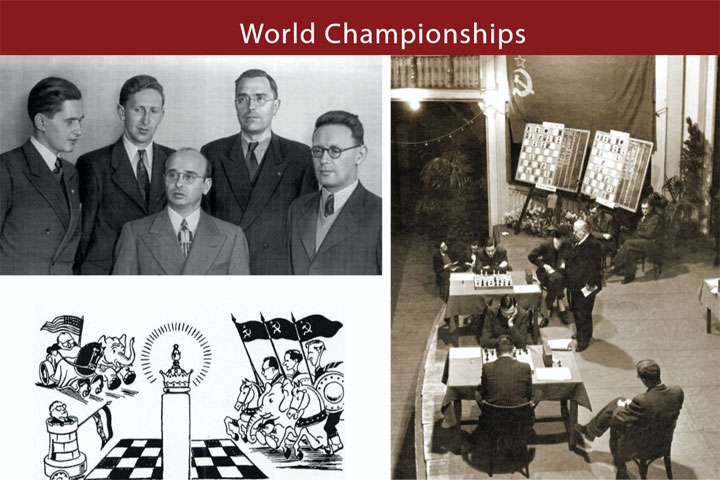

The playing hall of the 1948 World Championship in The Hague

The playing hall of the 1948 World Championship in The Hague

The tournament resumed in Moscow two weeks later, with 2000 spectators daily. After the 25th round, Mikhail Botvinnik won the title of world champion with 14 points ahead of Vasily Smyslov with 11, Samuel Reshevsky and Paul Keres with 10½, and Max Euwe with 4 points.

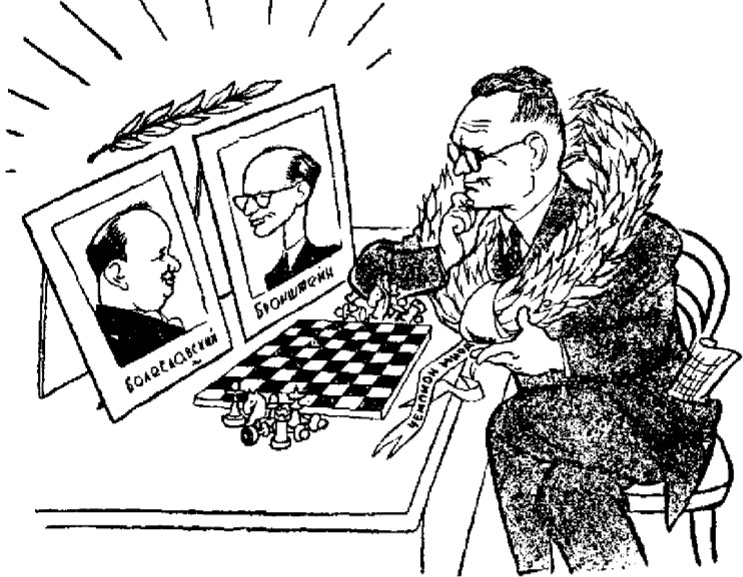

In 1950 the first Candidates Tournament was organized in Budapest with ten participants qualifying, including seven Soviet players. David Bronstein and Isaac Bolevslavsky finished equal first, and as per regulations, they went on to play a match in Moscow to decide the cycle’s winner. By the small margin of one little point, David Bronstein got his ticket to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik for the world title.

In 1950 the first Candidates Tournament was organized in Budapest with ten participants qualifying, including seven Soviet players. David Bronstein and Isaac Bolevslavsky finished equal first, and as per regulations, they went on to play a match in Moscow to decide the cycle’s winner. By the small margin of one little point, David Bronstein got his ticket to challenge Mikhail Botvinnik for the world title.

Moscow was the venue of the 1951 world championship between Mikhail Botvinnik and David Bronstein. As per the new FIDE regulations, the match for the title consisted of 24 games. In the event of a 12:12 draw, the champion would retain his title. The world champion Mikhail Botvinnik was lucky to win game 23 and draw game 24 to equalize the score and keep his title for another three years.

Further excerpts from 100 Years of FIDE to follow soon.

How to get the book: The easiest way to purchase the book is at Schach Niggemann, where it is available for €60.00.

Description: The book features images, many rarely seen before, along with details of events, organizers, players, arbiters, and key dates in the modern history of chess, all meticulously compiled by Willy Iclicki and Dmitry Oleynikov.

As you go through the pages, remember that behind every story or event described in this book are thousands of hours of work, on and off the chessboard, by enthusiasts from different eras, cultures, and backgrounds, all united by their love of chess. The chess world is deeply indebted to all of these people who have enriched the beauty and history of our game and elevated chess to new heights of global appreciation and respect. This book is also a celebration of them.

| Advertising |