The FIDE President and the Actress

By Edward Winter

The only screen goddess lucky enough to marry a FIDE President was Viveca

Lindfors (1920-1995), the sometime wife of Folke Rogard (1899-1973). Although

he has been largely forgotten today, from 1947 to 1970 he held the presidency

of the World Chess Federation and was much praised for his political skills.

Viveca Lindfors and Folke Rogard

In the Winter 1995 issue of Kingpin

we reported, courtesy of Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden), that the couple had

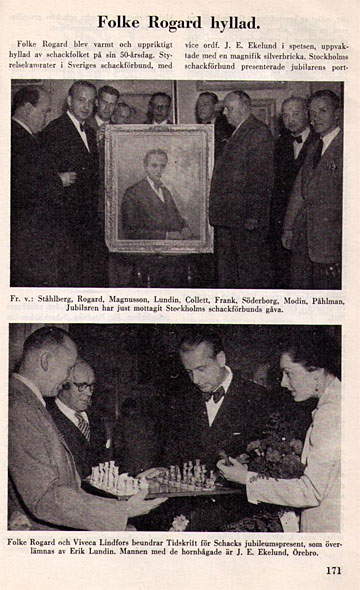

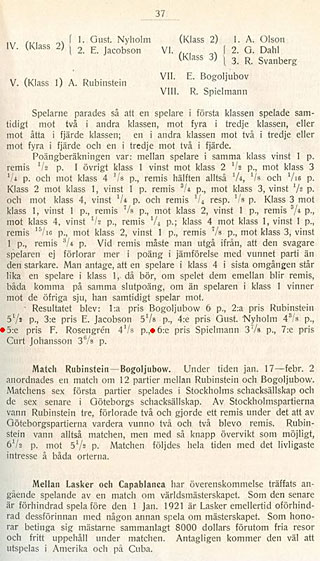

been featured on page 171 of the July-August 1949 issue of Tidskrift för

Schack. Below is the item in question, kindly provided by Mr Erlandsson:

Our correspondent also mentioned that the actress’s memoirs, entitled

Viveka...Viveca..., were published by Bonniers in Sweden in 1978. Page

93 related that when she wed Rogard in 1944 he changed his surname, and page

124 explained why:

‘It was a shock for [F.R.] when his brother was jailed for theft. Folke

was a successful young lawyer and very fearful for his reputation. He decided

to move with all the members of his family to another town, whether they wanted

to or not. He changed his name from Rosenberg to Rogard and cut all bonds.’

Mr Erlandsson pointed out that Rosenberg should read Rosengren. At the age

of seven or eight V.L. had changed her first name from Viveka to Viveca.

On page 135 the Swedish book related the couple’s ten-day visit to New

York in March 1946 to sign contracts before they went to Hollywood:

‘Folke did not assist me very much. He read, he slept, he ate, he drank

wine, he smoked cigars. He did not care about his appearance. He even played

chess against himself and took care of his leisure time much better than I

did mine. However, for him nothing was at stake.’

An English-language edition of the memoirs was published, under the same title,

by Everest House, New York in 1981. It was not identical to the Swedish original

(for instance, the above-quoted reference to chess was missing – see page

139), but much information about Rogard was still provided. From page 102 of

the English edition (referring to 1942):

‘... Folke, a politically aware man who had negotiated many deals with

the Nazis, representing rich Jews, buying freedom for them and their relatives.’

On page 127 she described him as ‘this enormous man in size, in voice,

in action ...’

A rare mention of chess came on page 139:

‘I watched him on the train playing chess with himself, envying him

for dealing so much better than I with his leisure time.’

Divorce followed, and she later married the actor and writer George Tabori.

Her book has ‘the first picture of the Tabori-Lindfors family in the house

on 95th Street’:

We possess several inscribed copies of Viveka ... Viveca, and her handwriting

was particularly large and florid:

Viveca Lindfors may be best known for her role as Queen Margaret opposite Errol

Flynn (1909-1959) in a film made in the late 1940s, Adventures of Don Juan.

Below, also from our collection, is a photograph of the couple inscribed by

her:

We subsequently noted in Kingpin that although Flynn is chiefly remembered

for his swashbuckling films and off-screen embroilments, he was also a vividly

eloquent novelist and journalist and received a brief mention on page 79 of

the 14 November 1937 issue of CHESS: ‘Errol Flynn is another film-star

chess-ite.’ Page 61 of Errol Flynn in Northampton by Gerry Connelly

(Corby, 1995) reported:

‘Flynn might not have been an Einstein or a Socrates, but he always

took intelligent approaches to his film rôles, played chess well, could

converse in a number of exotic languages, and worked productively as a writer.’

Flynn himself took lightly the claims made on his behalf. In an article entitled

‘My Plea for Privacy’ published in Screen Guide in 1937 he

wrote:

‘As to my private life – well, there’s precious little

of it left – but according to what I read in the newspapers, I am a

master of such minor arts as boxing, fencing, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, horsemanship,

hunting, fishing, sailing, swimming, golf, tennis, chess, trap-shooting and

jacks. I get up early in the morning and after dashing through Beethoven’s

Etude in B Minor I casually practise each and every one of the above

sports, sometimes doing a little Indian club work with my disengaged hand.’

A photograph of Errol Flynn playing chess appeared in the book From a Life

of Adventure: The Writings of Errol Flynn edited by Tony Thomas (Secaucus, 1980). Taken during the shooting of his 1942 film They Died with Their

Boots On, it showed him locked in combat with Olivia de Havilland:

Finally regarding Flynn, below is a large photograph in our collection, signed

by him in 1940:

Returning now to Folke Rogard, we give this quote: ‘One shudders to think

what FIDE would have been without him.’ That was Harry Golombek’s

verdict (BCM, December 1970, page 345) when Rogard retired as President

of the governing body and handed over to Max Euwe. Golombek also commented that

the choice of successor ‘was unanimous and certainly no better man (or

even as good) could be found to fill the place vacated by Folke Rogard after

21 years’ magnificent service in this post’.

In his obituary in The Times (later reproduced on pages 513-514 of the

December 1973 BCM and partly used in his 1977 Encyclopedia) Golombek

wrote of Rogard:

‘... in 1949 he succeeded the kindly, but not particularly effective

Dutchman, Dr Rueb, in the post of President of FIDE. He at once set to and

busied himself with the task of first of all bringing such great chess-playing

countries as the USSR and West Germany into the FIDE fold and then of asserting

the authority of the parent body over all the national units that were affiliated

to it.

He brought to the task an ideal temperament, consisting of an iron will-power

encased in a velvet glove. Quite a good actor, he would seem to explode with

rage when he thought it necessary to blast away unwarranted opposition; but

underneath he remained as cool as a cucumber. He and only he was able to come

between the clash of mighty opposites in the shape of the USSR and the USA

and by observing a strict neutrality he was able to reconcile the very different

aims of East and West.’

There follows a selection of photographs of Folke Rogard gleaned from chess

publications:

Rogard spectating at a game in the 1947 Swedish championship (Chess Review,

September 1947, page 5)

Rogard (standing on the left) watching a lightning game between G. Stoltz and

V. Smyslov in Sweden

(Chess Review, December 1951, page 355)

At the 1953 Candidates’ tournament in Switzerland (from Schach-Elite

im Kampf)

From page 19 of XIV. Schach-Olympiade Leipzig 1960

V. Korchnoi, C.A. Andersson (Stockholm city official), F. Rogard and R.J. Fischer

at the

Stockholm Interzonal Tournament (Chess Review, April 1962, page 104)

Opening of the Tel Aviv Olympiad (Chess Life, December 1964, page 291).

Folke Rogard did not claim to be an especially strong player, and it might

easily be assumed that no games of his are extant. However, it was mentioned

earlier that his former surname was Rosengren (or Rosengrén), and Calle

Erlandsson has pointed out to us that a player with that rare name (and, moreover,

with F. as the initial of his forename) participated in a tournament held in

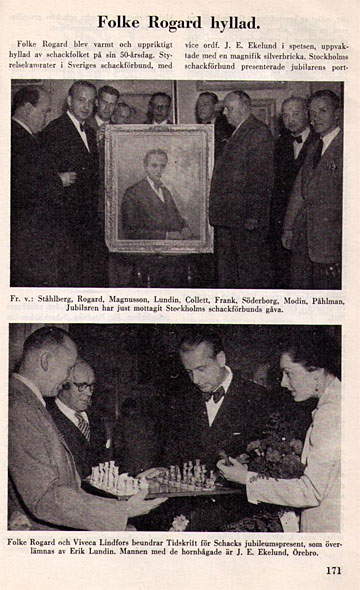

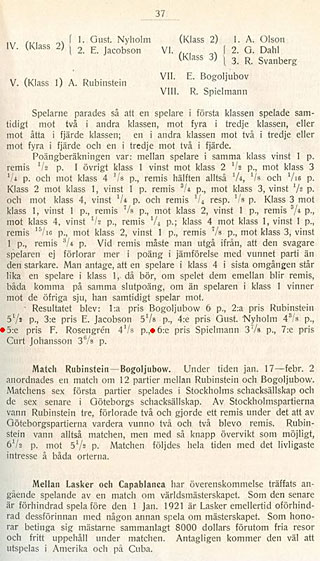

Stockholm from 27 December 1919 to 4 January 1920. This report was published

on pages 36-37 of the January-March 1920 Tidskrift för Schack:

The event was a handicap tournament played in accordance with the so-called

Collijn system. The Swedish magazine supplied none of Rosengren’s games,

but Mr Erlandsson also notes that the game-score of ‘Rubinstein –

Rosengren’ was given, though without mention of the name Rogard, on pages

377-379 of volume one of The Life & Games of Akiva Rubinstein by

J. Donaldson and N. Minev (Milford, 2006). The source was specified on page

379 as ‘scoresheet from Littorin archive’, and thanks to Peter Holmgren

(Stockholm) it can be reproduced here:

Below is the transcript of the game (in which Rubinstein was White) as it appeared

in the Donaldson/Minev book:

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 cxd5 4 Bd3 Nf6 5 c3 Bg4 6 Qb3 Qc7 7 f3 Bh5 8 Ne2 Bg6

9 Bf4 Qd7 10 Bxg6 hxg6 11 Nd2 Nc6 12 O-O e6 13 Rfe1 Na5 14 Qc2 Bd6 15 Nf1 Bxf4

16 Nxf4 Rh6 17 Nd3 Nc6 18 a4 Qc7 19 Re2 Ke7 20 Rae1 Rah8 21 g3 Rc8 22 Qb3 Kf8

(The 22nd moves are missing from the scoresheet.) 23 Nc5 b6 24 Nd3 Kg8 25 Ne3

Rd8 26 Nf2 Qe7 27 Qb5 Qd7 28 Nfg4 Nxg4 29 Nxg4 Rh5 30 f4 Nb8 31 h4 Qd6 32 Ne5

a6 33 Qd3 Rh6 34 Kg2 a5 35 g4 Rxh4 36 Kg3 Rh6 37 g5 Rh5

38 Nxf7 Kxf7 39 Rxe6 Rxg5+ 40 Kf3 Rh8 41 Rxd6 Rh3+ 42 Kf2 Resigns.

Folke Rogard (Livre d’or de la FIDE)

Submit information

or suggestions on chess explorations

All articles by Edward

Winter

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then over

5,900 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then over

5,900 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing

in its archives

will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes

and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from

around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary

readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent

masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess

History Center. Signed copies of Edward Winter's publications are

currently available.

Edward

Winter is the editor of

Edward

Winter is the editor of