Chess Explorations (14)

By Edward Winter

In each of six positions the challenge was to find which move White played.

To assist, it was mentioned that all the games had been featured in Chess Notes

over the past four years or so. There were some excellent entries, and below

we provide the solutions.

Position 1:

White played 22 Re8.

This was the most straightforward of the six positions, and 22 Re8 may be described

with the oxymoron ‘a standard brilliancy’. The game was given in

C.N. 3773, from the American Chess World (July 1901 issue, page 146), an undated

victory by A.W. Fox against A. Clerc at the Café de la Régence in Paris:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Qe2 Nd6 7 Bxc6 bxc6 8 dxe5

Nb7 9 Nc3 O-O 10 Be3 Nc5 11 Bxc5 Bxc5 12 Ne4 Be7 13 Rad1 a5 14 Rfe1 a4 15 Nd4

Qe8 16 Qh5 Kh8 17 Nf6 Bxf6 18 exf6 Qd8 19 fxg7+ Kxg7 20 Nf5+ Kh8 21 Qh6 Rg8

22 Re8 Resigns. [Click to

replay]

The circumstances surrounding other victories by Fox during that period are

unclear. See our feature article The Fox Enigma.

Albert Whiting Fox

Position 2:

White played 11 Nc4+.

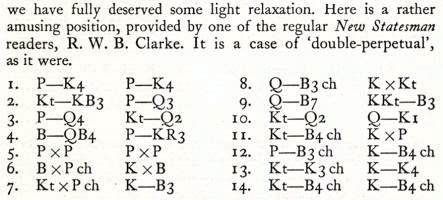

An extract from page 61 of The Pleasures of Chess by Assiac (New York,

1952) was provided in C.N. 5647:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nd7 4 Bc4 h6 5 dxe5 dxe5 6 Bxf7+ Kxf7 7 Nxe5+ Kf6 8 Qf3+

Kxe5 9 Qf7 Ngf6 10 Nd2 Qe8 11 Nc4+ Kxe4 12 f3+ Kf5+ 13 Ne3+ Ke5 14 Nc4+ Kf5+

Drawn. [Click to replay]

No further details have been found, and we are still looking for any other

games which finished with what Assiac termed ‘double-perpetual’.

Position 3:

White played 25 Nf4.

C.N. 3497 discussed this position, from Důras v Olland, Carlsbad, 1907.

Our item quoted D.J. Morgan on page 248 of the September 1953 BCM:

‘You will frequently find the same error repeated in book after book.

Thus, in this position, du Mont’s The Basis of Combination in Chess,

Korn’s The Brilliant Touch and Richter’s Kombinationen

all give a polished finish with 1 Bf8+ Bh5 2 Qxh5+ gxh5 3 Rh6 mate. The score

of the game (see, for instance, The Year-Book of Chess, 1908) shows

that Důras actually won more prosaically with 1 Nf4 Rh8 2 Nxd5 Qxd6 3

exd6 Bh5 4 Be3 Rad8 5 Qg5 Resigns.’ [Click

to replay]

We added that the Carlsbad, 1907 tournament book (page 107) reported that the

quick mate had been indicated by Victor Tietz:

C.N. 3497 also commented that the queen sacrifice continues to be presented

as if it occurred in actual play. Such is specifically stated in, for example,

Checkmate! (subtitle: My first chess book) by G. Kasparov (London,

2004). See pages 58 and 86, where the diagrams also have an additional rook,

on f1.

Oldřich Důras

Position 4:

White played 33 Rf6+.

In this position too White (the then world champion, Lasker) missed the fastest

win, which was an unusual mate in three: 33 Qg6+ Kxd5 34 Rf6, etc. We found

the game on page 10 of the third section of the New York Sun, 8 May 1910

and gave it in C.N. 5171:

Emanuel Lasker (simultaneous) – A.B. Yurka and G. Goldenberg

New York, 25 April 1910

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 Bxe7 Qxe7 7 Qd2 a6 8 Nd1 c5

9 c3 Nc6 10 f4 b5 11 Nf3 Bb7 12 Bd3 c4 13 Bc2 Nb6 14 Ne3 b4 15 O-O g6 16 Rf2

Qf8 17 Raf1 bxc3 18 bxc3 Qa3 19 Rb1 Qa5 20 Ng4 Ra7 21 Nf6+ Ke7 22 Ng5 h6 23

Nxf7 Kxf7 24 Bxg6+ Kxg6 25 f5+ exf5 26 g4 Bc8 27 gxf5+ Bxf5 28 Rbf1 Ne7 29 Rxf5

Nxf5 30 Qg2+ Kf7 31 Rxf5 Raa8 32 Nxd5+ Ke6 33 Rf6+ Resigns. [Click

to replay]

Emanuel Lasker

Position 5:

White played 27 e8(Q).

The game in question, between L. Trent and D. Tan, was played in a 2002-2003

league match in London (Barbican 4NCL 2 v Wood Green): 1 d4 Nf6 2 Bg5 e6 3 e4

h6 4 Bxf6 Qxf6 5 Qd2 d5 6 Nc3 c6 7 O-O-O Bb4 8 e5 Qd8 9 a3 Be7 10 f4 a5 11 Nf3

b5 12 a4 Bb4 13 Qe3 Bxc3 14 Qxc3 bxa4 15 h4 Qb6 16 Rh3 Ba6 17 Rg3 O-O 18 f5

exf5 19 Qe3 Kh8 20 e6 f6 21 e7 Re8 22 Ne5 Ra7 23 Rxg7 Kxg7 24 Qg3+ Kh8 25 Nf7+

Kh7 26 h5 Rg8 27 e8(Q) Resigns. [Click

to replay]

C.N. 4826 discussed the conclusion. The game was annotated on pages 20-21 of

issue 37 of Kingpin,

where Jonathan Rogers’ final comment reads:

‘A novel situation, as far as I know. Has anyone before seen a serious

game where one side has two queens, both en prise and unprotected even,

to the same enemy piece, with each queen being able to deliver mate in one

upon the capture of the other?’

Position 6:

White played 36 Bg5.

Although it may appear that White has no chance of saving the game, some trickery

enabled him to draw. C.N. 5145 quoted the account of what happened from pages

24-25 of Not Only Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1974):

‘... Cold-blooded gamesman-planning is rare. But I have one pretty

example. At my first British Championship, [at Ramsgate] in 1929, a friend

of mine – who is a magnificent analyst and celebrated in the chess world

– found himself in a very bad position. But there was a way out. Given

that his opponent (a very strong player) did not see the threat, it was possible,

with a series of sacrifices, to achieve stalemate. But he had to include in

his play a clearly inadequate move, which would inevitably warn his opponent.

After all, one plays chess on the assumption that the opponent sees everything.

(That is why the word “trap” is not a good chess term.) But my

friend devised a psychological trap. He sat and looked at the board with a

despairing face until he was well and truly in time trouble. Then he fumblingly

made the crucial moves. His opponent, tempted to a little gamesmanship himself,

was playing very quickly. Quick came the erroneous capture. Even quicker came

the series of sacrifices and, while the flag was tottering, stalemate supervened.

Now could he have improved on things in the following way: touched the piece,

taken his hand away, and let himself be compelled to move the piece at random?

No, he had thought of that, but dismissed it as sharp practice.’

Abrahams then gave the relevant position:

‘Time control at move 40. At move 31 Black has played R-Kt6, a good

move, because, if either rook guards the bishop, RxB wins.’

Play continued: 32 Bd2 Rg3+ 33 Kh1 Rxh3+ 34 Kg1 Rd3 35 Bc1 (‘Leaving

himself less than half a minute on his clock.’) 35...Rc7 36 Bg5 (‘Finger

staying on his clock; and Black falls for it.’) 36...Rg3+ 37 Kh1

37...Rxg5 38 R1f7+ Rxf7 39 Rxf7+ (‘Forcing stalemate or perpetual check.’).

[Click to replay]

Abrahams did not name the players, but C.N. 5145 noted that the position after

White’s 37th move was given on page 346 of the September 1929 BCM.

W.A. Fairhurst was White against T.H. Tylor.

For similar deeds, see the entry for ‘Cunning, gamesmanship and skulduggery’

in our Factfinder.

The main prize in the competition is Winning Chess Combinations by Yasser

Seirawan (London, 2006), personally inscribed to the winner by Seirawan. It goes to Samuel Stolpe (Alexandria, VA, USA).

Yasser Seirawan, the co-inventor of Seirawan

Chess

The two consolation prizes, a pocket-sized book on Magnus Carlsen (Kecskemét,

2008), signed by Carlsen, have been won by Gwénolé Grall (Douarnenez, France) and Gábor Gyuricza (Budapest, Hungary).

Submit information

or suggestions on chess explorations

All articles by Edward

Winter

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then over

5,900 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then over

5,900 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing

in its archives

will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes

and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from

around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary

readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent

masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess

History Center. Signed copies of Edward Winter's publications are

currently available.

Edward

Winter is the editor of

Edward

Winter is the editor of