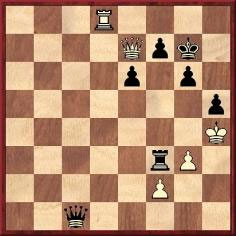

C.N. 1301 gave a position from the game A. Steiner v L. Prins at the 1936 Olympiad in Munich, from page 81 of Olympische Blitzsiege by E.J. Diemer (published in Kecskemét and undated):

Black has just played 31...Nd7-f8, and White replied 32 Nxh5, instead of giving immediate mate. The book, which made no mention of the possibility, gave the game-score as follows: 1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 c3 e6 5 Nd2 Nb8 6 g4 Bg6 7 Nh3 c5 8 Nf4 Qc7 9 h4 cxd4 10 Bb5+ Kd8 11 cxd4 Bc2 12 Qf3 Ne7 13 Nh3 Nec6 14 Qc3 Be4 15 O-O Bb4 16 Qe3 Bxd2 17 Bxd2 h5 18 Be2 Qb6 19 Bc3 Ne7 20 b4 Nbc6 21 b5 Nb8 22 Rfc1 Ke8 23 Bb4 Nd7 24 Qc3 Qd8 25 Qc7 Nc6 26 Qxd8+ Nxd8 27 f3 Bh7 28 Rc7 b6 29 Rac1 f6 30 exf6 gxf6 31 Nf4 Nf8 32 Nxh5 Nf7 33 Ng7+ Resigns.

In a letter to us dated 22 October 1987 the late Lodewijk Prins wrote:

‘I cannot explain Steiner’s overlooking a mate in one. If the diagrammed position is correct, both sides must have been extremely short of time, I should think.’

Do any other sources suggest a different game-score?

Lodewijk Prins

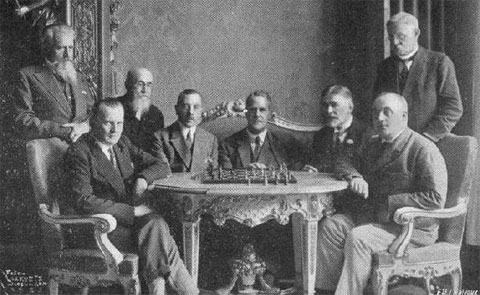

This photograph, given in C.N. 4237, was published as a supplement to the January 1930 issue of L’Echiquier. Alexander Alekhine and Efim Bogoljubow are seated in the foreground and the FIDE President, Alexander Rueb, is in the centre. Who are the others?

C.N. 52 gave the following piece of play and asked if the full game-score was available, but nothing more has yet been found.

‘Lazdies v Zenitas, Riga, 1936’

White is said to have played 1 Qf8+ Kf6 2 Qh8+ Kf5 3 g4+ hxg4 4 Rd5+ exd5 5 Qc8+ Drawn.

We took the position from page 64 of The Pleasures of Chess by Assiac (New York, 1952), but another secondary source, page 268 of Kurzgeschichten um Schachfiguren by Kurt Richter (Hollfeld, 1991), gave the players’ names as Lazdiņš and Zemītis and the date as 1935.

From page 129 of the April 1930 BCM:

‘A very interesting meeting of the Executive Committee of the British Chess Federation was held in London, on 8 March. Major Sir Richard Barnett, who was in the chair, very kindly offered to purchase and present to the Federation an oil painting of Howard Staunton, dated 1846 ...’

This report was briefly mentioned in C.N. 1136, but no further information about the portrait has come to our attention. Do readers have any details?

We have often discussed positions in which a player moved his queen to KKt6 (i.e. g6 or g3) when the opponent had three unmoved pawns before his castled king, and our findings have been summarized in the feature article The Fox Engima.

Although only ten games have so far been found which contain the queen sacrifice, two of them were allegedly won by the same player, A.W. Fox, in quick succession:

Positions before Fox played 18 Qxg6 and 21 Qg6. |

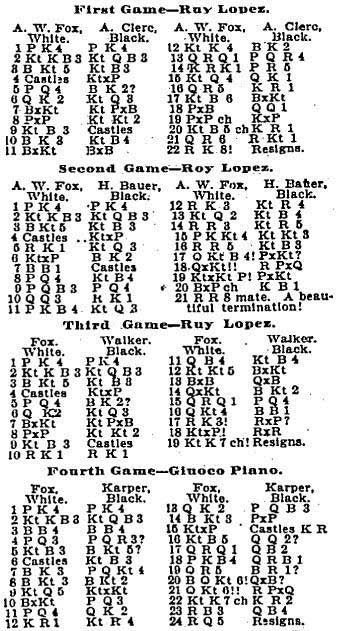

Indeed, as Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) pointed out in C.N. 4409, both game-scores appeared on page 20 of the Chicago Tribune of 12 May 1901 (games two and four):

Is this a remarkable, genuine coincidence or is something darker afoot?

Relatively little information is available about how the Swiss System originated, and in C.N. 4118 Richard Forster (Zurich) summarized what is currently known:

‘When did the Swiss System obtain its name and when was it invented? The standard reference works mention that it was introduced by Dr Julius Müller of Brugg at the 1895 Swiss Championship in Zurich.

Julius Müller (1857-1917) was a meteorologist and teacher in Brugg (not far from Zurich). He was a founding member of the Swiss Chess Federation in 1889, and a member of the committee and then treasurer until 1903, when he was elected an honorary member. The Swiss pairing system, the official magazine (Schweizerische Schachzeitung) and many other sparkling ideas are credited to him (as noted in his obituary in the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, July 1917, page 103).

The Swiss system was created for the Swiss chess congresses which, starting in 1889 in Zurich, usually packed four or five rounds into two or three days (plus a problem-solving contest, a general assembly and a banquet). As is shown by the tournament regulations (Turnier-Ordnung), during the first few years a prototype of the modern system was used: after each round the field was, according to the results of the previous round, divided into two groups, winners and losers, who were then paired among each other by lot. In case of a draw it was decided by lot who would belong to the “winners” and who to the “losers”. Only at the very end were the points gained added together to ascertain the final ranking. Whether or not attention was paid to equal colour distribution is unknown, and we do not know for sure whether the same two players could be paired against each other more than just once. In the third edition, for instance, two players won with 4/4 in a field of 16; this would not be possible under today’s system because they would have met in the fourth round at the latest.

For the ninth congress (Lausanne, 1899) the rules were changed so that players with an equal number of points were paired against each other, but in case of a draw one player was still counted as the “winner” and the other as the “loser”. Only in the rules for the St Gallen congress (1901) was it stated that the actual number of points was the sole criterion for pairing.

This does not exclude the possibility that the pairings were handled in the modern way long before the St Gallen tournament (after all, the members of the pairing committee were presumably always the same), but it still leaves open the question of why the 1895 tournament is commonly singled out as marking the birth of the Swiss System.

Incidentally, in 1940 Erwin Voellmy referred to Julius Müller as the inventor of the “Swiss (or sometimes Danish) pairing system” (Schweizerische Schachzeitung, May 1940, page 71). What is known about these Danish roots of the Swiss System?’

In C.N. 3815 Joshua B. Lilly (Martinsville, VA, USA) raised the subject of a famous game, Rossolimo v Livingstone, New York, 1961, asking for specifics as to a contemporary source, the occasion and Black’s identity:

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qa5 4 d4 Nf6 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 h3 Qh5 7 Be2 Nc6 8 O-O Bxh3 9 gxh3 Qxh3 10 Ng5 Qh4 11 d5 Ne5 12 Bb5+ c6 13 dxc6 bxc6 14 Nd5 O-O-O 15 Ba6+ Kb8 16 Bf4 Rxd5 17 Bxe5+ Ka8

18 c4 Qxg5+ 19 Bg3 Rxd1 20 Raxd1 Nd5 21 cxd5 c5 22 b4 c4 23 Rd4 e5 24 dxe6 Bxb4 25 Rd7 Rb8 26 Rfd1 Be7 27 exf7 c3 28 f8(Q) Resigns.

Jack O’Keefe (Ann Arbor, MI, USA) responded in C.N. 4047:‘I have part of an answer to the mystery of the Rossolimo v Livingstone game. It was published in B.H. Wood’s column in the Illustrated London News, 30 December 1961, page 1160. His introduction to the game was:

“N. Rossolimo, born in Odessa of Greek parentage, wandered to Prague, then Paris. He is now in New York. Here is a real Wild West game he played there recently.”

Wood wrote nothing further about the occasion or the opponent. However, Chess Life for 1961 gives no tournaments in which Rossolimo took part, and it seems likely that the game was not played in a serious event.’

Can any further particulars be discovered?

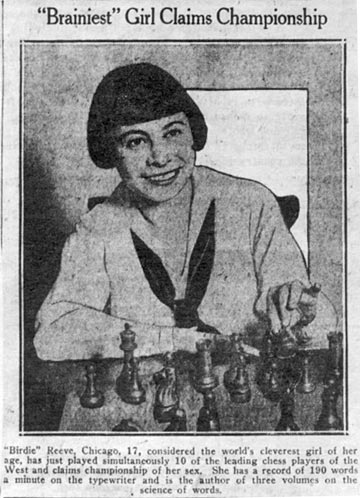

Birdie Reeve

A number of C.N. items (as listed in our Factfinder) have discussed the so-called chess prodigy Birdie Reeve. C.N. 3572 noted that page 81 of The Gambit, March 1928 reproduced the following from an unidentified publication:

The caption reads:

‘“Birdie” Reeve, Chicago, 17, considered the world’s cleverest girl of her age, has just played simultaneously 10 of the leading chess players of the West and claims championship of her sex. She has a record of 190 words a minute on the typewriter and is the author of three volumes on the science of words.’

‘Miss Birdie Reeves [sic], one of the best women chess players in America, was also on the scene during the major part of the performance and furnished excellent entertainment for the gathering of fans.’

That event, a Washington v London cable match on 10 November featuring such players as Mlotkowski, Whitaker, Yates and Michell, was the subject of reports on page 182 of the December 1928 American Chess Bulletin and pages 441-443 of the December 1928 BCM, but they made no mention of Birdie Reeve.

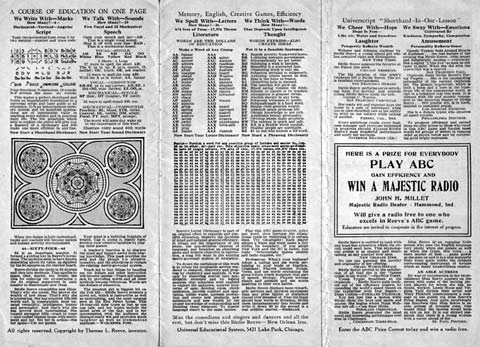

C.N. 3647 mentioned that we had acquired a promotional leaflet (no year indicated) for one of Birdie Reeve’s exhibitions. It included a photograph of her ostensibly giving a simultaneous display:

Larger versions of side one and side two of the leaflet are provided for perusal (large files).

In the same C.N. item Jerry Spinrad reported that Birdie Reeve died of a heart attack on 31 May 1996 at the age of 89, and that her obituary was published on page 53 of the Chicago Sun Times, 3 June 1996. There was no mention of chess, and we have yet to find any reference to her in a chess magazine other than, as indicated above, the US publication The Gambit in 1928.

Submit information or suggestions on chess mysteries

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around

5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around

5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing in its archives will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess History Center.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (1)

14.02.2007 – Since Chess

Notes began, over 25 years ago, hundreds of mysteries and puzzles have

been discussed, with many of them being settled satisfactorily, often thanks

to readers. Some matters, though, have remained stubbornly unsolvable –

at least so far – and a selection of these is presented here. Readers are

invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (2)

12.03.2007 – We bring you a further selection

of intriguing chess mysteries from Chess

Notes, including the origins of the Marshall Gambit, a game ascribed

to both Steinitz and Pillsbury and the bizarre affair of an alleged blunder

by Capablanca in Chess Fundamentals. Once again our readers are invited

to join the hunt

for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (3)

27.03.2007 – Recently-discovered photographs

from one of Alekhine’s last tournaments, in Spain in 1945, are proving baffling.

Do they show that a 15-move brilliancy commonly attributed to Alekhine is

spurious? And do they disprove claims that another of his opponents was

an 11-year-old boy? Chess

Notes investigates, and once again our readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (4)

10.04.2007 – What would have happened if the

score of the 1927 Capablanca v Alekhine match had reached 5-5? Would the

contest have been declared drawn? The affair has been examined in depth

in Chess Notes.

Here chess historian Edward Winter sifts and summarizes the key evidence.

There is also the strange case of a fake photograph of the two masters.

Join

the investigation.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (5)

30.04.2007 – We bring you a further selection

of mysteries from Edward Winter’s Chess

Notes, including an alleged game by Stalin, some unexplained words attributed

to Morphy, a chess magazine of which no copy can be found, a US champion

whose complete name is uncertain, and another champion who has vanished

without trace. Our readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (6)

19.05.2007 – A further miscellany of mysteries

from Chess Notes is presented

by the chess historian Edward Winter. They include an alleged tournament

game in which Black was mated at move three, the unclear circumstances of

a master’s suicide, a chess figure who was apparently unaware of his year

of birth, the book allegedly found beside Alekhine’s body in 1946, and the

chess notes of the poet Rupert Brooke. Join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (7)

02.06.2007 – The chess historian Edward Winter

presents another selection of mysteries from Chess Notes. They include an

alleged game by Albert Einstein, the origin of the Trompowsky Opening, the

termination of the 1984-85 world championship match, and the Marshall brilliancy

which supposedly prompted a shower of gold coins. Readers are invited to

join in the hunt

for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (8)

In this further selection from Chess

Notes historian Edward Winter examines some unauthenticated quotes,

the Breyer Defence to the Ruy López, the origins of the Dragon Variation,

the contradictory evidence about a nineteenth century brilliancy, and the

alleged 1,000-board exhibition by an unknown player. Can our readers help

to solve these new

chess mysteries?

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (9)

Why did Reuben Fine withdraw from the 1948 world championship?

Did Capablanca lose an 11-move game to Mary Bain? Was Staunton criticized

by Morphy for playing ‘some devilish bad games’? Did Alekhine

play Najdorf blindfold? Was Tartakower a parachutist? These and other mysteries

from Chess

Notes are discussed by Edward Winter. Readers are invited to join in

the hunt

for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (10)

15.07.2007 – Did Tsar Nicholas II award the ‘grandmaster’

title to the five finalists of St Petersburg, 1914? What connection exists

between the Morphy family and Murphy beer? Can the full score of one of

Pillsbury’s most famous brilliancies be found? Did a 1940s game repeat

a position composed 1,000 years previously? Edward Winter, the Editor of

Chess

Notes, presents new

mysteries for us to solve.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (11)

01.08.2007 – Did Alekhine attempt suicide in 1922? Why is

1 b4 often called the Hunt Opening? What are the origins of the chess proverb

about the gnat and the elephant? Who was the unidentified figure wrongly

labelled Capablanca by a chess magazine? Does Gone with the Wind

include music composed by a chess theoretician? These and other mysteries

from Chess Notes

are discussed by the historian Edward Winter. Readers are invited to join

the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (12)

12.08.2007 – This new selection from Chess

Notes focuses on José Raúl Capablanca (1888-1942). The chess historian

Edward Winter, who wrote a book about the Cuban genius in the 1980s (published

by McFarland), discusses a miscellany of unresolved matters about him, including

games, quotes, stories and photographs. Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (13)

26.08.2007 – In a 1937 game did Alekhine play two moves in succession?

Can the full score of a Nimzowitsch brilliancy be found? Who was Colonel

Moreau? Why was it claimed that Morphy killed himself? Who were the first

masters to be filmed? What happened in the famous Ed. Lasker v Thomas game?

Is a portrait of the young Philidor genuine? From Chess

Notes comes a new selection of mysteries

to solve.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (14)

The latest selection from Chess

Notes consists of ten positions, including fragments from games ascribed

to Capablanca and Nimzowitsch. Was an alleged Bernstein victory a composition?

What is known about a position in which Black resigned despite having an

immediate win? Can more be discovered about the classic Fahrni pawn ending?

Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (15)

Chess books repackaged as camouflage in Nazi Germany. Numerous contradictions

regarding a four-move game. The chess encyclopaedia that never was. Quotes

strangely attributed to Spielmann and Capablanca. These and other mysteries

are discussed in the latest selection from Chess

Notes. Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (16)

Did Lasker invent a tank? Why did Mieses complain to FIDE about Bogoljubow?

What merchandising carried Flohr’s name? Who coined the term ‘grandmaster

draw’? What did Hans Frank write about Alekhine? Did Tom Thumb play

chess? These are just some of the questions discussed in the latest selection

from Chess Notes.

Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (17)

This further selection from Chess

Notes examines some gross examples of fraud and plagiarism in chess

literature. A number of books, for instance, have been published in Canada

and India under the names of Brian Drew, Frank Eagan, Thomas E. Kean and

Philip Robar, but did any of those individuals even exist? Readers are invited

to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (18)

An apparent missed mate in one at the 1936 Munich Olympiad; an

enigma regarding two Fox brilliancies; the origins of the Swiss System;

an untraceable painting of Staunton; the strange case of the prodigy Birdie

Reeve. These and other mysteries are discussed in a further selection from

Chess Notes.

Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.