Unsolved Chess Mysteries (13)

By Edward Winter

Two moves in succession

Page 588 of L. Skinner and R. Verhoeven’s book Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 (Jefferson, 1998) had the following comment in the section on Kemeri, 1937:

‘At one point during his game against Mikėnas, Alekhine accidentally made two moves in succession. Under the FIDE rules that were then in force, the tournament director, Hans Kmoch, could not enforce any penalty.’

Alexander Alekhine

As noted in C.N. 3202, this affair was mentioned similarly, although with no connection to the Mikėnas game, in a discussion of Alekhine’s play on page 6 of the tournament book by F. Reinfeld and S. Bernstein:

‘That he was still not quite his old self is seen in his poor play against Mikėnas, despite his heroic resistance later on in this game. This loss had a chastening effect on him, and subsequently he played with more care. The extent of his nervous preoccupation may be gauged from the fact that in one of his games he played two moves in succession. Hans Kmoch, the tournament director, was unable to invoke any penalty, as the playing rules say nothing about such a possibility.’

What can be discovered about this alleged incident?

Lund v Nimzowitsch

At present only the following fragment is available:

1...Rd5 2 Be3 Re5 3 Bf4 Rh5 4 Be3

4...b4 5 axb4 Rxh4 6 gxh4 g3 7 fxg3 c3+ 8 bxc3 a3 9 White resigns.

C.N. 2180 discussed this ending, from Leif Lund v Aron Nimzowitsch, Kristiania (i.e. Oslo), 6 May 1921 (a simultaneous display against 20 players). Is the full game-score traceable in, for instance, a local newspaper of the time? At present, all we have is Nimzowitsch’s account of the conclusion, from page 164 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 April 1925:

The finish had a succession of four breakthrough offers, and we wondered in C.N. 2180 if this was a record for sacrifices on consecutive moves. Subsequently, the game Cohn v Chiszar, featuring five sacrifices, was discussed (see pages 7-8 of Chess Facts and Fables).

Colonel Moreau

In C.N. 2434 the late Mike Franett requested information about Colonel Moreau, who lost all 26 of his games at Monte Carlo, 1903. The matter was also discussed in C.N.s 2459 and 2482, but little progress has been made so far.

On page 5 of Emil Kemeny’s American Chess Weekly, 29 April 1903, it was stated:

‘Colonel Moreau, who finishes last is perhaps stronger than the score would indicate, but he is not used to Tourney play, and too old to stand the continuous strain.’

The ‘perhaps’ is decidedly unflattering. The 22 April 1903 issue of La Stratégie, page 113, announced Moreau’s recompense for his 26 defeats: 75 francs. As regards his forename, page 47 of the February 1903 Wiener Schachzeitung (edited by Marco, a participant in the Monte Carlo tournament) had ‘Ch. [i.e. Charles] Moreau’.

Pages 175-176 of La Stratégie, 15 June 1874 gave a victory by Rosenthal at queen’s knight odds against a player named Moreau, and page 229 of the June 1900 BCM described the opening 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Nc6 as ‘a defence much exploited, if not invented by Mr C. Moreau, of London’. We also quoted some references from that period to ‘Mr C. Moriau’, who may or may not be the same person.

The list of 18 advance subscribers in Reinfeld’s 1935 book on Cambridge Springs, 1904 included C. Moreau, and our copy of Reinfeld’s book Thirty-five Nimzowitsch Games, 1904-1927 (New York, 1935) contains, handwritten, the subscriber’s name, C.A. Moreau. However, the list of subscribers on page 91 of Keres’ Best Games 1932-1936 (New York, 1937) by F. Reinfeld stated ‘C.L. Moreau’. Whether or not it was Colonel Moreau whom Reinfeld had among his subscribers is not known. It may seem unlikely, given that already in 1903 Moreau was described as ‘too old to stand the continuous strain’.

Page 51 of La Stratégie, 21 February 1903 stated that a Nice publication, Le Phare du Littoral, provided daily coverage of Monte Carlo, 1903 (results and games). Was any biographical information about Moreau included?

A claim that Morphy killed himself

C.N. 3384 quoted from page 33 of Morphy Gleanings by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1932):

‘I see no reason for the suggestion of some writers, including G.C. Reichhelm, that it was a case of suicide – by opening a vein, Reichhelm says.’

We are still seeking information on where Reichhelm, or any other writers, claimed that Morphy killed himself.

On the right: Gustavus Reichhelm (1839-1905), with Emanuel Lasker (Philadelphia, 1892)

On film

C.N. 2220 asked which was the first occasion when chess masters were filmed. The earliest case known to us is the New York, 1915 tournament. From page 91 of the May-June 1915 American Chess Bulletin:

‘… a genuine chess scene, and nothing less than the opening round of this tournament, was reproduced in motion pictures at various theaters throughout the country. On 17 April, on the invitation of the Messrs Pathé-Frères, the players, committee men and other prominent followers of the game repaired to the studio at the plant of that well-known concern and, under the direction of Mr Raymond J. Brown, the editor of Pathé News, posed before the camera which produced the films that were to make the public at large better acquainted with chess, and some of its chief exponents. In the principal sitting, the players were shown seated as paired in the opening round, making their moves, regulating clocks and recording scores, with officials and spectators grouped in the background. In addition, there were separate sittings for Capablanca and Marshall in individual poses.’

Film/news coverage of Carlos Torre and Samuel Reshevsky was discussed in C.N. 2535, which cited the following from page 176 of the November 1920

American Chess Bulletin:

‘According to H.A. Horwood of Los Angeles, Cal., in the October “Folder” of the Good Companion Chess Problem Club, Carlos Torre, R., the boy expert of New Orleans, like Rzeschewski, has appeared in the “movies”.’

The exact text in the source mentioned is given below:

‘H.A. Horwood, Los Angeles, Calif. “These are wonderful days for chess, as I saw last evening, in a moving picture theatre, an exhibition of our boy wonder, C. Reperto [sic], of New Orleans.”’

Source: “Our Folder”, 1 October 1920, page 11.

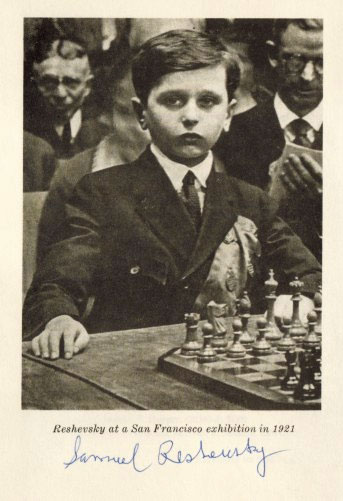

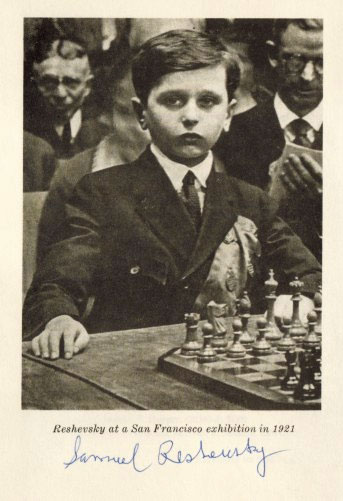

Samuel Reshevsky

What film of chessplayers is extant from the early years (e.g. before the well-known images from Moscow, 1925 in Chess Fever)?

Lasker v Thomas

A strong candidate for the most mysterious chess game (in terms of the number of different versions of the moves) is Ed. Lasker v George Thomas, London, 1912:

- 1) 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 Ne5 O-O (Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood by Edward Lasker, pages 117-123)

- 2) 1 d4 f5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Nf3 e6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7 (The World’s Great Chess Games by R. Fine, page 147 or pages 147-148 – editions vary)

- 3) 1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 e6 5 Nxe4 Be7 6 Bxf6 Bxf6 7 Nf3 O-O 8 Bd3 b6 9 Ne5 Bb7 (1000 Best Short Games of Chess by I. Chernev, page 272)

- 4) 1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7 (Schachjahrbuch für 1912 by L. Bachmann, pages 229-230)

- 5) 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Bg5 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7 (American Chess Bulletin, February 1918, page 28 – a feature by Edward Lasker)

- 6) 1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 Ne5 O-O (Chess Life, June 1981, page 17)

- 7) 1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 e6 5 Nxe4 Be7 6 Bxf6 Bxf6 7 Nf3 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7 (Europe Echecs, February 1965, page 20)

- 8) 1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 e6 5 Nxe4 Be7 6 Bxf6 Bxf6 7 Nf3 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 Ne5 O-O (Brilliance in Chess by G. Abrahams, pages 36-37).

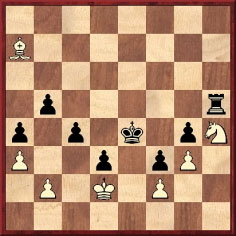

The same position is reached in all cases, and after the further moves 10 Qh5 Qe7 Edward Lasker played 11 Qxh7+ in this celebrated position:

Our feature article Chaos in a Miniature also chronicles many other discrepancies regarding the game, including several from the pen of Lasker himself. At least the date, 1912, is established, although on this point too all manner of things have been written. For example:

- ‘1910’: page 25 of The Daily Telegraph Chess Puzzles by David Norwood (London, 1995)

- ‘1911’: pages 88-89 of Queen Sacrifice by I. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1991)

- ‘1913’: page 239 of the September 1941 BCM

- ‘1913/1914’: page 89 of Şah Cartea de Aur by Constantin Ştefaniu (Bucharest, 1982)

- ‘1915’: pages 163-164 of How to Win in the Middle Game of Chess by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1955)

- ‘1921’: page 28 of 666 Kurzpartien by Kurt Richter (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966).

Ed. Lasker

A picture of Philidor?

A handful of old portraits of Philidor are known, but one alleged picture stands out as altogether different from the rest and was discussed in C.N. 3431. It was published on, for instance, page 47 of La fabuleuse histoire des champions d’échecs by N. Giffard (Paris, 1978) and on page 46 of volume 3 of Lademanns Skak Leksikon by S. Novrup (Copenhagen, 1982):

In C.N. 3448 Claes Løfgren (Randers, Denmark) pointed out that a colour version appeared on page 79 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974). Page 248 stated that it came from the Cleveland Public Library, but no further details have yet come to light.

Submit information or suggestions on chess mysteries

aficionados to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around 5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by Winter: Chess Explorations (1996), Kings, Commoners and Knaves (1999), A Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph on Capablanca (1989).

aficionados to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around 5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by Winter: Chess Explorations (1996), Kings, Commoners and Knaves (1999), A Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing in its archives will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess History Center.

Articles by Edward Winter

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (1)

14.02.2007 – Since Chess Notes began, over 25 years ago, hundreds of mysteries and puzzles have been discussed, with many of them being settled satisfactorily, often thanks to readers. Some matters, though, have remained stubbornly unsolvable – at least so far – and a selection of these is presented here. Readers are invited to join in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (2)

12.03.2007 – We bring you a further selection of intriguing chess mysteries from Chess Notes, including the origins of the Marshall Gambit, a game ascribed to both Steinitz and Pillsbury and the bizarre affair of an alleged blunder by Capablanca in Chess Fundamentals. Once again our readers are invited to join the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (3)

27.03.2007 – Recently-discovered photographs from one of Alekhine’s last tournaments, in Spain in 1945, are proving baffling. Do they show that a 15-move brilliancy commonly attributed to Alekhine is spurious? And do they disprove claims that another of his opponents was an 11-year-old boy? Chess Notes investigates, and once again our readers are invited to join in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (4)

10.04.2007 – What would have happened if the score of the 1927 Capablanca v Alekhine match had reached 5-5? Would the contest have been declared drawn? The affair has been examined in depth in Chess Notes. Here chess historian Edward Winter sifts and summarizes the key evidence. There is also the strange case of a fake photograph of the two masters. Join the investigation.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (5)

30.04.2007 – We bring you a further selection of mysteries from Edward Winter’s Chess Notes, including an alleged game by Stalin, some unexplained words attributed to Morphy, a chess magazine of which no copy can be found, a US champion whose complete name is uncertain, and another champion who has vanished without trace. Our readers are invited to join in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (6)

19.05.2007 – A further miscellany of mysteries from Chess Notes is presented by the chess historian Edward Winter. They include an alleged tournament game in which Black was mated at move three, the unclear circumstances of a master’s suicide, a chess figure who was apparently unaware of his year of birth, the book allegedly found beside Alekhine’s body in 1946, and the chess notes of the poet Rupert Brooke. Join in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (7)

02.06.2007 – The chess historian Edward Winter presents another selection of mysteries from Chess Notes. They include an alleged game by Albert Einstein, the origin of the Trompowsky Opening, the termination of the 1984-85 world championship match, and the Marshall brilliancy which supposedly prompted a shower of gold coins. Readers are invited to join in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (8)

In this further selection from Chess Notes historian Edward Winter examines some unauthenticated quotes, the Breyer Defence to the Ruy López, the origins of the Dragon Variation, the contradictory evidence about a nineteenth century brilliancy, and the alleged 1,000-board exhibition by an unknown player. Can our readers help to solve these new chess mysteries?

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (9)

Why did Reuben Fine withdraw from the 1948 world championship? Did Capablanca lose an 11-move game to Mary Bain? Was Staunton criticized by Morphy for playing ‘some devilish bad games’? Did Alekhine play Najdorf blindfold? Was Tartakower a parachutist? These and other mysteries from Chess Notes are discussed by Edward Winter. Readers are invited to join in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (10)

15.07.2007 – Did Tsar Nicholas II award the ‘grandmaster’ title to the five finalists of St Petersburg, 1914? What connection exists between the Morphy family and Murphy beer? Can the full score of one of Pillsbury’s most famous brilliancies be found? Did a 1940s game repeat a position composed 1,000 years previously? Edward Winter, the Editor of Chess Notes, presents new mysteries for us to solve.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (11)

01.08.2007 – Did Alekhine attempt suicide in 1922? Why is 1 b4 often called the Hunt Opening? What are the origins of the chess proverb about the gnat and the elephant? Who was the unidentified figure wrongly labelled Capablanca by a chess magazine? Does Gone with the Wind include music composed by a chess theoretician? These and other mysteries from Chess Notes are discussed by the historian Edward Winter. Readers are invited to join the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (12)

12.08.2007 – This new selection from Chess Notes focuses on José Raúl Capablanca (1888-1942). The chess historian Edward Winter, who wrote a book about the Cuban genius in the 1980s (published by McFarland), discusses a miscellany of unresolved matters about him, including games, quotes, stories and photographs. Readers are invited to join in the hunt for clues.

- Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (13)

26.08.2007 – In a 1937 game did Alekhine play two moves in succession? Can the full score of a Nimzowitsch brilliancy be found? Who was Colonel Moreau? Why was it claimed that Morphy killed himself? Who were the first masters to be filmed? What happened in the famous Ed. Lasker v Thomas game? Is a portrait of the young Philidor genuine? From Chess Notes comes a new selection of mysteries to solve.

aficionados to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around 5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by Winter:

aficionados to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around 5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by Winter: