ChessBase 2014 Christmas Puzzles

For the fifteenth anniversary of our apparently well-loved Christmas puzzles

we have decided to go back in time and pick some of the best or most popular

puzzles for you. Remember there are GM readers (and one of our regular authors)

out there who were not born when we started the series. For older readers

the cherries we will pick out of the original section will hopefully bring

on nostalgic memories; and the younger ones will learn for the first time

what we have been up to over the years.

(One top GM, who is approaching 2800, wrote us: "Terrible puzzles

on the ChessBase page. Especially the first one. It keeps bothering my brain

during my holidays. It took me couple days to figure out it's must be Black

who is mating, but I am still struggling to see how.")

And of course we will start the new year with our traditional Christmas

puzzle contest. On the first of January 2015 you will get some problems

to solve, with the chance of winning interesting prizes. In the meantime

here are the final three sections for 2014. The page will be updated from

December 29–31.

December 29, 2014: My

favourite studies

I

was introduced to chess studies by one person, a world champion, and one

book. It was over thirty years ago, in 1981, when a young Finn named Mika

Korhonen came to stay for a week in my home. Mika was part of the Finnish

problem solving team that had won the world championship in the helpmate

section. He had written one of the world's first problem solving programs,

Mika's Mate, for the Apple II computer.

I

was introduced to chess studies by one person, a world champion, and one

book. It was over thirty years ago, in 1981, when a young Finn named Mika

Korhonen came to stay for a week in my home. Mika was part of the Finnish

problem solving team that had won the world championship in the helpmate

section. He had written one of the world's first problem solving programs,

Mika's Mate, for the Apple II computer.

Mika was also an endgame specialist, and he brought with him a book that

we read, virtually from cover to cover, while he was there. It was John

Roycroft's The Chess Endgame Study. Originally the book had appeared

around 1972 and had been called Test Tube Chess, but Mika had the

latest edition with the new title.

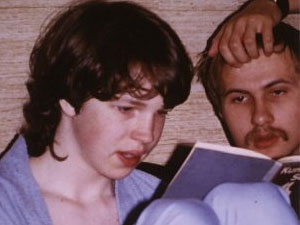

There was another guest staying with us at the time. It was a young boy

from England, fifteen years old, tall and lanky, with feminine features

and a giant Elo. It was Nigel Short, still an IM and playing in a Hamburg

Grandmaster Tournament. Every morning, still in his pyjamas, every evening

and on his free days he joined in the fun and solved studies with us. Naturally

he was much better at it, so Mika had to pull out helpmates and other weird

stuff to put the lad in his place.

I still own Roycroft's book, which Mika left behind, unable to bear the

traumatic parting scenes that would have inevitably followed. It is well-thumbed,

with dog's ears and little slips of paper in it, and pencilled notes on

the side of hundreds of positions. These include solving times for Nigel

and other top GMs who visited me, as well as for early chess computers.

Big heavy "X"s mark my favourite studies. My taste has not changed

substantially over the years.

15-year-old Nigel Short and Mika Korhonen solving

puzzles

M. Klyatskin, Schachmat 1924

White to play and win

Let us start solving this position. 1.Rxa8 is naturally the first move

we check, but 1...Nxa8 2.Kxa7 Kxc6 3.Kxa8 Kb5 is an obvious draw. So we

check 2.Kb7 Nc7 3.a6 Nxa6, which also only draws.

So let's try 1.axb6 Rxb8 2.bxa7, but again 2...Re8 (for instance) 3.Kb7

Re7+ is a draw (4.Kb8 Rxa7).

What else? 1.c7 looks promising, since Black can't take the rook. But after

1...Kxc7 2.Rxa8 Nxa8 we are once again left with a draw.

So how on earth is White to win? Well, you can enter the study in Fritz

or Komodo and find out in a millisecond. Or you can enjoy the exquisite

pleasure we experienced at the time, setting up the position on a chessboard

and working it out all on our own. They were good days.

J. Gunst, Das illustrierte Blatt, 1922

White to play and win

Now this is a really simple position, isn't it? It is immediately clear

that White must capture the black pawns without losing either of his pieces.

But these are being acutely threatened by the black king.

We should be able to work out the solution by brute force. Let's start

by eliminating the obviously bad tries: any king or knight moves drop the

bishop and the game is immediately drawn. This is an enormous help, because

we now know that the first move must be with the bishop.

So let's start with 1.Bxd7. Unfortunately 1...Kc7 results in one of the

white pieces being captured and a draw. This means we are left with only

two candidate moves. We try 1.Bb7, and are again confronted with 1...Kc7.

Black again picks up one of the white pieces and draws. So obviously the

correct move is 1.Ba6. But hang on, after 1...Kc7 where does the knight

go? Once again it is captured and Black has secured the draw.

We have run out of moves, the problem doesn't appear to have a solution.

Maybe there is an error in the diagram? This is a very unpleasant possibility

that come up more often than you'd expect in chess magazines. One spends

hours working on a study and in the next issue the editor writes "we

apologize for an error in the diagram, there was a white pawn missing on

b5" or something like that. But rest assured, the above diagram is

correct, the position is wKd5, Nb8, Bc8, bKd8, Pa7, Pd7, six pieces on the

board, three of each colour.

So how in the world does White win? Well, that is your task for today –

or one of them. Out with the chessboard and six pieces, and a hot coffee,

cold beer or nice glass of wine, whatever is your thing. Just leave the

computer out of it.

– Part two of My Favourite Studies will follow

tomorrow –

Please do not post any solutions in the discussion section below and spoil

the fun for everyone else. Nobody will admire you for it, and some will

be extremely annoyed. Just keep it all to yourself.

I

was introduced to chess studies by one person, a world champion, and one

book. It was over thirty years ago, in 1981, when a young Finn named Mika

Korhonen came to stay for a week in my home. Mika was part of the Finnish

problem solving team that had won the world championship in the helpmate

section. He had written one of the world's first problem solving programs,

Mika's Mate, for the Apple II computer.

I

was introduced to chess studies by one person, a world champion, and one

book. It was over thirty years ago, in 1981, when a young Finn named Mika

Korhonen came to stay for a week in my home. Mika was part of the Finnish

problem solving team that had won the world championship in the helpmate

section. He had written one of the world's first problem solving programs,

Mika's Mate, for the Apple II computer.