Match of the Century in Reykjavik

From Frank Brady's book Bobby Fischer, Batsford 1974

As we reported yesterday the World Championship Challenger, grandmaster Bobby Fischer from USA, made an extraordinary move in the first game against Boris Spassky: instead of going for a safe draw – which would have been his first with the black pieces against the Russian – Fischer captured a "poisoned" pawn, a move that left cost him a bishop for two pawns and put him in grave danger of losing the game. US chess columnist Robert Byrne said: "Fischer is playing desperately for a draw." GM Larry Evans felt Fischer had drawing chances, "perhaps." Yugoslav chess GM Svetozar Gligoric thought Fischer's chances were "slim." But Russian delegation chief Nikolai Krogius said it was "...probably a draw," which left Fischer fans with reasons to hope. We hand over once again to Frank Brady, who watched the second day of the game unfold.

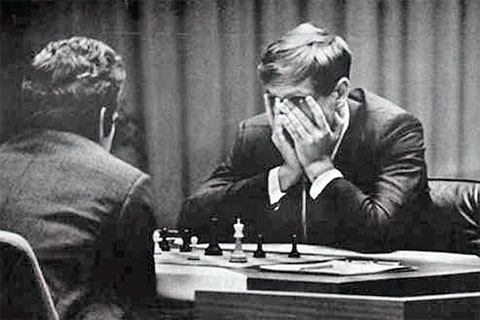

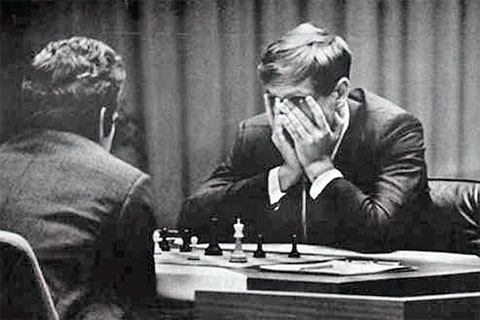

Fischer analyzed the position through the night and appeared for the adjournment, looking tired and worried, just two minutes before Schmid opened the sealed-move envelope. Schmid made Spassky's move for him on the board, showed Fischer the score sheet so he could check that the correct move had been made, and activated his clock. Fischer responded within seconds, and a few moves were exchanged.

Right at the start of game one Fischer glares at the TV camera...

... gets up from his chair and walks over to arbiter Lothar Schmid to protest...

Stills from the Liz Garbus documentary "Die Legende Bobby Fischer" in Arte TV

Fischer then pointed to the camera aperture that he had complained about the day before, and quickly left the stage with his clock running. Backstage, he vehemently complained about the camera, and said he wanted it dismantled before he continued play. ICF officials quickly conferred with Chester Fox, owner of the film and television rights, who agreed to remove the camera. All of this took time, and Fischer's clock continued running while the dismantling went on.

Schmid finally went back to Fischer's dressing room and knocked at his door. "Bobby, the cameras have been removed," he called. "You're a liar," Fischer snapped. Schmid, furious, went back to the stage. Eventually, Saemunder Paalsson, the policeman who had been acting as Fischer's unofficial bodyguard, assured Bobby that he had personally checked that the camera was no longer in operation. When Fischer returned to the stage, thirty-five minutes had elapsed on his clock.

Fischer began fighting for a draw, but Spassky's moves were a study in precision and his position became stronger as they played on. Eventually, it became clear that Spassky could queen a Pawn. Instead of making his fifty-sixth move, Fischer stopped the clock and offered his band in resignation. He wasn't smiling. Spassky did not look him in the eye as they shook, but continued to study the position. Fischer signed his score sheet, made a helpless gesture as if to say "What am I supposed to do now?" and left the stage. It is not difficult to guess his emotional state.

Fischer resigns the first game against Boris Spassky after 60 moves

<img data-cke-saved-src="http://en.chessbase.com/portals/4/files/news/2012/brady03b.jpg" src="http://en.chessbase.com/portals/4/files/news/2012/brady03b.jpg" width="150" "="" height="218" border="1" class="dropshadow" style="float: right; margin-left: 10px; margin-bottom: 5px; width=" 250="">Though there have been a number of world's championship matches where the loser of the first game went on to win the match, including Spassky-Petrosian, 1969 (and Euwe-Alekhine, 1935, Petrosian-Botvinnik, 1963 and Stenitz-Tchigorin, 1892), there is no question that Fischer considered the loss of the first game almost tantamount to losing the match itself. Not only had he lost, but he had been unable to prove to himself and to the public that he could win a single game from Spassky. Their lifetime score stood at four wins for Spassky, two draws, and no wins for Fischer. Bobby undoubtedly descended into a rage of self-doubt and uncertainty. Since an inner-directed revenge was unthinkable, the cameras were to blame for his loss, not Spassky's superior – or his own inferior – play.

The above text was taken from the Batsford edition of Frank Brady's 1974 book, of which we possess (and treasure) a rare copy. There appears to be one available at AbeBooks, but probably our readers will find more.

| Replay and check the LiveBook here |

Please, wait...

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 d5 4.Nc3 Bb4 5.e3 0-0 6.Bd3 c5 7.0-0 Nc6 8.a3 Ba5 9.Ne2 dxc4 10.Bxc4 Bb6 11.dxc5 Qxd1 12.Rxd1 Bxc5 13.b4 Be7 14.Bb2 Bd7 15.Rac1 Rfd8 16.Ned4 Nxd4 17.Nxd4 Ba4 18.Bb3 Bxb3 19.Nxb3 Rxd1+ 20.Rxd1 Rc8 21.Kf1 Kf8 22.Ke2 Ne4 23.Rc1 Rxc1 24.Bxc1 f6 25.Na5 Nd6 26.Kd3 Bd8 27.Nc4 Bc7 28.Nxd6 Bxd6 29.b5 Bxh2 30.g3 h5 31.Ke2 h4 32.Kf3 Ke7 33.Kg2 hxg3 34.fxg3 Bxg3 35.Kxg3 Kd6 36.a4 Kd5 37.Ba3 Ke4 38.Bc5! a6 39.b6 f5 40.Kh4 f4 41.exf4 Kxf4 42.Kh5 Kf5 43.Be3 Ke4 43...g6+ 44.Kh6 Kf6 45.Bd2 Kf5 46.Bg5 e5 47.Bd2 Kf6 48.Be3 Kf5 49.Bg5+- 44.Bf2 44.Bc1+- Kf5 44...Kd3? 45.Kg6 Kc2 46.Kxg7! Kxc1 47.Kf6+- 44...Kd5 45.Kg6 Kc5 46.Be3+ Kb4 47.Kf7 47.Kxg7? Kxa4 48.Kf6 Kb5 49.Kxe6 Kc6= 47...Kxa4 48.Kxe6 Kb5 49.Kd7 a5 50.Kc7 Ka6 51.Bd4 g5 52.Bf6 g4 53.Be5 a4 54.Bd6+- 45.Bg5 e5 46.Bc1 e4 47.Be3 44...Kf5 45.Bh4 e5 46.Bg5 e4 47.Be3 Kf6 48.Kg4 Ke5 49.Kg5 Kd5 50.Kf5 a5 50...Kc4 51.Kxe4 Kb4 52.Kd5 Kxa4 53.Kd6 51.Bf2 g5 52.Kxg5 Kc4 53.Kf5 Kb4 54.Kxe4 Kxa4 55.Kd5 Kb5 56.Kd6 56.Kd6 a4 57.Kc7 Ka6 58.Bc5 Kb5 59.Bf8 Ka6 60.Be7+- 1–0 - Start an analysis engine:

- Try maximizing the board:

- Use the four cursor keys to replay the game. Make moves to analyse yourself.

- Press Ctrl-B to rotate the board.

- Drag the split bars between window panes.

- Download&Clip PGN/GIF/FEN/QR Codes. Share the game.

- Games viewed here will automatically be stored in your cloud clipboard (if you are logged in). Use the cloud clipboard also in ChessBase.

- Create an account to access the games cloud.

| Spassky,B | 2660 | Fischer,R | 2785 | 1–0 | 1972 | E56 | World Championship 28th | 1 |

Please, wait...

Was 29...Bxh2 an amateur-level blunder?

There has been much speculation on what is certainly one of the most famous moves of all time, the 29...Bxh2 cannonball that ultimately cost Fischer the first game and almost the entire match. What led Fischer to the kamikaze action and

| Replay and check the LiveBook here |

Please, wait...

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 d5 4.Nc3 Bb4 5.e3 0-0 6.Bd3 c5 7.0-0 Nc6 8.a3 Ba5 9.Ne2 dxc4 10.Bxc4 Bb6 11.dxc5 Qxd1 12.Rxd1 Bxc5 13.b4 Be7 14.Bb2 Bd7 15.Rac1 Rfd8 16.Ned4 Nxd4 17.Nxd4 Ba4 18.Bb3 Bxb3 19.Nxb3 Rxd1+ 20.Rxd1 Rc8 21.Kf1 Kf8 22.Ke2 Ne4 23.Rc1 Rxc1 24.Bxc1 f6 25.Na5 Nd6 26.Kd3 Bd8 27.Nc4 Bc7 28.Nxd6 Bxd6 29.b5 Bxh2 30.g3 h5 31.Ke2 h4 32.Kf3 Ke7 32...h3 33.Kg4 Bg1 34.Kxh3 Bxf2 35.Bd2 33.Kg2 hxg3 34.fxg3 Bxg3 35.Kxg3 Kd6 36.a4 Kd5 37.Ba3 Ke4 38.Bc5 a6 39.b6 f5 40.Kh4 f4 41.exf4 Kxf4 42.Kh5 Kf5 43.Be3 Ke4 44.Bf2 Kf5 45.Bh4 e5 46.Bg5 e4 47.Be3 Kf6 48.Kg4 Ke5 49.Kg5 Kd5 50.Kf5 a5 51.Bf2 g5 52.Kxg5 Kc4 53.Kf5 Kb4 54.Kxe4 Kxa4 55.Kd5 Kb5 56.Kd6 1–0 - Start an analysis engine:

- Try maximizing the board:

- Use the four cursor keys to replay the game. Make moves to analyse yourself.

- Press Ctrl-B to rotate the board.

- Drag the split bars between window panes.

- Download&Clip PGN/GIF/FEN/QR Codes. Share the game.

- Games viewed here will automatically be stored in your cloud clipboard (if you are logged in). Use the cloud clipboard also in ChessBase.

- Create an account to access the games cloud.

| Spassky,B | 2660 | Fischer,R | 2785 | 1–0 | 1972 | E56 | World Championship 28th | 1 |

Please, wait...

Many modern chess engines show interest in playing 29...Bxh2, at least in the first seconds of their computations. And they do it not because they are going to try to save the bishop – simply sacrifice it for two pawns and hold the draw.

It would be interesting if we could, today, 40 years after the historic move was made, get some final analysis by the most powerful computers in the world. How about a communal Let's Check analysis session, where everyone looks at lines that have not yet been analysed to a great depth. Our suspicion: it will turn out that Fischer's move was playable, and that he could have and would have held the draw – if his situation in Reykjavik had not been so full of anguish and frustration.

Copyright Brady/ChessBase

Links

|

Match of the Century begins in Reykjavik

11.07.2012 – That could have been the headline of our newspage, exactly forty years ago this afternoon, when after some harrowing manoeuvring the US Challenger Bobby Fischer sat down to the first game of the World Championship match against Boris Spassky in Iceland. It was a very tense encounter and has been beautifully recreated by Frank Brady, who was an eye-witness at the scene. |

|

Brady – Bobby Fischer's Game of the Century

29.05.2011 – We recently published a review by Sean Marsh on Frank Brady's new biography of Bobby Fischer. In the meantime we have received the handsome volume from the author and are actually reading it – with immense pleasure. To give you an impression of the quality of this book we bring you a short excerpt of a story you know. Read how wonderfully Dr Brady weaves the well-known tale. |

|

Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall...

25.04.2011 – ... from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness. That's the full title of a fascinating book we are currently reading, one which was written by Dr Frank Brady, who knew Fischer from his early youth onwards. It is going to take us some time to go through all 402 pages, so for now we bring you, courtesy of the English magazine CHESS, an in-depth review by Sean Marsh. |