.jpeg)

.jpeg)

After his tumultuous arrival in Reykjavik, the preparations for the Match of the Century in Laugardalshöllin, and the disaster he suffered in game one, Challenger Bobby Fischer was on the verge of abandoning the entire event and returning home.

Fischer complained to match arbiter Lothar Schmid that the camera poking through a hole in the blue-and-white FIDE sign located at the back of the stage in game one had been disturbing him.

For game two he demanded that all television cameras be dismantled, and a number of front row spectator seats be removed.

Game two was scheduled for Thursday, July 13. The camera towers were dismantled, and the cameras themselves moved into two small alcoves, above the stage, that housed the air-conditioning. From there they could film the action through four-inch holes. Match arbiter Lothar Schmid turned up in the playing hall at 2:40 p.m. and examined the setup. "If Bobby will object to this," he said, "I will rule against him," he said.

At 4:30 Fischer's manager Fred Cramer called from the playing hall and told Bobby: "The towers are out, and also the camera backstage. They've found a great new place for the cameras – completely invisible and inaudible!" But Fischer was adamant: "I want all cameras out!" He refused to proceed to the hall. At five p.m., the starting time of the game, Schmid walked onto the stage and started Fischer's clock. The challenger had 60 minutes to make his first move. If he didn't he would forfeit the game.

Icelandic Chess Federation President Gudmundur Thorarinsson (above) now suggested that Fischer should play the second game under protest – to which Bobby simply said: "What does he think I am, a fool? Tell Thorarinsson if they forfeit me that's it: I'm taking the next plane back home." Grandmaster Fridrik Olafsson intervened and at 5:47 p.m. and, after speaking with Fischer, called Schmid to tell him: "Bobby will play, but you must ask Spassky if he will agree to restart the clocks." Schmid replied: "I cannot. Bobby has twelve minutes to make his move." At 6 p.m. Schmid stepped up to the playing table and stopped the clock. "Mr Fischer did not appear in the playing hall," he announced. "According to rule five of the Amsterdam Agreement he loses the game by forfeit."

In the hallways the display showed: Fischer has forfeited the second game – the score was now 0:2

What then transpired is vividly described by Prof. Christian Hesse in A great moment in chess. It is part three of a 2008 article series you might be interested to read. Links are given at the end of this article:

Bobby Fischer formally protested the forfeit with a long letter to Lothar Schmid delivered by him in person in the early hours of July 14 to Schmid's hotel room. Another of Fischer's lawyers, Andrew Davis, arrived a few hours later from the US to convince members of the Match Committee to overrule Schmid's forfeit decision. The Committee met at 10 a.m. the same day. It upheld the referee's ruling.

After this ruling, Fischer asked Fred Cramer, his chief assistant in Reykjavik, to prepare for him to leave Iceland. Shortly afterwards, he holds a reservation for the 3:15 p.m. flight to New York on July 17. Fischer told Cramer: “I want you to pick up those tickets tonight and bring them up here to me. Then I want you to figure out some plan to sneak me out to the plane. They might try to stop me, you know. It has got to be secret.”

While all this is going on, Henry Kissinger is in San Clemente, California, involved in several rounds of extensive talks with the Soviet ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin during a US-Soviet summit. At some stage during the day he found the time to place a phone call to Reykjavik 22322, the number to reach Fischer. In addition, many telegrams arrived for Fischer urging him to play on.

Fischer is known to have made the decision to continue almost at the last minute, sometime early afternoon on Sunday, July 16, the day scheduled for game three. He had earlier asked Cramer to change his reservation to the last plane leaving Reykjavik that day. Around 3 p.m. Cramer knocked on Fischer's door to pick him up for the flight. His second William Lombardy opened the door, Paul Marshall also being in the room, the telegrams being scattered all over.

Fischer: “That two-game edge is gonna make it hard. But I can still do it, you know.”

Marshall: “I know you can, Bobby.”

Fischer: “All right. But you have to get me in that back room.”Marshall acted by phoning Schmid, telling him that Fischer had agreed to play if game 3 was held in a small, thirty-by-sixty foot separate room at the back of the stage without cameras, out of view from the spectators in the main hall. It was normally used for ping-pong. The Amsterdam Agreement, signed by both players, stated that a game could be moved to this room if there was a disturbance in the main hall.

Brad Darrach reports that at this stage Marshall said: "I've got it!" Striding to the nearest wall he jerked a fire ax out of its socket and brandished it. "You need a disturbance? I'll give you a disturbance! I'm going down to the stage right now and but up that chess table! With the table wrecked you couldn't play in the hall, you'd have to play up here. How many days in jail for destroying private property? One day? Hell, it's worth it!" Schmid tried to laugh. "That will not be necessary," he said. "I-I will call Mr Spassky."

Schmid considered himself to be acting beyond his authority if he simply moved game 3 there. He had to get Spassky's approval. He called the Champion immediately. Spassky said: “Pozhaluista” (That's o.k. with me.) He took the decision without conferring with his team. The team members found out only when they took their seats in the main auditorium. Spassky had felt he had to give Fischer something in return for the free point.

Not much later, a few minutes before 5 p.m., Lothar Schmid was in the ping-pong room. It did not contain much more than a chrome and black chair for Fischer and a simple armchair for Spassky as well as a playing table.

Schmid opened a window. The sound of children playing outside could be heard. Spassky arrived shortly afterwards and looked around for Fischer. But he was not there. Spassky sat down at the chessboard. Then Fischer arrived. And his eyes fell immediately on a closed-circuit television camera that had been installed in the ceiling to broadcast the game to the large audience in the main hall, the journalists in the press room and the commentators. It had been wrapped in blankets. The spectators had paid five dollars each, and some of them later complained that there was only a TV-screen instead of the real thing.

“No cameras!” Fischer roared. He paced the room back and forth, turning switches on the wall on and off. Schmid asked him to stop since Spassky was being disturbed. “Shut up, Lothar!” Fischer yelled back at Schmid.

Spassky turned white and stood up. Schmid later recalled:”When Bobby yelled at me, Boris became upset and said “If you do not stop the quarrel, I will go back to the playing hall and demand to play there.” Spassky had reached the door already. Schmid was panic-stricken. He pleaded with Spassky: ”Boris, you promised.” Spassky shrugged his shoulders. Schmid turned to Fischer: ”Bobby, please be kind.” Schmid recollects:”I felt there was only one chance to get them together. They were two grown-up boys, and I was the older one. I took them both and pressed them by the shoulders down into their chairs and I said: ”Play chess now!” And almost automatically, Spassky made the first move, 1.d4, the same he had played in game 1.”

Fischer initially still contemplated whether to stay or whether to leave. But then at 5:09 he took his king-side knight and put it to f6. His desire to play chess had gained the upper hand. The world championship match had been saved. There was tremendous applause from the spectators in the main hall. The players, though, could not hear it.

Game three was covered by a single camera which Fischer made sure did not move

In the hallway the audience could watch the grainy image on close circuit TV, with a grandmaster analysing on demo boards

The events just described constitute the psychologically decisive moment of the entire match. In terms of score, Fischer was two full points behind. In his entire life, he had never beaten Spassky. He had blundered away a drawn position in Game 1. And now he had the black pieces. When he entered that little back-stage room, his face was grey-white, almost greenish. But he played that third game for a win, virtually from move one onward, introducing an entirely new conception early on. He played that game as if his entire life depended on it. And he won it with very intricate play. It changed the psychology of both players. Fischer had proven to himself that he could beat Spassky. And with black.

Boris Spassky with Christian Hesse in Bonn 2007

On January 21, 2007, Boris Spassky came to Bonn to give a simultaneous display. Before the event, he, Lothar Schmid and Dr. Helmut Pfleger talked in front of a large audience about the events and the psychology of the Reykjavik match. Afterwards a small group of people, including Schmid and the author, took Spassky to dinner at a local restaurant. I asked him specifically about the situation before the start of Game 3 in Reykjavik. He mentioned that when Fischer started to quarrel with Schmid and told him to shut up, he should have stood up and said: “Gentlemen, I will not play under these circumstances. I am leaving. You can forfeit me but I am not playing." Fischer would have been in a very difficult psychological position. "But I missed this opportunity.”

This is what the "ping-pong room" in which game three was played looks like today (2017)

Since it is used for activities like ballet it has mirrors on two of the walls

And this is how the recent movie "Pawn Sacrifice" reconstructed the game three room

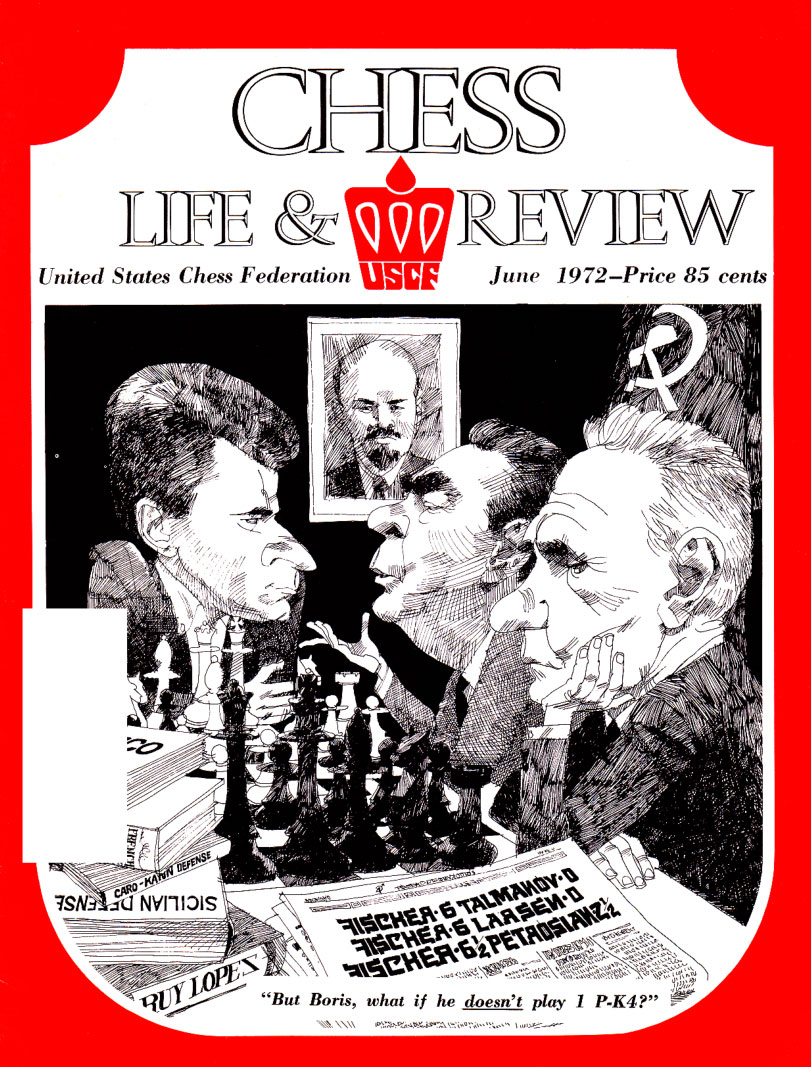

The June 1972 cover of Chess Life & Review (click to enlarge) had a cartoon by Bob Walker, of Boris Spassky consulting with Leonid Brezhnev and Alexei Kosygin before the match.

In the September 1972 issue of Chess Life & Review GM Robert Byrne, who was in Reykjavik, wrote: "Although he had little sleep, [Fischer] shifted to the belligerent Benoni as Black in the third game and ran Spassky off the board. After Bobby's radically powerful 11 . . . N-R4, he shortly began wrapping up one of the most one-sided victories in a championship match. It was the first defeat in his lifetime over Boris, who had beaten him four times previously over the board, including the match opener. The score was now 2-1 for Spassky."

[Event "Reykjavik World Championship"] [Site "Reykjavik"] [Date "1972.07.16"] [Round "3"] [White "Spassky, Boris Vasilievich"] [Black "Fischer, Robert James"] [Result "0-1"] [ECO "A77"] [WhiteElo "2660"] [BlackElo "2785"] [Annotator "Sagar Shah"] [PlyCount "82"] [EventDate "1972.07.11"] [EventType "match"] [EventRounds "21"] [EventCountry "ISL"] [SourceTitle "MainBase"] [Source "ChessBase"] [SourceDate "1999.07.01"] {This was perhaps the most important game of the match. Fischer was trailing 2-0. He had never beaten Spassky in a competitive game before this encounter. Here, he not only beat Spassky, but did so in great, great style.} 1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 c5 $5 {When you are trailing the match by two points, what should be done? Many players would like to make a quick draw and get back into the groove. Not Fischer. He wanted to win at all costs, and for that he was also ready to employ the Benoni.} 4. d5 exd5 5. cxd5 d6 6. Nc3 g6 7. Nd2 $5 { This is one of the main responses against the Benoni. It was a favourite of Tigran Petrosian. White plays positionally, builds up a strong centre and through accurate prophylactic moves tries to take the fun out of Benoni.} Nbd7 8. e4 Bg7 9. Be2 O-O 10. O-O Re8 11. Qc2 {White has played the opening in Typical fashion. In fact Petrosian now loved to continue with a4, followed by Ra3. With this manoeuvre, the rook gets off the diagonal of the g7 bishop and also proves to be useful for defence on the third rank.} Nh5 $5 {What?!! Did Fischer overlook that his knight on h5 can be taken by the white bishop? Of course, not! This move, ...Nh5, just like ...Bxh2 in game one, shook the chess world. It turned out to be one of the most amazing pieces of home preparation ever seen at the World Championship level.} 12. Bxh5 {Taking this knight is, of course, the correct decision.} gxh5 {Black has this ugly doubled h-pawns. While optically this is a disaster, practically it is not so bad. Black gets to use the h-pawn as a battering ram into White's position. Also the g-file has opened up, which can be used for an attack, and most importantly, White had to give up his crucial bishop.} 13. Nc4 (13. a4 {with the idea of Ra3 and swinging the rook to the kingside was a worthy idea to consider.} Ne5 14. h3 f5 15. f4 Nf7 16. Nc4 b6 $132 {[%cal Gc8a6]}) 13... Ne5 14. Ne3 (14. Nxe5 Bxe5 15. Be3 {could have been the simple way to play the position. But I think Black should be fine after} f5 $5 $132) 14... Qh4 15. Bd2 Ng4 16. Nxg4 (16. h3 Nxe3 17. Bxe3 Kh8 $132 {Black already has excellent play.}) 16... hxg4 {Black has solved his doubled h-pawn issue. Now along with the excellent pawn strucutre, he also has the bishop pair.} 17. Bf4 Qf6 18. g3 Bd7 {Now everything is ready for queenside expansion.} 19. a4 b6 {Black goes slow. He realizes that ...a6 will be met with a5. Hence first begins with this move and then a6 followed by b5.} 20. Rfe1 a6 21. Re2 (21. e5 $2 dxe5 22. Ne4 Qg6 $17) 21... b5 22. Rae1 Qg6 23. b3 Re7 24. Qd3 Rb8 25. axb5 axb5 26. b4 $6 {Usually the move b4 is played to fix the b5 pawn and also gain the d4 square. But here the white knight is quite far from the d4 square and hence ...c4 is the right move.} c4 $17 { Along with all his trumps, Black now also has a protected passed pawn.} 27. Qd2 Rbe8 28. Re3 h5 (28... Bxc3 29. Qxc3 Rxe4 $17 {winning a pawn was the computer's way of playing the position. Fischer hits on this plan only after repeating the position for a few moves.}) 29. R3e2 Kh7 30. Re3 Kg8 31. R3e2 Bxc3 32. Qxc3 Rxe4 33. Rxe4 Rxe4 34. Rxe4 Qxe4 35. Bh6 Qg6 36. Bc1 Qb1 37. Kf1 (37. Kg2 Bf5 $19) 37... Bf5 38. Ke2 Qe4+ 39. Qe3 (39. Kf1 Qh1+ 40. Ke2 Bd3+ $19 ) 39... Qc2+ 40. Qd2 Qb3 41. Qd4 (41. Qe3 c3 $19) 41... Bd3+ {The b4 pawn also falls. This was the first time that Fischer scored a win over Spassky in a competitive game. What a morale boosting victory for the American! After this game he really started believing that he could beat Spassky and become the World Champion. This game will always be remembered for the move ....Nh5! Knights on the rim aren't always dim!} 0-1

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (1)

In the final week of June 1972 the chess world was in turmoil. The match between World Champion Boris Spassky and his challenger Bobby Fischer was scheduled to begin, in the Icelandic capital of Reykjavik, on July 1st. But there was no sign of Fischer. The opening ceremony took place without him, and the first game, scheduled for July 2nd, was postponed. Then finally, in the early hours of July 4th, Fischer arrived. Frederic Friedel narrates.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (2)

The legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer was staged in the Laugardalshöllin in Reykjavik. This is Iceland’s largest sporting arena, seating 5,500, but also the site for concerts – Led Zeppelin, Leonard Cohen and David Bowie all played there. 45 years after the Spassky-Fischer spectacle Frederic Friedel visited Laugardalshöllin and discovered some treasures there.

Bobby Fischer in Iceland – 45 years ago (3)

On July 11, 1992 the legendary Match of the Century between Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer finally began. Fischer arrived late, due to heavy traffic. To everybody's surprise he played a Nimzo instead of his normal Gruenfeld or King's Indian. The game developed along uninspired lines and most experts were predicting a draw. And then, on move twenty-nine, Fischer engaged in one of the most dangerous gambles of his career. "One move, and we hit every front page in the world!" said a blissful organiser.

A great moment in chess (Part 1)

A great moment in chess (Part 1)

11/27/2007 – It’s 7 minutes past 5 o’clock in the afternoon on July 17th, 1972. The place is a small backstage room of Laugardalsholl in Reykjavik, Iceland, the venue for the Fischer versus Spassky World Championship Match. It’s Game 3 of their titanic struggle which has been called the Match of the Century. Fischer, playing black, had just made his first move. Prof. Christian Hesse narrates.

A great moment in chess (Part 2)

1/15/2008 – Reykjavik, July 11, 1972. Of the 3000 spectators at the "Match of the Century" 500 have already left, since the position on the board has no winning chances for either side. But then Bobby Fischer plays 29...Bxh2. Gudmundur Thorarinsson, President of the Icelandic Chess Federation, says: "One move and we hit every front page everywhere in the world." Prof. Christian Hesse narrates.

A great moment in chess (Part 3)

4/17/2008 – July 13, 1972. Reykjavik, Iceland. Challenger Bobby Fischer attributes the loss, two days earlier, of the first game of his match against World Champion Boris Spassky to disturbances by the TV cameras in the playing hall. He wants them removed. But there is a deal with an American producer that cannot be broken. Will Fischer appear for the game or default? Prof. Christian Hesse narrates.

A great moment in chess (Part 4)

9/28/2008 – July 15, 1972. Reykjavik, Iceland. After threatening to abandon the World Championship match and leave Iceland, Challenger Bobby Fischer appears for game three, in a back room of the theatre. There he discovers a closed-circuit television camera for the audience in the main hall. “No cameras!” he roars. Prof. Christian Hesse recounts the harrowing events surrounding the match.