Almost exactly nine years ago we formally urged FIDE to take steps to combat a growing danger faced by chess. After a verbal discussion with FIDE officials on October 17, 2005 (at the airport of San Luis, Argentina). Frederic Friedel proposed simple measures that would make it harder for players to cheat during a top-level event (like delaying the live broadcast of moves over the Internet by fifteen minutes). He was asked by President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov to submit a proposal to the FIDE Presidential Board. This he did, on at least three separate occasions, over the years. Now at least the most rudimentary (and obvious) points have been formally included in section 11.3 the Laws of Chess. This is encouraging – but certainly not the end of the matter.

For the historical record we bring you the final part of Friedel's 2000 paper on Cheating in Chess. It summarizes the problems the game is facing – problems that have, if anything, become more acute with the passing of time and advances in technology. We have added a few contemporary notes where it seemed appropriate.

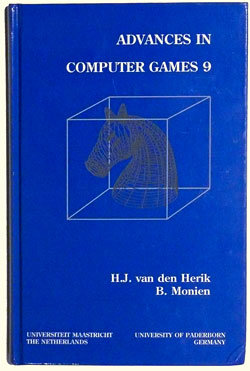

Advances in Computer Games 9", edited by Professors H. J. van den Herik, University Maastricht, and B. Monien, University of Paderborn. It was published by the Universiteit Maastricht in 2001. The paper on Cheating was written and submitted by the author in 2000.

Advances in Computer Games 9", edited by Professors H. J. van den Herik, University Maastricht, and B. Monien, University of Paderborn. It was published by the Universiteit Maastricht in 2001. The paper on Cheating was written and submitted by the author in 2000.

Abstract

Nowadays, players at all levels of chess can profit from computer assistance during a game of chess. This is a new development and a serious problem for the game. This contribution lists the main forms of cheating and provides some occurrences from practice. The most prevailing one (Allwermann at the Böblinger Open) is placed in a historical context by describing previously noticed cases of cheating.

Finally, the problem of cheating is addressed at the highest level of play. What are the possibilities and how can we prevent cheating at this level? Since there is no clear solution, the problem of cheating remains on the list of issues to be addressed very seriously in the near future.

Part 5 (final): The problem

The fact that players at all levels of chess can profit from computer assistance during a game is a new development and a serious problem for chess. Ironically the World Chess Federation FIDE has chosen this moment in time to attack another far less critical matter and wants to introduce doping controls in chess. At the Linares tournament in March 2000 top players were asked for their opinion on the FIDE initiative. Vladimir Kramnik and Garry Kasparov both said it was fairly silly (Kasparov: “What are they going to check for, coffein in your blood?”). Especially Kramnik was very outspoken. “Instead of a doping control, which is meaningless in chess, they should have airport-style security systems at all major tournaments to make sure nobody is getting help from computers during the game. That is a much greater danger.”

Most top grandmasters understand all too well how computers can affect the outcome of a game. In contrast to an amateur playing 600 points above his true strength, for whom the computer must dictate practically every move of the game, a strong grandmasters requires only occasional assistance to improve his performance dramatically. There are usually a few critical positions in which a player must decide whether a promising plan can work, or whether it is tactically flawed. One can only speculate how many brilliancies have not been executed because the player just wasn’t able to check all the lines in the time available (or because no human is able to do so in very complex positions).

Naturally the temptation would be great to have computer assistance in these situations. The problem is made more acute by the fact that only very little information needs to be passed, and on very few occasions. If we return to the example of the Las Palmas game given in part four, Kasparov’s second knew what he was looking at and actually uncovered the solution before the move was played. All that Kasparov needed was one bit of information: “Yes”. He didn’t need to get the message “20.g4! wins” but simply “There is a win” or even, in this specific case “The move we know you are looking at works!” That would have been enough to decide the game.

The problem is more serious the higher you go up the Elo scale. Not only do the players need progressively less information, they also stand to gain progressively more from cheating with the computer. Whereas in a big national open like Böblingen players stand to gain less than a thousand dollars, the sum increases to tens of thousands in top international tournaments, or even up to a million dollars in the case of a World Championship (the difference between winning and losing – and not including the monetary benefits derived from winning the title). Cheating with the computer has, to the best of my knowledge, thus far not been attempted at top levels in chess. But the players are all well aware of the fact that there are bound to be attempts to do so in the future. It should be noted that cheating at higher levels can probably only occur with the help of computers. Normally no human is able to reliably assist a top grandmaster who is immersed in a game and understands it better than any onlookers.

No clear solution

When the Allwermann affair surfaced, Garry Kasparov and a number of other top players turned to us for advice on how to counter cheating in chess. The assumption was that since ChessBase makes the software that would be potentially used for clandestine computer assistance, it is we who would know how to counter such attempts. This was unfortunately not the case – there was no special expertise in our company with regard to electronic intelligence and counter-intelligence techniques.

In the months following the tournament, however, I was able to gather a lot of information on the subject. The main source was, of course, the Internet, where there is a profusion of sites explaining the technology at every level of detail (not to mention retailers offering to sell you every form of legal and illegal devices). I also discussed with Ken Thompson the kind of information that needs to be passed on and how this would be best generated by an assistant working with a fast tactical chess program like Fritz. Finally I got some invaluable information from Mark Lefler, chess programmer and US government employee who is an expert on security at US embassies abroad. Apart from describing advanced electronic methods Mark opened a whole new can of worms by describing to me all the non-electronic ways in which information can be passed on – especially in the miniscule amounts needed for cheating in chess.

|

In the meantime I have recruited another expert, Dr. Hartmut Schönbohm, an avid chess player and very active in the Playchess engine room. By profession he is an electrical engineer and software expert. He is also a stage magician who constantly attempts to fool me with conjuring tricks. I took Hartmut to chess tournaments, including some with top players. He was appalled at the lack of any real anti-cheating measures. His final expert report concluded with a very poignant sentence: "Pity! It was such a wonderful game." |

This brings us to a general problem I have in writing this article. If I were to now present a detailed account of all our findings it would be akin to writing a general instruction manual for cheating in chess. This is not my intention. On the other hand one must note that a lay person like myself can become a relative expert on the subject in a short period. It is frightening to think what a real specialist with criminal intent and a substantial budget could come up with in the same time.

|

Some time ago a chess magazine picked up the subject, enrolling real experts to describe the methods and possibilities of cheating in exquisite detail. Internet and shop addresses were given, telling readers where the required spy equipment was available, including prices and order forms. DIY instructions were also provided, e.g. on how to attach devices to your body and how to use them to transmit information to the outside world. All of this was ostensibly to draw attention to a very serious problem chess is facing. But in practice it was a comprehensive primer on how to take up cheating yourself. We thought that was, to say the least, counterproductive.

And no, we will not name the publication or the issue in which the article appeared. |

In this article and at the current time I have decided to be guarded in what I say and omit many of the details that would be of interest mainly to those actually interested in cheating. I will only draw attention in general terms to some of the problems faced by the counter-intelligence side of the equation. These are quite substantial.

1. It would seem to be a general rule that the cost of installing an electronic cheating mechanism is far lower that the cost of the equipment and infrastructure required to detect it. The factor appears to be about ten to one. You can start cheating in chess on a budget of around $100, and it would cost a tournament director around $1000 to reliably prevent this method of cheating from being used. If the perpetrator spends $1000 in electronic equipment then the other side must invest around $10,000 in order to thwart the attempt.

2. Airport-style detectors as envisioned by Kramnik will not pick up some of the electronic equipment that could be used to receive information during a chess game. There are currently devices on the market that use a very small amount of metal – in fact they have been specifically designed to elude detection by the usual methods. Apart from that there are ways in which a player could pass through a security detector without the receiver and obtain this later on during the game. This is standard espionage procedure. A whole set of additional measures, many extremely restrictive, need to be implemented to prevent this from happening.

3. Electronic receivers can be very cleverly concealed in many different parts of the body, and detecting them would require unacceptably intrusive searches. Remember that the signal does not have to be acoustic or verbal – you can easily transmit chess moves or yes/no information using a buzz, click, vibration or pulse. It is very difficult to detect a receiver that is may be smaller than some of the dental appendages the user is wearing – or may in fact be part of such appendages. Certainly this cannot be achieved using a standard airport metal detector.

4. The detection of the signal used to cheat is a similarly daunting task. It is important to remember that at the higher levels of chess we are dealing with just a few very short bursts of information, occurring within a five to seven-hour period. The transfer can take place at one of many different frequencies, and the signal may be more or less defused. Detecting the receiving device itself by its tell-tale electronic emissions is possible, but exceedingly difficult, especially if the perpetrator is using modern spy equipment that is designed to avoid exactly such detection.

5. It has been suggested that future matches must be held in Faraday cages (i.e. that the playing site would be shielded from all radio signals passing in or out by wire mesh covering the walls, floor and ceiling). There are a number of problems here as well. It may be feasible to put two players into an electronically shielded room, but how do you do this for an entire tournament with many players on different boards? Even with a two-player match special arrangements would have to be made for the participants leaving the table for refreshments, exercise or other human needs. If a player may step out of the electronically shielded area whenever he pleases then there is hardly any point in making it secure in the first place.

6. Another unfortunate aspect is that the information required for cheating at a higher level of chess can be transmitted in a variety of non-electronic ways. A well-known example is Victor Korchnoi’s complaint during the World Championship match in 1978 in Bagio City regarding yoghurt that was brought to his opponent Karpov during the game. Korchnoi feared that there might be messages encoded in the flavour of yoghurt being served – e.g. strawberry for a queenside attack, peach for the king-side. It is true that the simply placing of refreshments – yoghurt, mineral water, a cup of coffee – allows one to pass on a wealth of information, encoded in the choice of refreshment and how it is actually served, e.g. the position of the spoon, where the glass is placed, etc.

7. Conventional visual methods of communication are already quite well-known, and for many years in World Championship matches there have been arrangements to restrict the visual contact between the players and their seconds. But of course it is quite easy to use an unknown person to transmit signals. If the players can see any people in the audience then there are countless methods in which someone can pass him game-decisive information. If it is done in a fairly sophisticated way a single glance is enough to read the message. In fact the player doesn’t even have to look directly at the messenger, so that detection becomes even more difficult. The only reliable way to prevent this is to make sure that the players have absolutely no visual or acoustic contact with the audience at all.

8. If countermeasures are put into place to prevent all of the above there is still no absolute guarantee that a player is not receiving outside assistance. The simple reason is that there are other, even more subtle methods that can be employed. Since there is no known precedence for their use in chess I will not start a discussion of them here.

The conclusion of our studies is that from a technical point of view it is extremely difficult to guarantee that there will be no cheating in chess by the clandestine use of a computer at decisive points in the game. The closest one could get to absolute certainty would be by implementing very radical controls: one would have to introduce rigorous body checks, isolate the players completely from the outside world during the games, perhaps even keep the playing sites a secret until immediately before each game. Possibly the most effective method would be to broadcast the moves of a game only after it is over – if nobody outside the playing site has access to the moves while they are being played it becomes impossible to provide assistance by any of the methods discussed above.

There is one contemporary section to follow: in it we will introduce you to new tools

that have become available for checking engine correlation in any batch of chess games.

Previous reports

|

A history of cheating in chess (1)

29.09.2011 – Hardly a month goes by without some report of cheating in international chess tournaments. The problem has become acute, but it is not new. In 2001 Frederic Friedel contributed a paper to the book "Advances in Computer Chess 9". It traces the many forms of illicit manipulations in chess and, a decade later, appears disconcertingly topical and up-to-date. We reproduce the paper in five parts. |

|

A history of cheating in chess (2)

04.10.2011 – Coaching players during the game is probably the most widespread form of cheating (rivaled only perhaps by bribery and the throwing of games). Although this practice began long before the advent of chess playing machines, computers have added a new and dramatic dimension to this method of cheating in chess. You will never guess: who were the pioneers of cheating with computers? |

|

A history of cheating in chess (3)

18.12.2011 – In January 1999 the main topic of conversation amongst top players like Kasparov, Anand and others: who was the mysterious German chess amateur, rated below 2000, who had won a strong Open ahead of GMs and IMs, with wonderfully courageous attacking chess and a 2630 performance? How had he done it? Turns out it was with unconventional methods, as subsequent investigation uncovered. |

|

A history of cheating in chess (4)

28.2.2012– Las Palmas 1996: Garry Kasparov is agonizing over his 20th move against Vishy Anand. He calculates and calculates but cannot make a very tempting pawn push work. Immediately after the game he discovers, from his helpers, that it would have won the ultimately drawn position. The point that became clear to him: a single bit of information, given at the top level in chess, can decide a game. |

Cheating in chess: the problem won't go away

3/30/2011 – As you know the recent suspicion of organized cheating during a Chess Olympiad has led to three French players being suspended. One is currently playing in the European Individual Championship, where his colleagues have published an open letter demanding additional security. For years we have been proposing a remedy for this very serious problem. It needs to be implemented now.

Anti-cheating: the fifteen minute broadcast delay

5/13/2011 – For five years we have been trying to get FIDE to implement a 15-minute delay in the Internet broadcast of important games – to make organised cheating harder. A chess journalist has now pointed out a fatal flaw in the plan: it would force chess journalists to walk many yards to find out the current status of the games. Damn – and we thought it was such a good idea! What is your opinion?

Anti-cheating: the fifteen minute debate continues

6/29/2011 – Our recent reply to stern criticism leveled against us in the Dutch magazine New in Chess resulted, unsurprisingly, in a large number of letters from our readers, many quite effusive. But we decided not to publish any until at least one turned up supporting the views of our NiC critic. Six weeks went by until it at last came, authored by the critic himself. Now we can publish your letters.

Advances in Computer Games 9", edited by Professors H. J. van den Herik, University Maastricht, and B. Monien, University of Paderborn. It was published by the Universiteit Maastricht in 2001. The paper on Cheating was written and submitted by the author in 2000.

Advances in Computer Games 9", edited by Professors H. J. van den Herik, University Maastricht, and B. Monien, University of Paderborn. It was published by the Universiteit Maastricht in 2001. The paper on Cheating was written and submitted by the author in 2000.