Vera Menchik was the first and only woman before the Second World War who was able to compete on equal terms with most of the leading masters of her time. She was born on 16 February 1906 in Moscow. Today marks the 120th anniversary of her birth. Her father was Czech, her mother English. Her father worked as an estate manager for wealthy Russian families, her mother as a governess. In 1908, a second daughter, Olga, was born. The family was financially secure. They owned a house and also ran a mill as a secondary source of income. Vera and Olga were able to attend a private school.

The family's good fortune came to an end with the Russian Revolution. The mill was confiscated, and the Menchik family first had to share their house with other families before losing it altogether. The private school was closed, and Vera and Olga attended a state school instead. In the early years after the Revolution, pupils sat in thick coats by candlelight, as there was neither heating nor electricity.

During this time, their father taught his daughters to play chess. Vera was nine years old and soon began taking part in school tournaments.

In this video course, experts (Pelletier, Marin, Müller and Reeh) examine the games of Judit Polgar. Let them show you which openings Polgar chose to play, where her strength in middlegames were, or how she outplayed her opponents in the endgame.

In this video course, experts (Pelletier, Marin, Müller and Reeh) examine the games of Judit Polgar. Let them show you which openings Polgar chose to play, where her strength in middlegames were, or how she outplayed her opponents in the endgame.Because of the difficult living conditions, the Menchiks decided in the autumn of 1921 to leave post-revolutionary Russia, but they could not agree on a common destination. The couple separated. The father returned to Czechoslovakia. The mother moved to England with her daughters and went to live with her own mother in St Leonards-on-Sea, a suburb of Hastings.

For Vera and Olga, starting anew in England was very difficult, as they spoke only Russian and found it difficult to learn English. Vera in particular now devoted herself more intensively to chess, also as a way of participating in social life in her new surroundings.

In 1923/24, Vera Menchik played in the lowest section of the Hastings Christmas Congress and worked her way up to the higher sections in the following years. In 1929, she played for the first time in the Premier section alongside the masters.

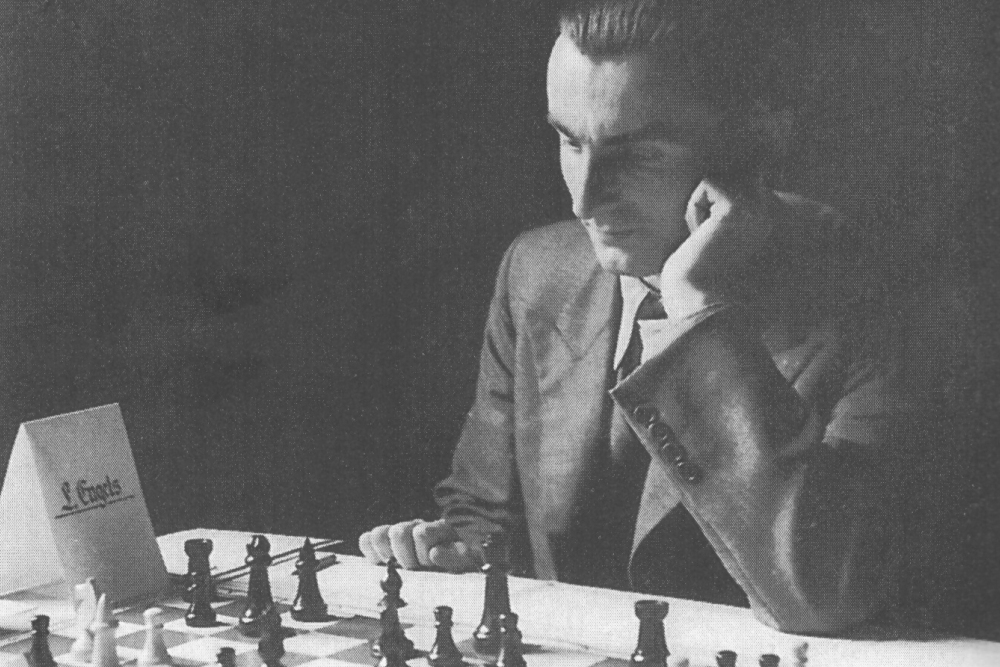

Vera Menchik

After turning 18, she was able to join the Hastings Chess Club in 1924. There she received training from Géza Maróczy, among others, who lived near Hastings for a time after the First World War and regularly visited the club. From Maróczy she learned the positional foundations of the game.

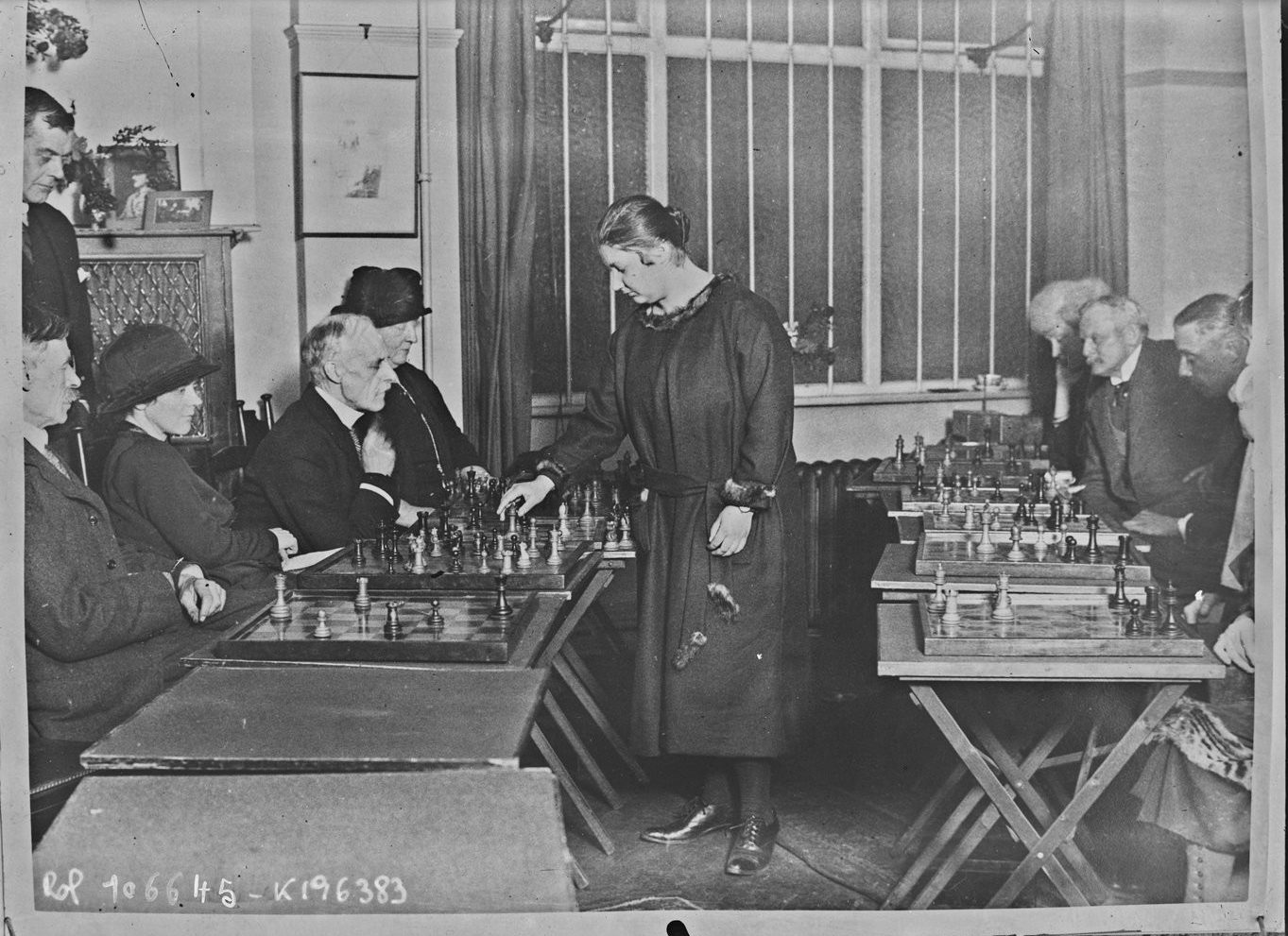

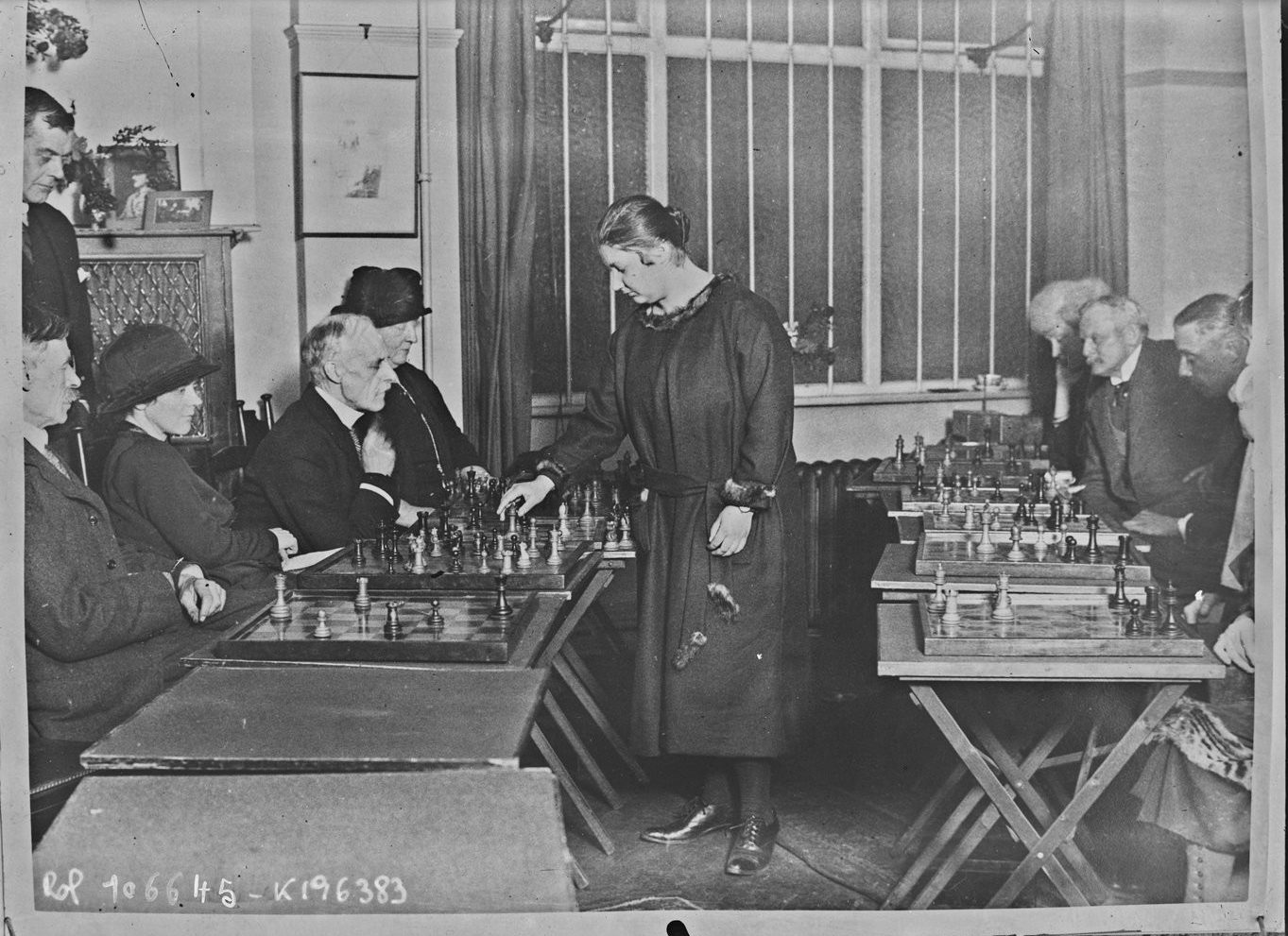

Two years later, the young Menchik was already capable of giving simultaneous exhibitions.

Simultaneous display at the Imperial Chess Club in London | Photo: Bibliothèque Nationale de France

In 1927, Vera Menchik won a women's tournament held alongside the Chess Olympiad, which was later recognised as the Women's World Championship. She claimed the first official Women's World Championship title in commanding fashion, scoring ten wins and one draw.

Menchik defended her world title six times before the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Across all those championships, she lost only a single game - in Hamburg in 1930 to Wally Hanschel -, drew just four games and won 78. She also won a World Championship match against Sonja Graf, though she lost two games in that encounter. The German player Sonja Graf was the only woman before the Second World War who was ever able to pose a real threat to Menchik. At the last championship before the war, in Buenos Aires in 1939, Menchik was lost in her game against Graf but eventually turned it around and defended her title with a two-point margin over her rival.

Apart from the Women's World Championships, there were practically no women-only tournaments before the Second World War. Menchik therefore had little choice but to compete in men's events. As she possessed the necessary strength, she was able to do so successfully.

She first gained major international recognition at a Scheveningen-system match between England and the Rest of the World in Ramsgate. Playing for the Rest of the World, she finished joint second behind Capablanca, level on points with Akiba Rubinstein.

Experts examine the games of Max Euwe. Let them show you which openings Euwe chose to play, where his strength in middlegames were, which tactical abilities he had or how he outplayed his opponents in the endgame.

Experts examine the games of Max Euwe. Let them show you which openings Euwe chose to play, where his strength in middlegames were, which tactical abilities he had or how he outplayed his opponents in the endgame.

Max Euwe became the fifth World Chess Champion after beating Alexander Alekhine in the 1935 World Championship match. A maths teacher by profession, Euwe remained an amateur throughout his life, but was still the best chess player in the Netherlands, and one of the world's best players. Euwe holds the record for the most Dutch national championships, with twelve. After winning the World Championship, Euwe was also the world's best player for a while. He lost the title again in 1937 in the rematch against Alexander Alekhine.

Free video sample: Openings

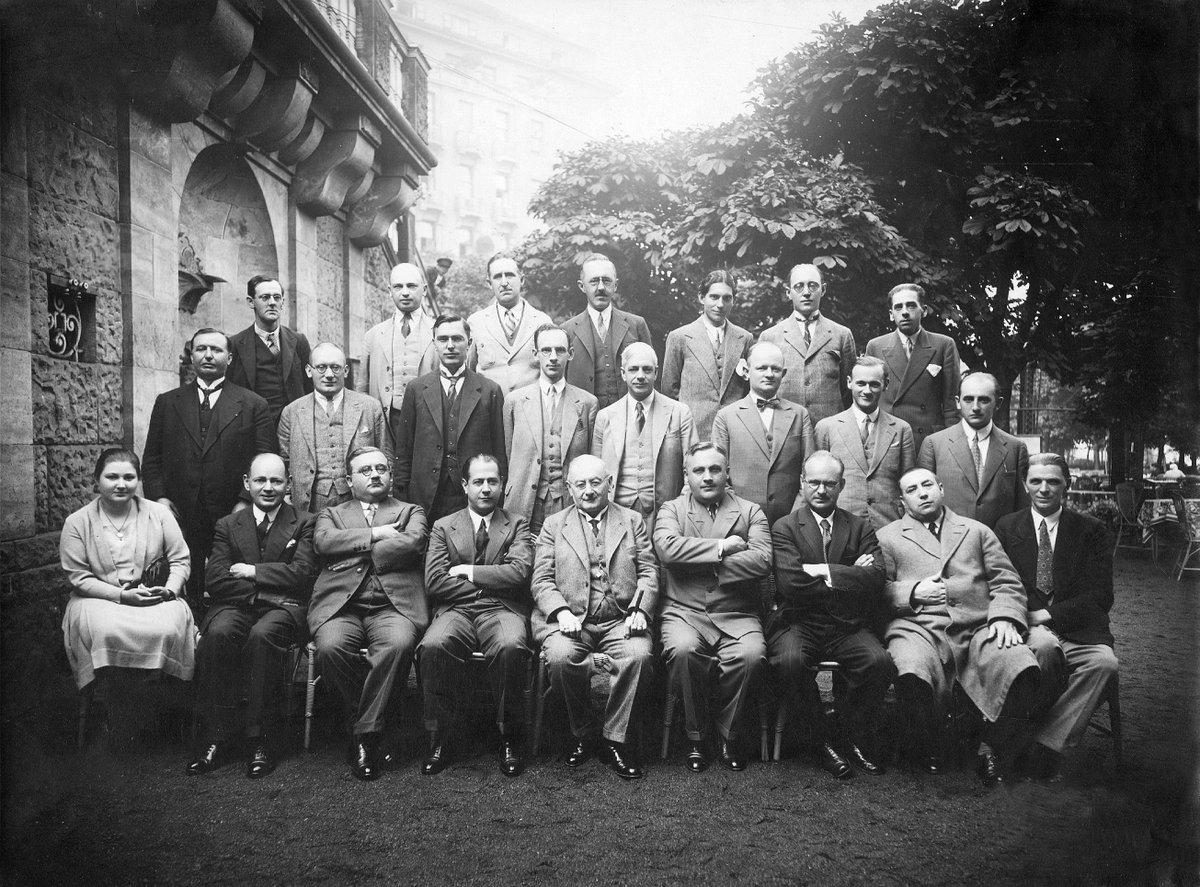

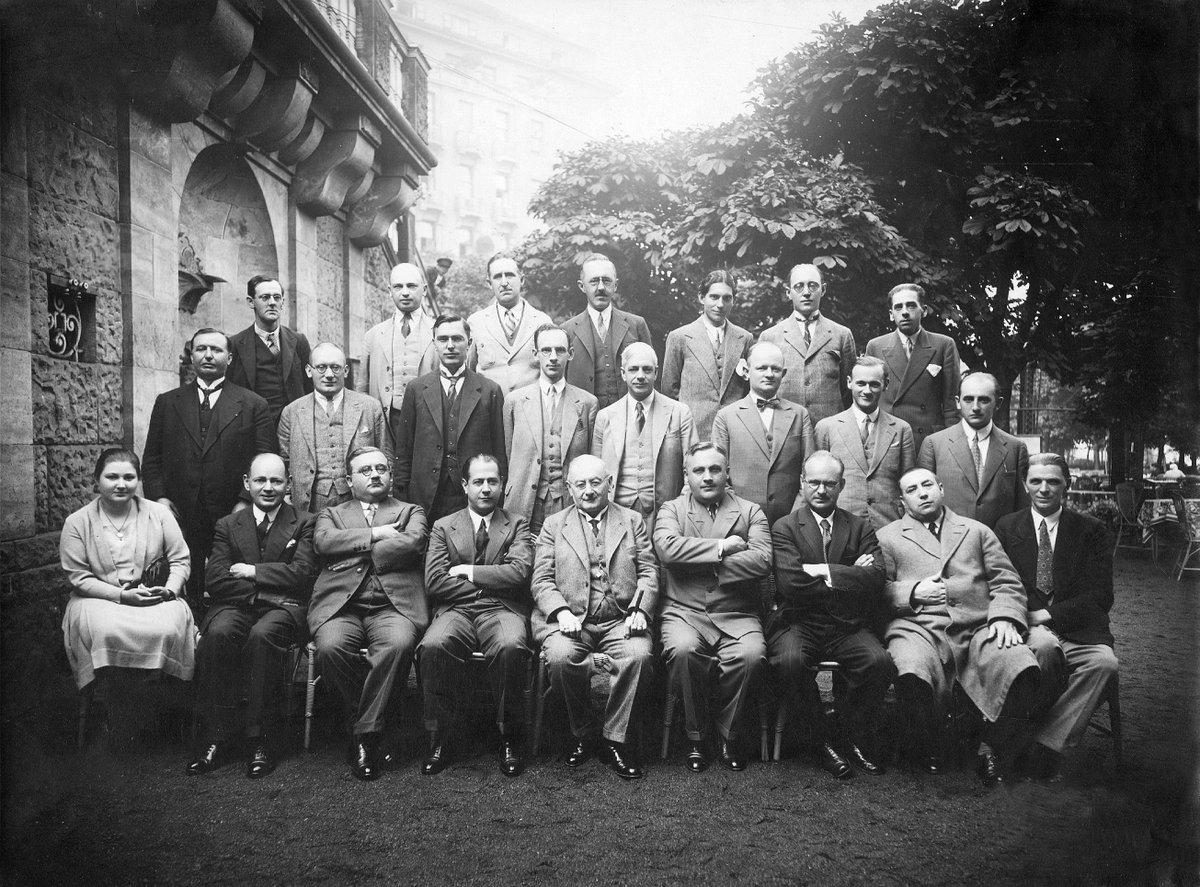

In 1929, she was invited to the super-tournament in Carlsbad, which featured the best players of the time. Only Lasker and Alekhine were absent.

Group photo with a lady among the masters

Menchik's participation prompted mocking remarks, as many did not consider her an equal player. Hans Kmoch declared in front of the other competitors that he would join a women's ballet company if Menchik scored more than three points. It was in this context that Albert Becker's famous quip arose - the suggestion to found a Vera Menchik Club, whose automatic members would be all those who lost to the world champion.

Kmoch was fortunate: Menchik scored three points, but no more. The ballet company was spared his services. Albert Becker, however, became the first member of the Menchik Club, having been comprehensively outplayed by her.

The tournament was won by Nimzowitsch with 15/21.

In the years that followed, several other prominent players unwillingly joined the Vera Menchik Club, including George Alan Thomas, who became a regular victim, the codebreakers C. H. O'D. Alexander, Stuart Milner-Barry and Harry Golombek, as well as Edgard Colle, Eugene Znosko-Borowsky, Max Euwe, Sultan Khan and Jacques Mieses. Against world champions Capablanca (0 out of 9) and Alexander Alekhine (0 out of 8), however, she had no success. She faced Emanuel Lasker only once, in Moscow in 1935, and also lost.

Nevertheless, world champion Alekhine himself wrote appreciative words about Menchik's play in his New York Times articles on the 1929 Carlsbad tournament:

I have so far refrained from passing a final judgement on Mrs Vera Menchik of Russia, as in the case of such an extraordinary person the utmost caution and objectivity are required in criticism. After fifteen games, however, it is clear that she is an absolute exception among women. She is so gifted at chess that with further work and tournament experience, she will surely develop from her present level of an average player into a high-class international master.

She has undeniably scored her three points against strong masters, but the public scarcely knows that she also achieved superior positions against Euwe, Treybal, Colle and Dr Vidmar. She was defeated by Dr Vidmar only after a nine-hour struggle. It is the duty of the chess world to grant her every opportunity for further development.

As a result, Menchik received further invitations to top-class tournaments in the following years. She usually finished in the lower half of the table, but she consistently managed to defeat established masters and occasionally even take half a point from one of the very greatest.

Through simultaneous exhibitions, the world's best woman chess player earned some additional income.

The Leningrad Dutch Defence is a dynamic and aggressive opening choice for Black, perfect for players who want to add some adventure and spice to their repertoire.

The Leningrad Dutch Defence is a dynamic and aggressive opening choice for Black, perfect for players who want to add some adventure and spice to their repertoire.

Vera Menchik plays against 20 opponents simultaneously at the Empire Social Chess Club in London, 1931

Vera Menchik performed truly poorly only at the 1935 Moscow tournament, where she finished last with just one and a half points. However, with a draw, she denied Salo Flohr sole victory in the event. In second-category events, by contrast, Menchik often finished near the top.

In England, Vera Menchik was regarded as a foreigner. Russian was her mother tongue, but Russia as a state no longer existed, and she had no connection with the Soviet Union. She therefore chose to play under the Czechoslovak flag, even though she did not live in Czechoslovakia and did not speak Czech. Menchik did, however, occasionally visit her father in Prague and took part in the Czechoslovak national championships in 1933 and 1936. Only through her marriage in 1937 to the 28-year-older official Rufus Stevenson did she obtain British citizenship. He died in 1943.

Vera Menchik's life ended tragically. On 26 June 1944, she was killed together with her sister and her mother when a V1 rocket struck their house during an air raid on London. Vera Menchik was only 38 years old.

Obituary in the British Chess Magazine, August 1944: