ChessBase 17 - Mega package - Edition 2024

It is the program of choice for anyone who loves the game and wants to know more about it. Start your personal success story with ChessBase and enjoy the game even more.

Those outside the world of chess would be surprised to hear that the game of chess, one of the world’s oldest, presents a list of champions barely over a hundred years long, two years shorter than American baseball’s. In contrast, the players of the Asian board games Shogi and Go honor their champions at least as far back as the 1600s.

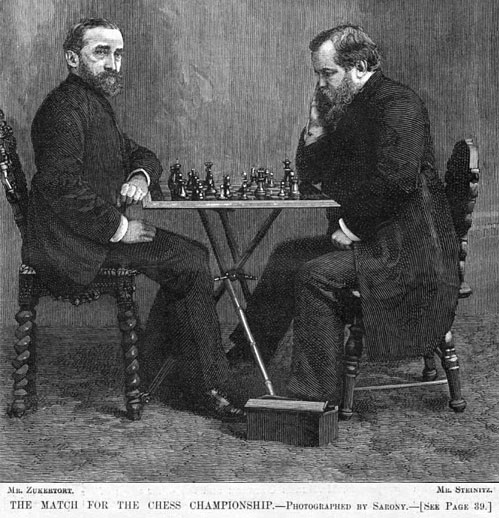

When Wilhelm Steinitz and Johannes Zukertort played their famous match in 1886, the match that eventually became accepted by FIDE as the first official chess world championship, the players had agreed that the winner would be declared “World Champion”. The other strong players accepted that, and the matter was settled. For the next sixty years, the world champion status – that of Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Euwe – rested on the same general acceptance by the chess world.

In 1948 FIDE took over the role of sanctioning the world championship, and compiled a list of “official” past world champions. But FIDE did not include the acknowledged champions prior to 1886 in their official history. I suggest that we ought to bring the earlier part of our championship history in from the cold by officially recognizing five great earlier champions, both to give those legendary players their due, and to give the game of chess the history it deserves. We are older than baseball.

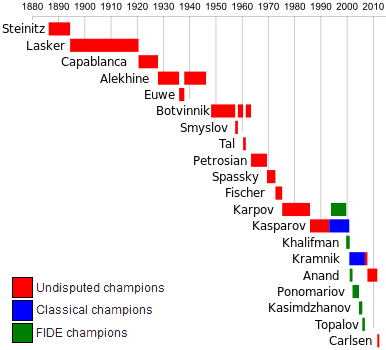

World Chess Champions [graphic by Wikipedia]

We have diminished our early history by not properly recognizing the great players who were in their time accepted as champions of the chess world. For example, the English master Henry Bird wrote from his personal experience, in Chess History and Reminiscences (1892), that Howard Staunton in the 1840s was “the admitted world’s champion in chess, until the title was wrested from him by Professor Anderssen … [in] 1851.” Clearly, their contemporaries recognized both Staunton and Anderssen as world champions in their time. Recognition as the champion of chess, from the late 1700s on, was in most cases the result of a match against the best of the rest, and was not essentially different from the 1886 match between Steinitz and Zukertort that we have accepted as a world championship match.

We have diminished our early history by not properly recognizing the great players who were in their time accepted as champions of the chess world. For example, the English master Henry Bird wrote from his personal experience, in Chess History and Reminiscences (1892), that Howard Staunton in the 1840s was “the admitted world’s champion in chess, until the title was wrested from him by Professor Anderssen … [in] 1851.” Clearly, their contemporaries recognized both Staunton and Anderssen as world champions in their time. Recognition as the champion of chess, from the late 1700s on, was in most cases the result of a match against the best of the rest, and was not essentially different from the 1886 match between Steinitz and Zukertort that we have accepted as a world championship match.

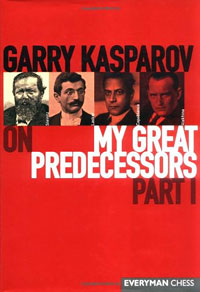

A fairly clear history of world champions, so recognized in their time, goes back nearly a century and a half before the Steinitz-Zukertort match – back to François-André Danican Philidor. I think most chess players and aficionados would agree with Garry Kasparov, who in volume 1, chapter 1 of My Great Predecessors identified the preeminent players who dominated chess before Steinitz. (In quoting Kasparov below I’m not suggesting that he has recommended treating these earlier players as official world champions. He has not, as far as I know. He has simply confirmed their dominance, and I am quoting Kasparov’s book as a convenient reference.) Kasparov is not alone in holding that these specific players were dominant in their time. Many sources name the same players.

On the wall here in the Oslo Schakselskap there has long hung portraits of

all the world champions, “official” or not, starting with Philidor.

The quotes below, labeled “MGP”, are from My Great Predecessors, v.1. I am quoting Kasparov out of context, but I hope not contrary to his meaning. The list, then, of unacknowledged world champions who deserve to be given their due as official world champions of chess.

France, and the Café de la Régence in Paris in particular, was the center of the chess world in the 18th century. In the latter half of the century Philidor was acknowledged there and throughout Europe as the game’s champion. MGP: “In a match in 1747 he crushed the talented Syrian player Stamma ...

Philidor was so much stronger than his contemporaries, that from that point until the end of his life he played them all, only by giving away odds.”

IM Almira Skripchenko points to a very important figure on the facade of the Paris Opera

The above photos were taken by Frederic Friedel. The following notes appeared in the 2004 report:

François-André Danican Philidor (born Sept. 1, 1726, died August 31, 1795) was a composer of classical music who became the strongest chess players of his day. The name Philidor was passed on through his grandfather from King Louis XIII, a tribute to this family of royal musicians.

During years of waiting to perform in the chapel of Versailles, the young Francois learned the moves of chess and became the best player in the chapel. Philidor supported himself by giving music lessons, arranging and copying music. Spare time was spent at the Cafe de la Regence in Paris. There he learned from the strongest player in France, M. de Kermur, Sire de Legal. In 1745, Philidor went to Rotterdam and then to London accompanying a music company.

Due to unexpected cancellation of the concerts, his focus shifted to chess to earn a living. During 1747, he played a ten-game match with Phillip Stamma one of the strongest players of his time. He gave him odds of a move, and a drawn game would count as a win for Stamma. Philidor trounced Stamma with a score of eight wins, one draw and one loss. When he was in his prime, few opponents could challenge him without receiving odds or placing him under a blindfold. Often he would play two or three blindfolded at the same time. His published chess strategy, "L'Analyse du Jeu des Echecs", stood for a hundred years without significant addition or modification. He preached the value of a strong pawn center, an understanding of the relative value of the pieces, and correct pawn formations. We still remember his motto, that "pawns are the soul of chess." Unfortunately, none of his games from his prime exist today.

Philidor died in London, after being denied a passport to return to France for a demonstration match. The newspaper obituary read "On Monday last, Mr. Philidor, the celebrated chess player, made his last move, into the other world."

We should recognize François-André Philidor as World Champion from his match win over Stamma in 1747 to his death in 1795.

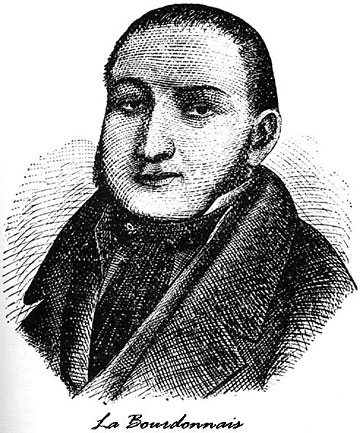

We may accept a break in the world championship from Philidor’s death in 1795 to 1824, as there was from Alekhine’s death in 1946 to 1948, though it may be worth considering Alexandre Deschapelles as champion for part of this time, around 1820. Kasparov writes in MGP: “After the death of Philidor, for a long time there was no clearly strongest player in Europe.” And then: “… in 1824, on a visit to London, La Bourdonnais crushed the English masters and was proclaimed by his compatriots as ‘the greatest chess player in Europe.’”

La Bourdonnais was born on the French colony of La Réunion in 1795, the year of Philidor’s death, and like Philidor he grew to become the strongest player at the Café de la Régence, after defeating his teacher Deschapelles in 1821. After his 1824 London victories, no worthy challenger to La Bourdonnais appeared until 1834, when he received a challenge from Alexander McDonnell of Ireland, the strongest player in the British Isles, to contest a match for the right to be considered the world’s best player.

The contest against McDonnell, an exhausting series of six matches (85 games), was played from June to October, 1834, at the Westminster Chess Club in London, and has become La Bourdonnais’ greatest chess legacy. He won four of the matches, McDonnell won one, and the sixth match was broken off – it’s unclear just why – with McDonnell leading 5 wins to 4. Overall, La Bourdonnais won a clear victory with 45 wins against 27 losses and 13 draws. These matches were ground-breaking as the first significant chess contest where each move of every game was recorded and preserved for posterity.

Henry Bird (1892, cited above) writes of La Bourdonnais, Anderssen and Morphy, that “these are probably the three greatest players which the world has produced since … the sixteenth century.”

We should recognize Louis de La Bourdonnais as World Champion from his London success in 1824 to his death in 1840.

– Who are the next unrecognized World Champions? Find out in part two –