“We have met, gentlemen to do honour to our young friend who has honoured us and all who glory in the name of Americans, as the hero of a long series of bloodless battles, won for our common country. I propose the health of Paul Morphy, the world’s Chess Champion: His peaceful battles have helped to achieve a new revolution; his youthful triumphs have added a new clause to the declaration of American Independence!”

“We have met, gentlemen to do honour to our young friend who has honoured us and all who glory in the name of Americans, as the hero of a long series of bloodless battles, won for our common country. I propose the health of Paul Morphy, the world’s Chess Champion: His peaceful battles have helped to achieve a new revolution; his youthful triumphs have added a new clause to the declaration of American Independence!”

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Boston, May 31st, 1859.

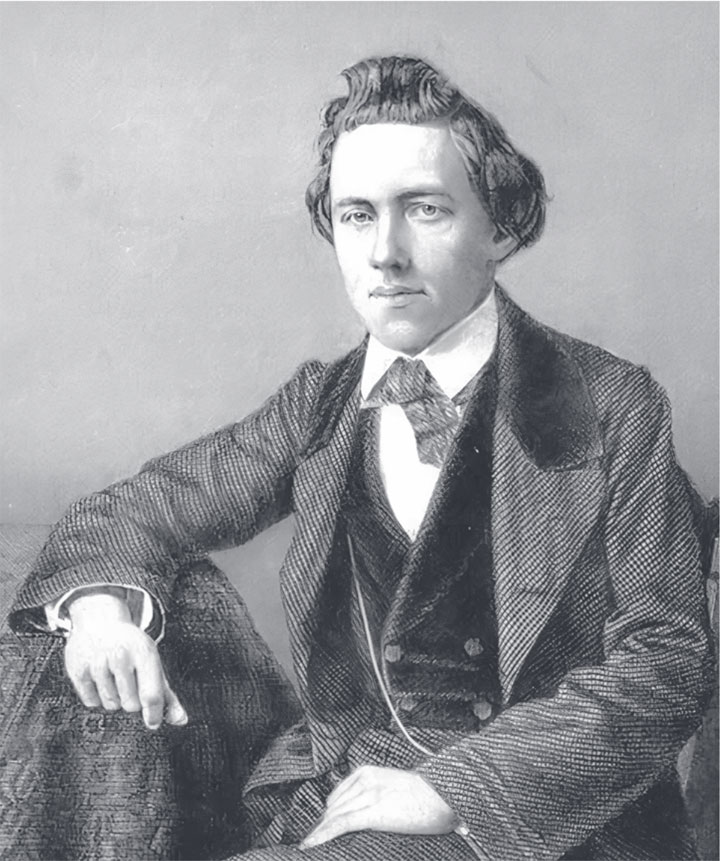

“Paul Morphy is an object of pity,” wrote the New York World in 1877. “He is sane on a few subjects, but his old hobby – chess – is so distasteful to him that he cannot bear to talk about his former exploits. It would really be an act of charity to remove him from the public gaze.”

There have always been differing interpretations as to why the finest player of the age should so abruptly and irrevocably turn his back on the game, and his descent from extraordinary celebrity, feted by the lions of American culture, into local oddity has long been the subject of considerable speculation. Three very different and competing views are examined in this article:

- Charles Hertan, The Real Paul Morphy: His Life and Chess Games, New In Chess, 2024.

- Ernest Jones, ‘The Problem of Paul Morphy’, The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, January 1931.

- Frances Parkinson Keyes, The Chess Players, Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1960.

Far fewer doubts exist as to Morphy’s playing ability. While some, including Fine, Chernev and Hooper, thought him overrated, others had no reservations. Capablanca was particularly effusive. During the St. Petersburg tournament of 1914 the English master Amos Burn wrote of one of Capablanca’s combinations: “A beautiful move which irresistibly reminds one of Morphy, to whose style of play that of the young Cuban undoubtedly bears a very great resemblance”.

A delighted Capablanca responded: “Playing like Morphy means playing like nobody else”, and “the magnificent American master had the most extraordinary brain that anybody has ever had for chess. Technique, strategy, tactics, knowledge which is unconceivable for us; all that was possessed by Morphy fifty-four years ago”.

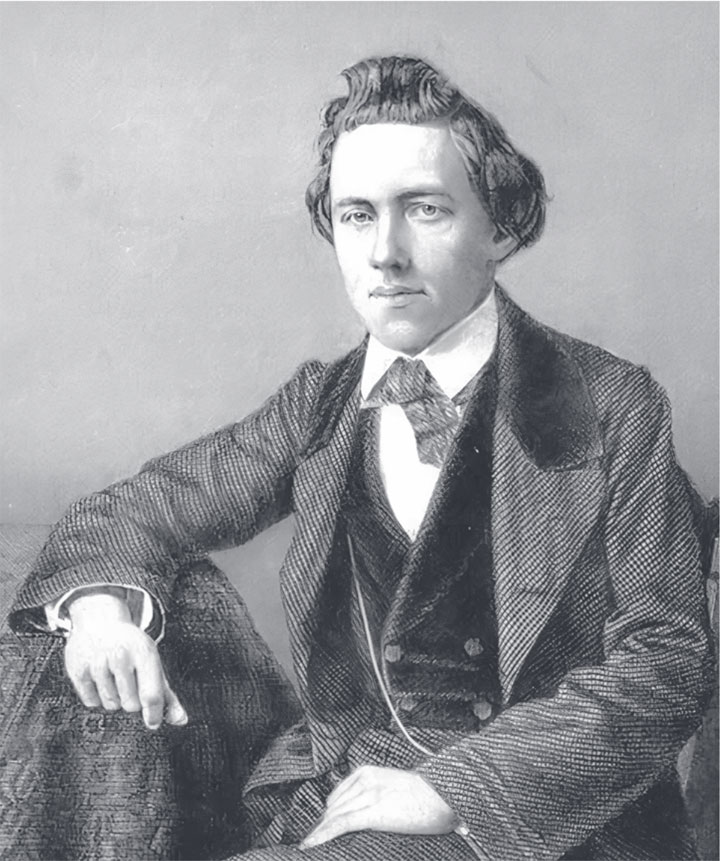

The path of Morphy’s competitive career, which lasted barely two years between winning the inaugural US Chess Congress in November 1857 at the age of 20 and defeating all the best that Europe had to offer by April 1859, is too well known to pursue in detail. Suffice it to say that, owing to the grace, precision and élan of Morphy’s play and demeanour, for most it was a joy to lose to him. In the words of Dr. Ernest Jones, one of Freud’s inner circle and the first to attempt a serious evaluation of Morphy’s collapse, it “reads like a fairy tale”, though, it would appear, one with all the psychic turbulence and violence that such tales contain.

Indeed, following his return to the US, Morphy enters into an agreement with his mother to renounce chess for monetary stakes, absconds to Paris during the Civil War, is rejected in love, and fails miserably in his two attempts at setting up a law practice in his native New Orleans. Even discussing chess becomes anathema to him, and, for at least a decade prior to his death in 1884, his life was lost to purposeless routine; one of paranoia, voyeurism and hallucinations.

Conceptual Variants

Essentially two main strands of thought can be identified with regard to Morphy’s breakdown. One must bear in mind, however, that it is the great minefield of chess history; the question of Keres throwing his first four games against Botvinnik in the world match tournament of 1948 comes a distant and straightforward second, resolved by his asking of the Soviet authorities, “Will they cut off my head?”

Firstly, the Freudian view sees the unhappy encounter with the father-imago, Howard Staunton, as unmasking the subliminal role that chess played in containing problematic impulses in Morphy’s psyche, resulting in a collapse of both moral and mental integrity. Certainly less vivid is the more modern view, subscribed to by Charles Hertan in his new book, The Real Paul Morphy, which argues that the main cause of his paranoia was constitutional, determined by hereditary predisposition, and which can effectively be deemed an accident of nature.

A further approach is also worth considering, one which seeks to imagine – through an imagination ‘properly controlled’ and bolstered by immersion in the period itself – what occurred in the various and extensive gaps in Morphy’s biography, notably during the US Civil War, which led to a catastrophic shock in 1865 and from which he never recovered.

Ernest Jones’s argument, presented in a celebrated lecture in 1930, sees chess as acting as a substitute for warlike, patricidal impulses and that prior to his European triumphs, chess proved an untroubled sublimation of such unresolved conflicts within Morphy’s psyche. The relations with Harrwitz and in particular Staunton, however, exhibited to Morphy that his aim of defeating both “was a disreputable one”. This Staunton achieved through effectively calling Morphy a penniless adventurer, a professional no less, and that he had far more serious, i.e. grown up, matters to attend to, namely his Shakespearean studies. By this argument, Morphy’s sublimation of father-murder through chess was unmasked, and the idea of the game proceeding from the most honourable incentives could never be retrieved.

While Jones thought Morphy’s increasingly aggressive and obsessional behaviour was due to the loss of the subliminal effects of chess – hostile impulses were no longer contained and were turned outwards, such as physical attacks on friends and his pre-occupation with being denied his inheritance by his brother-in-law – Hertan believes these were due to a chemical imbalance in the brain. Though Hertan dismisses Freudian interpretations as “worthy of little more than a good laugh and about as therapeutic as the leeching Morphy received in Paris before playing Anderssen” – a rather glib observation – he at least pulls no punches in presenting the extent of Morphy’s problems.

David Lawson, in his extensive biography Paul Morphy: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess (David McKay, 1976), thought “The mental disorder which descended upon him, incidentally seeming to clear up in the last year or two of his life, during which he occupied himself with his reading, daily walks, and visits to his brother’s house.” However, the day after Morphy’s death, the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Every fair day his trim little figure, clad in the height of snug-fitting fashion, might be seen swinging his little cane on the boulevards, scrutinizing through his glass the fair promenaders. What would have been impertinence in others was pardoned in Paul, and for years he thus passed his useless life away, unmolested and unmolesting. Even so late as yesterday he was seen on Canal Street chattering to himself and smiling at his own conceits”.

Lacunae

As mentioned, various gaps in Morphy’s life persist and Lawson, for example, dares nothing that isn’t nailed down. Frances Parkinson Keyes’s novel, The Chess Players, takes an entirely different tack and, in seeking to ensure that Morphy’s fame should never die, asks how in the absence of a definitive biography this could be achieved. Her answer: “Through a thoughtful and comprehensive novel, the work of a writer who will make use of all known facts about the protagonist, and who, when straying into the field of fiction, will try to correlate the real with the imaginary in such a way that the connection between the two will seem not only possible but plausible”.

Collaboration was crucial to Keyes’s success as a writer, relying on knowledgeable individuals to help with her extensive research, and, steeped in Louisiana and Confederate history, familiarity with many of the participants, not to mention a close reading of Jones, the correlation of real and imaginary proves remarkably successful. Central to the story is the unhappy love affair that Morphy embarked on while still in his teens with an ambitious and insincere young woman, Charmian Sheppard, who though wealthy, was seen as a “shopkeeper’s’ daughter” and wholly unsuited to the reserved aristocratic Morphy. While fictitious, she is based on a real person, and evidence mounts that his feelings are not reciprocated, and, on the very evening of the Boston celebrations, she informs him of their difference in class, his seeming sexual inadequacy and that she would “never marry a mere chess player!”

His attempts to set up a law practice fail for the same identification with the game, and, now desperate to prove himself, in 1862 Morphy becomes a Confederate agent in Paris with the aim of inducing Napoleon III to recognise the Confederacy as an independent nation, and Commissioner John Slidell believes Morphy’s popularity with the French – remember those scenes of near rioting outside the Café de la Régence following one of his blindfold displays – will prove highly useful.

While traditional biographies fill this three-year gap with next to nothing – Hertan, for example, only mentions abortive attempts to get Morphy to play in tournaments – Keyes envisages a “glittering and corrupt world of dazzling political hostesses, venal politicians and influential courtesans”. Again, as Keyes points out in her postscript, “Benjamin, Beauregard and Slidell were all family friends”, and the “occupation assigned to him during this period seemed not only logical but inescapable to me”.

Slidell also believes that Morphy’s chess will prove an asset, but the opposite is true: the openness and honesty of his character, fully displayed in his playing style – like Capablanca he never dissembled – are quite out of place in the underhand world of spying. In Paris he is reacquainted with Charmian, now married to a sadistic French Prince, and in a terrible denouement is lured to a final tryst by a false note. Hoping to rescue her, he instead finds her “lying naked on blood-stained sheets [...] Nothing remained of her beautiful face but a pulpy mass of battered flesh. She had been beaten to death”. The Prince, aware of their relationship, had killed her and then poisoned himself.

As Keyes said in an endnote, “We also know that, before leaving Paris in 1865, Paul Morphy suffered some sort of a severe shock”, and for her only an event of such magnitude could have been the cause. In a brief final chapter, on the day of his death, Morphy is going about his empty routine, and, sickened of the stares and hushed voices, returns to the family home and suddenly overthrows the chess table in the middle of his room, scattering the pieces before taking a cold bath after walking in blazing heat, knowing it will be fatal.

Endnote

Whichever version one subscribes to, it’s a heartbreaking story, and for this reviewer only one author is up to the task of telling it. Jones’s viewpoint cannot be dismissed as laughable, though as Alexander Cockburn states, “In his zeal to emphasize the central point of his observations – that of father-murder – Jones simplified certain points and perhaps laid insufficient emphasis on others”, notably social causes and the effects of being a prodigy.

Unfortunately, Hertan’s prose proves somewhat ill-written and, when dealing with Morphy’s forebears for example, dull. He does, however, fully succeed in conveying the excitement and adventure of the US Chess Congress and the European triumphs, though it would be difficult not to as it’s the most exhilarating chapter in the history of the game. Annotations are kept brief, to the point and fully in keeping with the age, though lapses such as “exclams”, “young phenoms”, “Magnus”, and Morphy’s “monster technique”, appear out of place in a historical work.

Keyes’s book, on the other hand, while occasionally straying into an excess of detail of dress, manners and food, which apparently her considerable audience rejoiced in, is a thrilling and sustained blend of knowledge and controlled imagination, and has been unjustly neglected. Her interpretation offers Morphy far more honour, energy and intrigue than a slow, congenital descent into paranoia, voyeurism and delusions. In short it reclaims him. Read Hertan for the chess, but read Keyes for the life.

About the author

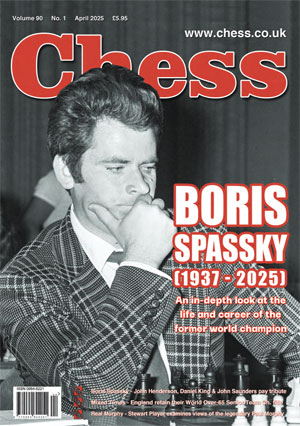

Stewart Player is a healthcare policy analyst and chess historian living in Edinburgh. He has written several book reviews for 'CHESS' magazine as well as some contentious articles, notably one arguing that Spassky threw the 1972 World Championship Match.

About CHESS Magazine

The above feature is reproduced from Chess Magazine April/2025, with kind permission.

CHESS Magazine was established in 1935 by B.H. Wood who ran it for over fifty years. It is published each month by the London Chess Centre and is edited by IM Richard Palliser and Matt Read.

The Executive Editor is Malcolm Pein, who organises the London Chess Classic.

CHESS is mailed to subscribers in over 50 countries. You can subscribe to it here.

You should also take a look at our Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy. In it our team of experts gets to the bottom of the “Morphy myth” and in about five hours of video running time they cast light on the most important facets of his ability. One focal point in this is Oliver Reeh’s “Tactics column”: you are invited in 20 interactive training videos to look into Morphy’s legendary combinatory skill over the board. But don’t worry, the International Master from Hamburg helps you find the solutions with tips and video feedback on your moves and ideas! In addition Jonas Lampert describes for you Morphy’s opening repertoire and explains the concepts which underpin the course of the game. Grandmaster Mihail Marin has examined the American’s strategic play and comes to a surprising conclusion: in no way does his positional understanding lag behind his tactical ability! And last but not least endgame expert Karsten Müller works out the strengths and weaknesses in Morphy’s endgame technique. On the DVD you will find all the games of the genius from New Orleans as well as a detailed biography by Thomas Eichhorn.

You should also take a look at our Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy. In it our team of experts gets to the bottom of the “Morphy myth” and in about five hours of video running time they cast light on the most important facets of his ability. One focal point in this is Oliver Reeh’s “Tactics column”: you are invited in 20 interactive training videos to look into Morphy’s legendary combinatory skill over the board. But don’t worry, the International Master from Hamburg helps you find the solutions with tips and video feedback on your moves and ideas! In addition Jonas Lampert describes for you Morphy’s opening repertoire and explains the concepts which underpin the course of the game. Grandmaster Mihail Marin has examined the American’s strategic play and comes to a surprising conclusion: in no way does his positional understanding lag behind his tactical ability! And last but not least endgame expert Karsten Müller works out the strengths and weaknesses in Morphy’s endgame technique. On the DVD you will find all the games of the genius from New Orleans as well as a detailed biography by Thomas Eichhorn.

Order the Master Class: Paul Morphy here.

“We have met, gentlemen to do honour to our young friend who has honoured us and all who glory in the name of Americans, as the hero of a long series of bloodless battles, won for our common country. I propose the health of Paul Morphy, the world’s Chess Champion: His peaceful battles have helped to achieve a new revolution; his youthful triumphs have added a new clause to the declaration of American Independence!”

“We have met, gentlemen to do honour to our young friend who has honoured us and all who glory in the name of Americans, as the hero of a long series of bloodless battles, won for our common country. I propose the health of Paul Morphy, the world’s Chess Champion: His peaceful battles have helped to achieve a new revolution; his youthful triumphs have added a new clause to the declaration of American Independence!”

You should also take a look at our Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy. In it our team of experts gets to the bottom of the “Morphy myth” and in about five hours of video running time they cast light on the most important facets of his ability. One focal point in this is Oliver Reeh’s “Tactics column”: you are invited in 20 interactive training videos to look into Morphy’s legendary combinatory skill over the board. But don’t worry, the International Master from Hamburg helps you find the solutions with tips and video feedback on your moves and ideas! In addition Jonas Lampert describes for you Morphy’s opening repertoire and explains the concepts which underpin the course of the game. Grandmaster Mihail Marin has examined the American’s strategic play and comes to a surprising conclusion: in no way does his positional understanding lag behind his tactical ability! And last but not least endgame expert Karsten Müller works out the strengths and weaknesses in Morphy’s endgame technique. On the DVD you will find all the games of the genius from New Orleans as well as a detailed biography by Thomas Eichhorn.

You should also take a look at our Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy. In it our team of experts gets to the bottom of the “Morphy myth” and in about five hours of video running time they cast light on the most important facets of his ability. One focal point in this is Oliver Reeh’s “Tactics column”: you are invited in 20 interactive training videos to look into Morphy’s legendary combinatory skill over the board. But don’t worry, the International Master from Hamburg helps you find the solutions with tips and video feedback on your moves and ideas! In addition Jonas Lampert describes for you Morphy’s opening repertoire and explains the concepts which underpin the course of the game. Grandmaster Mihail Marin has examined the American’s strategic play and comes to a surprising conclusion: in no way does his positional understanding lag behind his tactical ability! And last but not least endgame expert Karsten Müller works out the strengths and weaknesses in Morphy’s endgame technique. On the DVD you will find all the games of the genius from New Orleans as well as a detailed biography by Thomas Eichhorn.