When Spassky discovered chess, he was nine years old. His biographer Andrew Soltis writes:

One day Spassky’s older brother took him to Kirov Park [in Leningrad] ... and they found the chess pavilion, a common feature in large Soviet-era parks. ... Spassky remembered it had “a glass veranda surrounded by trees” with “a large black knight in front”: “It was marvelous weather. The wind from the bay of Finland played with the birch leaves, the sad northern sun shone on the glass of the veranda”. There was no one inside but he was mesmerized by the tables, boards and pieces. “I was seeing a fairy tale world... I lost my sense of reality... A wild passion took possession of me. ... Looking back, I had a sort of predestination in my life. ... I understood that through chess I could express myself and chess became my natural language”.

(Andrew Soltis, Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Korchnoi: A Chess Multibiography with 207 Games, McFarland 2019, p. 33)

That was in 1946, shortly after the Second World War, which had a lasting impact on Spassky’s life. Spassky was born on 30 January 1937 in Leningrad, the city besieged by the German army during the war from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944. The Wehrmacht wanted to starve Leningrad, and it is estimated that about 1.1 million people died during the siege, most of them from hunger and debilitation.

But shortly before the German siege ring closed around Leningrad, Spassky was able to escape with his brother to Perm, where he was placed in an orphanage. But when his parents picked him up in the summer of 1943, he was on the verge of starvation and, as he later confessed, could barely stand on his feet.

After the reunion, Spassky’s parents initially went to Moscow with their children, but when his father left the family, Spassky moved back to Leningrad with his mother and siblings, where they lived in abject poverty.

Chess offered Spassky an escape from this world of poverty, and once the royal game had captivated him in Kirov Park, the magic of the game never left him.

He returned to the pavilion the next day, and the day after that. He was there from the hour that the pavilion opened to when it closed at 9 p.m. ... “I had to play every day. I couldn’t do anything else”. (Soltis, p. 33)

Spassky’s enthusiasm for chess and his talent made him one of the best players in the Soviet Union within a short time, and already in 1948, at the age of only ten, he received a rarely awarded state scholarship for his success as a chess player, with which he was able to support his family.

Boris Spassky in 1948

As early as 1952, he qualified for the semifinals of the USSR Championship, where he obtained a fifty-percent score, and in 1953 FIDE awarded him the title of International Master. In 1955 he became World Junior Champion, and in the same year he qualified for the Candidates Tournament in Amsterdam to be played in 1956, where he finished in 3rd-7th place.

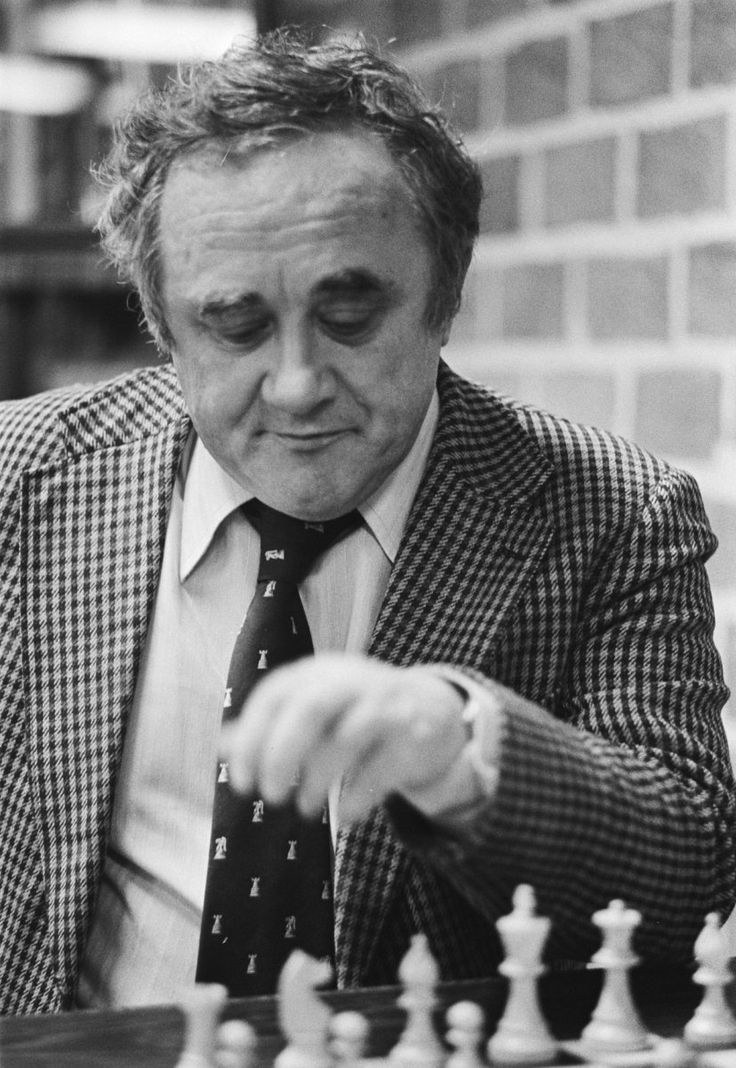

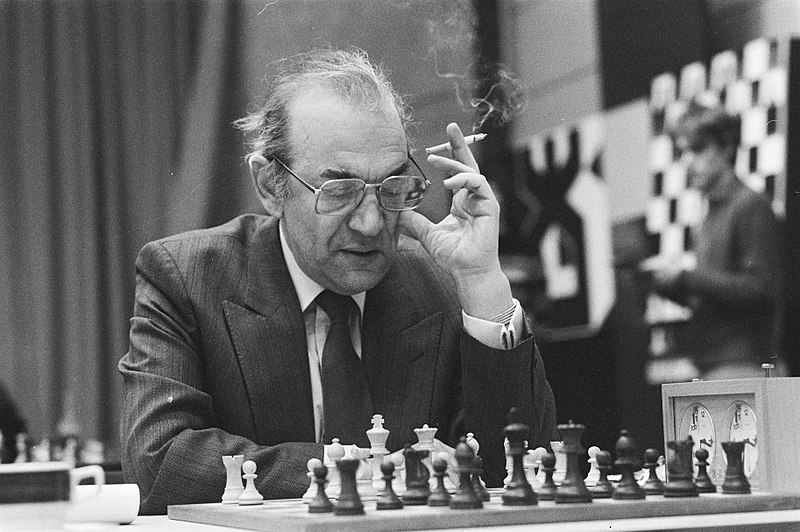

Boris Spassky | Photo: Herbert Behrens / Anefo; / CC BY-SA 3.0 NL

But this rapid rise was followed by a long period of stagnation, and it was not until eight years later, at the 1964 Interzonal Tournament in Amsterdam, that Spassky qualified again for the Candidates Tourneament.

In the 1958 USSR Championship, which was also a qualifying tournament for the Interzonal Tournament, on the other hand, he fell just short. However, he won the beauty prize in that tournament — for a brilliant victory in a Sicilian.

In the 1965 Candidates Matches, Spassky knocked out Paul Keres (5½-4½), Efim Geller (5½-2½) and Mikhail Tal (7-4), and thus gained the right to challenge Tigran Petrosian for the World Championship title in 1966. Spassky lost the match by a narrow margin of 11½-12½, but as the loser of the World Championship match he automatically qualified for the next edition of the Candidates. And he was successful again: he first knocked out Geller (5½-2½), then Bent Larsen (5½-2½) and finally Viktor Korchnoi (6½-3.½) — he was thus allowed to challenge Petrosian for the World Championship title for a second time.

This time things worked out better than three years before: in the second attempt, Spassky won 12½-10½ and thus became the 10th World Champion in chess history. On the way to the coveted World Championship victory, Spassky won a few brilliant games against the Sicilian at decisive moments.

In the quarterfinals of the 1968 Candidates Tournament, Spassky met Efim Geller, an outstanding theoretician who, however, often found himself in time trouble in his search for the best move. That was his undoing against Spassky.

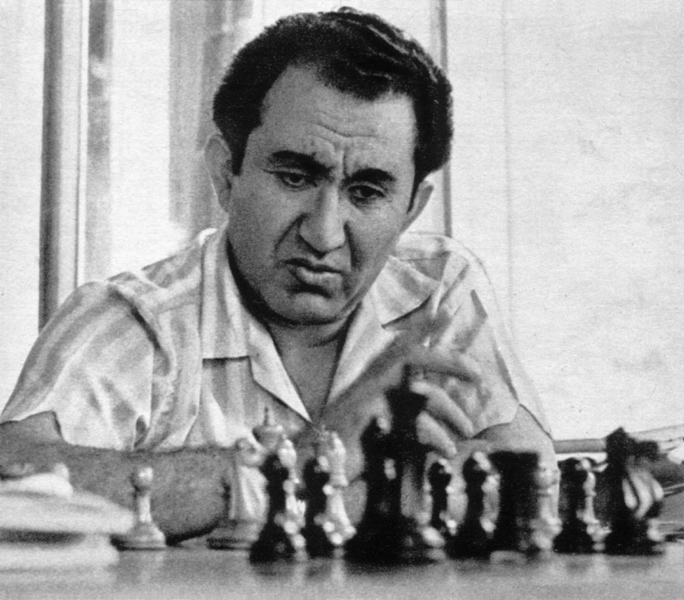

Efim Geller (unidentified photographer)

Five games of the match ended in draws, while Spassky won three times. In all three games Spassky had white and in all three games a Closed Sicilian appeared on the board. In the first two of these Sicilian games, Geller temporarily had a clear advantage — if not a winning position — but in time trouble he spoiled his positions and ended up losing. In the third and last Sicilian game of the match, Spassky scored a convincing victory with the help of a brutal mating attack.

At the 1969 World Championship match against Petrosian, Spassky also obtained a victory in the Sicilian in a deciding moment, which was as brilliant as it was important.

Tigran Petrosian — World Champion from 1963 to 1969

Three years later, Spassky had to defend his title against Bobby Fischer in the legendary 1972 World Championship match in Reykjavík. The match made headlines all over the world and took an unusual course due to Fischer’s airs and graces. In the first game, Fischer captured a poisoned pawn in an even position and shortly afterwards lost his bishop. He could not hold the difficult ensuing endgame, and so Spassky took a 1-0 lead.

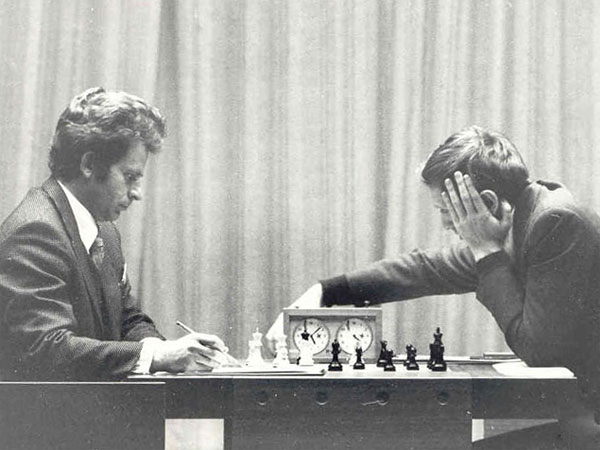

A legendary confrontation — Spassky versus Fischer, Reykjavík 1972 | Photo: Icelandic Chess Federation / Skáksamband Íslands

Fischer did not play the second game in protest against the allegedly overly loud cameras on stage and lost by forfeit — the competition was about to be abandoned, it seemed. But Fischer was persuaded to play the third game, when he defeated Spassky for the first time in his career. Including the first game of the 1972 match, the two had previously played six times against each other, with Spassky winning three and drawing three.

But after his victory in the third game, Fischer played as if unleashed, and scored 5½ points in the next seven games, which gave him a commanding 6½-3½ lead. If Spassky wanted to have any chance of turning the tide again, he needed a victory as quickly as possible. And that is exactly what he achieved in the eleventh game of the competition: as in the seventh game, Spassky went for the double-edged Poisoned Pawn variation in the Najdorf Sicilian, one of Fischer’s favourite variations. Fischer had analysed this provocative variation in detail and achieved a series of sensational victories with it before the match, but in the eleventh game Spassky upset the American with a surprising knight retreat — 14.Nb1. Fischer found no convincing answer and suffered one of the most crushing defeats of his entire career.

Boris Spassky in Reykjavík, 1972 | Photo: Icelandic Chess Federation / Skáksamband Íslands

But Spassky was unable to win another game against Fischer in Reykjavík in the remainder of the match, and so the competition finally ended after 21 games with a 12½-8½ victory for the American. Fischer had become the eleventh World Champion in chess history.

Fischer’s victory in Reykjavík upset the Soviet chess world, and the Soviet authorities did everything they could to recover from the defeat. Above all, they demanded commitment and dedication from their best players — and so the 1973 Soviet Championship turned out to be one of the strongest Soviet championships ever. Almost everyone who was anyone in Soviet chess took part.

Spassky was sanctioned after his defeat against Fischer. He was not allowed to travel abroad after the competition, despite having received numerous invitations to play attractive international tournaments. These sanctions, as Spassky later explained, led to a crisis — but he seemed to have overcome it at the 1973 Soviet Championships. Spassky won the championship with an 11½ out of 17 score, with Karpov, Petrosian, Polugaevsky, Korchnoi and Gennady Kuzmin trailing a full point behind. In this tournament, Spassky also collected brilliant victories against the Sicilian in important games:

Such games demonstrate the fact that Spassky continued to be one of the strongest players in the world even after his defeat against Fischer. But he never got to play another World Championship match. In 1974 he lost 4-7 to Karpov in the semifinals of the Candidates Tournament; in 1977 he lost 7½-10½ to Korchnoi in the final of the Candidates, in a match in which both sides outdid each other with bizarre behaviour; and in 1980 he was eliminated by Lajos Portisch already in the quarterfinals of the same event — albeit by the narrowest of margins. The match ended in a 7-7 draw after 14 games, but since Portisch had won more games with Black, he was declared the winner.

In 1985, 29 years after his debut in Amsterdam in 1956, Spassky took part in the Candidates Tournament once more in Montpellier and finished in sixth place. After that, Spassky no longer qualified for the Candidates competitions.

However, he remained a welcome guest at numerous top tournaments and team competitions. But by then Spassky lacked the great ambition which propelled him to immense success earlier in his career, and was often satisfied with a quick draw. When he wanted to play, though, he still managed to play beautiful games — even against the Sicilian.

At the 2005 Unzicker Gala in Mainz, Spassky scored a prestigious victory against the Sicilian, as he defeated an old rival of his: Viktor Korchnoi.

Like Spassky, Korchnoi was born in Leningrad (though six years earlier, on 23 March 1931), so the two had been rivals during their childhood and early youth years.

Viktor Korchnoi at the 1985 Hoogovens Tournament | Photo: Rob Croes / Anefo

They faced each other for the first time in 1948 in Leningrad, and their last encounter was played in December 2009, in a 6-game match which took place in Elista. Spassky won the match by a 3½-2½ score (+2 =3 -1).

Graying with honour: Boris Spassky | Photo: Dagobert Kohlmeyer

In total, the ChessBase Mega Database contains 290 games (not counting simultaneous exhibitions) with 1.e4 c5 in which Spassky had the white pieces. Spassky won 122 of these games, 145 ended in draws, and 23 times he suffered a defeat. An impressive record. If you replay even only a few of the best games in this collection, you might get to feel the magic of chess which captivated Spassky as a 9-year-old.