“Simpson’s Divan was naturally the first resort of the incomparable Paul Morphy, and he greatly preferred it to any other chess room he saw, he even went so far as to say it was ‘very nice,’ which was a great deal from him, the most undemonstrative young man we ever met with. Certainly nothing else in London [...] elicited such praise from him as ‘very nice,’ at least as applied to any inanimate object.”

Chess History and Reminisces – H. E. Bird (1893)

When we think today of coffee houses, it is most likely ubiquitous American chains that come to mind. Places which have their uses, but little by way of soul, and no particular connection with chess. Yet, as L. P. Hartley wrote in The Go Between, “The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” I wanted to explore the London of the 18th and 19th centuries, when coffee houses were at the epicentre of the chess world.

These were the venues where players met and reputations were formed. Overseas stars would make their entrance and make their mark. For some, the camaraderie was key, for others, the coffee houses were a place of work. Many books were written by members of the various clubs, and these were sometimes only available exclusively within the coffee houses. Inevitably there were fall outs, and even back then, chess players had to struggle against venues moving them into less favourable spaces, to make way for more lucrative trade.

There certainly was not a flat white or a frappuccino in sight. As Lionel Kieseritzky wrote in 1846 in the Berlin magazine Schachzeitung regarding Simpson’s: “Every visitor must otherwise, on entering the shop through which the staircase leads to the hall, pay a shilling for which he receives a cigar and a card for which he receives upstairs a cup of coffee or tea or a lemonade in exchange.”

There are too many famous coffee houses to do them all justice within a single article. These include Gliddon’s Divan, which Staunton attended in the early 1840s and is noted by Hooper and Whyld in The Oxford Companion to Chess as being “like an Eastern tent, the drapery festooned up around you, and the views exhibited on all sides of mosques, and minarets, and palaces rising out of the water.”

23rd February 1794 at Parsloe’s saw chess played in the presence of the Turkish Ambassador

There was also Parsloe’s on St James’s Street, where Philidor lectured every year. H. J. R. Murray wrote in A Short History of Chess: “At first all the leaders of society belonged to the club, but the fashionable world slipped away and before 1790 only the chess players were left.” H. E. Bird also reminisced thus about the Garrick: “About the year 1840 the Garrick Chess Divan was opened by Mr Huttman at No.4 Little Russell St., Covent Garden. One of the attractions of this little saloon was the publication every week of a leaf containing a good chess problem, below it all the gossip of the chess world in small type.”

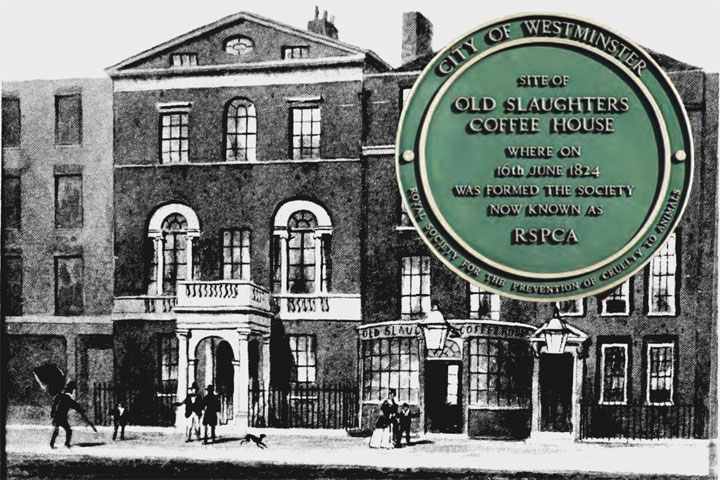

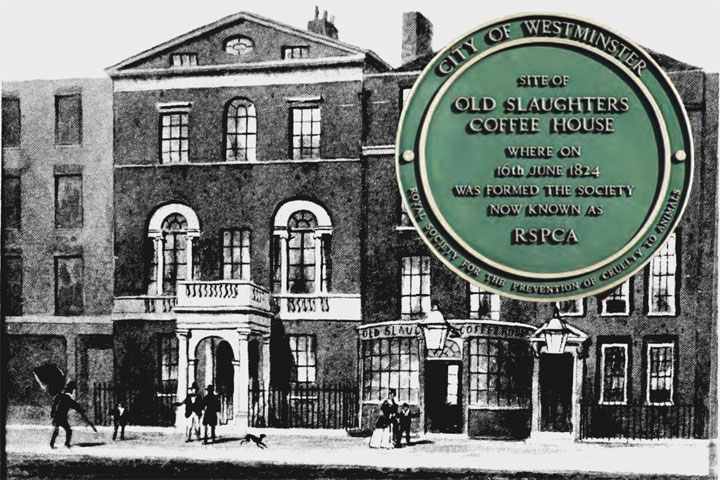

Yet I wanted to focus this piece on two other coffee houses. Kenneth Matthews wrote in British Chess that “The headquarters of British chess in the eighteenth century were first at ‘Slaughter’s Coffee House’ in St Martin’s Lane, London”, while H.E Bird observes in his book, which is in many ways as much a homage to Simpson’s as it is to chess: “The chess events, anecdotes and reminiscences of Simpson’s must ever form a most interesting chapter in the English or National history of chess for the Nineteenth century, and is intimately linked with that of the whole chess world.” So it is these two institutions (one still standing, one long gone) which bridge the 18th and 19th centuries, to which we turn in more detail.

Peter Doggers writes in The Chess Revolution that “In London, you had the Old Slaughter House in St Martin’s Lane, which opened in 1692 and was visited by architects, painters, poets and politicians.” In its day, it was known at different times as Slaughter’s, The Coffee House on the Pavement, The Old Slaughter House and The New Slaughter House. Samuel Johnson, Thomas Gainsborough, and Henry Fielding were all amongst the regulars, and the RSPCA was also founded there.

Nathan Divinsky notes in The Batsford Chess Enclopedia that a private room was set aside for chess, and “From 1700 to 1770 many leading English players congregated there [...] Among the more famous were Cunningham, Stamma and the mathematician De Moivre who according to H. J. R. Murray, ‘lived for nearly thirty years on the petty sums he made at Slaughter’s by chess.’”

Murray himself observed that “The opening of coffee-houses in the closing years of the seventeenth century led to a more public playing of chess and raised the level of play.” He also noted that “Two significant works [were] published by this circle [at Slaughter’s]. In 1735 Capt. Bertin published his Noble Games of Chess, ‘sold only at Slaughter’s Coffee-house’ and Stamma’s 1737 Essai sur le Jeu des Echecs, a collection of 100 endgames, in Paris.” A revised edition including the openings was subsequently published in 1745.

Slaughter’s even inspired the celebrated poet Joseph Thurston to write the following chess-themed poem in 1729.

“Bravely they press to conquer, or to die;

Nor ever was it known a Pawn should fly:

Like sons of Lilliput, so small, so bold,

As we believe and Gulliver has told.

Their Laws, their Orders, and their Manners these;

The rest let Slaughter’s tell you, if you believe.”

Kenneth Matthews writes that “In 1747, the gentlemen of ‘Slaughter’s’ put up their man, Philip Stamma a Syrian employed by the English Government as an interpreter of Oriental languages, to play a match with Andre Philidor, a French musical composer and the greatest chess player of his generation. The Frenchman won easily, by 8 games to 1.” Anne Sunnucks suggests in The Encyclopaedia of Chess that it was even easier than that, as it appears Philidor was also “Giving his opponent odds of the move and allowing him to count drawn games as won.”

Matthews’ writing also shows us that chess variants have clearly been with us for a long time, and it is easy to imagine club members having a lot of fun with them. “After the match, Philidor tried his hand at ‘the Duke of Rutland’s chess’, a comic variant of the game, in which the King stood with the Queen on one side of him, and a new piece, the Concubine (uniting the powers of Rook and Knight), on the other.”

No trace of the building now remains, as it was demolished in 1843 when Cranbourn Street was created, but its legacy lives on.

A contemporary drawing of an 18th century coffee house - Café Manoury in Paris.

Tim Harding writes in Steinitz in London that “From the 1840s to the mid-1860s there was probably no leading chess player in London – or even a middling or weak one – who did not at some time frequent Simpson’s. For some it was their second home, and for the professionals it was their workplace.” He quotes MacDonnell as saying “The Grand Divan in the Strand has, with one or two brief intervals, been the most celebrated chess rendezvous in the world”, as well as Captain Kennedy who described it as “the very headquarters of Metropolitan chess.”

Besides the chess players, other clientele included Benjamin Disraeli, William Gladstone and Charles Dickens. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle also dined there, as did his famous characters Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson, who refer to it from time to time, including in The Adventures of the Dying Detective, where Holmes suggests “Something nutritious at Simpson’s would not be out of place.”

Yet the praise of MacDonnell and Kennedy, and the inspiration Simpson’s might have been to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is as nothing compared to the love that H. E. Bird had for the place. Bird, who is best remembered today for 1 f4, was one of the leading players of his age. Tony Cullen notes in Chess Rivals of the 19th Century: “Neither the grandness of the occasion nor the reputation of his opponent would deter him from playing in his own inimitable style. Henry Bird was a free spirit who went his own way, not wishing to follow the rest down some well-worn theoretical path.”

Bird’s BCM obituary in 1908 gives a real window into his experiences at Simpson’s and of the place itself. “[Bird] was a frequenter of ‘Simpson’s’ Divan at the age of sixteen. The Divan Bird went to was an altogether different Divan from that of later years. Its very name was not Simpson’s, but Ries’. It was much more of a real Divan and much less of a restaurant. It was then almost sacred to the three C’s. – coffee, cigars and chess. One had not then to go up the little old staircase to the second floor to find the chess players [...] What a company, too, Bird met in those early days.” From Staunton, to Buckle, Captain Evans, Captain Kennedy, Horwitz and later Steinitz, they were an illustrious crew.

As Bird put it in his own words, “[Simpson’s] was soon found to afford the most admirable facilities for the quiet and comfortable enjoyment of chess, and hence became greatly appreciated and prominently patronised, and has always been regarded by the best and most impartial friends of chess with sentiments of extraordinary partiality.” Bird was even moved to poetry, which showed that like Slaughter’s, Simpson’s really captured the imagination of its members.

“For Clubs may come, and Clubs may go,

And make us ask what’s next to see;

But Simpson’s ever should remain,

The place for Chess in ecstasy.”

In many ways, Simpson’s was the crucible in which modern chess was born. Bird notes that “It was here that H. T. Buckle, the writer and author, in 1849 gained leading honours in the first tournament ever held on British soil, or so far as is known, on any soil.”

Steinitz after his arrival in 1862 became a “tolerably regular attendant at ‘Simpson’s’ and it was through this that his appointment of Chess Editor to The Field arose.” A vehicle Steinitz utilised to do so much significant writing.

As with the visiting Paul Morphy, Bird was quick to note how much Steinitz also admired Simpson’s. Although, while it does seem likely that Steinitz might have been more effusive than the monosyllabic American, the extent to which Bird attributed his own views on the subject of Simpson’s to Steinitz, might be a matter of conjecture. “Steinitz admits that his pre-eminency in chess is greatly due to the facilities of Simpson’s, and the courtesies of his early opponents. The luxurious couches, tables and mirrors with the splendid light afforded, tempted many visitors who had played not chess, to resort there for pleasing converse, combined with ease and comfort, and a record of the distinguished men which have been seen in the Divan would make a distinguished list.”

As ever with Steinitz, his interactions at Simpson’s were not entirely straightforward. At one point, following a convoluted dispute with Patrick Duffy, he was banned from attending for several weeks, and while he returned, this ultimately sowed the seeds for him leaving London altogether and caused schisms in Simpson’s which were never fully healed.

It should be noted that Steinitz was by no means the only player for whom Simpson’s led to opportunities to make money. Harding observes that in terms of wagers, “One shilling, twice the value of a sixpence, was noted by several writers as the usual rate at Simpson’s, whereas sixpence was probably more customary among less affluent players.” Harding also cites evidence that the attitudes of players towards wagers could vary at different stages of their lives, depending on how affluent they happened to be. “Though Staunton professed to despise those who played for money, one of the professionals said ‘I knew him when he was glad to play for threepence a game.’”

While for some, such as the sixteen-year-old Bird, Simpson’s could be associated with the beginning of their chess life, for others it marked the end. La Bourdonnais and MacDonnell had played what many consider to be the first unofficial world chess championship match at the Westminster Chess Club. La Bourdonnais subsequently took up the position of chess professional at Simpson’s, but as Divinsky notes, he died soon afterwards. The 1878 Chess Player’s Chronicle obituary of John Cochrane notes that he died at St George’s Chess Club “only two days before his death: and on the Wednesday, as we learn from Mr. Steinitz in the Field, he had called at [Simpson’s] and left a note for that gentleman, evincing his usual keen interest in all matters of Chess.”

Zukertort went one better by dying after a game at Simpson’s. Bird lamented that “By the sudden death of Mr Zukertort, last Wednesday morning, the royal game of chess loses one of its most interesting and brilliant exponents. This distinguished master was only forty-six, and he has been cut off right in the middle of an interesting tournament at the British Chess Club, in which he stood the best chance of winning the first prize. Amongst his last conversations was arranging to play Blackburne on Sunday, and Bird on Monday.”

Yet ultimately the demise of Simpson’s as a chess playing centre was not caused by the loss of any of its patrons, sad though their passing undoubtedly was, but more through the changes that came about in the venue itself. MacDonnell wrote in Life-Pictures in 1866: “The chess players were relegated to a higher region and less commodious room. In consequence of this change most of the leading frequenters abandoned Simpson’s altogether and formed the Westminster Club, which at once attracted and for six years retained the largest company of distinguished chess-players enrolled in any society.”

George Walker wrote in 1870 that the Divan was “once a good and well-ventilated room. It is now a dog-hole and nothing better.” A very sorry state of affairs, and a world away from the effusive praise Bird had once been able to lavish. MacDonnell highlighted that some members did return to Simpson’s “and essayed to revive its ancient glories. For a time they achieved a partial success, but the fates were against them. The smallness of the room, always a source of discomfort, coupled with the circumstances of a painful nature that happened about five years ago [the Steinitz-Duffy dispute], compelled them to desist from their efforts, and either to abandon wholly their once-beloved haunt, or only to favour it with angels’ visits. But still the Divan is not wholly wanting in attractions for the ardent votary of Caissa [...] There Steinitz oft paces up and down the chuckling over his own pretty jokes, or retelling his myriad grievances.”

So it was that Simpson’s declined in importance. Now it is simply a restaurant, not all that far from where I work. A chess board that is said to have been used by Staunton, Morphy, Steinitz and Lasker is still on show in the foyer, echoes of a past long gone.

Slaughter’s and Simpson’s both played a crucial role in the development of our game. They were places of creativity, camaraderie and doubtless great fun, in which competitive chess was formalised and from which the modern tournament era emerged. We should note too that they were far from perfect. They were aristocratic, especially in the 18th century, and it does not take a particularly eagle-eyed reader to spot that all the described participants were men. Yet these institutions played a crucial part in taking chess forward.

Bird would not get his wish “But Simpson’s ever should remain, The place for Chess in ecstasy,” yet it would be nice to think that were he able to witness today’s chess scene, he would know that Simpson’s and his time in it had played their part. As had Slaughter’s before it. Of the “three C’s”, cigars may be less prevalent in today’s society – but chess and coffee are as integral now as they ever were.

Ben Graff is a man with a very rich biography and an impressive and inspiring life story. He describes himself primarily as a writer and chess journalist – he has written two books (one chess-related and one non-chess related) and has been a regular contributor to Chess Magazine, he writes for The Chess Circuit and The Gazette (The Blind Chess Association Magazine) and also for Authors Publish and a number of other publications.

Ben Graff is a man with a very rich biography and an impressive and inspiring life story. He describes himself primarily as a writer and chess journalist – he has written two books (one chess-related and one non-chess related) and has been a regular contributor to Chess Magazine, he writes for The Chess Circuit and The Gazette (The Blind Chess Association Magazine) and also for Authors Publish and a number of other publications.

The above feature is reproduced from Chess Magazine March/2025, with kind permission.

CHESS Magazine was established in 1935 by B.H. Wood who ran it for over fifty years. It is published each month by the London Chess Centre and is edited by IM Richard Palliser and Matt Read.

The Executive Editor is Malcolm Pein, who organises the London Chess Classic.

CHESS is mailed to subscribers in over 50 countries. You can subscribe from Europe and Asia at a specially discounted rate for first timers, or subscribe from North America.

| Advertising |