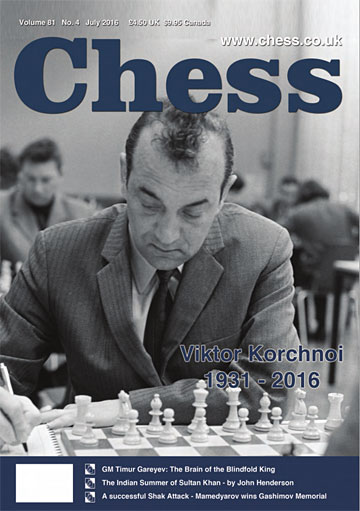

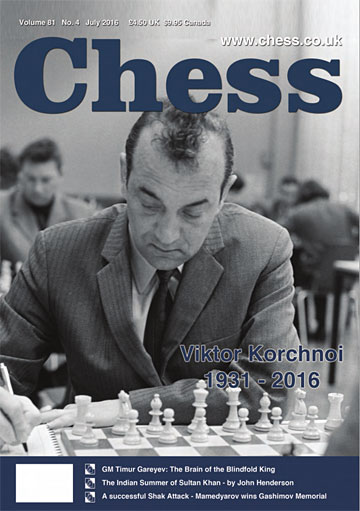

Viktor Korchnoi, 1931 – 2016

By Jonathan Speelman

The death last month of the great Viktor Korchnoi marked the end of an era and of a super-grandmaster who was one of a kind. In 1953, the young Korchnoi twice played Grigory Levenfish, making a win and a loss apiece – Levenfish was born in 1889. Fully five decades later, Korchnoi played and defeated the 14-year-old Magnus Carlsen at a tournament in Norway in 2004. Overall he did battle by his own reckoning with six generations of chess players!

Victor Lvovich Korchnoi was born in the then Leningrad on March 23rd 1931 to a Jewish father and a Catholic mother. His father taught him chess at the age of five, he joined the local Pioneers Palace in 1943, and by 1947 he had already won he USSR Junior Championship with a massive score.

But the defining events of his youth were the horrors of the years under Stalin preceding the war and, above all, the 872-day Siege of Leningrad. With his parents divorced, his father dead after one of the early battles of the war, and his grandmother and her brother, whom he helped to bury, both gone, Korchnoi survived it with his stepmother of whom he was clearly very fond as the first chapter of Chess is My Life shows.

After the terrible privations of his childhood, Korchnoi was always a difficult man, but he used it to become one of the (arguably the) strongest chess players ever not to become world champion: with a lifelong devotion to chess and a unique career.

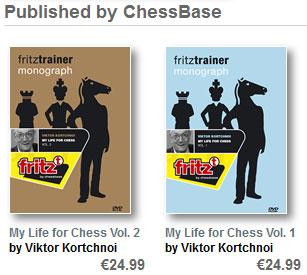

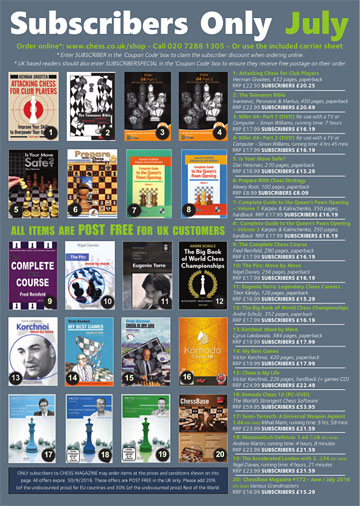

In the weeks since Korchnoi’s death the details of that career have been rehearsed endlessly elsewhere, but I will briefly summarise. Korchnoi began his international chess career in the 1950s with his first tournament abroad in Bucharest 1954 where he was first ahead of Rashid Nezhmetdinov (and Bob Wade was somewhere near the bottom). At that time, the USSR Championship was the world’s strongest annual event and Korchnoi had already made his debut at the end of 1952 when he was sixth and been second in the following championship (there wasn’t one in 1953), at the very beginning of 1954. He went on to compete many times and won four in Leningrad 1960, Yerevan 1962, Kiev 1964-65 and Riga 1970.

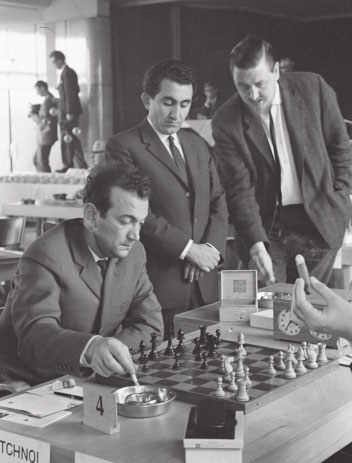

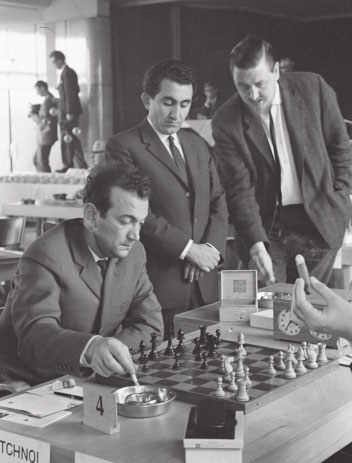

Korchnoi playing for the USSR against the Netherlands, The Hague, 1962.

The two interested spectators are the soon-to-be world champion,

Tigran Petrosian, and the top Dutch player, the GM Jan Hein Donner.

Despite these huge successes, numerous further victories in international tournaments and successful appearances for the USSR in the Olympiad and the European Team Championship, Korchnoi was never considered fully ‘reliable’ by the Soviet authorities and in the early to mid 1970s found it almost impossible to travel abroad.

In 1976, however, he was allowed to play in a tournament in Amsterdam and after sharing first place with Tony Miles, asked Miles at the closing ceremony how to spell ‘political asylum’. He defected to the West, living first in Holland, then Germany, and from 1978, Switzerland. His wife Bella and son Igor were eventually also able to leave the Soviet Union, though only after Igor had served two and a half years in a labour camp for ‘evading military service’. However, Korchnoi subsequently divorced and married Petra Leeuwerik who was with him till the end.

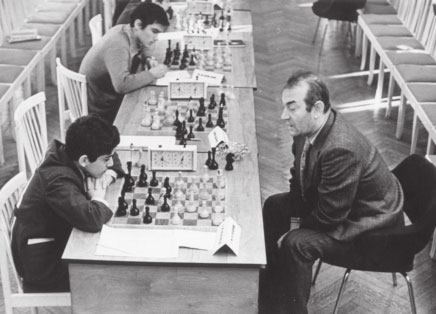

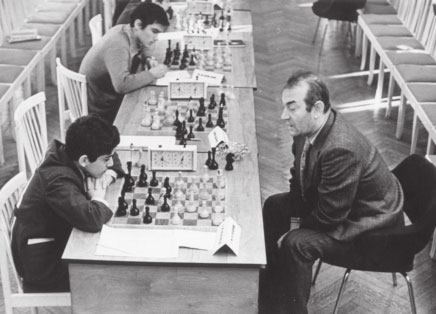

Taking on a young Garry Kasparov in a clock simul held in Viktor’s hometown of Leningrad

in 1975. This game, the first of many between Korchnoi and Kasparov, ended in a draw.

Korchnoi’s defection led after he defeated Boris Spassky in the final of the Candidates cycle in 1977 to one of the hardest fought and bitterest matches of all time both on and off the board: the world championship against Anatoly Karpov in Baguio City in the Philippines in 1978. Karpov’s team included Dr. Zukhar, a well-known hypnotist and ‘parapsychologist’, whose presence in the audience greatly worried Korchnoi, who had him sent back several rows, and no fewer than 17 KGB agents! Korchnoi countered with two members of an Indian religious sect, the Ananda Marga, then on bail for murder.

On the board, Karpov took an early lead, but Korchnoi fought back wonderfully winning three out of four consecutive games to equalise before Karpov got him in the decisive 32nd game. They also played a second world championship match in Merano 1981, but it was much so one-sided that it’s sometimes been termed the ‘massacre in Merano’.

|

Viktor takes a break for a spot of table tennis during the 30th Hoogovens Chess Tournament held in Wijk aan Zee, January 1968. After an amazing run of ten wins from his first eleven games, Korchnoi was the runaway winner, some three points ahead of Portisch, Tal and Hort. |

Ray Keene and Michael Stean were Korchnoi’s seconds in Baguio and I also briefly occupied that position. It happened at the 1985 Montpellier Candidates tournament, which I went to as first reserve. When nobody had the good grace to fail to appear or fall sufficiently ill, I worked for Victor for several rounds. But disappointed not to be playing myself, I doubt I was much use and he soon fired me, though we maintained perfectly reasonable relations thereafter.

I first played Victor in the Phillips and Drew Kings tournament in London 1980 – a draw – and went on to face him about 18 times in total with a smallish but respectable minus score. He was famous, of course, for the tirades he would unleash after losing – some I later learned apparently rehearsed in advance depending on the result! – but I don’t remember anything exceptional the few times I did win.

In any case ‘Viktor the Terrible’ needed fury to play his best. Sometimes, as against Karpov, it was surely real, but other times more artificial. And I would urge readers who haven’t seen it before to watch his wonderful self parody in an advertisement for the Swiss Milk Marketing Board, in which he starred opposite Lovely the cow. After a sequence of agonised facial expressions, he resigns dramatically to a screaming chord and storms from the board to the message “Milk works wonders each and every day”. She swishes her tail, turns to the ecstatic audience and appears to wink.

Korchnoi actually effectively played three world championship matches against Karpov since the final of the Candidates in 1975 produced the next world champion when Bobby Fischer refused to defend his title. Korchnoi never regained the absolute heights after Merano, but he still had a huge part to play when in 1984 he was paired against Garry Kasparov in the Candidates.

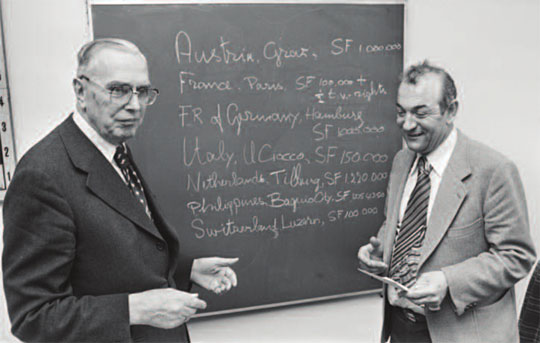

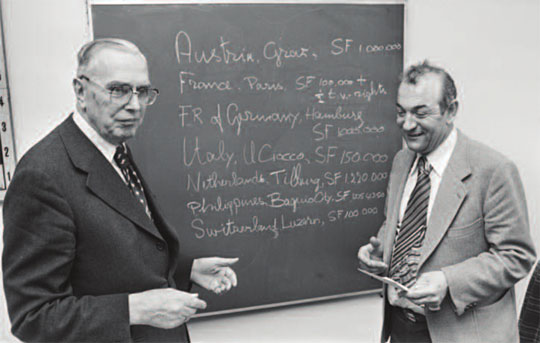

A smiling Viktor pictured in February 1978 with the head of FIDE and former world champion, Max Euwe. Eagle-eyed readers will note the blackboard in the background which shows the bids to host the 1978 World Championship match between Karpov and Korchnoi. Of the seven bids received, Karpov’s first choice was Hamburg as it was “the nearest to Leningrad”, while Korchnoi chose Graz. The Philippine bid of Baguio City was accepted as a compromise.

This match was originally scheduled to be in Pasadena in California, but after fractious negotiations with the Soviet Chess Federation broke down, Korchnoi was declared the winner. Very nobly, he refused to accept this and they later played in London. Korchnoi won the first game, but in the end Kasparov was too strong for him and went on to face Karpov in the first of their many matches, the ‘Moscow Marathon’.

In his later years, Korchnoi softened somewhat and he was an energetic and amusing presence in the VIP room at the first few editions of the London Classic where, with myself and John Nunn as chief sub-barrackers, he punctuated Julian Hodgson’s commentary, reserving particular opprobrium for those who chose to defend the King’s Indian. He loved the space advantage that White gets in such lines and aimed for total control. In defence he was a lion (living up to his name of ‘lion’s son’), and in the endgame at his best, tremendous.

|

To give a pictoral context to Korchnoi’s longevity at the top of the chess ladder, here is a picture of a smiling Viktor (pictured second from right on the first row) from Kiev in 1954 where he was playing in his second USSR Championship. In this typically hugely strong event, Korchnoi finished tied for second with Mark Taimanov, a point and a half behind Yuri Averbakh, who is pictured to Viktor’s left.

And at the other extreme, here is Viktor in Gibraltar in 2011 nearly sixty years later about to do battle with Fabiano Caruana. Korchnoi was Black and was giving away nearly 200 Elo points to the young pretender, but won in 46 moves for surely the shock of the tournament. The quote attributed to Wilhem Steinitz seems particularly apt about this and many of Viktor’s later games: “I may be an old lion, but I can still bite someone's hand off if he puts it in my mouth.”

|

Playing chess was Victor’s life and at the age of 79 he ventured forth in London from the VIP room to face the public in a simultaneous display which lasted more than five hours. Wheelchair-bound at the beginning of last year, he nevertheless played a four-game rapidplay match against Wolfgang Uhlmann in Zurich which they drew 2-2, and when he was invited back to Zurich at the beginning of this year, he complained when they only wanted him as a guest of honour rather than in battle. He was a truly great warrior.

I’ve chosen a crucial and beautifully played endgame to finish. It comes from what turned out to be the penultimate game in Baguio, as Korchnoi, who had trailed 2-5 in the race to six wins, hauled himself back to 5-5 only to lose everything in game 32.

To help me, I dug our Ray Keene’s book of the match, and apart from concentrating on this game, reread the introduction and the appendix at the end with selected documents. These comprise Korchnoi’s open letter to President Brezhnev requesting that his family to be allowed to leave the Soviet Union and then a succession of protests from the two camps during the match. They brought back sharply the vitriol of the proceedings and the extreme level of enmity at the time.

[Event "World Championship, Baguio City"] [Site "?"] [Date "1978.??.??"] [Round "31"] [White "Korchnoi, V."] [Black "Karpov, A."] [Result "1-0"] [ECO "D36"] [Annotator "Jon Speelman"] [PlyCount "141"] [EventDate "1978.??.??"] [SourceTitle "Chess 2016 #07"] [SourceDate "2016.06.23"] 1. c4 e6 2. Nc3 d5 3. d4 Nf6 4. cxd5 exd5 5. Bg5 Be7 6. e3 O-O 7. Bd3 Nbd7 8. Nf3 Re8 9. Qc2 c6 10. O-O Nf8 11. Bxf6 {This allows White to start the minority attack immediately.} ({Instead,} 11. h3 {, as Karpov subsequently played a number of times, is most common nowadays;}) ({while White has also often gone} 11. Rab1) ({and at least a dozen other moves, most notably} 11. Rae1 {which leads to} Ne4 12. Bxe7 Qxe7 13. Bxe4 dxe4 14. Nd2 f5 15. f3 exf3 16. Nxf3 Be6 {.}) 11... Bxf6 12. b4 Bg4 13. Nd2 Rc8 (13... Bh5) 14. Bf5 Bxf5 15. Qxf5 Qd7 16. Qxd7 Nxd7 17. a4 Be7 18. Rfb1 Nf6 19. a5 {Allowing the queenside to be blocked, but in return White gets a stable square on c5 for his knight and can slowly play towards e4, mobilising his centre.} a6 20. Na4 Bf8 21. Nc5 Re7 22. Kf1 Ne8 23. Ke2 Nd6 24. Kd3 Rce8 25. Re1 g6 {Keene writes: "Hereabouts the Russians, Tal, Vasiukov, Zaitsev, etc were claiming an advantage for Black. Euwe was very scathing about this and took great delight in making his point by repeatedly slaughtering Baturinsky from this position in the press room."} 26. Re2 f6 (26... f5 {would have weakened e5, but forced White to exchange if he wants to get in e4.}) 27. Rae1 Bh6 28. Ndb3 Bf8 29. Nd2 Bh6 30. h3 Kf7 31. g4 Bf8 32. f3 Rd8 33. Ndb3 Nb5 34. Rf1 Bh6 35. f4 Bf8 36. Nd2 Nd6 37. Rfe1 h6 38. Rf1 Rb8 39. Ra1 Rbe8 40. Rae1 Rb8 41. e4 {Korchnoi had waited until after the time control before making his break.} dxe4+ 42. Ndxe4 Nb5 43. Nc3 Rxe2 44. Rxe2 Bxc5 {Having passed move 40, Karpov could have adjourned at any point, but he carried on, making a natural-looking if committal exchange.} 45. bxc5 Rd8 46. Nxb5 axb5 47. f5 {Karpov now decided to adjourn, taking twenty minutes on his sealed move. Although the white pawns on d4 and especially a5 are vulnerable, the most important point here is that White has space with his pawns further advanced. This means that in the event of a race he should be ahead and there is also the prospect of sacrificing pawn(s) to get the king in. It presumably ought to be defensible for Black, but was most unpleasant for Karpov.} gxf5 48. gxf5 Rg8 ({If} 48... Re8 {not} 49. d5 $2 ({Korchnoi intended} 49. Ra2) 49... Rd8 $1 (49... Rxe2 $4 50. Kxe2 { and then} Ke7 ({or} 50... cxd5 51. c6) 51. dxc6 bxc6 52. a6 {wins}) 50. d6 Re8 {, which is drawn because} 51. Rxe8 ({if} 51. Ra2 Re5 {, the rook is much too active and White should admit his error with} 52. Re2 $1) 51... Kxe8 {is completely dead.}) 49. Kc3 Re8 ({If, instead,} 49... Rg1 {, Korchnoi intended} 50. a6 bxa6 51. Re6 a5 52. Rxc6 Rg3+ 53. Kd2 {with a race which would be incredibly hard to calculate accurately. They must have had quite a night of it looking at lines like this, but nowadays with computer assistance it would be possible to come to a clear verdict with enough effort. Given that Black was actually OK until several moves further on Karpov's decision was fine.}) 50. Rd2 Re4 ({Keene says that they had not considered this and thought that} 50... Re1 {was stronger, but} 51. d5 Rc1+ {is what they were concerned about, but after} (51... cxd5 52. Rb2 Rc1+ 53. Kb4 {is most unpleasant: for example:} Ke7 (53... d4 54. Kxb5 d3 55. Rd2 Rb1+ 56. Kc4 Rc1+ 57. Kd5 Ke7 ({not} 57... Rc3 $2 58. Kd4) 58. Rxd3 Kd7 {is a better defence, but still very grim}) 54. Kxb5 Kd7 55. Kb6 Kc8 56. a6 bxa6 57. c6 d4 58. Rg2 Rb1+ 59. Kc5 d3 60. Kd6 Kb8 61. c7+ Kb7 62. Kd7 {wins.}) 52. Kb2 $1 ({not} 52. Rc2 Ra1 $1) 52... Rxc5 53. dxc6 Rxc6 54. Rd7+ Kf8 55. Rxb7 Ra6 56. Rxb5 Ke8 57. Rd5 {, White has very good winning chances.}) 51. Kb4 Ke8 52. a6 bxa6 53. Ka5 Kd7 54. Kb6 b4 55. d5 cxd5 56. Rxd5+ ({Certainly not} 56. c6+ $2 Kd6 57. c7 Rc4 {.}) 56... Kc8 57. Rd3 a5 $2 ({The first impression of a position like this is that Black should simply be lost. However, the b-pawn is advancing and it seems that Karpov still had a perfectly adequate defence with} 57... Rc4 $1 {, impeding the c-pawn's advance from behind:} 58. c6 (58. Rg3 Rc3 59. Rg8+ Kd7 60. Rg7+ Ke8 61. Rb7 b3 62. Kc6 a5 {is okay}) 58... Rc3 59. Rd2 (59. Rd7 b3 60. Ra7 Kd8) 59... b3 60. Rg2 Rd3 61. Rg8+ Rd8 62. Rg7 b2 {and White must take the draw.}) 58. Rg3 b3 $2 {A panicky move after which White's advantage is obvious.} (58... Rd4 {was correct first, because if} 59. c6 b3 {the king can't now hide on c6 and White must play} 60. Rg8+ ({and not, of course,} 60. Rxb3 $4 Rb4+) 60... Rd8 61. Rg7 {, which should lead to a draw.}) 59. Kc6 $1 Kb8 (59... Rd4 60. Rxb3 a4 61. Rg3 Kb8 62. Ra3 Kc8 63. Kb5 Rf4 64. Rxa4 Rxf5 65. Kc6 {also looks lost.}) 60. Rxb3+ Ka7 61. Rb7+ Ka6 62. Rb6+ Ka7 63. Kb5 {Now White is completely winning.} a4 64. Rxf6 Rf4 65. Rxh6 a3 66. Ra6+ Kb8 67. Rxa3 Rxf5 68. Rg3 Rf6 69. Rg8+ Kc7 70. Rg7+ Kc8 71. Rh7 1-0

The above article appeared in the July 2016 of the British magazine CHESS

CHESS Magazine was established in 1935 by B.H. Wood who ran it for over fifty years. It is published each month by the London Chess Centre and is edited by IM Richard Palliser and Matt Read. The Executive Editor is Malcolm Pein, who organises the London Chess Classic.

CHESS is mailed to subscribers in over 50 countries. You can subscribe from Europe and Asia

at a specially discounted rate for first timers here, or from North America here.

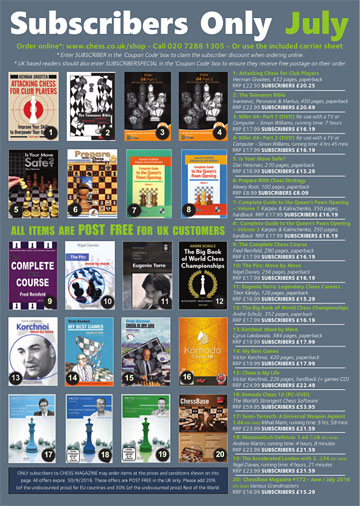

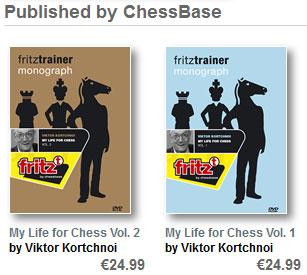

Viktor Korchnoi Viktor Korchnoi

born 1931, two-times contender for the world championship, is a piece of living chess history. In the 60 years of his career, "Viktor the Terrible" crossed swords with practically all great players of the past and presence, including Bobby Fischer and Garry Kasparov. A relentless fighter at the board, he expressed his never-ending love for the royal game in a very simple phrase - "Chess is my life".

In 2005, at the age of 73, Viktor visited ChessBase in Hamburg, to record two fascinating DVDs on a life devoted to chess – a career that spanned more than five decades and six generations of opponents. Kortchnoi was never one to mince his words. On these DVDs he created a vivid memorial to himself and his great chess career. In Volume 1, he presents eight of his most brilliant effort from the years 1949-1979, describing in detail the story around each game, never beating around the bush, sometimes harshly criticizing his opponents, but also lavishing praise on them when this is warranted. A highlight is the game against Karpov from the match for the world championship in Baguio 1978.

“My Life for Chess Vol. 1” offers more than three hours of first-class chess training, plus an extensive interview. A must-have for every chess fan! Volume 2 features about four hours of “Kortchnoi live”. The great chess legend presents among other things his games against Kasparov (1986), Spassky (1989) and Short (1990) in his typical gripping style. Embedded in the game commentaries are many details of Kortchnoi’s biography. For instance, before commenting his game against Spassky, the veteran speaks extensively about his personal relationship towards the ex-world champion. Throughout these lectures you can feel Kortchnoi’s ever-enduring love for chess. Whenever the great master gets to the heart of an opening (King’s Indian, English and French) or shows an astonishing move, one can see the joy sparkling from his eyes. No wonder – hardly any other chess genius has lived chess as intensively as “Viktor the Terrible”.

Order these very popular Korchnoi DVDs in the ChessBase Shop

|

Viktor Korchnoi

Viktor Korchnoi