Steinitz as a Player and Thinker

The once well-known chess commentator, IM Vladimir Vuković (today known to most players primarily through his classic The Art of Attack in Chess), expressed the view that Steinitz was the first true chess professional—the first to live entirely from chess. Although this view may be debatable, since there were players before Steinitz who practically lived from the game (Labourdonnais, for example), Vuković likely meant that Steinitz was the first to devote himself completely to chess: playing games, giving simultaneous displays, playing handicap matches, tournaments, matches, writing about chess, thinking, analyzing… everything needed for the development of chess thought.

Generally speaking, we may say that Steinitz was not only a great player (the first World Champion) but also a great thinker, and that these two components are inseparable. Especially after 1873, while formulating and developing his theory, Steinitz sought to prove it in practice. This was, on the one hand, extraordinary, since by confirming his theory, he produced remarkable games; yet on the other hand, because some of his claims (as in any field of human inquiry) were questionable, disasters occasionally occurred. One example is his telegraph match with Chigorin in 1890, which he lost 2–0.

Steinitz as a Player

When speaking of Steinitz as a player, we may note that he played far more matches than tournaments—likely because they were easier to organize, as sponsors could be found more readily. His match results are astonishing: he won every match except the first one (in 1860 against Jenej), which ended in a draw, and the two World Championship matches he lost to the much younger (and, it must be said, stronger) Emanuel Lasker. Many authors consider him the World Champion from his 1866 match with Anderssen, which he won 8–6 (and let us note that every single game of that match had a decisive result!). Still, the first official World Championship match was played in 1886, against his strongest contemporary rival, Zukertort. Although Steinitz had already played a match against Zukertort in 1872, winning convincingly (+7 -1 =4), the young Zukertort had clearly improved, and the question was: which of the two was truly stronger?

Zukertort vs Steinitz, during their first World Championship match

In the first phase of the match, the struggle was tense and uncertain. However, in the second half, Steinitz completely dominated, so that the identity of the winner was never in doubt: Steinitz won the match quite convincingly (+10 -5 =5), and thus officially became the first World Champion. From that year onward, the title of World Champion is considered formally established, which means that Steinitz was significant also as the founder of the official World Championship. It is worth noting that the Masterclass video course includes all the games of that match, annotated in detail and with great instructional value.

What makes Steinitz great as a personality is the fact that he always played his World Championship matches against the strongest challengers (later, certain champions avoided the toughest opposition… even his successor excelled in doing so). The video course includes all the games from Steinitz’s World Championship matches, most of them annotated. Steinitz, following his usual custom, offered a match to the strongest player of the time, Tarrasch, who declined, citing medical practice. In 1894, the young and still not fully established Emanuel Lasker challenged Steinitz, and Steinitz accepted. The aging champion lost the match, and Lasker became the second World Champion.

All in all, between 1863 and 1894, Steinitz played 27 matches, winning 27 of them. As for his tournament achievements, the most notable results include victory in London 1866, second place in Baden-Baden 1870, first place in Vienna 1873, second place in London 1883 (behind Zukertort), victory in New York 1889, and second place in St. Petersburg 1895 (behind then-champion Lasker).

The Significance of Steinitz for the Development of Chess Thought

From the moment he appeared on the chess scene, Steinitz has remained an intriguing figure—both as a personality and as a great player and thinker. A considerable number of books and articles have been devoted to him, and in recent years several noteworthy titles have appeared. For example, Tim Harding’s Steinitz in London provides a detailed account, accompanied by games, of the period Steinitz spent living in London. Equally interesting is Willy Hendriks’s The Ink War, which explores the clash of ideas between Steinitz and his great rival, Johannes Zukertort.

There is an opinion—today fairly widespread—that studying games of the old masters is essentially a waste of time, and that only modern games should be examined. Without entering a deeper debate, I will simply say that, in my view, it is nearly impossible to attain a profound understanding of chess without a solid knowledge of the classical heritage. (This is similar to the necessity of understanding classical philosophy in order to properly grasp modern philosophical thought.) Kasparov essentially confirmed this by writing his five-volume series on his great predecessors, and in Carlsen’s games, we can clearly see his deep command of classical ideas.

At the foundation of classical chess lies none other than Wilhelm Steinitz (who later changed the spelling of his name to William). Before Steinitz, it was commonly believed that games were won solely by the player’s genius—that, for example, combinations did not inherently exist on the board, but were created by the player. In his early career, Steinitz held a similar view, but after his relatively disappointing result at the 1870 Baden-Baden tournament (where he finished second behind Anderssen, despite being considered the favorite), he analyzed his games as deeply as possible and posed a simple question to himself: Are there certain rules, certain principles that one should follow during a game?

Gradually, he arrived at his own theory (which he modified over the years), and from that moment Steinitz has been regarded—quite justifiably, in my opinion—as the founder of modern chess. He applied his ideas in practical play, though not always successfully, which is normal for any innovator. Perhaps the greatest praise he ever received came from his successor Lasker, who said that Steinitz was “a thinker worthy of a university chair.” And Lasker knew exactly what he was talking about: not only did he defeat Steinitz in their world championship match, but he was also, in his own right, a philosopher and academic.

Wilhelm Steinitz, Father of the Modern School

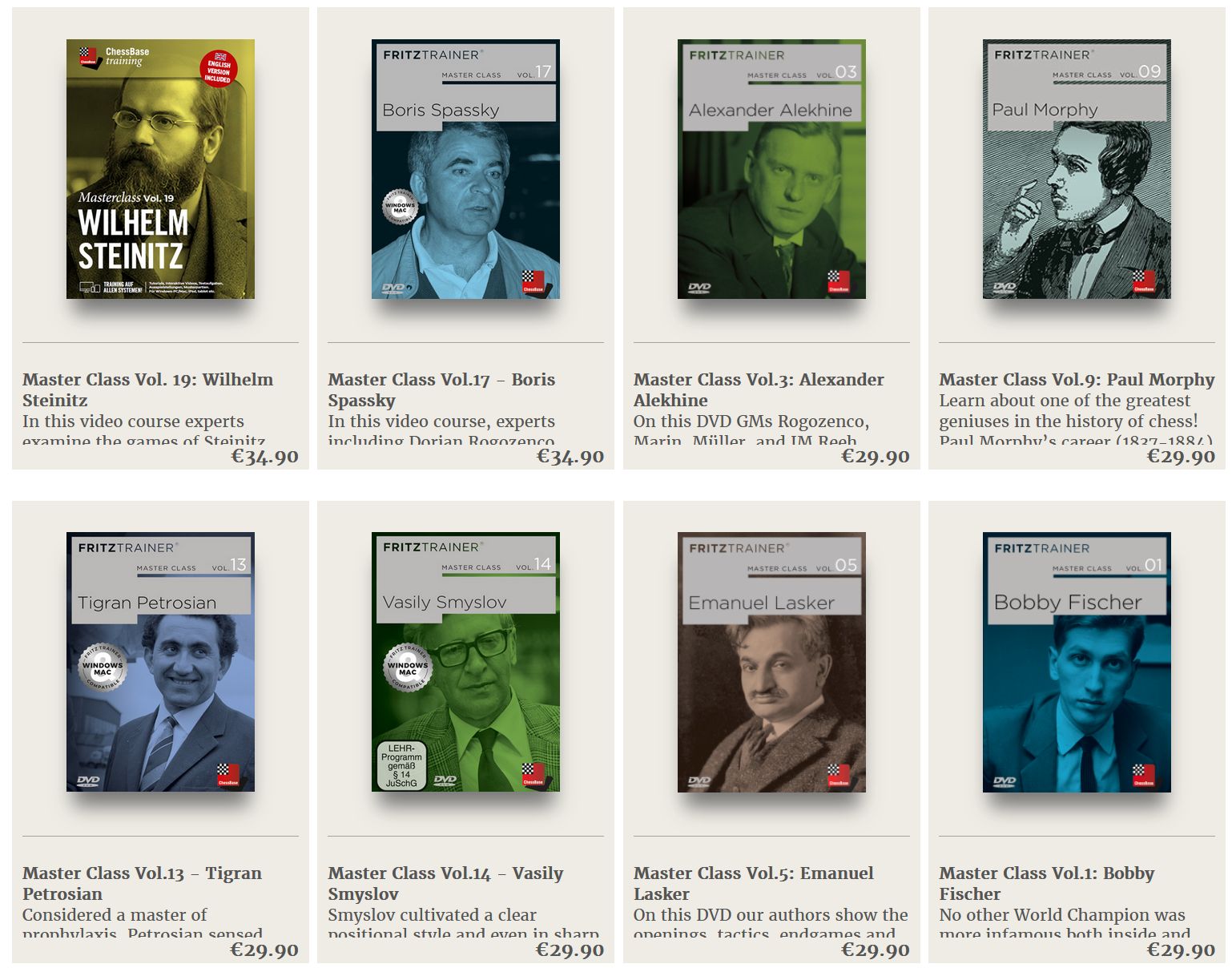

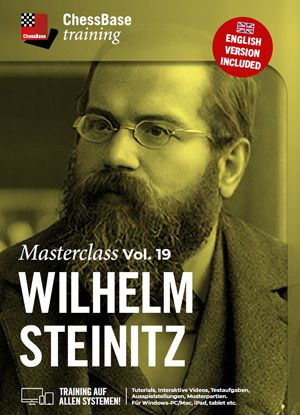

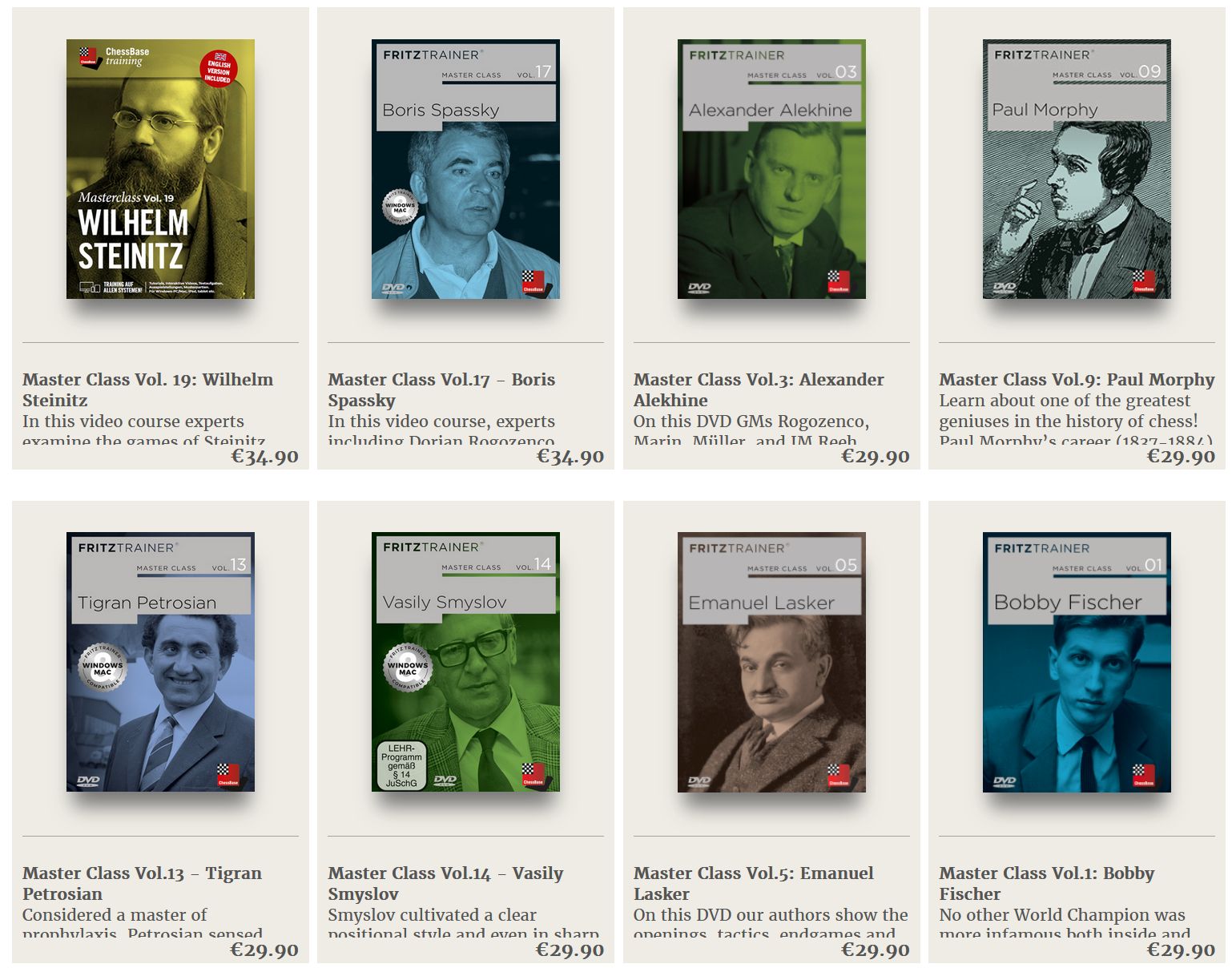

The video course belongs to the Master Class series, which currently includes 18 video courses; this one is the nineteenth in the series. The fundamental idea behind these editions is twofold: on the one hand, to acquaint us with the creative legacy of the great masters through their finest achievements, and on the other, to assist us in achieving a deeper understanding of our game. All ChessBase video courses follow the same structure: a brief biography of the player, his contribution to opening theory, strategy, tactics, and endgames. An important section includes all of the player’s games, some of which are thoroughly annotated. The subject of our text is the latest video course devoted to the first World Champion, Wilhelm (William) Steinitz (1836–1900).

The video course belongs to the Master Class series, which currently includes 18 video courses; this one is the nineteenth in the series. The fundamental idea behind these editions is twofold: on the one hand, to acquaint us with the creative legacy of the great masters through their finest achievements, and on the other, to assist us in achieving a deeper understanding of our game. All ChessBase video courses follow the same structure: a brief biography of the player, his contribution to opening theory, strategy, tactics, and endgames. An important section includes all of the player’s games, some of which are thoroughly annotated. The subject of our text is the latest video course devoted to the first World Champion, Wilhelm (William) Steinitz (1836–1900).

What Can We Expect from This Video Course?

The central theme of this video course, approached from various angles, is as follows: What makes this unquestionably great player and thinker so significant for the development of chess? And equally important: Why is studying Steinitz’s work still necessary today? This guiding idea is the core strength of the course. Many books on Steinitz present his games chronologically—which certainly has its value—but the essential question here is: What exactly makes Steinitz relevant even today? Specialists from various fields—true masters of their craft—offer valuable insights into this.

The course begins with a short biography of Steinitz, sufficient to acquaint the viewer with the essential facts of his life. Those who wish to explore his biography in more depth will, of course, need to consult additional sources.

Steinitz and the Openings - Dorian Rogozenco

Dorian Rogozenco, a well-known authority on openings (as evidenced by his excellent ChessBase DVDs), discusses Steinitz’s influence on the development of several key opening systems. There exists a misconception that even the strongest players of the 19th century had only a rudimentary understanding of opening theory and largely invented their ideas over the board. Rogozenco convincingly refutes this: Steinitz analyzed numerous openings deeply (for his time) and made invaluable contributions that remain relevant today.

Rogozenco highlights Steinitz’s role in the development of the following openings:

-

The King’s Gambit, which was nearly unavoidable in that era.

-

The Evans Gambit, which Steinitz handled with both colors. Although rarely seen today, the opening is unimaginable without Steinitz’s games.

-

The Two Knights Defense, where we can see Fischer—an admirer of Steinitz—applying Steinitz’s ideas as White.

-

The Scotch with 4…Qh4, seldom played today but instructive for understanding how White should pursue an advantage.

-

The Vienna Game – Steinitz’s Gambit with 5.Ke2, important primarily from a historical standpoint. Steinitz famously argued that the king could be a strong piece even in the opening and middlegame. While we now recognize the risks of exposing the king, certain games demonstrate the surprising validity of his theory. (Who can forget the famous Short–Timman game, in which Short’s king marched from g1 to h6 in the middlegame? There is even an entire book devoted to this topic.)

In my view, Steinitz’s greatest contribution to opening theory lies in the Ruy Lopez, where his line with 3…d6 is still played today. For those who believe that old masters played openings poorly, I recommend examining how Steinitz played the French Defense as White. The line 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.e5, which still bears his name, remains the most popular variation in the French today!

All in all, this section offers the viewer many pleasant surprises.

Steinitz and Strategy – Mihai Marin

When it comes to Steinitz and strategy, few are as qualified to speak as GM Mihai Marin, author of the now-classic Learn from the Legends series.

Marin addresses an essential question: Is Steinitz still relevant today, or does he belong to the era of dinosaurs? Using instructive examples, Marin convincingly demonstrates that Steinitz’s legacy demands the deepest study. He begins by showing one of his own games, played quite deliberately—in Steinitz’s style. He then presents two modern games in which Steinitz’s strategic ideas are clearly applied.

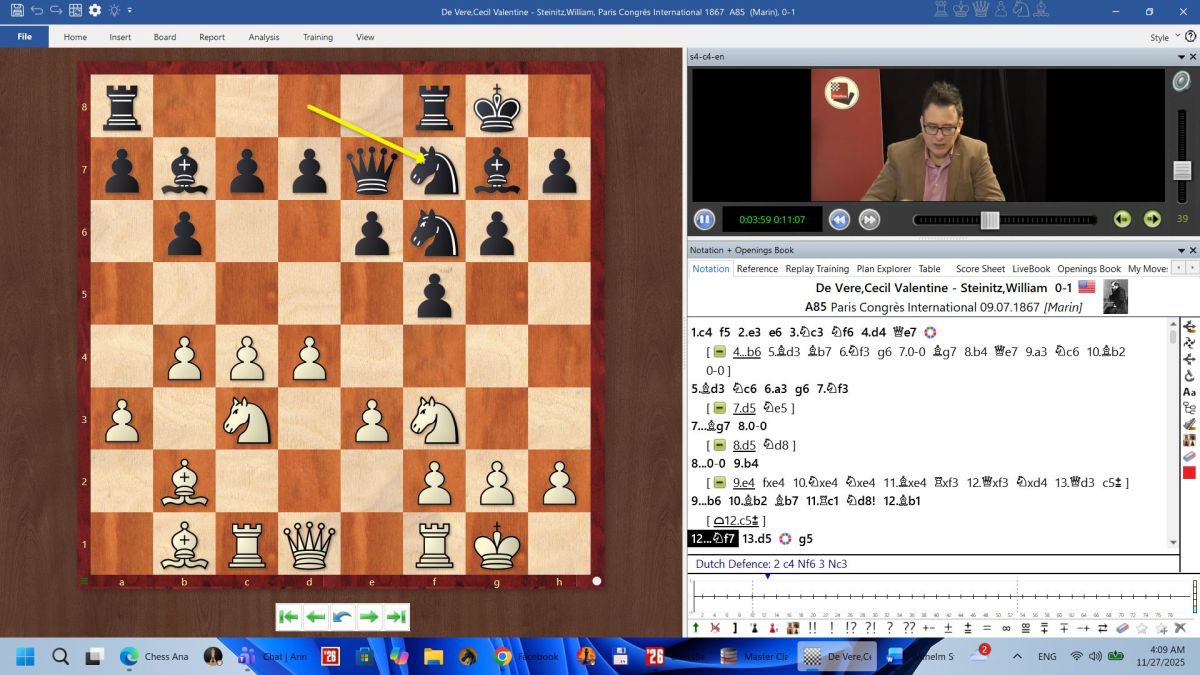

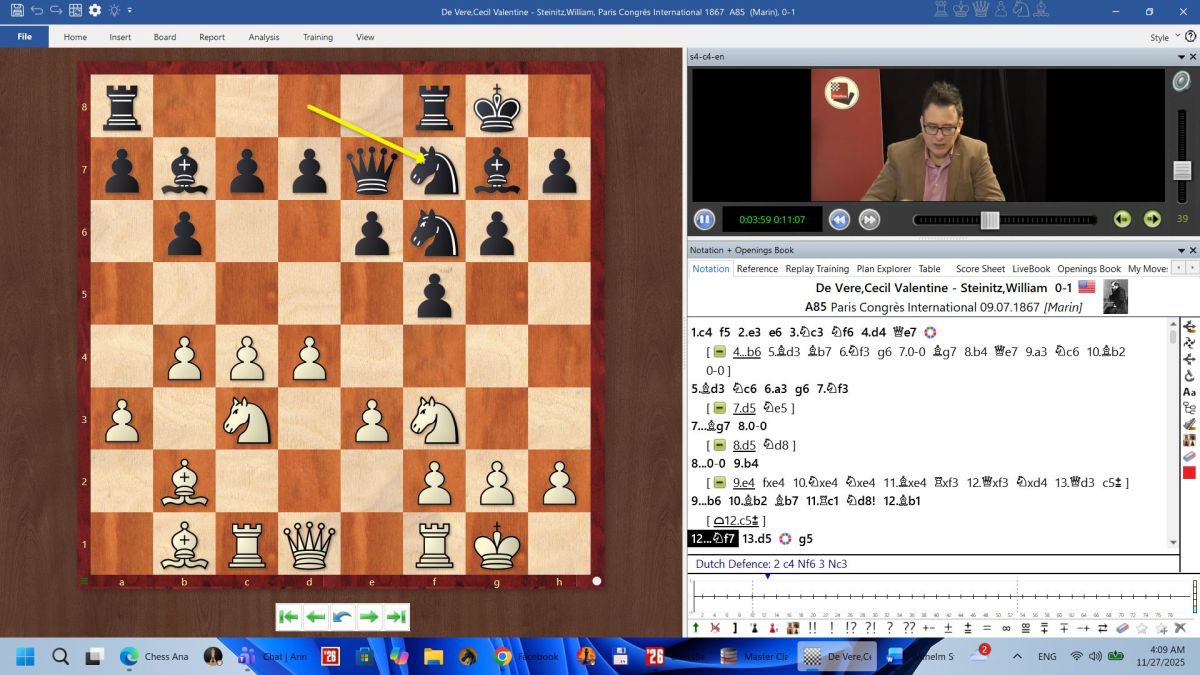

This is followed by a delightful surprise: in analyzing the game De Vere–Steinitz, Paris 1868, Marin reveals Steinitz’s astonishing talent. Steinitz plays in a hypermodern manner—many years before the hypermodernists themselves were even born! Steinitz was especially influential in developing certain defensive principles, and Marin analyzes two games (including one of his own) that demonstrate how Steinitz’s defensive ideas remain entirely applicable today.

Marin also offers a detailed examination of one of the most important games for understanding play against the isolated queen pawn (IQP): Zukertort–Steinitz, Game 7 of the 1886 world championship match. Although this game has been analyzed extensively in many sources, Marin adds the latest engine-based insights, which give his commentary exceptional value.

In short, Marin provides a genuine pleasure for the reader, presenting—in his view—the most important Steinitz games on the subjects of strategy and defense.

Steinitz and Tactics – Oliver Reeh

Steinitz is often mistakenly portrayed as merely a positional player. It is true that his most significant contribution was to the development of chess strategy, but when it comes to tactics, during the peak of his talent, he had almost no equal. Some even compared him to Morphy (!). This aspect of Steinitz’s legacy is illuminated here by IM Oliver Reeh, an excellent connoisseur of tactics and a regular ChessBase contributor in that field. Visitors of the ChessBase website are familiar with his constant stream of tactical material.

A special charm of this chapter lies in the fact that all examples are presented in training mode, which makes this section particularly engaging: by solving tactics, we not only gain pleasure but also improve our tactical understanding. Among other things, this section includes the famous Steinitz–Bardeleben game, Hastings 1895—considered one of the greatest games of all time.

A true delight for lovers of tactics.

Steinitz and Endgames - Karsten Müller

Although endgame theory in Steinitz’s time was far less developed than it would later become (even though occasional endgame analyses existed in books, the first true endgame manual—by Berger—was published only in 1891), Steinitz created genuine masterpieces in practical endgames. This chapter was prepared by arguably today’s greatest expert on endgames, GM Karsten Müller (a worthy successor to Averbakh), author of the fundamental 14-volume endgame DVD series and numerous books on the subject.

Müller addresses the question: How did Steinitz play practical endgames? Through a series of excellent examples that can—and should!—be studied even today, Müller explains various principles: restriction, how to handle the bishop pair, and more. It should be noted that Steinitz himself was the first to firmly establish that the bishop pair is an advantage, naturally, in open positions. The game English–Steinitz is so instructive that knowledge of it remains essential even today. Particularly important is the example Steinitz–Chigorin, Vienna 1898, in which Steinitz demonstrates the superiority of the bishop pair over the knight pair.

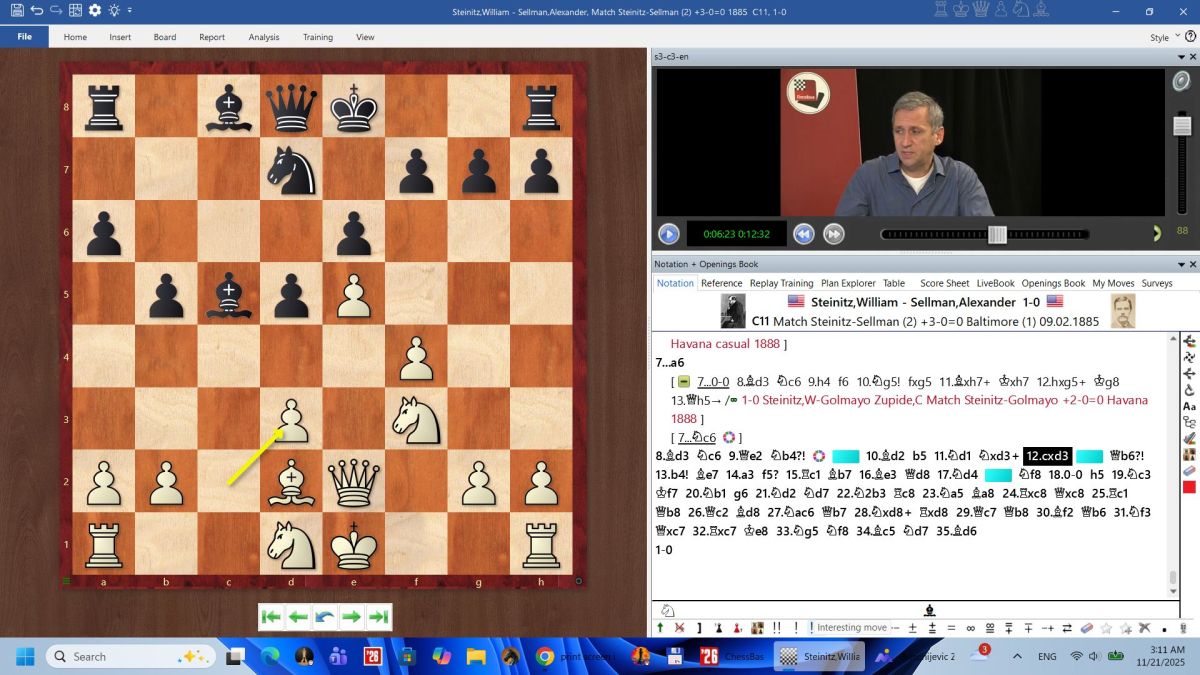

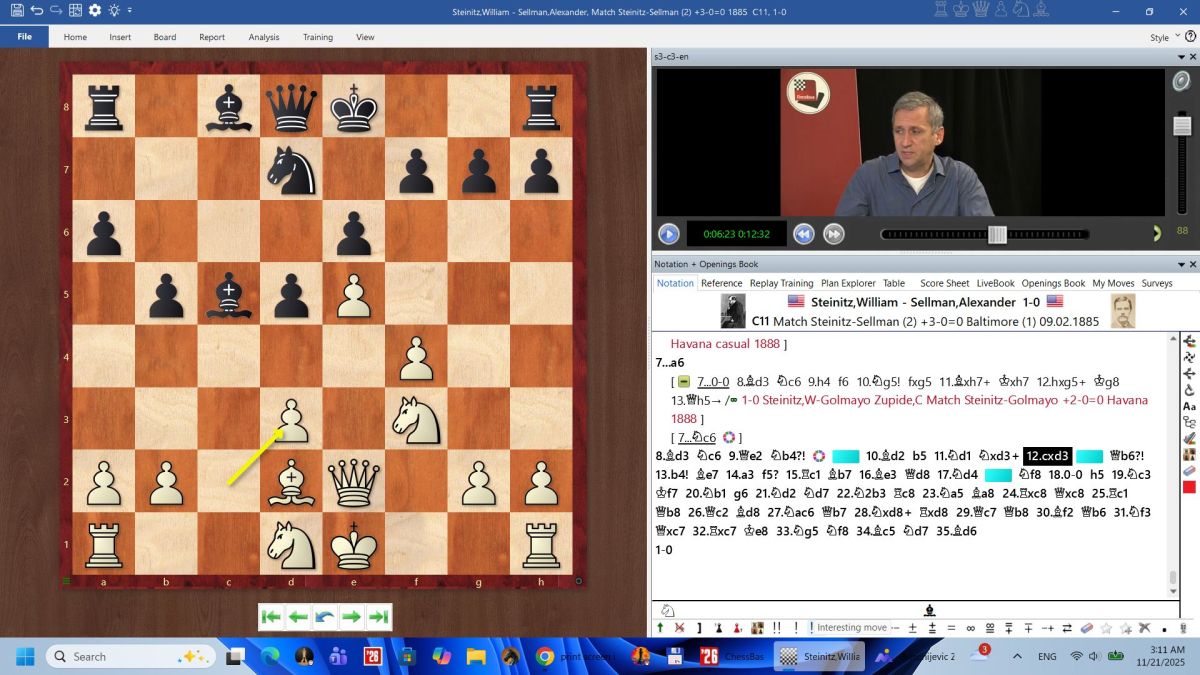

One of the most common modern themes—opposite-colored bishops in the middlegame—was well known to Steinitz. The game Steinitz–Sellman, Baltimore 1885, shows this very clearly. The classical struggle of knight versus bishop, as well as good bishop versus bad bishop, was also familiar territory for him. Speaking of transforming one advantage into another, Müller includes a lesser-known example from the Steinitz–Zuckertort match, game 12/1886. At the end, we see a beautiful pawn-versus-rook ending with theoretical relevance, presented in interactive form by Müller.

Because Steinitz played so many excellent endgames, Müller could not resist and added 11 more fascinating endings with commentary for independent study. All in all, this is a superb section that confirms the continuing necessity of studying Steinitz’s games.

At the end of the course, we find all of Steinitz’s games (some annotated), as well as his opening repertoire both with white and black. Finally, as a bonus, the material includes 22 combinations that round out the whole work.

Conclusion

With the release of the 19th Master Class video course dedicated to Steinitz, those who review all clips can expect complete enjoyment in the creative output of this unquestionably great master—and, at the same time, significant improvement in their understanding of the game. The authors—masters of their craft—use Steinitz’s most important examples to demonstrate his impact on the development of chess thought.

The clips are aimed at players from beginners up to around 2200 Elo, but they are also valuable for stronger players who, for various reasons, have not yet become familiar with Steinitz’s oeuvre. In my opinion, this is one of the highest-quality installments in the entire Master Class series.

IM Zoran Petronijevic

You will find 19 ChessBase Master Classes in the ChessBase shop:

.jpeg)

The video course belongs to the Master Class series, which currently includes 18 video courses; this one is the nineteenth in the series. The fundamental idea behind these editions is twofold: on the one hand, to acquaint us with the creative legacy of the great masters through their finest achievements, and on the other, to assist us in achieving a deeper understanding of our game. All ChessBase video courses follow the same structure: a brief biography of the player, his contribution to opening theory, strategy, tactics, and endgames. An important section includes all of the player’s games, some of which are thoroughly annotated. The subject of our text is the latest video course devoted to the first World Champion, Wilhelm (William) Steinitz (1836–1900).

The video course belongs to the Master Class series, which currently includes 18 video courses; this one is the nineteenth in the series. The fundamental idea behind these editions is twofold: on the one hand, to acquaint us with the creative legacy of the great masters through their finest achievements, and on the other, to assist us in achieving a deeper understanding of our game. All ChessBase video courses follow the same structure: a brief biography of the player, his contribution to opening theory, strategy, tactics, and endgames. An important section includes all of the player’s games, some of which are thoroughly annotated. The subject of our text is the latest video course devoted to the first World Champion, Wilhelm (William) Steinitz (1836–1900).