By Alan McGowan, Author of "Kurt Richter: A Chess Biography with 499 Games" (McFarland, 2018)

It appears that no matter how much time and energy one puts into a chess history project, the work is never done. You have worked quietly but persistently for many years, gathering information about your chosen subject. The research is fascinating, and more and more material becomes available, particularly with the coming of the internet and the ability to connect with other researchers, book dealers and archives. Eventually you reach a point where you believe you have more than enough material for a book. You reach out to a publisher with a proposal and the reply is positive.

Now the really hard work begins, because you now have to collate and order your material into a publishable shape. But while you’re doing this, you are still reaching out in many directions, octopus-like, determined to find the few details that have so far eluded you. And even after the manuscript is in the hands of the publisher, one small but important piece of information is received – something that might not even register with a reader – and you find yourself almost pleading with the book’s layout designer to allow you to tweak a few lines of text.

Now you wait for the finished product, so perhaps you can sit back and relax. But...no. There was one area of research that had troubled you, concerning a member of the subject’s family. You spent a considerable amount of time trying to resolve it, based on the one reference that was available to you, but you failed. Despite meticulously tracking the subject and his family, including his paternal grandparents, and despite poring over available archive records, you could not resolve your doubts and suspicions. However, you had reached the time when you had to decide about handing over the manuscript, so you called a halt to the research. And because the matter was not directly related to the subject of your book, you felt reasonably comfortable in deciding to leave the family with their story.

However, now you begin to worry about other matters. Although you’re convinced that your research has been thorough and wide-ranging, you begin to wonder if you overlooked something, or whether you gave insufficient attention to one area of research. And, because the project is now out of your hands, you worry about new material coming to light after the work is published.

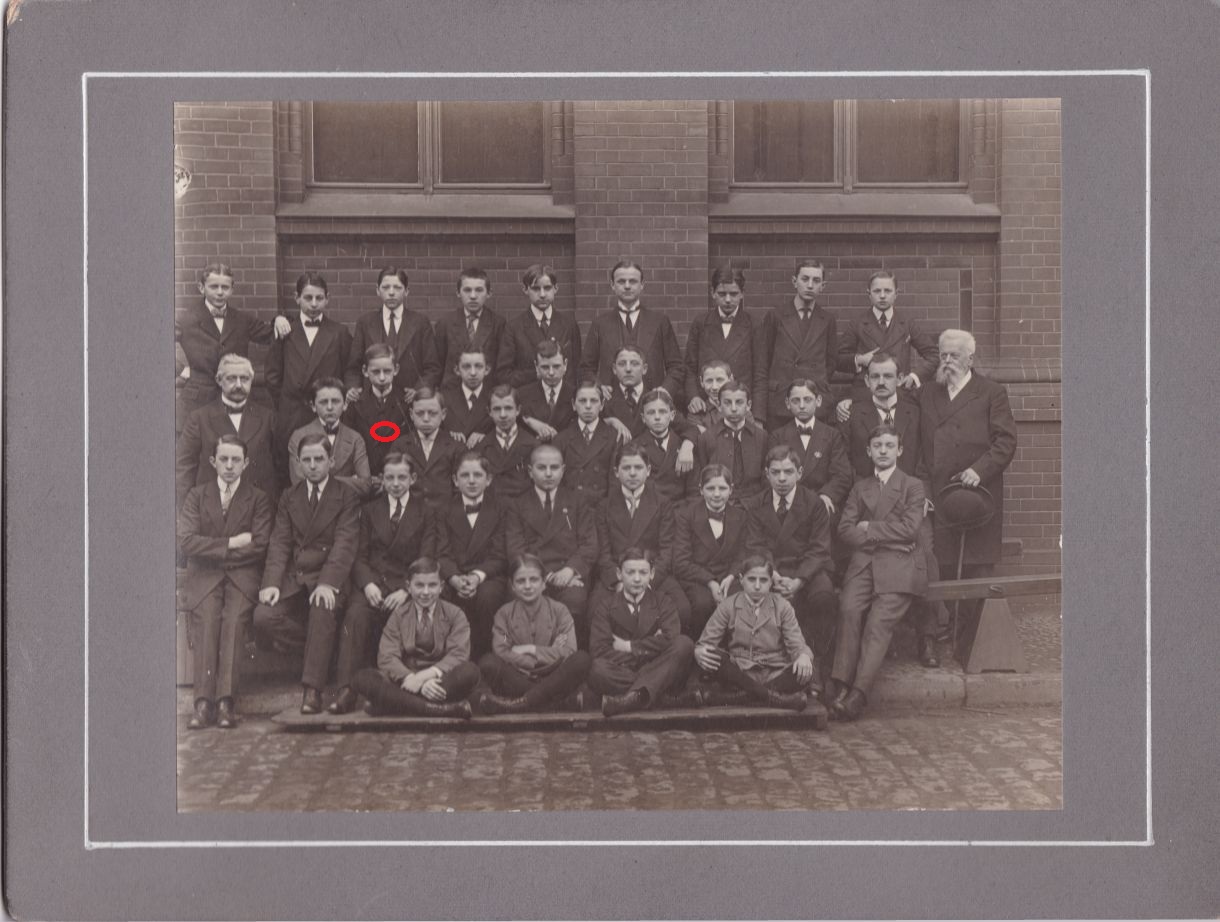

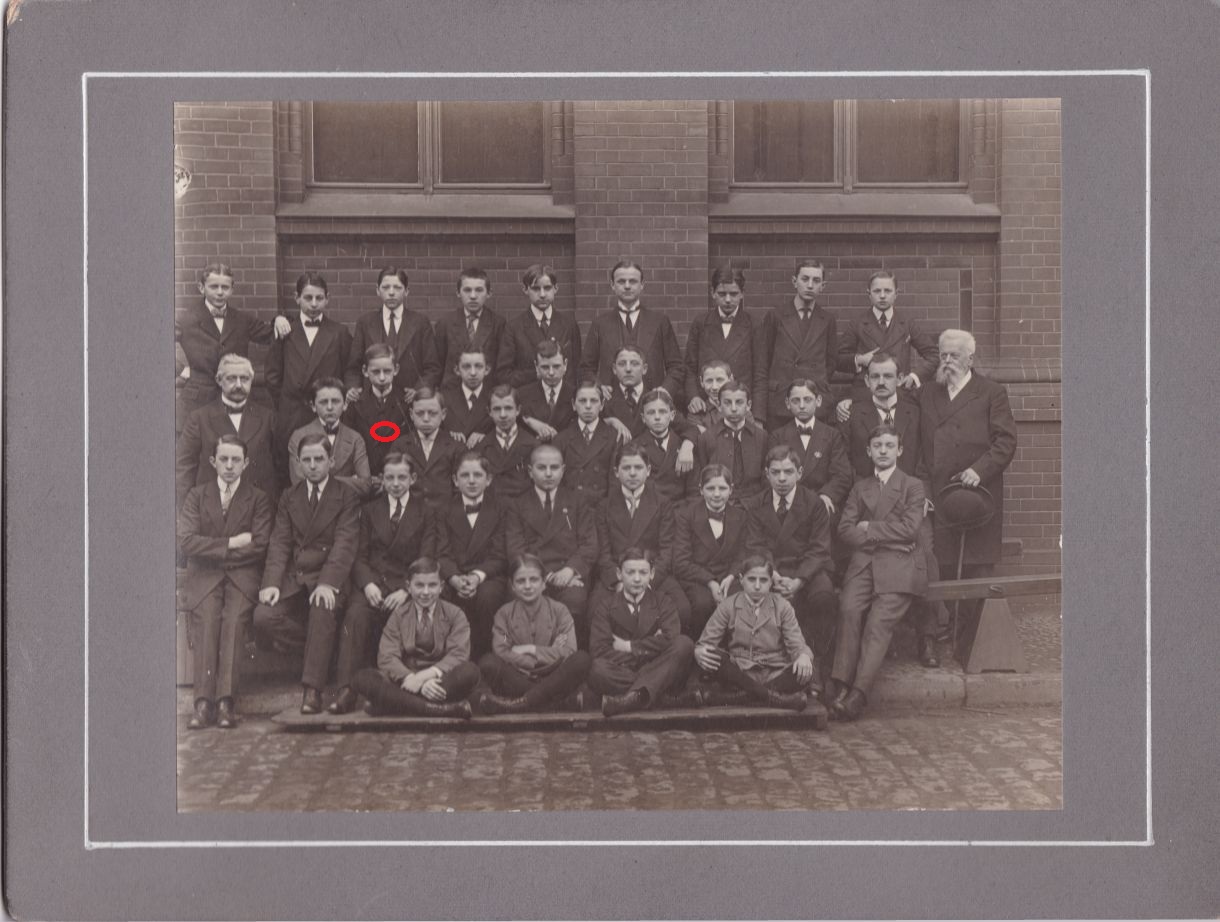

Such was the story with my book about Kurt Richter. First, within a year of its publication I was made aware of two previously unseen photographs, both of which I would have gladly used had they been made available to me. And secondly, I could not resist returning to the area of research that had troubled me previously, if only to correct a small piece of recorded historical information.

From a private collection

In many photographs, Kurt Richter put his hand to face, as if to avoid having his picture taken. In group photos it sometimes appears as if he wants to hide behind the figure in front of him. So this good quality image would have had an important place in the book. The school photograph would have enhanced the small section of information in the book about Richter’s early years.

Gerhard Richter1

I communicated with Kurt Richter’s brother Gerhard from the late 1970s through the 1980s. I was primarily interested in collecting the chess master’s games, so no personal questions were asked of Gerhard about his family. Hindsight suggests a missed opportunity.

My research continued, however, which made the idea of writing a book more feasible. But this was many years after Gerhard died, and although he had been generous with memorabilia, there were no images of Kurt Richter in his youth, hence the importance of the school photo.

School Reports

A particularly interesting research ‘find’ was a collection of Kurt Richter’s school reports from 1907-1917. An examination of those documents suggested a restlessness within the family, including Richter’s paternal grandparents. They moved from Choriner Strasse in Berlin to Friedrichshagen (where Gerhard was born), then back to central Berlin in time for Richter to attend his first school, the Gemeindeschule on Greifenhagener Strasse. He was only there for a half-year before transferring to Volkschule in Hohen Neuendorf, north of the city, which he attended until March 1909. The family then returned to familiar Berlin territory, with Richter attending the Gemeindeschule on Oderberger Strasse until the spring of 1913, before moving to his fourth and last establishment, the Realschule on August Strasse.

A particularly interesting piece of information in the school reports, which contributed to my doubts about the family story that had been presented, was that only the first three reports – the last of them dated 26 September 1908 – were signed by Richter’s father. All later reports were signed by his mother, which stood out as somewhat surprising, considering the patriarchal structure of society at the time.

Paul Richter2 – Richter’s father

Paul Richter was an Insurance Agent (Versicherungs Beamter), which probably explains why Kurt entered the insurance world after leaving school. According to issue 3/1970 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, Paul Richter was killed in France in 1914, in the early days of WW1. This information was included in a tribute to Kurt Richter, who died 29 December 1969. The article was compiled by Theo Schuster, with contributions by Gerhard Richter. There was no reason to doubt this information, though I did wonder how an insurance agent in his mid-40s (born 1868) turns up on the front lines in the early days of the war.

Otto Richter3 – Richter’s paternal grandfather

Otto Richter, who taught chess to Kurt Richter, appears to have been a central figure for the family. He was a Master Tailor (Schneidermeister), who moved with them to Friedrichshagen in 1903. On returning to the familiar ground of central Berlin, his home was at Rhinower Strasse 4.

But keeping track of some of the family’s movements became difficult. I lost sight of Richter’s father, Paul, and could not place him and Richter’s mother, Rosa,4 together at the same address. I then discovered that Rosa was recorded as a tenant in her own right, first at Choriner Strasse, and, in 1916, at Zionkirch Strasse 20.5 What was significant about those entries in the Berlin Address Books was that Rosa Richter was not shown as a widow, as she should have been if her husband had died in 1914.

This inconsistency, along with the father’s disappearance from school reports and my failure to find a 1914 death record for Paul Richter was troubling. It was natural to consider separation and/or divorce, but I did not speculate about that in my book.

Endpiece

As feared, interesting new material did appear after the book was published. The above photographs likely prompted me to review my thoughts about the inconsistencies which had annoyed me. So, despite the 1970 obituary, compiled with the help of Gerhard Richter, I was unable to dispel the doubts raised by the various clues. It took a while, but eventually I returned to searching genealogy records, which resulted in confirming that Kurt Richter’s father, Paul Richter, did not die in 1914.

Was it necessary to make that search? No. Does it serve any real purpose? Perhaps. It certainly corrects information provided by Gerhard Richter to a reputable German chess periodical. And it allows me to now correct a statement in my book.

Did Gerhard make up the story about the 1914 death because he had been told that was what happened? Did the parents simply drift apart? Did Paul Richter serve in the war, returning injured to Berlin? Did he acquire a debilitating illness that required special treatment? So many questions.

Kurt Richter’s father, Paul, died 13 January 1918 at Buch, by Berlin, an area known for many retirement homes and hospitals.6 This was one day after the death of his grandfather, Otto.7

Did the brothers know of the loss of two significant figures in two days? Perhaps.

But that’s another story.

NOTES

1. Gerhard Friedrich Otto Wilhelm Richter (1903-1997)

2. Paul Otto Friedrich Carl Richter (1868-1918)

3. Carl Otto Gustav Adolph Richter (1839-1918)

4. Rosa Richter, née Poschmann (1875-1952)

5. Zionkirch Strasse 20 was Kurt Richter’s recorded home address from when he became known to the Berlin chess community, until he moved in 1935 to Dönhoff Strasse 29, Berlin-Karlshorst.

6. His death record (Nr. 60, Buch, 14 January 1918) errs in showing his name as Paul Otto Gustav Richter (Gustav was part of his father’s name).

7. Death record Nr. 80, Berlin, 14 January 1918. He died at Schul Strasse 97-98, Berlin.

Alan McGowan: A rich chess life: Berlin Chess Cafés 1920-1933