Constructing a national identity

Chess occupies a discreet yet decisive place in the English philosophical and literary tradition. Unlike cultures that have elevated the game to a national emblem or ideological model, England has granted it a more ambiguous but equally fertile role: a mirror of mental processes, a field for logical experimentation and a metaphor for identity, morality and uncertainty. From empiricist philosophy to literary fantasy, chess has been explored less as doctrine than as experience - intimate, paradoxical and revealing.

During the nineteenth century, England underwent profound transformation. The Industrial Revolution, imperial expansion and the emergence of new social classes reshaped daily life and altered the English understanding of culture itself.

The aim of these Dvd's is to build a repertoire after 1.c4 and 2.g3 for White. The first DVD includes the systems 1...e5, the Dutch and Indian setups. The second DVD includes the systems with 1...c5, 1...c6 and 1...e6.

The aim of these Dvd's is to build a repertoire after 1.c4 and 2.g3 for White. The first DVD includes the systems 1...e5, the Dutch and Indian setups. The second DVD includes the systems with 1...c5, 1...c6 and 1...e6.In Victorian England, culture was closely associated with refinement, education and good taste. To be "cultured" implied familiarity with literature, art, music and social manners, an ideal especially prized by the rising middle class. Formal education and engagement with canonical works were viewed as paths to personal improvement and social mobility. Culture thus became linked to the idea of a civilising mission: the belief that education and progress should extend beyond Britain’s borders.

The period witnessed the expansion of popular culture as well. Serialised novels, theatre, music halls, sports and public spectacles flourished alongside elite forms such as opera and fine art. Writers like Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy gave literary form to the experiences of the working classes, demonstrating that culture was not the exclusive preserve of the aristocracy.

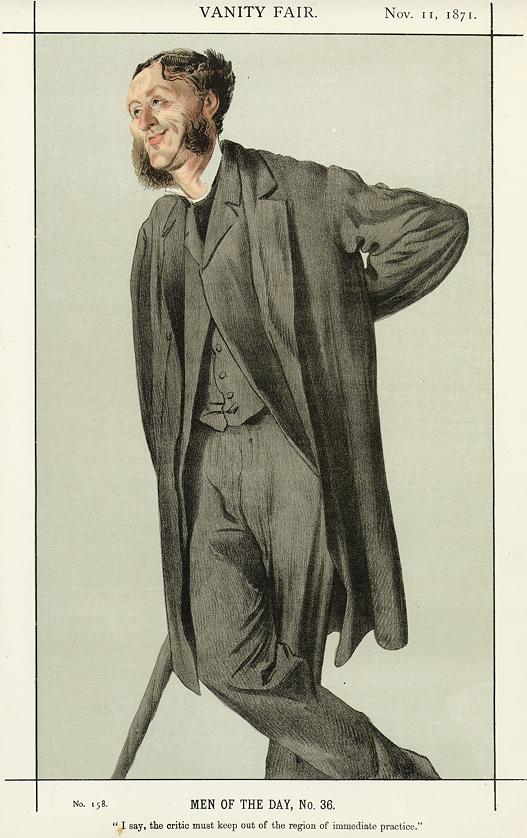

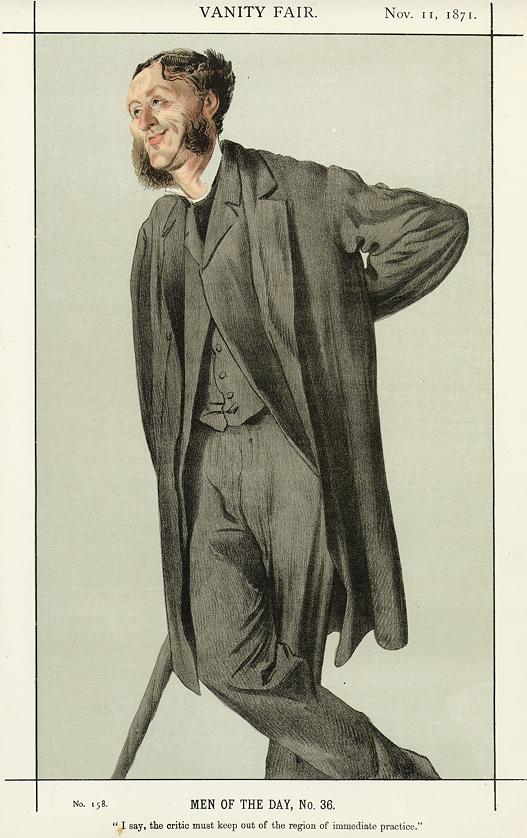

Thinkers such as Matthew Arnold reflected critically on culture as a means of achieving "human perfection" and as a corrective to social disorder. In Culture and Anarchy (1869), Arnold defined culture as the pursuit of "the best that has been thought and said" and presented it as an antidote to materialism and intellectual complacency.

Caricature of Matthew Arnold, captioned: "I say, the critic must keep out of the region of immediate practice" | Published in Vanity Fair, 11 November 1871 (public domain)

Culture also became central to the construction of English national identity. Shared language, traditions, history and institutions acquired renewed importance, serving as bonds of cohesion during a period of rapid change. In this sense, culture functioned simultaneously as inheritance, aspiration and critique.

Within this intellectual climate, chess found a natural place. Figures such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke lived at a time when chess was popular among educated circles. Although neither wrote directly about the game, their empiricist conception of knowledge as arising from ordered experience resonates strongly with chess. The game offers a structured symbolic environment in which perception, memory, comparison and anticipation - core elements of empiricist thought - are constantly exercised.

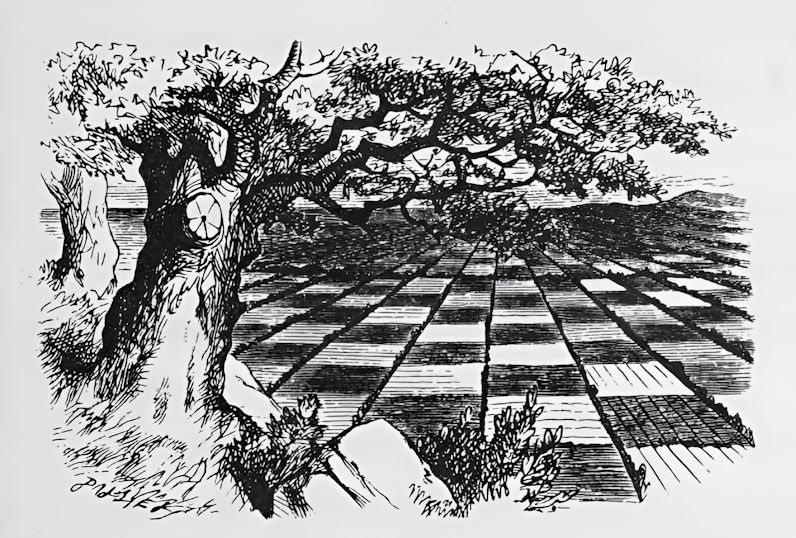

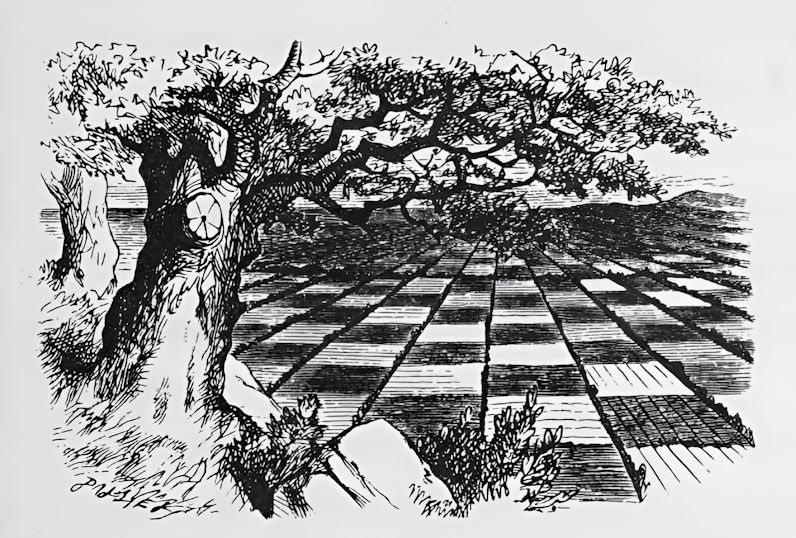

Chess assumes a particularly central symbolic role in the works of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll. A logician, mathematician and storyteller, Carroll made chess the organising principle of Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (1871). Each chapter corresponds to a move in a carefully constructed game. Alice begins as a pawn and advances until she is crowned queen. Yet this progression is not merely allegorical: the chessboard becomes a space of paradox and playful logic that destabilises identity, language and time.

Carroll's chess is infused with logical humour. The pieces speak and follow rules that appear formally coherent yet collapse into absurdity when applied to lived experience. This fusion of rational structure and nonsense anticipates later philosophical concerns, particularly those associated with Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Daniel Gormally shows how to combine strategic and attacking ideas in the sicilian. Use the english attack as a lethal weapon!

Daniel Gormally shows how to combine strategic and attacking ideas in the sicilian. Use the english attack as a lethal weapon!

Illustration from "Through the Looking Glass" (1871)

Wittgenstein did not write explicitly about chess, but the game is implicit in his reflections on rules, meaning and "language games". In Philosophical Investigations (1953), he presents games as systems governed by finite rules yet capable of infinite applications. Chess thus exemplifies how meaning emerges from use within a structured context: a chess "king" signifies only within the practices that sustain the game.

English literature has also cultivated a chess tradition, though sometimes through later reinterpretation. Shakespeare is often cited for a supposed chess scene in The Tempest involving Miranda and Ferdinand. This scene, however, is apocryphal. It originates in William Davenant's 1674 adaptation, not in Shakespeare's original text.

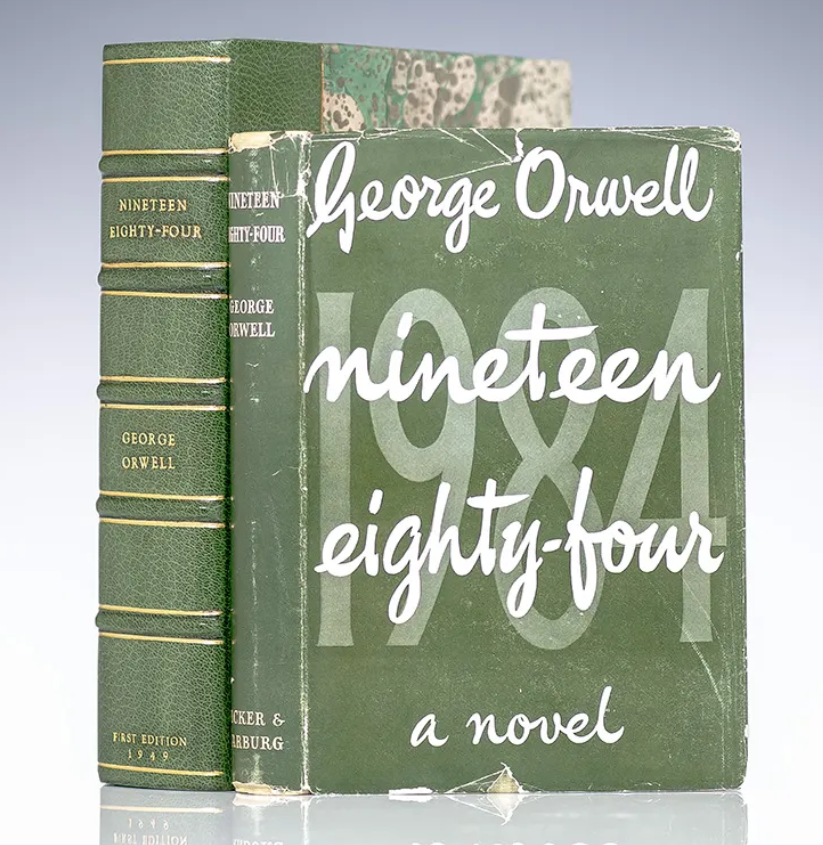

In the twentieth century, chess acquired a political and existential dimension in the work of George Orwell. In Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), a brief chess reference carries heavy symbolic weight: Winston recognises that truth has been replaced by the logic of power. The assertion that "white always wins" transforms chess into a metaphor for a manipulated reality where outcomes are predetermined by authority.

Chess also surfaces in modernist poetry. In The Waste Land (1922), T. S. Eliot titles one of its most unsettling sections "A Game of Chess", using the game as a symbol of emotional exhaustion and failed communication in the modern world.

First-edition cover of George Orwell's "Nineteen Eighty-Four" | Photo: Raptis Rare Books

Beyond literature, Britain has produced influential chess figures such as Howard Staunton, a leading nineteenth-century player, editor and organiser of the 1851 London tournament. Staunton viewed chess as a cultural practice and a discipline of the mind, an outlook reflected in the enduring design that bears his name.

In contemporary philosophy, Roger Scruton considered chess an example of moral aesthetics. For Scruton, chess demonstrates how order, limitation and respect for form allow beauty to emerge. Excellence lies not merely in victory, but in style, restraint and judgment.

The English tradition has approached chess with a balance of logical rigour and literary sensitivity. Rather than idealising it, English thinkers and writers have explored chess as a philosophical tool, a cultural symbo, and a narrative structure. From Carroll to Orwell, from Staunton to Wittgenstein, chess in England has functioned less as doctrine than as reflective experience: a way of thinking under rules and of acting with consequence.

Sources

Your personal chess trainer. Your toughest opponent. Your strongest ally.

Your personal chess trainer. Your toughest opponent. Your strongest ally.

FRITZ 20 is more than just a chess engine – it is a training revolution for ambitious players and professionals. Whether you are taking your first steps into the world of serious chess training, or already playing at tournament level, FRITZ 20 will help you train more efficiently, intelligently and individually than ever before.

- Amis, M. (2002). Time's Arrow. Vintage International.

- Black, J. (2013). Chess and English Culture, 1850–1900. Manchester University Press.

- Blanco-Hernández, U. (2025). Ajedrez y Filosofía: el Tablero como Arquetipo del Mundo Interior. Editorial Jaque Mate, México.

- Blanco-Hernández, U. (2020). ¿Transitó el ajedrez la tortuosa ruta de la seda hasta las arenas de Alejandría? Ciencia y Deporte, 5(2), 97-116.

- Carroll, L. (2002). A través del espejo y lo que Alicia encontró allí (A. de Yturriaga, Trad.). Valdemar.

- Eliot, T. S. (2001). La tierra baldía (J. Luis Etcheverry, Trad.). Cátedra.

- Lewis, D. (1973). Counterfactuals. Harvard University Press.

- Locke, J. (2005). Ensayo sobre el entendimiento humano (L. E. Rodríguez, Trad.). Ediciones Cátedra.

- Orwell, G. (2016). 1984. Debolsillo.

- Russell, B. (1996). La conquista de la felicidad. Edhasa.

- Shakespeare, W. (2002). La tempestad (A. Valbuena Briones, Ed.). Espasa-Calpe.