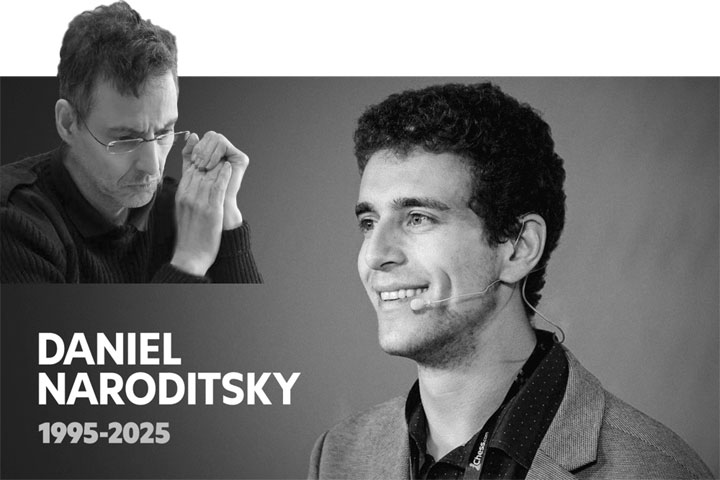

Reactions to the young and highly regarded grandmaster's passing have poured in, compassionate and generous, as people have willingly shared their encounters and experiences with Naroditsky, both online and in person.

The statement invites deeper questions about the (alleged) community (Gens una Sumus): What are we doing, why and how? We often hear about the many excellent qualities chess is said to teach, but perhaps attendance was thin the day virtue, with roots in Aristotle's arete and the Romans' virtus, was on the syllabus.

Virtue originally referred to what makes something function well, for example how a sharp knife is able to cut. It is not innate but can be learned; everyone has, at least in principle, the potential for it. Today, the concept occurs mainly within ethics.

Examples of specific virtues include courage, generosity, honesty, judgement, moderation (sophrosyne), prudence, objectivity, righteousness and truthfulness – qualities many responses testify Naroditsky himself embodied, in life as well as in teaching (no, no one is an angel). Virtues describe not just actions but character, who we are as human beings. For example, honesty as a virtue involves not only refraining from lying but also a way of thinking and feeling, such as valuing truthfulness.

Lasker famously said that chess is a battle between minds, but what is the relationship between chess' stated norms, ideals and practices? Is chess merely a peaceful competition or is perhaps something else hiding behind our neurons and synapses?

Some reactions in the wake of Naroditsky's death, not only against the aforementioned former top player but also among those responding, suggest that chess, perhaps more than other activities, is in essence tribal warfare by other means: Pawns and knights replace spears and slingshots, but the motivation is the same; defeat your opponent, whatever the cost.

Some reactions in the wake of Naroditsky's death, not only against the aforementioned former top player but also among those responding, suggest that chess, perhaps more than other activities, is in essence tribal warfare by other means: Pawns and knights replace spears and slingshots, but the motivation is the same; defeat your opponent, whatever the cost.

Picture: Daniel Naroditsky at his home in Charlotte, N.C. Credit...Travis Dove for The New York Times.

Reactions and behaviour, before and after Naroditsky's passing, on and off the board, from bickering and carping, to misinterpretations, misunderstandings, and ad hominem attacks, testify that something is at stake, in Gadamer’s words, but what? Do chess games mirror the comments sections, or vice versa? Do chess players have a greater need for self-assertion than other athletes, although other sports are no strangers to inflated egos? What about social media and their keyboard warriors – another extension of the tribal fight? It has been suggested that what you wouldn't say to someone face to face, you should keep to yourself.

If chess is our only source of income, it's understandable that things can get heated from time to time, but what is a man profited, if he shall gain the whole world, yet forfeit his soul?

Because we never know what our opponents or online debaters have been through before our game or our encounter with tonight's comments section, it might be worth reminding ourselves why we play chess or comment online: Ego pampering? Aesthetics and mysticism? Honour and glory? To learn? +Trophies and rating points? Self-affirmation? Self-assertion? Creating something we can remain proud of afterwards?

The situation is reminiscent of today's mantra where store employees send their customers off with a cheerful, ‘Have a (still) nice day!’ But what do they know? ‘Today the wife filed for divorce, the car stolen, the house burned down, the kids kidnapped, and the dog ran off. Have a nice day!?’

One day we might realise that we'll never be world champion anyway, and it might be reasonable to adjust our approach, while our shoulders and ambition level are lowered, but do the virtues of chess really have to give way in the heat of battle?

However, once the damage is done (as we all know, few people are angels), if we still have time to become conscious of what we’re about to, we could try to catch ourselves before shooting from the hip, over as well as outside the board.

Could the loss of Naroditsky serve to broaden our perspective, or are we living in a time when we know the price of everything, but the value of nothing?

Previous articles by Rune Vik-Hansen

Some reactions in the wake of Naroditsky's death, not only against the aforementioned former top player but also among those responding, suggest that chess, perhaps more than other activities, is in essence tribal warfare by other means: Pawns and knights replace spears and slingshots, but the motivation is the same; defeat your opponent, whatever the cost.

Some reactions in the wake of Naroditsky's death, not only against the aforementioned former top player but also among those responding, suggest that chess, perhaps more than other activities, is in essence tribal warfare by other means: Pawns and knights replace spears and slingshots, but the motivation is the same; defeat your opponent, whatever the cost.