The name of the game is domination

By Albert Silver

With Magnus Carlsen's Elo skyrocketing past Mars, the big talk is on the record rating and how far he can take it. The secondary talk, and quite understandable, is how this compares with past ratings, and whether the record is indeed a record.

Magnus Carlsen skyrocketing past Mars

Magnus Carlsen skyrocketing past Mars

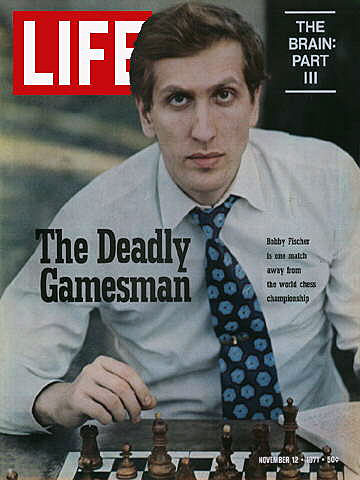

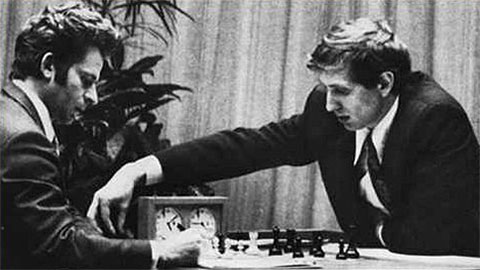

When discussing the highest rating, the first issue to come up is the nebulous and endless discussion of ratings inflation, a real issue which makes direct comparisons nearly impossible without a constant shade of doubt forever cast on any record. In fact, this exact same discussion came up in 1989 when Garry Kasparov, rated 2775, was knocking on the door of Bobby Fischer’s hitherto record of 2785, set in 1972.

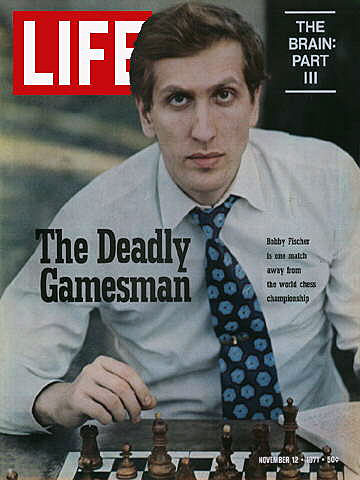

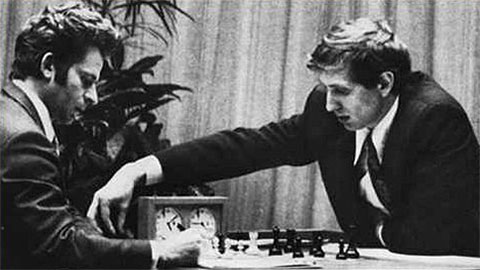

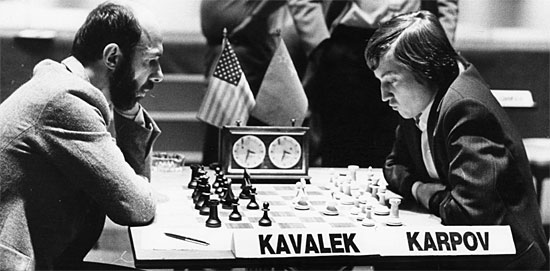

Bobby Fischer became a household name all over the world

Bobby Fischer became a household name all over the world

His one man quest for the title, and sheer domination fired the imagination of fans everywhere

His one man quest for the title, and sheer domination fired the imagination of fans everywhere

The argument is just as valid today as it was then, and sadly there is also no question that comparing the pure ratings of the past with the present is an exercise in futility. The factors causing inflation are still unclear, as well as by how much, and though numerous estimates exists, declaring records in such circumstances is to tread on thin ice indeed. When consulted on the subject, renowned statistician Jeff Sonas agreed, "Of course it is a huge question how to calibrate the entire list, and what the overall magnitude of the ratings is, so I prefer as well to talk about the gap between players, rather than '2900'." Ultimately though, it doesn’t really matter.

The reason stems from a common misunderstanding of how Elo ratings are calculated. Elo does not measure absolutes, nor does it even measure chess strength on its own. It measures how well one player does against another, and the rating is then calculated to show the difference between the players. With no one to compare to, Carlsen’s rating would not be measuring a thing.

Why is this relevant? When a time is set in the 100 meter dash, the time is an exact measurement in and of itself. You cannot remove three seconds from everyone in a 100 meter race and claim it is still completely accurate. The rankings in the race would still hold, but the times would not. On the other hand, if every single rating in the Elo list had 500 Elo removed from the scores, it would still be 100% accurate! The reason is because everyone's rating differences would still be the same, and thus correct.

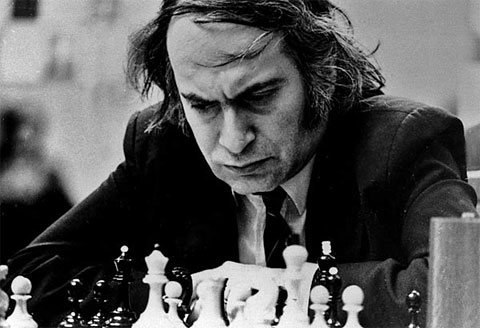

It is important to put this in perspective, otherwise past great performances become lost as a result of pointless comparisons. For example, in January 1980, the number one player in the world was Anatoly Karpov, rated 2725. What matters is that he was no.1, and not the number. Second in the list was the astonishing Mikhail Tal, who was rated 2705. Again, the absolute number, which today would barely rank a player in the top 40, is irrelevant! What really matters is that 20 years after he had been world champion, the mighty Tal was in such form that he was back to number two in the world and only 20 Elo behind the world number one!

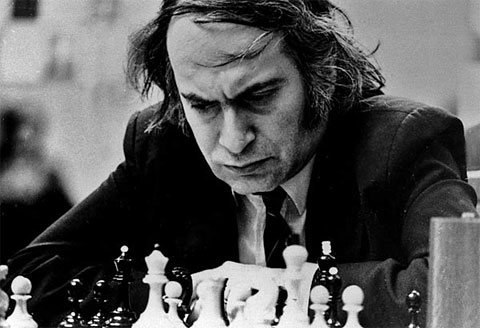

Mikhail Tal was the number one guy to beat in 1960...

Mikhail Tal was the number one guy to beat in 1960...

...and 20 years later was within spitting distance of the number one spot once more.

...and 20 years later was within spitting distance of the number one spot once more.

So does this mean Magnus Carlsen’s result is any less meaningful? Absolutely not. For one, he is the clear number one, and second, he is one of the most dominating players in Elo history, within a fraction of overtaking Anatoly Karpov’s record third best.

What record you might ask? What third best? Since the Elo still calculates the difference between players just as well as 40 years ago, one can perfectly well compare the players then and now to see which number one player has achieved the greatest domination over his peers.

When Bobby Fischer set his 2785 record rating, the record was not so much in that single number, but the difference between him and the number two player, Boris Spassky at 2660. His real record was being 125 Elo more than his closest rival. The same is true of Kasparov’s 2851. The number alone was quite meaningless in and of itself. What was meaningful was the 82 Elo advantage it stated he held over his closest rival: Vishy Anand, rated 2769 in the same rating list. As a matter of fact, if you take Karpov out of the equation, then in January 1990, Garry Kasparov was 120 Elo over the third best player, Jan Timman.

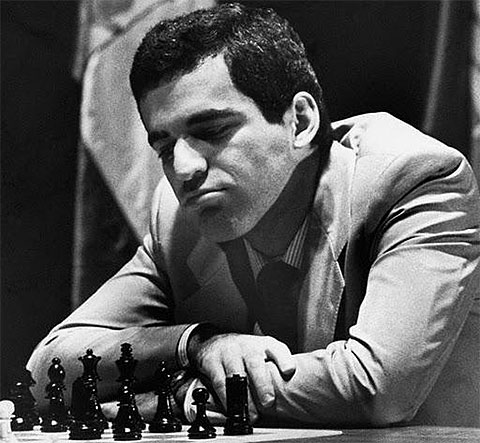

Young Garry Kasparov already setting the standard

Young Garry Kasparov already setting the standard

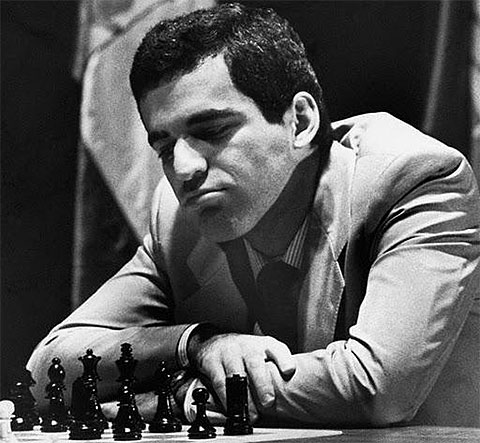

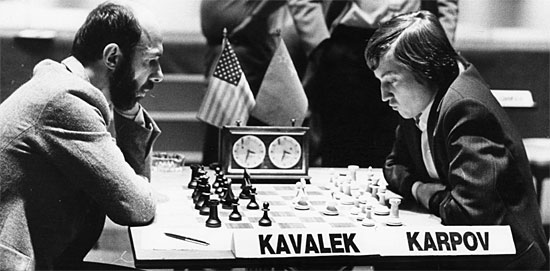

Naturally, you cannot overlook the great Anatoly Karpov, who in January 1982 was no.1 with a fantastic 65 Elo edge over world no.2 Jan Timman. This is the third most dominant performance by a world number one since the Elo inception.

Anatoly Karpov had to live in the shadow of his predecessor for a long time, but his domination

Anatoly Karpov had to live in the shadow of his predecessor for a long time, but his domination

could not be argued with.

Magnus Carlsen, in the latest ratings list, is a very close 4th with 62 Elo over the world number two, and looks more than likely to overtake Karpov’s record soon enough. Should he manage to open an 83 Elo difference, then he will pass even Kasparov.

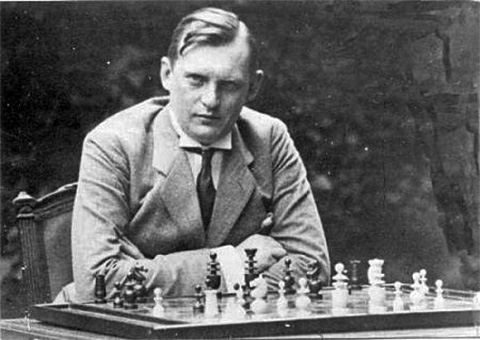

What about other past greats, prior to the Elo system? There can be no question that if it were possible to include champions such as Alekhine, Capablanca, and others, the following list would look different, but since the use of the Elo system 44 years ago, this is how the list looks.

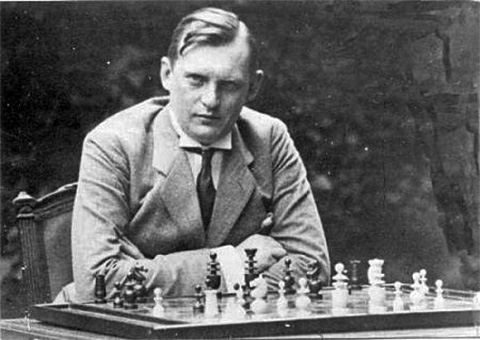

There is no question that other great champions, such as Alexander Alekhine have

There is no question that other great champions, such as Alexander Alekhine have

a place reserved on the list.

Historically, the greatest Elo gaps by any champion since 1971 are:

Largest official Elo gaps

| Rk |

Name

|

Elo edge

|

Date of publication

|

| 1 |

Robert Fischer |

125

|

|

| 2 |

Garry Kasparov |

82

|

|

| 3 |

Anatoly Karpov |

65

|

|

| 4 |

Magnus Carlsen |

62

|

|

| 5 |

Veselin Topalov |

34

|

|

| 6 |

Viswanathan Anand |

23

|

|

Elo expert Jeff Sonas, owner of Chessmetrics, felt that only comparing the top player against the second might not show the genuine domination over his immediate rivals, and only one. As a result, here is a table sharing the largest recorded difference between the number one player and the number five.

Largest official Elo gap between no.1 and no.5

| Rk |

World number one |

Elo edge

|

Date of publication

|

| 1 |

Garry Kasparov |

155

|

|

| 2 |

Robert Fischer |

145

|

|

| 3 |

Anatoly Karpov |

95

|

|

| 4 |

Magnus Carlsen |

86

|

|

| 5 |

Veselin Topalov |

71

|

|

| 6 |

Viswanathan Anand |

34

|

|

Among the players who steamrolled their rivals in the 20th century

Among the players who steamrolled their rivals in the 20th century

is the great Cuban genius (such an over-used accolade and so

accurate) José Raúl Capablanca.

How could one overlook the mighty Mikhail Botvinnik?

How could one overlook the mighty Mikhail Botvinnik?

Finally, just for reference here is the table using the more significant Chessmetrics measurements since 1900.

Largest Elo gap since 1900 (including historical Chessmetrics)

| Rk |

Name

|

Elo edge

|

Date of publication

|

| 1 |

Robert Fischer |

125

|

|

| 2 |

Mikhail Botvinnik |

122

|

|

| 3 |

José Raúl Capablanca |

119

|

|

| 4 |

Alexander Alekhine |

93

|

|

| 5 |

Garry Kasparov |

82

|

|

| 6 |

Emanuel Lasker |

72

|

|

| 7 |

Anatoly Karpov |

65

|

|

| 8 |

Magnus Carlsen |

62

|

|

| 9 |

Veselin Topalov |

34

|

|

| 10 |

Viswanathan Anand |

23

|

|

* Chessmetrics calculation

** According to Chessmetrics, Lasker actually peaked in May 1894 with a 105 gap. After 1900, his strongest period was in January 1911. For what it's worth, when he came out of retirement, he enjoyed yet another phase as the clear number one player, when in August 1925 he was outperforming the world champion, Capablanca, by 37 Elo. He was 56 years old at the time.

For further reading on the subject, I would like to recommend the fascinating articles by Jeff Sonas "The Greatest Chess Player of All Time" (Parts 1,2,3 and 4)

Copyright ChessBase

Mikhail Tal was the number one guy to beat in 1960...

Mikhail Tal was the number one guy to beat in 1960... ...and 20 years later was within spitting distance of the number one spot once more.

...and 20 years later was within spitting distance of the number one spot once more.  Young Garry Kasparov already setting the standard

Young Garry Kasparov already setting the standard  Anatoly Karpov had to live in the shadow of his predecessor for a long time, but his domination

Anatoly Karpov had to live in the shadow of his predecessor for a long time, but his domination

Among the players who steamrolled their rivals in the 20th century

Among the players who steamrolled their rivals in the 20th century How could one overlook the mighty Mikhail Botvinnik?

How could one overlook the mighty Mikhail Botvinnik?