Paul Morphy is one of the most fabled chess players. The scion of a wealthy and distinguished family in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, his extraordinary talent was discovered early. Barely out of his teens and too young to practice the legal profession, he embarked on what is arguably the greatest international campaign of all time.

His exploits are as impressive today as they were back then. As a child, he swept a three-game encounter against the visiting Hungarian master, Johannes Lowenthal. Seven years later, he became the second champion of the United States when he took the First American Chess Congress of 1857 at the expense of another European master, the German Louis Paulsen.

His genius having become apparent, the New Orleans Chess Club challenged Europe’s best to test their mettle against him. When no one accepted, reluctant as the masters of the old world were to travel far and face an unknown opponent, Morphy sought them all out. “He felt his enormous strength,” a childhood friend said, as Morphy was raring to cross the Atlantic.

It was an epic conquest that now defines his regretfully short career. In England, Morphy beat Thomas Barnes (19-7), John Owen (4-1), Samuel Boden (6-1), Henry Bird (10-1), and Lowenthal, once again, (9-3). Sailing to France, he defeated Daniel Harrwitz (5-2) and, finally, the great Adolf Anderssen (7-2).

In a time when Europe was the unquestioned superpower of chess, Morphy left everyone flabbergasted with his single-handed domination of the continent’s masters. On his return home, he was feted with a hero’s welcome.

Alas, Morphy’s aristocratic upbringing had him resolve never to play chess publicly and for stakes ever again. With his brilliant tour, nonetheless, he became quite the measure of every other American player.

Morphy, perhaps, so inspired his countrymen that his tale - that of the American prodigy crossing to Europe for his defining, glorious conquest - seemed to recur thereafter. To be sure, Morphy is all in a class of his own and the scale of his success was not to be equaled, but other players emerged who were great in their own right, and whose achievements were very consequential as well.

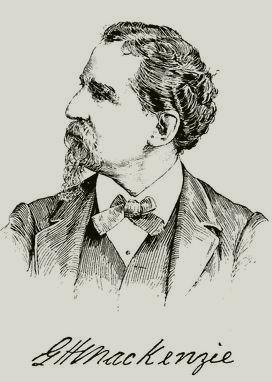

The first of these American masters to mirror Morphy’s success was George Henry Mackenzie. He was born in the same year as Morphy, 1837, and like Morphy before him whose roots were Irish, Mackenzie was a Scottish immigrant. While working as a soldier in Europe, he developed into a strong player. He resigned from service, however, to immigrate to the United States, and fought for the Union in the American Civil War.

George Henry Mackenzie

After the war, Mackenzie became a chess professional and established himself as the USA’s strongest player. From 1865 to 1880, he won all the thirteen tournaments he entered, which included the New York Chess Club’s annual contests in 1865, 1866, 1867, and 1868. He also won Cleveland 1871, Chicago 1874, and New York 1880, which were the second, third, and fifth American Chess Congresses, respectively, the equivalent of today’s US Championship. He was simply too tough for everyone at home, and was obviously made for the far stronger masters and stiffer competition of Europe.

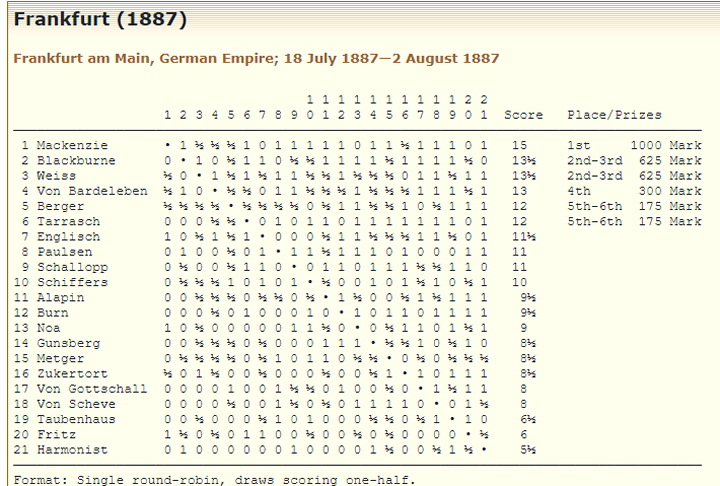

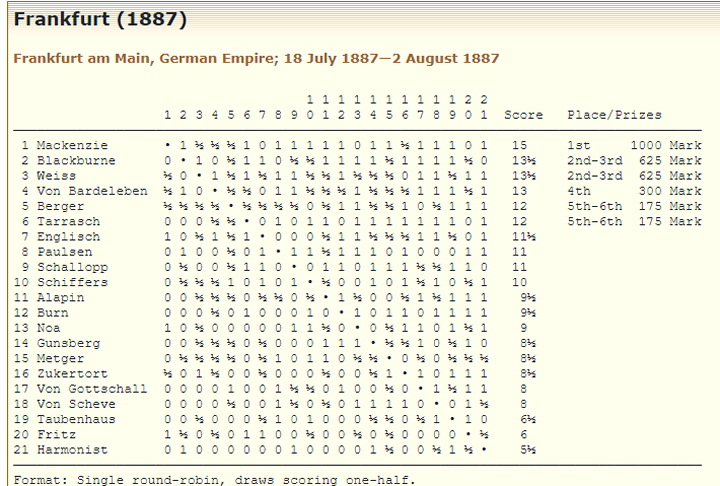

Mackenzie did seek the European challenge. His first international foray was in Paris 1878, where he placed 4th. His moment came in 1887 when he won the super tournament in Frankfurt ahead of such outstanding players as Joseph Henry Blackburne, Johannes Zukertort, Berthold Englisch, Max Weiss, Curt von Bardeleben, Siegbert Tarrasch, and Paulsen (Morphy’s rival in the 1857 American Chess Congress).

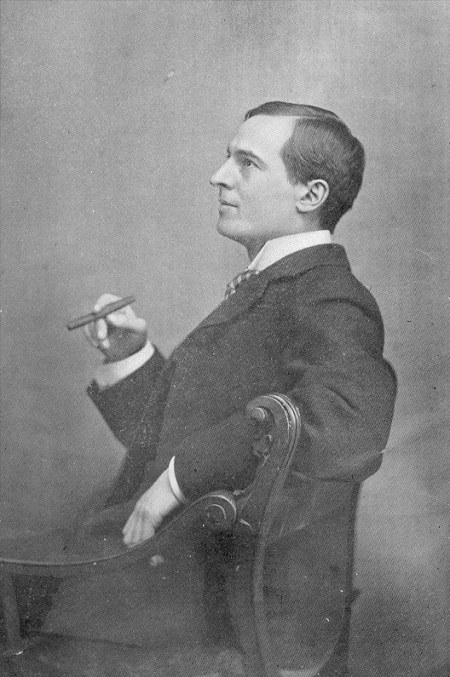

Harry Nelson Pillsbury followed in Morphy’s footsteps even more strikingly than did Mackenzie. Born in Massachusetts in 1872, he moved to New York in 1894 and quickly became the city’s leading player.

Harry Nelson Pillsbury

As it was with Morphy, Pillsbury’s brilliance so inspired confidence among his peers that the Brooklyn Chess Club financed his journey to Europe for him to play in the Hastings Tournament of 1895. With every great master of the day participating, the tournament was perhaps the strongest in history up to that point in time.

Hastings 1895 was Pillsbury’s first international tournament, but he won it unexpectedly. Scoring 16.5 points out of 21 rounds, he came ahead of Mikhail Chigorin, the world champion Emanuel Lasker, Tarrasch, and the ex-world champion Wilhelm Steinitz. His victory was a sensation in the United States, and he came home a celebrity.

Hastings 1895: Final standings after 21 rounds

Hastings 1895 marked Pillsbury as an elite player, and he was to place strongly in the coming powerful tournaments in the last few years of the 19th century. He came 3rd in St. Petersburg 1896 behind Lasker and Steinitz, and 4th in Nuremberg 1896 where he defeated Lasker, Chigorin and Tarrasch. He won Vienna 1898 jointly with Tarrasch. He placed joint 2nd-4th in London 1899 behind Lasker, and 2nd in Paris 1900, again, behind Lasker. He won Munich 1900 jointly with Geza Maroczy and Carl Schlechter.

Pillsbury was one of the few masters who could handle Lasker, and he fought him to a standstill, 5-5 with 4 draws. He was a rightful title contender, but, sadly, his star didn’t shine long, like Morphy’s. Sometime in his campaign, he was infected with syphilis, and he deteriorated physically and mentally until he passed away in 1906. It is one of the woeful stories of chess that his life was cut short, and the world championship match with Lasker failed to happen.

Finally, more than a century later, Robert Fischer emerged to replicate Morphy’s genius and feats closer than anyone ever did.

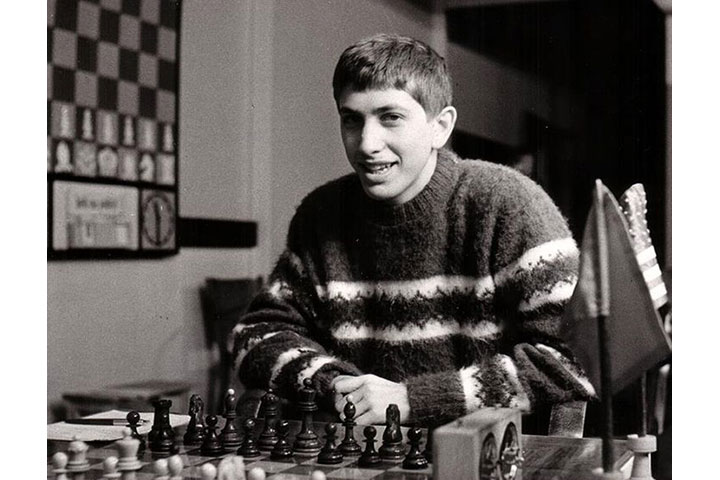

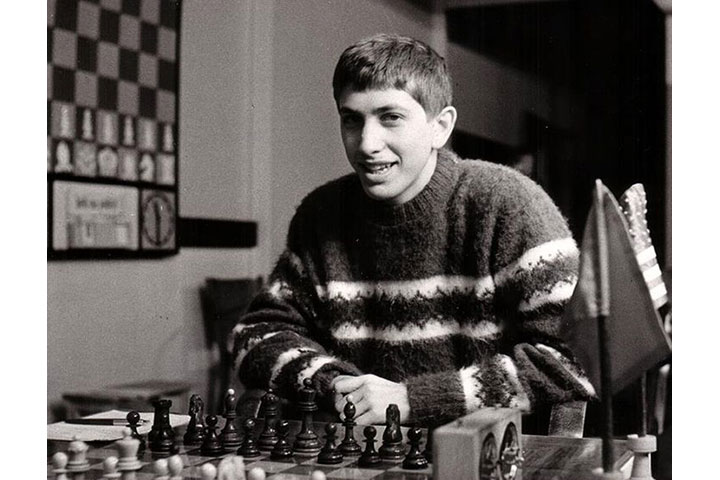

Bobby Fischer at the Interzonal Tournament Portoroz 1958 | Photo: Tournament book

Fischer’s life quite clearly parallels Morphy’s. A child prodigy himself, Fischer revealed his precocious talent when he defeated International Master Donald Byrne at about the same age as Morphy was when he beat Lowenthal. Their game that features a stunning Queen sacrifice has come to be known as “The Game of the Century.” It’s a well-known fact, also, that Fischer became a Grandmaster at 15, the youngest ever at that point in time.

Like Morphy, too, Fischer was unbeatable at home. He participated in eight US Championships, winning all of them. In the championship’s 1963 edition, particularly, Fischer swept a strong field that included Grandmasters Larry Evans, Pal Benko, Samuel Reshevsky, Arthur Bisguier and Robert Byrne, winning all of his eleven games. It is the only perfect score in the history of the US Championship.

Final Standings after round 11

Understandably, of course, Fischer’s rise to the top did not happen in a single “tour.” Competitive chess in Fischer’s time was already so organized that qualifications for the world championship had become a three-year cycle. The Soviets, moreover, had dominated world chess. They held the world title like a property, and they took all measures to keep it in their hands.

In the 1962 Curacao Candidates’ Tournament, Fischer could only finish fourth, 3.5 points behind the winner, Tigran Petrosian. Fischer accused the soviet delegation of Petrosian, Paul Keres, and Efim Geller of arranging their games, which convinced FIDE to drop the candidates’ tournament in favor of one-on-one, knock-out matches.

Five years after, Fischer was leading the 1967 Sousse Interzonal, but he withdrew due to differences with the organizers over the tournament’s schedule.

When Fischer hit full stride in the 1969-1972 cycle, however, his drive for the world championship was even arguably more brilliant than Morphy’s 1858 tour. Winning the 1970 Palma de Mallorca Interzonal by a 3.5 point margin, he proceeded to destroy Mark Taimanov and Bent Larsen in the knock-out matches, 6-0. He then dispatched Petrosian 6.5-2.5, before dethroning Boris Spassky in the 1972 World Championship Match, 12.5-8.5. Such domination had not been seen before or since.

In the last twist of fate, Fischer turned away from the game at the pinnacle of his powers. He also suffered the same mental instability that plagued Morphy in his final years.

Morphy has been aptly called “The Pride and Sorrow of Chess” for the extremes that his life came to. His genius and the similar talents of his successors have inspired wonder, and their games that are powerful and beautiful are a treasure. Their untimely loss, however, left chess less rich, and was nothing short of tragic.

Games

- Daniel Harrwitz vs. Paul Morphy – A surprisingly modern game from Morphy, which shows that he was more than just a Romantic player.

- George Henry Mackenzie vs. Wilhelm Steinitz – A sharp game where both sides have passed pawns. Steinitz seems to win the race to promote, but Mackenzie uncorks a combination that ends in mate.

- Harry Nelson Pillsbury vs. Isidor Gunsberg – Pillsbury plays a magical Knight ending against Gunsberg. With the victory, Pillsbury won Hastings 1895, the greatest triumph of his career.

- Boris Spassky vs. Robert Fischer – The most intense struggle of the 1972 world championship match. Fischer’s passed pawns prevail in the end against Spassky’s extra piece.

Links