Hidden diamonds

When you get a database such as Mega 2017, it is easy to just think of it as a monster database with millions of games (which it is), with tens of thousands of player photos (which it has), and tens of thousands of commented games (which it also has), but to stop there without a bit of digging is to miss out on a diamond mine to put all those in South Africa to shame.

It goes almost without saying that will you find within it games dating back to the 15th century, the birth of the modern game (in terms of rules), as well as all the games known thereafter. What you may not realize is that a huge number of these Golden Oldies not only come with annotations, but annotations that are by the players themselves or contemporaries. You will also find a significant number that can only be described as surprising!

Below is a small sample taken pretty much at random, with the exception that an effort was made to provide some variety in players and annotators. You will easily find thousands of others of similar quality.

Evergreen

Adolf Anderssen was a German master from the 19th century whose play was characterized by incredible imagination and derring-do. Although he famously lost important matches to Morphy and later Steinitz, he was easily one of the world’s greatest players of his age, and for nearly 30 years, from 1851 till his death in 1879, he won over half the tournaments he played in, ahead of top contemporaries.

Adolf Anderssen's preparations for the 1851 London International Tournament produced a surge in his playing strength: he played over 100 games in early 1851 against strong opponents.

His most famous games are the “Immortal Game” and the “Evergreen”, but needless to say many books could be made just of his tactical prowess. Below is a game against Carl Mayet, a match he played in 1851, with a breathtaking finish.

The notes are by the top Austrian born GM Eliskases, who later immigrated to Argentina at the onset of World War II.

Adolf Anderssen - Carl Mayet

(Annotations by Erich Eliskases)

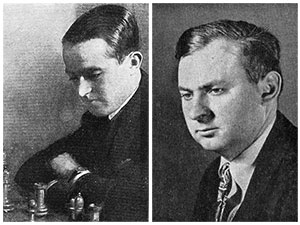

At first, the next game was simply chosen as an example of top players of the 30s with top commentators, but a little research showed its significant sporting importance in its day. The Czech player Salo Flohr and American player Reuben Fine were both in their prime in 1935/36, a period in which the two players really peaked, scoring important wins around the world so that they were considered top contenders for a World Championship match. Flohr tied for first with Botvinnik in Moscow 1935, and won Margate 1936 ahead of Capablanca among other notable results, while Fine raked in wins at Zanvoort 1936, ahead of World Champion Euwe, Tartakower, and Keres, plus a tie for first with Euwe at Amsterdam 1936, ahead of Alekhine.

|

|

|

|

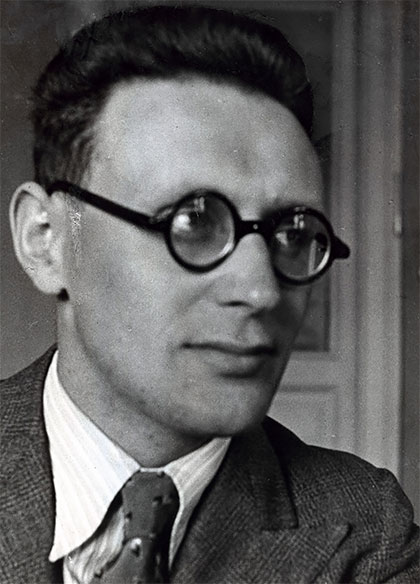

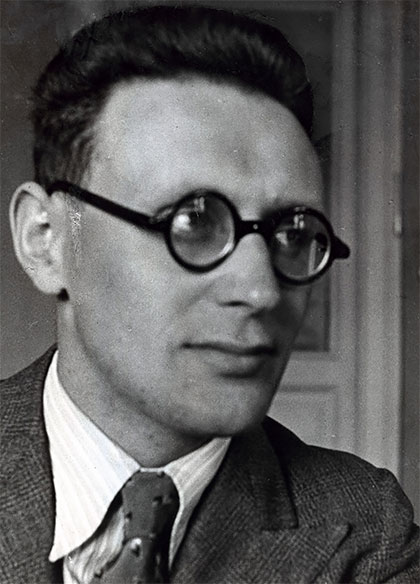

Salo Flohr (1933) |

Reuben Fine |

During this mutual period of unbridled success, the two competed at the famous Hastings tournament of 1935/36 where they met in the very first round. Little did they know that this first round game would ultimately decide the final standings. Reuben Fine won a fine victory, and eventually came first, whereas this was to be Flohr’s only loss, who came in second. Had they tied, they would have shared first on points.

Final standings at Hastings 1935/36

The sources for the annotations are given after the first move and are mouthwatering to say the least:

- Fine: Lessons From My Games.p.54-56.

- Schach-Echo 1936, S.17.

- Euwe in Schach-Echo 1936,S.38.

- Eliskases in WSZ 1936,S.11.

- Kotov:Think Like a Grandmaster.1971. p.21.

Salo Flohr - Reuben Fine

(Annotations by Fine/SE/Euwe/Eliskases/Kotov)

The third and last game shown was one that took serious deliberation due to the numerous attractive candidates initially separated for possible inclusion. The first was Paul Morphy vs Duke of Brunswick/Count Isouar, a rightly famous game, but with the unique annotations by Bobby Fischer! His notes are typically irreverent ("It's funny, I played two [simultaneous] exhibitions here in Sarajevo, and both players played exactly the same. Maybe they were trying to lose the same way, as a joke or something."). Another was Mikhail Botvinnik - David Bronstein (1951 match, G9) with notes by both players. Great stuff.

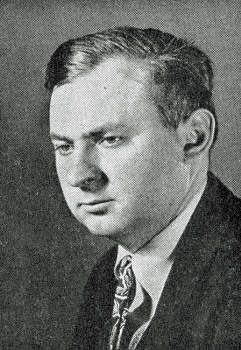

In the end, the following game was chosen for both its sporting, historical and (unintentional) humorous content. It highlights the 5th World Champion Mikhail Botvinnik during his ascension in a game against Vladimir Alatortsev at the 1932 Leningrad Championship. The game of course is excellent in and of itself, but the rich notes from various sources are what give it that extra shine. Botvinnik's notes from works published in both 1936 and later in 1984 show fascinating insight on his evolution and hindsight gained. This alone would warrant the price of entry as the comments are clearly identified per date.

Mikhail Botvinnik (1936)

However, the reader is also given the extensive and unforgiving annotations from Siegbert Tarrasch from his magazine Schachzeitung (Chess Newspaper) in late 1933. Although at the end of the game he decries the lack of brilliance displayed by Botvinnik, who he recognizes as a budding genius, but fails to see yet as a World Champion, he also brings about his famously instructive comments, which made classics of his works, quoted even by Kasparov to this day.

Siegbert Tarrasch was one of the foremost players of his day, as well as instructors. His work Three Hundred Chess Games is considered one of the great classics.

Botvinnikk - Alatortsev (Leningrad, 1932)

Position after 10.exd4

Tongue in cheek, Tarrasch writes:

"It is incomprehensible that Botvinnik — and everyone else, since the position has already occurred innumerable times — accepts an isolated pawn here, something which one usually fears almost as much a knight fork on the king and queen! But, joking apart, the teaching about how harmful the isolated queen's pawn is is one of the numerous wrong-headed ideas which this chess magazine was founded in order to contest."

Mikhail Botvinnik - Vladimir Alatortsev

(Annotations by Botvinnik [1936 and 1984] and Tarrasch)

As you can see, these are hardly the most famous games, as it would have been extremely easy to find notes in such cases, yet all bring enormous value to the user willing to look around for a hidden diamond. Mega 2017 is more than just a huge database described by large numbers, it is a an enormous library of classics just waiting for the student.