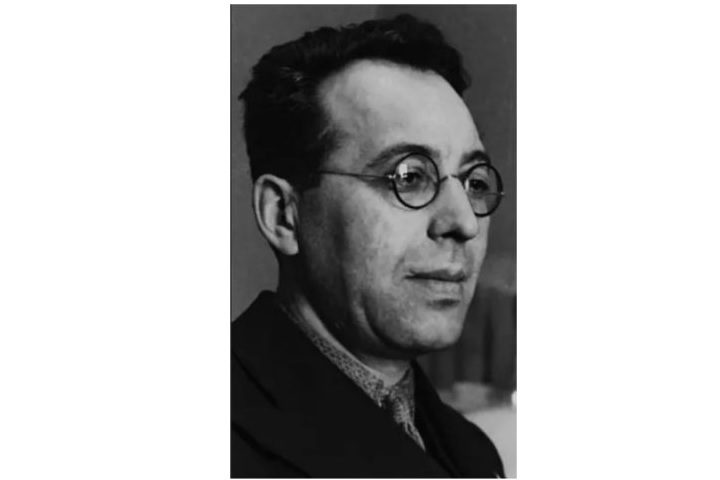

Grigory Levenfish was one of the brightest talents of pre-revolutionary Russia and the Soviet Union. A seemingly fateful life, however, denied him of the success and recognition that he deserved. Never a favorite of the Bolshevik chess authorities, he was deprived of competitive opportunities, yet became the Soviet champion twice.

Levenfish was born as Gershlik Levenfish on March 27, 1889 in the Polish town of Piotrkow, which was then part of the Russian Empire. His father, Yakov, was a businessman, while his mother, Golda, was a school teacher. Levenfish changed his name to Grigory only after his baptism in the Russian Orthodox Church in 1913.

When he was very young, Levenfish moved to Lublin with his mother, who settled with her sister. Levenfish had learned chess from his father at the age of six, but it was in Lublin that his interest in the game grew. His uncle was one of Lublin’s strongest players, and Mikhail Chigorin spent his last few years there.

Levenfish recounted how Chigorin's trips to Lublin to visit his wife and daughter stirred excitement in the city. The great master was already ill then and would pass away in 1908, but he was yet giving simultaneous exhibitions. Chigorin, whose opponents included Levenfish’s uncle, awed Levenfish with his brilliant play and post-game analysis.

After finishing school in Lublin in 1906, Levenfish went to the Technological Institute of St. Petersburg and took up Chemistry. The school boasted a strong chess circle, and among the ranks was V.O. Smyslov, the father of the future world champion, Vassily Smyslov. The stiff competition pushed Levenfish to improve rapidly. Playing for stakes, he recalled that he paid his strongest opponents a "frank" for a lesson, but soon the franks "flowed back from the other side."

When Levenfish was a student, the St. Petersburg Chess Assembly was formed. The club organized the Chigorin Memorial in 1909, the first international tournament in the city since the 1895 St. Petersburg Tournament. The tense matches between Emanuel Lasker, Akiba Rubinstein, Carl Schlechter and the other luminaries of the day all left a lasting impression on Levenfish.

The 1909 international tournament gave a boost to competitive chess in St. Petersburg. Tournaments and inter-city matches between St. Petersburg, Moscow, Łódź and Vilna were held. Levenfish, along with Pyotr Romanovsky and Alexander Alekhine, emerged as St. Petersburg's top players. In November of that year, Levenfish scored his first significant result when he won the St. Petersburg championship. Other successes followed in 1910, which brought him attention. In 1911, he was invited to his first international tournament in Carlsbad.

The participants of Carlsbad 1911. Levenfish is seated in the front row, second from left | Photo source: Douglas Griffin

The field in Carlsbad was exceptionally strong, with only Lasker and Siegbert Tarrasch missing among the world's top players. Levenfish finished in the lower half of the pack. His score of 11.5 out of 25, however, earned him the Master’s title in accordance with the regulations of the German Chess Union. He was unaware that his first appearance outside of Russia would be his last.

| # |

Player |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

21 |

22 |

23 |

24 |

25 |

26 |

Total |

| 1 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Germany_(1867–1918).svg.png) Richard Teichmann (German Empire) Richard Teichmann (German Empire) |

* |

1 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

18 |

| 2 |

Akiba Rubinstein (Russian Empire) Akiba Rubinstein (Russian Empire) |

0 |

* |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

17 |

| 3 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Carl Schlechter (Austria-Hungary) Carl Schlechter (Austria-Hungary) |

0 |

½ |

* |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

17 |

| 4 |

Gersz Rotlewi (Russian Empire) Gersz Rotlewi (Russian Empire) |

0 |

½ |

1 |

* |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

16 |

| 5 |

Frank James Marshall (United States) Frank James Marshall (United States) |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

* |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

15½ |

| 6 |

Aron Nimzowitsch (Russian Empire) Aron Nimzowitsch (Russian Empire) |

0 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

* |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

15½ |

| 7 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Milan Vidmar (Austria-Hungary) Milan Vidmar (Austria-Hungary) |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

* |

0 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

15½ |

| 8 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Germany_(1867–1918).svg.png) Paul Saladin Leonhardt (German Empire) Paul Saladin Leonhardt (German Empire) |

½ |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

* |

½ |

0 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

13½ |

| 9 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Savielly Tartakower (Austria-Hungary) Savielly Tartakower (Austria-Hungary) |

0 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

½ |

* |

1 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

13½ |

| 10 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Oldřich Duras (Austria-Hungary) Oldřich Duras (Austria-Hungary) |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

* |

0 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

1 |

13½ |

| 11 |

Alexandre Alekhine (Russian Empire) Alexandre Alekhine (Russian Empire) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

* |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

13½ |

| 12 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Rudolf Spielmann (Austria-Hungary) Rudolf Spielmann (Austria-Hungary) |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

* |

0 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

13 |

| 13 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Julius Perlis (Austria-Hungary) Julius Perlis (Austria-Hungary) |

½ |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

* |

½ |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

12 |

| 14 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Germany_(1867–1918).svg.png) Erich Cohn (German Empire) Erich Cohn (German Empire) |

½ |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

* |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

0 |

11½ |

| 15 |

Grigory Levenfish (Russian Empire) Grigory Levenfish (Russian Empire) |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

* |

1 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

11½ |

| 16 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Germany_(1867–1918).svg.png) Hugo Süchting (German Empire) Hugo Süchting (German Empire) |

0 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

0 |

* |

1 |

1 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11½ |

| 17 |

Amos Burn (United Kingdom) Amos Burn (United Kingdom) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

* |

0 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

| 18 |

Gersz Salwe (Russian Empire) Gersz Salwe (Russian Empire) |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

* |

1 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

½ |

11 |

| 19 |

.svg/16px-Flag_of_Switzerland_(Pantone).svg.png) Paul Johner (Switzerland) Paul Johner (Switzerland) |

½ |

0 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

* |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

10½ |

| 20 |

Abram Rabinovich (Russian Empire) Abram Rabinovich (Russian Empire) |

½ |

½ |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

* |

½ |

1 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

1 |

10½ |

| 21 |

.svg/23px-Flag_of_Austria-Hungary_(1867-1918).svg.png) Boris Kostić (Austria-Hungary) Boris Kostić (Austria-Hungary) |

0 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

½ |

½ |

0 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

½ |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

½ |

* |

½ |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

10½ |

| 22 |

Fyodor Duz-Khotimirsky (Russian Empire) Fyodor Duz-Khotimirsky (Russian Empire) |

0 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

½ |

* |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

10 |

| 23 |

Simon Alapin (Russian Empire) Simon Alapin (Russian Empire) |

½ |

0 |

½ |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

0 |

½ |

0 |

0 |

* |

½ |

½ |

0 |

8½ |

| 24 |

Oscar Chajes (United States) Oscar Chajes (United States) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

* |

0 |

1 |

8½ |

| 25 |

.svg/16px-Flag_of_Switzerland_(Pantone).svg.png) Hans Fahrni (Switzerland) Hans Fahrni (Switzerland) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

½ |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

* |

0 |

8½ |

| 26 |

Charles Jaffe (United States) Charles Jaffe (United States) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

½ |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

* |

8½ |

Levenfish participated in Vilna 1912 and placed joint 6th-7th with Alekhine. Rubinstein won the event, which was the fourth of the five international tournaments he would take that year. In a quadrangular tournament among Levenfish, Alekhine, Oldrich Duras, and Eugene Znosko-Borovsky in 1913, Levenfish finished joint first with Alekhine. In 1914, he entered the Master’s Tournament in St. Petersburg, which was a qualifying event for the great St. Petersburg International Tournament. Levenfish came in fifth place. Alekhine and Aron Nimzovitsch tied for first to advance to the grand tournament.

The second half of the decade was a tumultuous period for Europe and Russia. World War I broke out in 1914, and the Russian Revolution in 1917. These were dangerous and personally tragic times for Levenfish, and he would not resume competition until after 1920.

As a chemist, Levenfish was mobilized in the First World War in the Russian plants producing anti-agents to the deadly German gasses. In 1916, he and his wife Elena Vladimirovna lost their eldest daughter, Lida. In 1917, Elena, too, passed away. For much of the war and the revolution, he took care of his younger daughter Elena had left him behind. "It wasn’t even possible to think of chess," he said.

Apparently, Levenfish maintained his form, for he came back to win the Leningrad championships of 1922, 1924, and 1925 (St. Petersburg was renamed Petrograd during World War I, and then Leningrad in 1924). He also finished third in the Soviet Championship of 1920, and second in the championships of 1923 and 1925. In the Moscow international tournament of 1925, he ended only 15th, but defeated Lasker and drew the World Champion, Jose Raul Capablanca.

Between 1926 and 1933, Levenfish devoted himself to his profession. Gennady Sosonko recalls in his memoir that Levenfish initially believed that only the "giants of the game" were fit for professional chess. He became prominent in the glass industry, and came to be responsible for the design and construction of glasses produced by various glass factories. In 1933, however, a rail crash occurred, the cause of which was pinned on the glasses Levenfish designed. At the time, Soviet Russia was flexing its industrial might that offenses such as "sabotage" were punished harshly. For a moment, Levenfish’s fate hung in the balance. A report came out, however, that his design had been modified, and he was held faultless.

Shaken by the experience, Levenfish promptly gave up his career and turned chess professional. The results were immediate. In 1935, he became national champion when he finished joint first with Ilya Rabinovich in the 9th Soviet Championship in Leningrad. In 1937, he was once again national champion when he won the 10th Soviet Championship solely in Tbilisi. He also participated in the great Moscow international tournaments of 1935 and 1936. His performance in 1935 was stronger, and he finished in a tie for 6th place.

Soviet Championship, Leningrad 1935

When Levenfish turned professional, Mikhail Botvinnik was the rising star of Soviet chess. Botvinnik would cast a long shadow over Levenfish, who believed the Soviet authorities favored his rival in their drive for the world championship.

Soviet Championship 1937, Tbilisi 1937

The matter, of course, transcended the talents of the two great players. The Soviet Union had emerged out of class conflict, and the ruling Bolsheviks generally saw masters from pre-revolutionary Russia to belong to the opposing class. Levenfish, particularly, was regarded as part of the intelligentsia, that educated class of Russians who shaped the outlook and ideologies of old Russia. The Bolsheviks doubted their loyalties to the new state.

Other established masters similarly-placed as Levenfish, Alekhine and Efim Bogoljubov for instance, had foreseen a difficult future in the Soviet Union. They emigrated elsewhere, Alekhine settling in France and Bogoljubov in Germany.

Botvinnik, on the other hand, was purely Soviet by chess upbringing. As the strongest among the new breed of players, he embodied the intellectual qualities the Soviet state desired in its citizenry. The Bolsheviks saw him as their ideal representative.

Botvinnik and Levenfish had divided the last four Soviet championships between them, Botvinnik having won the 7th and 8th editions in 1931 and 1933. He was unable to compete in the championships that Levenfish won, as he was competing elsewhere in 1934 and was defending his thesis in 1937.

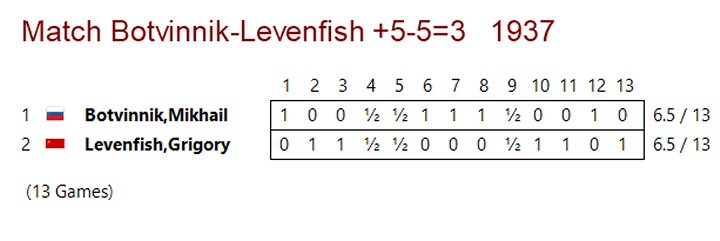

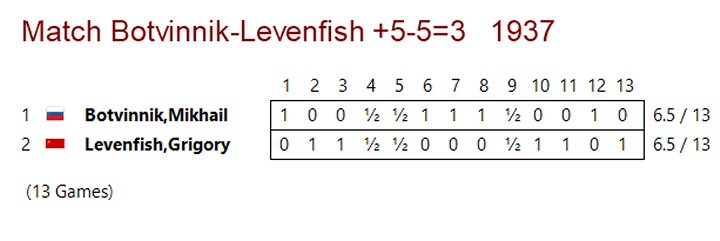

Levenfish claimed that Botvinnik challenged him to a match to settle the title of Soviet Champion. The match was to be a race to six, which would be declared drawn in the event of a stand-off at five. As the reigning champion, Levenfish was to be defending his title, and a successful defense would gain him the Soviet Grandmaster title.

.jpeg)

Levenfish vs Botvinnik | Photo source: Douglas Griffin

Levenfish led 2-1 after three games, but Botvinnik took games six, seven, and eight to lead 4-2. After a draw in game nine, Levenfish won three of the last four games to tie the score at five and leave the match drawn. Levenfish remained the Soviet champion and gained the Soviet Grandmaster title.

The match result would have entitled Levenfish to represent the Soviet Union in the next great international tournament, AVRO 1938. The Soviet authorities, however, gave the privilege to Botvinnik. Levenfish later described what he felt was his outright rejection:

"I considered that my victories in the ninth and tenth USSR Championships and the drawn result of match against Botvinnik gave me the right to participate in the AVRO-tournament. However, despite my hopes, I was not sent to this event.

My situation could be defined as a moral knock-out. All my efforts of the preceding years had been in vain. I felt confident in my powers, and would undoubtedly have fought honorably in the tournament."

In 11th and 12th Soviet championships, Levenfish performed relatively poorly. In 1940, he defeated Vladimir Alatortsev in a match, 5-2. When Germany under Adolf Hitler invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, he was once again called to patriotic duties. He was initially tasked with managing a glass factory in Penza before being relocated to the Industry Department in Kuibyshev. The journey to Kuibyshev was a harrowing one. Circumstances forced him to walk eighteen kilometers of open country in temperatures of -30C, which he was fortunate to survive. He later related that his health never fully recovered from his wartime experiences.

Levenfish returned to Leningrad after the war and became the main instructor in the city's Pioneer Palace. His students included Boris Spassky and Viktor Korchnoi. In 1946, he placed runner-up in the Leningrad championship. In 1949, at the age of 60, he participated in the Soviet championship for the last time. He was not expected among the top finishers, but defeated the winner, Vassily Smyslov.

Contemporaries of Levenfish remarked that the real cause of his isolation and disfavor among the Soviet authorities was his closed, uncommunicative, and even sarcastic nature. Consider, for instance, his criticism of Peter Saburov, the organizer of the 1914 St. Petersburg tournament:

"Unfortunately, the organization of the grandmaster tournament was entrusted to Saburov junior. This typical representative of the 'golden youth' of the aristocracy, incapable of any sort of work, had the idea of filling his leisure time with the organization of a chess tournament. Not having any understanding of chess, he decided that the tournament should be made up of strictly bureaucratic, formalistic features. Invitation was restricted to those players who had won first prize in an international tournament, although many of them had completely withdrawn from practical play, or had long ago lost their mastery of the game."

In the late 1940s, the chess writer Yakov Neishtadt found Levenfish living in Moscow, denied of his stipend as a grandmaster. "He lived in great poverty", Neishtadt recalled, "in a room with firewood heating in a communal flat. One could sometimes meet him in the Artists' Café opposite the Khudozhestvenny Theatre. Even here he stood out by his bearing, his manner, his way of speaking. He was very hard-up, but he never complained to anyone about anything."

Others who knew Levenfish very well, however, saw him as highly educated and cultured, a lover of the arts and music. Korchnoi once recalled him:

"I was fifteen years old. I can still remember that we looked at the Catalan. I can see him in the club at the card table playing vint, a Russian variation of bridge. He gave me the impression of being a very cultured man, witty and developed in all respects. I realized that this was a man from another world. When I got to know Botvinnik and began comparing, the comparison was not in favor of Botvinnik, who, next to Levenfish, seemed a shallow person, and whose humor was somehow petty. Botvinnik was a Soviet intellectual, who had it implanted, in contrast to Levenfish, who was an intellectual by blood and by pre-Revolutionary education. He saw things more broadly, thought differently, spoke foreign languages."

Spassky also spoke of his former teacher:

"He possessed an enormous natural talent, and he was an outstanding player. The fact that he was harsh, with a prickly tongue: well, how could he not be prickly, when Soviet life had practically destroyed him? But at heart he was responsive and very subtle."

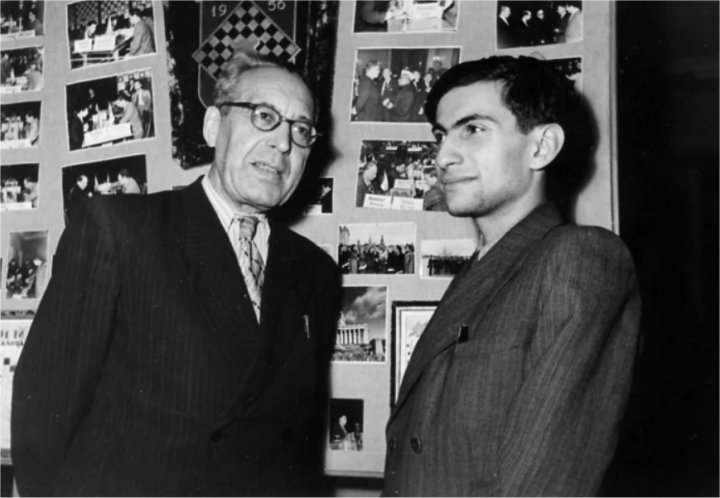

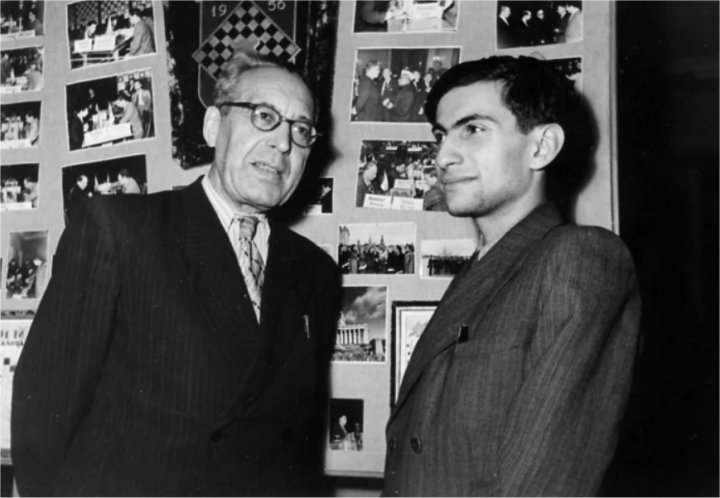

Levenfish and Mihail Tal in Moscow 1957 | Photo source: Douglas Griffin

In 1950, Levenfish was one of the Grandmasters FIDE named in its inaugural bestowal of the title.

When Levenfish passed away on February 9, 1961, Carlsbad 1911 remained as his sole appearance beyond the borders of the Soviet Union. For the close to fifty years that he competed at home, he amassed an impressive record against the world champions. Against Lasker, Euwe and Alekhine, he was equal. Against Capablanca, he was minus one. Against Smyslov, he was plus one. Against Botvinnik in more than twenty games, he was minus two. His crowning achievements, undoubtedly, were his two national titles and his drawn match with Botvinnik.

Levenfish also made significant contributions to the theory and literature of chess. As a theoretician, he has a variation of the Sicilian Dragon named after him. As a writer, he is known for the classic work he co-authored with Smyslov, Rook Endings. With Romanovsky, he co-authored a magnificent book on the 1927 World Championship Match between Capablanca and Alekhine. He produced a tournament book of the 9th USSR Championship that he won. Lastly, as though to leave a memory of his fate in Soviet Russia, he wrote an autobiography published posthumously that he entitled, Soviet Outcast.

Levenfish was an outstanding talent who was constrained by the social and political forces of his time. His achievements, regrettably, may have been short of his true capabilities.

References:

Levenfish, Grigory. Soviet Outcast. United Kingdom: Quality Chess UK Ltd, 2019.

Griffin, Douglas. (2017, January 19). Grigory Levenfish. https://dgriffinchess.wordpress.com/2017/01/19/grigory-levenfish/

Wikipedia. 2022. "Grigory Levenfish." Last modified October 3, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grigory_Levenfish

Games

Levenfish held his own against the World Champions. Here are some impressive victories against them:

Grigory Levenfish vs. Alexander Alekhine, All-Russian Masters Tournament, St. Petersburg, 1914.

Emanuel Lasker vs. Grigory Levenfish, Moscow International Tournament, 1935.

Grigory Levenfish vs. Mikhail Botvinnik, Game 2, Match, Moscow/Leningrad, 1937.

Grigory Levenfish vs. Vassily Smyslov, USSR championship, Moscow 1949.

Finally, a fine positional game involving the motifs of a better Bishop, and the active King.

Vladimir Alatortsev vs. Grigory Levenfish, 10th USSR Championship, Tbilisi, Georgia, 1937.

Levenfish vs Alatortsev, Leningrad 1940 | Photo source: Douglas Griffin

Links

See more articles by Eugene Manlapao...

.jpeg)