Unsolved Chess Mysteries (20)

By Edward Winter

Hallucinations

C.N. 2557 commented on our inability to find game-scores which fit in with

the following report, taken from page 315 of the Chess Amateur, July

1908:

‘Referring to “hallucinations that occur in match and tournament

play”, Mr Bruno Siegheim mentions in the Johannesburg Sunday Times

that in one of the games of the Blackburne-Steinitz match, a check which could

have won a rook was left on for several moves. The possibility was seen by

everyone present in the room except the two players. Mr Siegheim adds that

a still more curious incident occurred at Breslau, in an Alapin-Blackburne

game. Mr Blackburne checkmated his opponent, but assuming that Herr Alapin

would see the mate, Mr Blackburne did not announce it. Herr Alapin looked

at the position intently, trying to find a move, and the spectators smiled

and whispered. At the end of five minutes Mr Blackburne relieved his opponent’s

anxiety by informing him that he had been checkmated.’

Can readers offer suggestions regarding these alleged games?

Queen sacrifice missed?

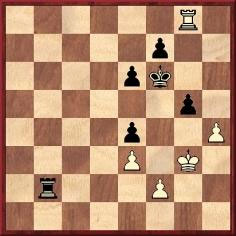

The game-score below, from a simultaneous display, was presented in C.N. 2562.

It had appeared (without notes) on page 154 of Schachjahrbuch 1914 I. Teil

by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914), but we wonder if it is correct, given that,

at move 23, White could have forced mate with a standard queen sacrifice.

Joseph Henry Blackburne – E.S.

St Petersburg, 9 May 1914

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Nc6 4 d3 Be7 5 f4 exf4 6 Bxf4 Na5 7 Nf3 Nxc4 8 dxc4

d6 9 O-O Bg4 10 Qe1 Nh5 11 Be3 O-O 12 Nd5 a6 13 Rd1 c6 14 Bb6 Qd7 15 Ne3 Bxf3

16 Rxf3 Qe6 17 Nf5 Rae8 18 Bd4 Nf6 19 Qg3 g6 20 Nxe7+ Qxe7 21 Bxf6 Qxe4 22 Qh3

Re6

23 Bc3 f6 24 Re1 Resigns.

Fischer v Collins in the 1970s

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) drew attention in C.N. 4688 to the

following passage about Bobby Fischer on page 483 of ‘Garry Kasparov

on Fischer My Great Predecessors Part IV with the participation of Dmitry

Plisetsky’ (London, 2004):

‘In 1977 he easily defeated a computer at the Massachusetts Institute

of Technology (3-0), and he crushed his teacher Collins in a training match

(+16 –1 =3).’

Our correspondent asked what is known about this ‘training match’

against John W. Collins (1912-2001), and the question remains open.

Pillsbury’s brain

In C.N. 2405 John S. Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) wrote:

‘Elmer Ernest Southard (1876-1920) played chess for Harvard University

for four years, participating in the annual Princeton-Harvard-Yale-Columbia

Intercollegiate chess tournaments during 1895-1899. He annually dominated

play in these events, finishing his college career with a record 22-2 result.

Southard’s distinguished professional career was cut short on 8 February

1920, when he died of pneumonia at the age of 43. His son, Ordway Southard,

continued the association with chess, publishing Leaves of Chess a journal

of scaccography from January 1957 through 1961.

In researching Elmer Southard’s chess career, I obtained his obituary

in the New York Times for 9 February 1920. There we learn that Southard

was “a member of the St. Botolph and Boston Chess Clubs, and noted

as one of the foremost amateur chess players in America. Dr Southard was particularly

interested in the case of Harry N. Pillsbury, the former American champion

chess player, who in the later years of his life lost his mind. Dr Southard

made an examination and study of the brain of Pillsbury in an attempt to decide

the mooted question of whether a genius for chess tends to deteriorate the

mind.”

Had Dr Southard been a Freudian psychoanalyst, his examination of Pillsbury’s

“brain” might well be written off as poor word choice by the Times

writer responsible for the obituary. At the time of his death, though,

he happened to be Bullard Professor of Neuropathology at Harvard Medical School,

as well as pathologist to the Massachusetts Commission on Mental Diseases

and a Director of the Massachusetts Psychiatric Institution. It appears that

Pillsbury’s brain may actually have been in his hands.

Does anyone know if Dr Southard’s study of Pillsbury’s brain

has survived, perhaps in the vast depths of Harvard’s libraries? Has

anyone else seen Pillsbury’s brain?’

Information about the master’s period in hospital is available in our

feature article Pillsbury’s

Torment.

Below, from our collection, is an envelope handwritten by Pillsbury in 1899:

Switched envelopes

C.N. 4404 quoted the following from page 51 of A. Alekhine Agony of a Chess

Genius by P. Morán (Jefferson, 1989):

‘The 1942 “switched envelopes” anecdote best illustrates

Alekhine’s patriotism: he mailed a pro-Communist letter to the Third

Reich, and a pro-Nazi letter to the USSR.’

How far back can this story be traced?

Bonjour Blanc

Bonjour Blanc by Ian Thomson (London, 2004, but originally published

in 1992) is subtitled ‘A Journey through Haiti’, and the publicity

material stated that ‘a Swiss chess champion’ was one of the ‘lively

gallery of eccentrics’ encountered by the author. He is named as Gottfried

Kraüchi, and a brief sample passage from page 70 is reproduced below:

For Kraüchi read Kräuchi. The term ‘a Schweiz-Deutsch’ is

peculiar, and, as mentioned in C.N. 4939, we can vouch for none of the other

information, except that he was indeed listed as the Haitian delegate on page

v of FIDE’s minutes of the 1988 Congress in Thessaloniki. His name appeared

there as ‘Gottfied, Krauchi’ (sic). Do readers know any more

about him?

‘99% tactics’

‘Chess is 99% tactics’ is a famous quotation, usually ascribed

to Richard Teichmann. The best corroboration we can offer for it was given in

C.N. 2307, from page 134 of volume 4 of Schachtaktik by E. Voellmy (Basle,

1930):

‘Zu meinem Trost hat der grosse Meister und Lehrer Teichmann mir

vor Jahren in Zürich auseinandergesetzt (wobei er leicht übertrieb): “Das

Schach besteht zu 99% aus Taktik”.’

C.N. 2339 gave a quote from page 3 of Reuben Fine’s book The Middle

Game in Chess (New York, 1952):

‘Among players of equal strength, it is always the last blunder, and

the ability to see it, that determines who will win. At every level of chess

skill, including the world championship class, it is still true that tactics

is 99 per cent of the game.’

As noted on page 342 of A Chess Omnibus, many variations of the remark

have been seen. For instance, on page 137 of the July 1955 Chess World

C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘Kostić once said chess was 90% tactics, and he was right –

not necessarily in the precise figure but in the general idea it conveys.’

‘Edward Young’

C.N. 5014 mentioned the continuing search for information about ‘Edward

Young’ (see page 327 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves). Books and

articles appeared under that name, but page 659 of Douglas A. Betts’ volume

Chess An Annotated Bibliography of Works Published in the English Language

1850-1968 (Boston, 1974) stated that ‘Edward Young’ was a pseudonym

for Fred Reinfeld.

The first appearance of the name that we have found is on page 114 of Chess

Review, April 1955, at the start of a two-page article:

The two volumes below have the same contents and were published in 1960 by,

respectively, Arco Publications, London and Castle Books, USA:

Does solid proof exist that Fred Reinfeld was ‘Edward Young’?

Capablanca v Fine

C.N. 2907 (see pages 230-231 of Chess Facts and Fables) discussed this

position, with White to move, from Capablanca v Fine, AVRO, 1938:

The Cuban played 40 Rxg5, and the game was drawn after 40...Rb4 41 Kh3 e5 42

Rg1. However, 40 h5 would have won. C.N. 593 mentioned that 40 h5 had been commented

upon by Wolfgang Heidenfeld on page 8 of his book Draw! (London, 1982).

The missed win, wrote Heidenfeld, ‘was pointed out a good 20 years later

by Paul Schlensker in Schach-Echo’. Thanks to a lead from another

correspondent, Paul Timson (Whalley, England), we were subsequently able to

show (in C.N. 1475) that 40 h5 had been given as early as 1951, by Gerald Abrahams.

He published the game on pages 254-256 of his book Teach Yourself Chess,

and in the original edition (1948) he wrote:

‘40 RxP. Leaving Black with a “cut-off” king.’

In the Revised Edition of 1951 this was amended to:

‘40 RxP. P-R5 appears to win easily. If 40…R-Kt8 41 K-Kt2, etc.’

Also in C.N. 1475 the Dutch librarian Rob Verhoeven informed us that a search

at the Royal Library in The Hague had failed to locate where in Schach-Echo

Paul Schlensker had indicated the winning move. That question remains open

today. However, unless Heidenfeld’s words ‘a good 20 years later’

regarding Schach-Echo were a mistake, Abrahams gave 40 h5 much earlier

than did Schlensker.

Was Abrahams the first to point out 40 h5 in print?

Submit information

or suggestions on chess mysteries

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around

5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Edward

Winter is the editor of Chess

Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados

to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then around

5,000 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by

Winter: Chess

Explorations (1996), Kings,

Commoners and Knaves (1999), A

Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess

Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph

on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing

in its archives

will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes

and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from

around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary

readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent

masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess

History Center.

Articles by Edward Winter

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (1)

14.02.2007 – Since Chess

Notes began, over 25 years ago, hundreds of mysteries and puzzles have

been discussed, with many of them being settled satisfactorily, often thanks

to readers. Some matters, though, have remained stubbornly unsolvable –

at least so far – and a selection of these is presented here. Readers are

invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (2)

12.03.2007 – We bring you a further selection

of intriguing chess mysteries from Chess

Notes, including the origins of the Marshall Gambit, a game ascribed

to both Steinitz and Pillsbury and the bizarre affair of an alleged blunder

by Capablanca in Chess Fundamentals. Once again our readers are invited

to join the hunt

for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (3)

27.03.2007 – Recently-discovered photographs

from one of Alekhine’s last tournaments, in Spain in 1945, are proving baffling.

Do they show that a 15-move brilliancy commonly attributed to Alekhine is

spurious? And do they disprove claims that another of his opponents was

an 11-year-old boy? Chess

Notes investigates, and once again our readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (4)

10.04.2007 – What would have happened if the

score of the 1927 Capablanca v Alekhine match had reached 5-5? Would the

contest have been declared drawn? The affair has been examined in depth

in Chess Notes.

Here chess historian Edward Winter sifts and summarizes the key evidence.

There is also the strange case of a fake photograph of the two masters.

Join

the investigation.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (5)

30.04.2007 – We bring you a further selection

of mysteries from Edward Winter’s Chess

Notes, including an alleged game by Stalin, some unexplained words attributed

to Morphy, a chess magazine of which no copy can be found, a US champion

whose complete name is uncertain, and another champion who has vanished

without trace. Our readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (6)

19.05.2007 – A further miscellany of mysteries

from Chess Notes is presented

by the chess historian Edward Winter. They include an alleged tournament

game in which Black was mated at move three, the unclear circumstances of

a master’s suicide, a chess figure who was apparently unaware of his year

of birth, the book allegedly found beside Alekhine’s body in 1946, and the

chess notes of the poet Rupert Brooke. Join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (7)

02.06.2007 – The chess historian Edward Winter

presents another selection of mysteries from Chess Notes. They include an

alleged game by Albert Einstein, the origin of the Trompowsky Opening, the

termination of the 1984-85 world championship match, and the Marshall brilliancy

which supposedly prompted a shower of gold coins. Readers are invited to

join in the hunt

for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (8)

In this further selection from Chess

Notes historian Edward Winter examines some unauthenticated quotes,

the Breyer Defence to the Ruy López, the origins of the Dragon Variation,

the contradictory evidence about a nineteenth century brilliancy, and the

alleged 1,000-board exhibition by an unknown player. Can our readers help

to solve these new

chess mysteries?

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (9)

Why did Reuben Fine withdraw from the 1948 world championship?

Did Capablanca lose an 11-move game to Mary Bain? Was Staunton criticized

by Morphy for playing ‘some devilish bad games’? Did Alekhine

play Najdorf blindfold? Was Tartakower a parachutist? These and other mysteries

from Chess

Notes are discussed by Edward Winter. Readers are invited to join in

the hunt

for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (10)

15.07.2007 – Did Tsar Nicholas II award the ‘grandmaster’

title to the five finalists of St Petersburg, 1914? What connection exists

between the Morphy family and Murphy beer? Can the full score of one of

Pillsbury’s most famous brilliancies be found? Did a 1940s game repeat

a position composed 1,000 years previously? Edward Winter, the Editor of

Chess

Notes, presents new

mysteries for us to solve.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (11)

01.08.2007 – Did Alekhine attempt suicide in 1922? Why is

1 b4 often called the Hunt Opening? What are the origins of the chess proverb

about the gnat and the elephant? Who was the unidentified figure wrongly

labelled Capablanca by a chess magazine? Does Gone with the Wind

include music composed by a chess theoretician? These and other mysteries

from Chess Notes

are discussed by the historian Edward Winter. Readers are invited to join

the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (12)

12.08.2007 – This new selection from Chess

Notes focuses on José Raúl Capablanca (1888-1942). The chess historian

Edward Winter, who wrote a book about the Cuban genius in the 1980s (published

by McFarland), discusses a miscellany of unresolved matters about him, including

games, quotes, stories and photographs. Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (13)

26.08.2007 – In a 1937 game did Alekhine play two moves in succession?

Can the full score of a Nimzowitsch brilliancy be found? Who was Colonel

Moreau? Why was it claimed that Morphy killed himself? Who were the first

masters to be filmed? What happened in the famous Ed. Lasker v Thomas game?

Is a portrait of the young Philidor genuine? From Chess

Notes comes a new selection of mysteries

to solve.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (14)

The latest selection from Chess

Notes consists of ten positions, including fragments from games ascribed

to Capablanca and Nimzowitsch. Was an alleged Bernstein victory a composition?

What is known about a position in which Black resigned despite having an

immediate win? Can more be discovered about the classic Fahrni pawn ending?

Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (15)

Chess books repackaged as camouflage in Nazi Germany. Numerous contradictions

regarding a four-move game. The chess encyclopaedia that never was. Quotes

strangely attributed to Spielmann and Capablanca. These and other mysteries

are discussed in the latest selection from Chess

Notes. Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (16)

Did Lasker invent a tank? Why did Mieses complain to FIDE about Bogoljubow?

What merchandising carried Flohr’s name? Who coined the term ‘grandmaster

draw’? What did Hans Frank write about Alekhine? Did Tom Thumb play

chess? These are just some of the questions discussed in the latest selection

from Chess Notes.

Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (17)

This further selection from Chess

Notes examines some gross examples of fraud and plagiarism in chess

literature. A number of books, for instance, have been published in Canada

and India under the names of Brian Drew, Frank Eagan, Thomas E. Kean and

Philip Robar, but did any of those individuals even exist? Readers are invited

to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (18)

An apparent missed mate in one at the 1936 Munich Olympiad; an

enigma regarding two Fox brilliancies; the origins of the Swiss System;

an untraceable painting of Staunton; the strange case of the prodigy Birdie

Reeve. These and other mysteries are discussed in a further selection from

Chess Notes.

Readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

-

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (19)

18.11.2007 – A further selection from Chess

Notes focuses on games and positions. Why is it claimed that Rubinstein

played an ending that repeated a nineteenth-century composition? Did Chigorin

remove one of his own pieces from the board in an endgame against Tarrasch?

And what about the game which Fahrni purportedly won by moving his remaining

pawn backwards? Join

in the hunt for clues.

-

Edward Winter presents: Unsolved Chess Mysteries (20)

After Pillsbury died, did a chessplayer examine his brain? Was Edward Young

a pseudonym used by Fred Reinfeld? Did Blackburne overlook a standard queen

sacrifice? Who discovered Capablanca’s missed win against Fine at

AVRO, 1938? Did Fischer play a training match in the 1970s against Collins?

On these and other matters from Chess

Notes readers are invited to join

in the hunt for clues.

Edward

Winter is the editor of

Edward

Winter is the editor of