Over 1,100 special theoretical databases, 180 new opening surveys, a large number revised — in total 6,680 surveys — and over 38,000 illustrative games.

Early chess players recognized that a typical game could be divided into three parts, each with its own character and priorities: the opening stage, when a player develops the pieces from their starting squares; a middlegame stage, in which plans are conceived and carried out; and an endgame stage, following several exchanges and captures, in which the player with the superior chances tries to convert an advantage into victory.

Books analyzing a few basic opening moves, elementary middlegame combinations, and simple elements of endgame technique appeared as early as the 15th century. About 1620 an Italian master, Gioacchino Greco, wrote an analysis of a series of composed games that illustrated two contrasting approaches to chess. Those games pit a material-minded player, who attempts to win as many of the opponent’s pieces as possible, against an opponent who sacrifices material in pursuit of checkmate—and usually wins. Greco, regarded as the first chess professional, emphasized tactics. His games were filled with pretty combinations made possible by poor defensive play. They had considerable influence in popularizing chess and in showing that there were different theories about how it should be played.

Chess Endgames 1 - Basic knowledge for beginners

Endgame theory constitutes the foundation of chess. You realize this in striking clarity once you obtain a won endgame but in the end have to be content with a draw in the end because of a lack of necessary know-how. Such accidents can only be prevented by building up a solid endgame technique. This is Karsten Müller‘s fi rst DVD and the grandmaster from Hamburg and endgame expert, here lays the foundation for acquiring such a technique. The fi rst part of his training series can be started without any endgame knowledge, only a knowledge of the rules of chess is assumed.

The first coordinated explanation of how chess games are won came in the 18th century from François-André Philidor of France. Philidor, a composer of music, was regarded as the world’s best chess player for nearly 50 years. In 1749 Philidor wrote and published L’Analyze des échecs (Chess Analyzed), an enormously influential book that appeared in more than 100 editions.

The first coordinated explanation of how chess games are won came in the 18th century from François-André Philidor of France. Philidor, a composer of music, was regarded as the world’s best chess player for nearly 50 years. In 1749 Philidor wrote and published L’Analyze des échecs (Chess Analyzed), an enormously influential book that appeared in more than 100 editions.

In Analyze Philidor used apparently fictitious games to illustrate his principles for conducting a strategic, rather than tactical, battle. His comments on certain 1.e4 e5 openings were copied for decades by other masters, and his analysis of king, rook, and bishop against king and rook was the first extensive examination of a particular endgame. But it was Philidor’s middlegame advice that was his greatest legacy. He emphasized the role of planning: Once all a player’s pieces are developed, that player should try to form an overall goal, such as kingside attack, that coordinates the forces. Philidor also placed a premium on anticipating enemy threats rather than merely concentrating on one’s own attack.

Greco and previous writers had explored the tactical interplay of two or three pieces. But Philidor believed that the significance of the pawns had been overlooked and drew particular attention to their weaknesses and strengths. His most famous comment — that “pawns are the very life of the game” — is often cited without his explanation of why they are important: because, he said, pawns alone form the basis for attack.

Know the Terrain Vol. 5: The Philidor Structure

The Philidor structure (White pawns on d4 and e4, Black pawns on d6 and e5), is a fundamental position in the open games. In his new training course, IM Sam Collins shows you just how much explosive power is packed into this apparently simple structure.

Philidor believed that a mobile mass of pawns is the most important positional factor in the middlegame and that an attack will fail unless the pawns to sustain it are properly supported. He warned against allowing pawns to be isolated from one another, doubled on the same file, or made backward — that is, unguarded by another pawn and incapable of being safely advanced. He linked the qualities of pawns to other pieces and was the first to emphasize how a bishop could be bad or good depending on how restricted it was by a fixed pawn structure. He also advocated the exchange of an f-pawn for an enemy e-pawn because it would partially open the file for a castled rook at f1. While previous authors had shown how pawns or other pieces could be temporarily sacrificed in checkmating or material-gaining combinations, Philidor illustrated the purely positional sacrifice in which a player obtains compensation such as superior piece mobility or pawn structure.

Philidor believed that a mobile mass of pawns is the most important positional factor in the middlegame and that an attack will fail unless the pawns to sustain it are properly supported. He warned against allowing pawns to be isolated from one another, doubled on the same file, or made backward — that is, unguarded by another pawn and incapable of being safely advanced. He linked the qualities of pawns to other pieces and was the first to emphasize how a bishop could be bad or good depending on how restricted it was by a fixed pawn structure. He also advocated the exchange of an f-pawn for an enemy e-pawn because it would partially open the file for a castled rook at f1. While previous authors had shown how pawns or other pieces could be temporarily sacrificed in checkmating or material-gaining combinations, Philidor illustrated the purely positional sacrifice in which a player obtains compensation such as superior piece mobility or pawn structure.

First Steps in Gambits and Sacrifices by IM Andrew Martin

Gambit play and the joy of sacrificing is an important part of the improving process. In order to become a strong player you must learn to attack and make combinations. Many continue to play in an aggressive style throughout an entire chess lifetime!

From 1750 to 1769 a group of masters from Modena, Italy — Ercole del Rio, Giambattista Lolli, and Domenico Ponziani — criticized Philidor’s ideas. They believed that he had exaggerated the importance of the pawns at the expense of the other pieces and had minimized the power of a direct attack on the enemy king. By analyzing the play of 16th-century Italian masters, the Modena school showed that games could be won in fewer than 20 moves through speedy piece mobilization, compared with Philidor’s slow-developing pawn marches.

There followed a proliferation of speculative pawn sacrifices in the opening, called gambits, in order to achieve rapid mobilization and open lines for an attack. Checkmating attacks, often with startling sacrifices in concluding combinations, became the hallmark of many players of the 19th century. These leading masters were described as members of the Romantic school of chess.

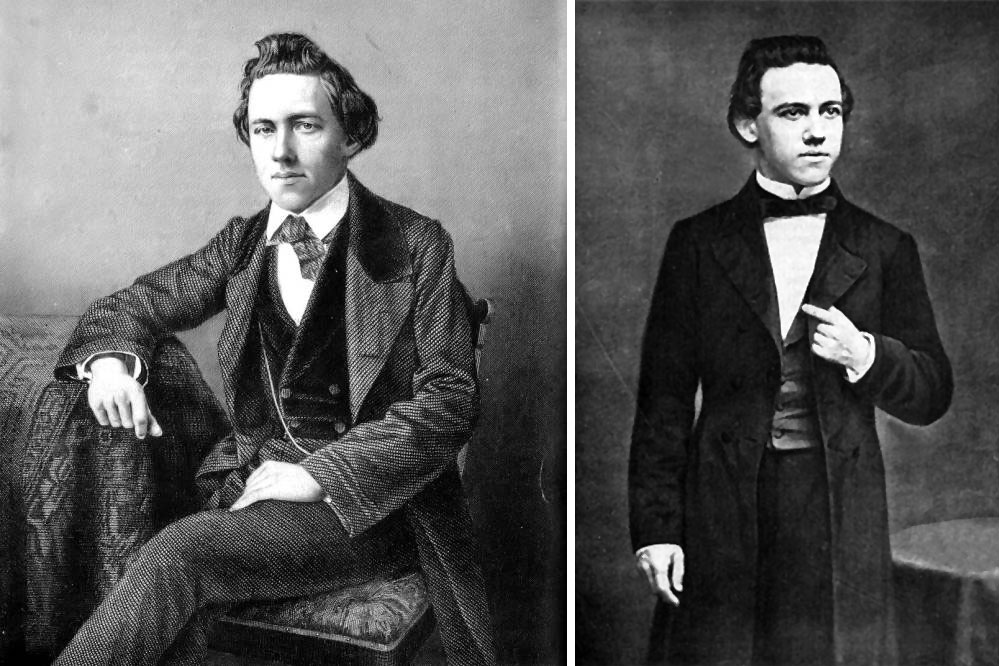

The ideas of the Modena school were not fully appreciated until they appeared, in slightly different form, in the games of Paul Morphy, the first American recognized as the world’s best player. Morphy’s chess career lasted less than three years and consisted of fewer than 75 serious games. In 1858–59 he defeated all the leading European players, with the disappointing exception of Howard Staunton, who evaded all attempts to arrange a match. At the age of 22 Morphy retired from serious chess. Morphy remains the only great chess thinker who left no written legacy.

Morphy’s contemporaries knew as much about the openings as he did, and some of them could calculate combinations as well as he. But Morphy understood how and when to attack better than anyone else. This enabled him not only to win favourable positions but also to avoid loss in inferior positions. After he defeated Adolf Anderssen, the greatest of the Romantics, by a lopsided score of 7–2, a supporter asked Anderssen why he had not sacrificed his pieces brilliantly against the American, as he had against other masters. “Morphy won’t let me,” Anderssen is reputed to have replied.

Morphy appreciated that superior development—getting pieces onto good squares in the first 10 to 15 moves—was relatively unimportant in the semiclosed, blocked pawn structures that Philidor had embraced. But, as the centre or kingside became more open, an advantage in development increased in value. In Morphy’s best-known games, pawns and knights played minor roles. Pawns were often sacrificed so that the queen, rooks, and bishops could join the attack as soon as possible. The first priority for Morphy was the initiative, the ability to force matters. Superior development in a position with few centre pawns conferred the initiative on one player. In the games of lesser players the initiative might pass back and forth as players err. But Morphy rarely failed to bring an initiative to fruition.

Left: Engraving by Daniel John Pound, based off a photograph by a Parisian photographer named Thompson) was first published in "The Drawing-Room Portrait Gallery of Eminent Personages," vol. II, London. 1859 | Right: Morphy in New York City, 1857 by Mathew Brady

Master Class Vol.9: Paul Morphy

Learn about one of the greatest geniuses in the history of chess! Paul Morphy's career (1837-1884) lasted only a few years and yet he managed to defeat the best chess players of his time.

Read the full chess article at Britannica.com

Part 2 will follow shortly with a look at Wilhelm Steinitz and the Classical era...