Encourage them to stay

The following article is reproduced by very kind permission of the writer, David Smerdon. The original can be found here.

Summary: Female Participation rates are higher in countries that are traditionally patriarchal. Various theories are discussed. Federations seeking to boost female participation should concentrate on teaching chess to girls in or before primary school, as well as encouraging young adult women to stay in the chess world.

Here’s a quiz for you. Try to guess which of these countries have the highest percentage of female chess players:

- Brazil, China, Denmark, France, Germany, India, Indonesia, Iran, Kenya, Mexico, Netherlands, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom, USA, Vietnam

We’ll get to the answer soon, but it’s an indisputable fact that chess is a man’s game – at least statistically. All players know only too well the feeling of walking into a club to see twenty or even more men for every woman. It’s not even that uncommon to play a tournament with no females at all. How can such a ‘fair’ sport that purports to provide a level playing field for people of all colours, races, ages and genders end up with so few of the fairer sex?

One of the most common questions that a chess player might hear from non-players is “Why are there women-only tournaments?” This is just one of the ideas chess organisers have come up with to address female participation; another is having special female titles, such as ‘Women’s Grand Master’, which has lower standards than the male (‘Open’) equivalent. Special female prizes are regular features in tournaments, though this measure can occasionally still not be enough. At the end of a recent State championship in Australia, where the highest-performing female is usually awarded the State women’s title, the organisers faced a dilemma as to what to do with the sole female participant. The young girl had put in a fabulous performance, but ultimately did not get the title on account of not having any female competitors.

The London System PowerBase 2019 contains 9105 games of which 113 are annotated.

The London System PowerBase 2019 contains 9105 games of which 113 are annotated.

Top female player Hou Yifan famously rejected to play in the women's world championship cycle | Photo: Alina l'Ami

You are probably not surprised to hear that female participation rates differ across the world. After all, some cultures value girls differently to boys. Some countries may be more supportive of women playing competitive games against men. In more conservative countries, a girl might be encouraged to get married and stay at home with the kids, rather than play rated tournaments. In poorer countries, a family might not be able to afford to send all of the children to chess lessons, and so the girls might miss out.

These are all intuitive stories. And indeed, female participation rates do vary significantly, and predictably, across the world. But not in the way you might expect. Going back to the countries in the quiz at the beginning, I suspect most people would arrange them in roughly the same order as their level of gender equality. The United Nations Development Programme releases a ranking of gender equality every year, and using the latest figures, those 16 countries are ranked like this:

- Denmark

- Sweden

- Netherlands

- Germany

- France

- United Kingdom

- China

- USA

- Vietnam

- Mexico

- South Africa

- Brazil

- Indonesia

- Iran

- India

- Kenya

Seems logical enough, right? Here’s a graph of many more countries, ranked by the UN’s gender equality index:

Click or tap any image to enlarge to full size!

You can see the usual suspects at the top end of the scale: Switzerland, the Netherlands, and all of Scandinavia, as well as most of western Europe. At the other end we mainly find developing countries or other nations in the Middle East and the subcontinent. I’ve dropped countries with a very small number of Fide-rated chess players, because I want to compare this to gender participation rates. If the intuition above holds, then we would expect to see similarly downward-sloping bars when we add in the female participation rates: Higher rates in Scandinavian countries than in typically patriarchal Islamic nations, for example. So let’s see. Thanks to some data from the indefatigable Jeff Sonas, I was able to match up a country’s proportion of females among active, Fide-rated chess players against its gender equality score. The data below covers 1999-2015, but I also checked against a recent sample from November 2018 and the pattern is the same. Remember, for the stories above to be true, we’re expecting the the bars to get lower as we move from left to right. Here’s the actual result:

You can see the usual suspects at the top end of the scale: Switzerland, the Netherlands, and all of Scandinavia, as well as most of western Europe. At the other end we mainly find developing countries or other nations in the Middle East and the subcontinent. I’ve dropped countries with a very small number of Fide-rated chess players, because I want to compare this to gender participation rates. If the intuition above holds, then we would expect to see similarly downward-sloping bars when we add in the female participation rates: Higher rates in Scandinavian countries than in typically patriarchal Islamic nations, for example. So let’s see. Thanks to some data from the indefatigable Jeff Sonas, I was able to match up a country’s proportion of females among active, Fide-rated chess players against its gender equality score. The data below covers 1999-2015, but I also checked against a recent sample from November 2018 and the pattern is the same. Remember, for the stories above to be true, we’re expecting the the bars to get lower as we move from left to right. Here’s the actual result:

Surprisingly, it doesn’t look that way at all! In fact, if anything, the rates get higher as we move down the equality scale (we can show statistically that this is true). As expected, women are the minority in every country. But there’s still quite a lot of variation in rates. Denmark is the worst country in our list of participation, with only one female player to roughly 50 males, while the rest of Scandinavia as well as most of western Europe also languish at the bottom.

On the other hand, some of the best countries show evidence of the effect of female role models, and would be no surprise to players familiar with women’s chess history. Georgia (ranked 5th) and China (ranked 4th) both featured multiple women’s World Champions. There are also some high rates from a few unexpected sources: Vietnam (1st), the United Arab Emirates (2nd), Indonesia (8th), and even Kenya (12th) really buck the trend. Interestingly, a lot of the best countries for female chess players are in Asia. Besides Vietnam, there are five other countries in the best ten, and if I am a little more lenient with the chess population cut-offs, Mongolia and Tajikistan would also be in there.

Here are those 16 countries we mentioned earlier, but this time also ranked in order of female participation, and where I’ve highlighted the top and bottom halves by gender equality:

And here’s the complete sample of countries ranked in order of their female chess ratios:

So, the more gender-equal a country is, the fewer females want to play chess? What does it all mean?

There are a number of possible explanations, for which we can look to the broader research on gender. A recent, slightly controversial, school of thought fits with the chess results. Last year, a paper in Psychological Science discussed the so-called gender-equality paradox in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education. They found that while girls perform better than boys in STEM subjects at school, many more capable girls decide not to pursue STEM career than boys – and this gap is much larger in more gender-equal countries.

Then a few months later, a paper in Science, using data from 80,000 individuals in 76 countries, found that the more that women have equal opportunities, the more they differ from men in their preferences. The story goes along the lines that if women somehow biologically prefer NOT to compete with men, then they will be most able to show this in countries where women have more freedom to choose.

After 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6! leads to the so-called "Accelerated Dragon Defense". On this DVD the Russian grandmaster and top women player Nadezhda Kosintseva reveals the secrets of her favourite opening.

After 1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 g6! leads to the so-called "Accelerated Dragon Defense". On this DVD the Russian grandmaster and top women player Nadezhda Kosintseva reveals the secrets of her favourite opening.

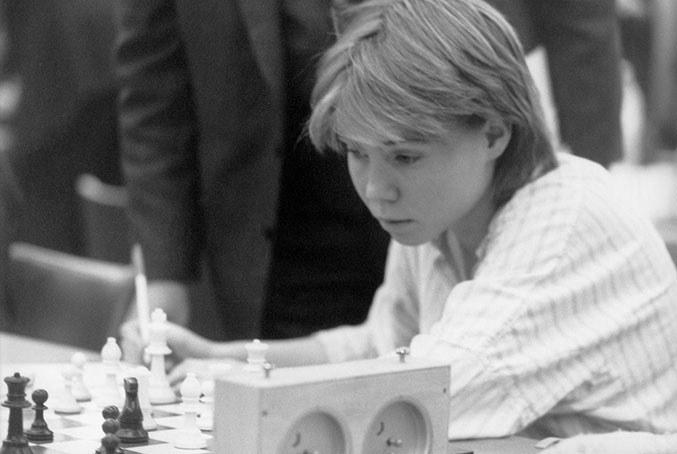

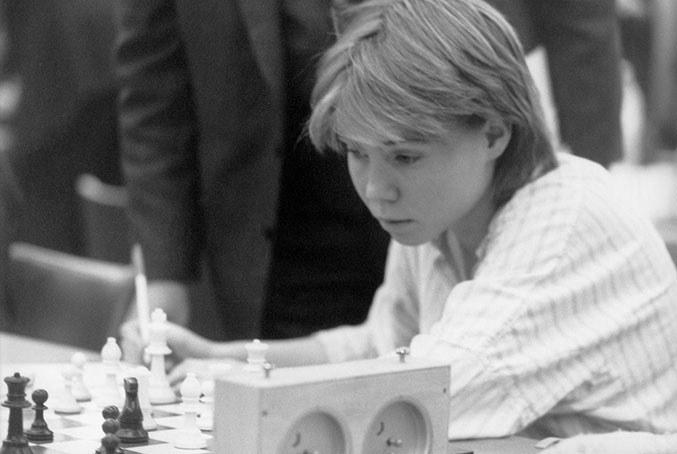

Pia Cramling did choose to play chess — despite Sweden scoring rather low in female participation | Photo: Bill Hook

Could it be that, deep down, women just don’t like chess as much as men?

Well, we can’t rule it out, but I doubt it. There are a lot of other parts to this story. For example, a different explanation is that women are more likely to play chess in gender-unequal countries because it’s one of the few fields where they can actually compete with men, and be sure that the result is judged without discrimination (as opposed to, say, promotions in the workplace). This story is plausible and I think worth investigating, though I haven’t worked out how to do it without more data.

Another alternative explanation that we CAN check is that our results are accidentally picking up the trend of worldwide increased female participation over recent decades. If countries with higher female participation are newer to international chess and therefore have younger chess communities, they will more likely reflect this trend. Here is a sample of the age distribution of male and female players across all countries:

We can immediately notice a few obvious features: there are more males than females at all ages, most people start playing when they’re young, and players of both genders start to drop out after primary school. There’s also an interesting point that many men come back to the game around their 40’s; this could be related to the period when a father’s kids become independent, but also might have to do with the surge in popularity due to the 1972 Fischer-Spassky world championship match. However, there’s no such resurgence among women, so the ‘Fischer effect’ seems unlikely.

Let’s check the graph for the countries with the lowest female participation rates:

The female graph looks predictably abysmal and the gender gap is massive even before the age of 10. The male graph also has a curious feature: the peak is actually around 50. There are a lot more older men in these countries.

But when we turn to the countries with the highest female participation rates…

…the picture is completely different. These are indeed ‘young’ chess countries. Strikingly, girls make up a sizeable share from a young age and maintain it until their early 20’s, after which the ratio drops sharply. This could be due to marital/childbearing pressures in these countries, but it could also be because chess organisations rarely focus on targeted female infrastructure after the junior years.

These results suggest that the age distribution of a country’s chess community plays a big role. The best countries for female players are those where there are a high share of girls playing from a young age. This could be because federations or school chess organisations make it a priority to focus on teaching chess to both genders. At the London Chess Classic last year, I asked the federation president of Mongolia (where females make up over a third of all rated players) the secret to their success. He told me that the federation has a clear goal to teach chess to every child, no matter what age, social background or gender. The focus on teaching girls when they’re young coincides with another strain of gender research, which argues that girls are ‘nurtured’ from a young age to believe they can’t (or shouldn’t) compete with boys.

Still, even among the top-ranked countries, there is the same exodus from the chess world of young adult women. Perhaps this is a neglected group in chess policies. There is often easily accessible infrastructure to play chess while in school, such as girls’ clubs and a higher frequency of female-only junior events. But after the age of twenty or so, it becomes decidedly more difficult for the average female club player to enjoy the game among other women. I don’t know what sort of policies might address this – promoting young women’s clubs, or perhaps introducing female quotas into more team events, as has been shown to be effective in recent research from French league data.

On the other hand, the effect of female chess role models is also an area to explore, while Asian countries seem to making the biggest headway towards encouraging women to play chess. Perhaps there’s a cultural element, or perhaps their chess federation policies are different – I don’t know, but it is definitely worth finding out. What’s clear from the data is that girls in all countries around the world are still leaving the chess world after school, and they’re unlikely to come back. We should encourage them to stay.

Links