.jpeg)

.jpeg)

Fritz and Chesster - Learn to Play Chess

Learn to think strategically, try out tricky mental exercises and master fun and exciting challenges – all with a generous helping of chess knowledge.

Unless you’re a competitive chess player, you probably hold a number of misconceptions about the game.

You might think chess players are smart people, or that learning to play chess well is correlated with intelligence. You might think chess is hard, or that you hopelessly suck, and it’s an impossibly tall task to consistently beat that one friend or relative who is the reigning champ. You might think chess is boring, that it’s an activity you’re not well suited for.

I used to think all of these things. I was wrong.

My dad taught me chess when I was five or six years old. He did it in the same boring way that most dads teach anything. First, he told me a bunch of stuff. We went through each piece and how it moves. He laboriously enumerated the rules of turn-taking and capturing and checkmate.

Next, we tried playing a game. This may have taken place many months later. I was probably too frustrated learning a million arbitrary piece movements to play a weird, annoyingly complicated board game with my father in the first sitting.

And of course, playing the game felt more like a chore than a reward. I would be absolutely clobbered on the board and frequently told I was explicitly wrong or implicitly stupid for missing obvious things. “Ah, did you consider this move son? Or what happens if you try this instead?” Many a dad just can’t help himself in pointing out corrections a bit more frequently than others are comfortable with.

On rare occasions, I would be momentarily fooled by my dad’s goofy playacting. If he let me win or inconspicuously guided me to capture a piece, I felt accomplished. I’d entertain brief hopes that there might be an easy road to better results. Maybe my feeble little brain could withstand the cold crushing complexity, the labyrinthine logic of chess. Such hopes would die as soon as I was reminded of our status roles as father and son, chess authority versus chess learner.

Finally, inevitably, I would leave the board feeling essentially humiliated. This feeling was often accompanied by a fit of childish rage, an “I hate you, I hate chess” monologue, and perhaps some pieces flying across the room. In hindsight, I could have skipped the chess entirely, reclaiming my precious youth instead by flinging things and smiling while gleefully shouting wingardium leviosa!

Despite whatever tricks and treats my dad attempted to leverage for the sake of the well-intentioned chess interaction, it always felt mildly painful. And this dynamic continued for years. I remained trapped in “chess learning for normal people” mode until I was twice my starting age. I guess there are far worse things out there, but still, it wasn’t the best—it was the hard way.

You’ve probably experienced this mode of learning in your life, whether it’s with a parent, teacher, student, friend, or romantic partner. The activity varies—cooking, painting, video games, cleaning, bird watching, golf—but the outcome rarely deviates. The teacher fails to inspire, and the student is left with a lingering sense of “I’d prefer if we didn’t do that.” It’s simply not fun; it’s an unpleasant situation to be avoided or escaped.

I found my way out in middle school, when a group of friends started to play chess in the cafeteria during indoor recess on rainy days. We competed as peers, exploring the game together. There was a lot more pure joy, a lot more dynamism and engaged interaction, when we played. And we stumbled upon a real treasure in the team chess variant known as bughouse.

In bughouse, you pass captured pieces to your partner for them to place at leisure on their board. The game is fast-paced, exotic, and exciting when compared with normal chess. There are wild, surprising swings when a piece lands in the middle of the opponent’s army, as if it were an alien beamed down from outer space. Add to that the competitive aspect of middle schoolers rotating in and out on teams, king-of-the-hill style, and you can quickly see how this game was more addictive than many multiplayer video games.

MVL and Carlsen play some bughouse against Caruana and Aronian

The fun of bughouse led to my joining the chess club in high school. With a newly cemented foundation of enthusiasm, I learned to study chess in earnest and play in serious competitions. Notably, it was only after a couple years of devoted study and play that I first began to appreciate the life skills and metaphors that chess is so publicly symbolic of.

The importance of planning for the future, of evaluating options and making tough decisions, staying calm under pressure, and working hard to improve oneself—all these things do not come in a rush to the student of chess. In fact, they probably come much sooner to people learning virtually any other sport or activity!

With basketball, you learn to handle the ball, pass it around, and refine your aim towards the hoop. The mechanics can take a while, but you understand the contours of the journey fairly immediately with your body. So you enroll in the journey and learn from it within that framework. You can see how sports relate to life, teamwork, discipline, planning, et cetera fairly immediately after a couple practice sessions with a coach or training partner. Because you’re not so hung up on the rules or environment.

Chess is different. You typically have to spend a ton of time learning the physics of chess first! It takes many weeks if not months for a dedicated student of the game to transition from “novice” to “beginner” level. In all my years playing chess with family as a kid, I never learned the core basic skills, let alone the full fancy rules of en passant or castling. I would say I, like many others (and perhaps you) stayed a chess-exposed novice for a very long time without any significant progress or joy.

Reflecting on this journey, I now see how it could have been accelerated. I could have bypassed the initial years by jumping straight into the middle school peer experience of fun chess and bughouse. Then I could have moved more quickly to the high school challenge of getting intimate with the game.

We’ll have to save the full story of my chess career for another time, but I will mention one more interesting milestone—when I became the father figure in high school, trying and failing to teach chess to my little sister! It was hard to convey why chess was interesting at all, and I now deeply regret crushing her without mercy through the years. I wish I had known then what I know now…

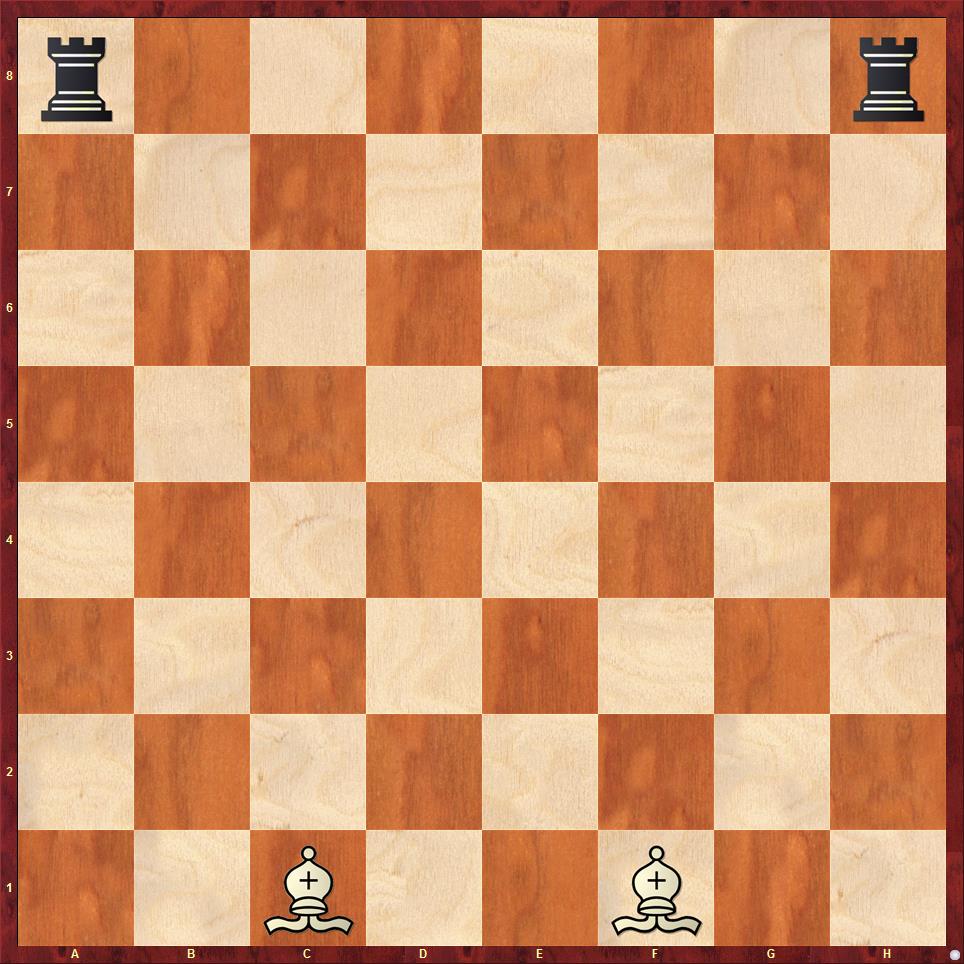

So let’s dive in (to this one weird secret trick that doctors hate): learning chess can be done quickly and transformatively through minigames! The starting place is Bishops + Rooks.

This is a minigame in which white moves a bishop first, then black moves a rook, and whoever captures a piece first wins. It’s a draw with best play, but getting to that skill level may take a second grader a month of lessons. During this time, she will get a ton of instructive value from playing the minigame again and again.

I could say a lot more about Bishops + Rooks and how to best utilize this teaching tool. Feel free to check out my written guide here and explainer videos here! There’s a whole suite of such content, including follow-on minigames like knight battleship, pawn wars, zombie chess, and more. For the purposes of this essay, I’ll give one additional example here then wrap up with some concluding takeaways.

This minigame teaches King Opposition, and it’s a good starting place for adults who are quick to master Bishops + Rooks. I don’t recommend it for younger kids until they are enthusiastic tournament players, since the exercise can feel too abstract and tedious.

As with Bishops + Rooks, standard piece movement rules apply, but the objective isn’t checkmate. Instead, white tries to get the king to a8, b8, or c8 while black’s goal is to block this from happening with her king. There’s a forced win for white that makes beautiful use of the real-game principle called “distant opposition” which I won’t explain here but encourage you to explore…you can find plenty of practice online.

I’ve found playing this minigame with interested or even tentative friends to be extremely rewarding. Following up with king and pawn vs king scenarios then queen / rook checkmates usually leads to an enlightening “aha” experience. The most common reaction is, “I’ve never seen chess like this before.”

Starting with a couple pieces instead of a complete set is crucial to teaching and learning chess the easy way. With these minigames, novices have a well-defined environment in which they quickly come to grapple with the fundamental skill of chess: finding options, thinking through them rigorously, and deciding on reasonable ones—in a word, strategy.

The “easy way” isn’t meant to imply that learning chess or strategic thinking is easy. Rather, minigames are more understandable bite-sized chunks to chew on and engage with, when compared with traditional rote verbal methods that try and fail to teach everything at once.

Another benefit is the level playing field minigames create. An advanced friend and her beginner friend can engage in a realm where both sides stand a chance at winning, or at least not losing horribly and ambiguously. The person with less chess experience feels comfortable making mistakes because it’s more obvious how they themselves can detect and learn from them. That’s empowering.

Lectures never have this tangible, experiential quality, which is why I believe it’s best to dive into silently playing minigames as soon as possible. The more rules there are to explain and memorize up-front, the more likely it is that folks end up in the sorry state of “chess learning for normal people”. Don’t make people learn chess the hard way!

If you’re in the teacher’s seat, with anybody but especially with young children, please bear in mind that they may be unfamiliar with the process of navigating on their own. Chess can be one of the first experiences in a person’s life when they really get to see the complete physics of a contained situation and to operate fully autonomously within such an environment.

Be extra patient, watch silently, and let them explore on their own as much as possible. Allow the outcome of the game to teach them their mistakes. You don’t need to point out the correct answers. Give them a fun time and the opportunity to play again. Debrief with questions like “what did you learn from playing today or notice that was interesting to you?” It’s really wonderful how many doors open with this kind of self-propelled learning journey and accompanying self-confidence gains.

The truth is that chess can and should be stimulating and fun and empowering, from the beginning. It’s inherently interactive, and although it’s a zero-sum competition over the board, it’s more importantly a series of tractable challenges which provide a medium for self-improvement and social engagement.

In the era of COVID-19, humankind is riding the swelling wave of screens and isolation. Now more than ever, it’s especially important to have these kinds of healthy media of exchange and growth with our friends, families, and children.

Find a partner and try out a minigame! Everyone can experience and appreciate what it means when I (and others) think of chess fondly. It’s all about having the right tools and mindset to get started on a rainy day in a fun, approachable way.

This article first appeared at https://andytrattner.com/chess-the-easy-way.html. Republished with kind permission.