Perfect endgame analysis and a huge increase in engine performance: Get it with the new Endgame Turbo 4! Thanks to a new format (Syzygy-Tablebases) the Endgame Turbo 4 is smaller, faster and yet has more scope than the old version.

It was some time in the early 1980s. Ken Thompson, the man behind Unix and the computer language C, had built a hardware chess machine named Belle, which duly won the World Computer Chess Championship. Ken had also resolved a dispute with IM David Levy on the feasibility of generating endgame databases — by actually generating a four-piece database, king and queen vs king and rook. Soon after it was completed, we had a lot of fun, at a tournament in New Jersey, challenging top players to win with the queen. "But that is quite easy," they would say, only to fail again and again against the optimum defence of the computer. One prominent victim: GM Walter Browne, three times US Champion.

After one of the rounds in New Jersey we sat in Ken’s car waiting for someone who would be getting a ride. It took far longer than expected, and I used the opportunity to elicit more information on how his "endgame databases" were constructed. Ken explained: you generate every legal position with the given material — for KQ-KR there are 1.9 million of them — and store them on a hard disk. Then a program examines each position to see if one side is mated. If that is the case the position is marked with a zero. Now it retracts one legal move from all positions that are marked zero and marks them with a one. These are positions that allow one side to deliver mate in one move.

Now the program takes all positions marked with a one and retracts all legal moves from each of them. It checks these positions for ones in which every legal move leads to a position that was previously marked. Such positions are marked with a two. They are positions in which the side to move will be mated by force in two ply (half-moves).

In the above schematic, taken from the German language book Steinwender/Friedel, Schach am PC, Markt&Technik 1995, positions with White to move are depicted as circles, Black to move as squares. In the first diagram positions in which Black is mated are marked zero; in the second all positions in which White can mate in one move are marked with a one; and in the third diagram all positions with Black to move that lead only to positions marked one are marked two.

The process is continued until all 1.9 million positions have been processed. With the hardware available at the time (a mainframe in Bell Labs, New Jersey) it took half a day to process the endgame. The result: over 1.7 million positions got a number between 0 and 61, which means that the maximum length of a win in the endgame queen vs rook is 31 moves. Since more than 90% of all positions are marked, this endgame is considered a win for the side with the queen. It is interesting to note that there are exactly two positions that require the maximum number of moves. One of them is wKa8, Qa5, bKf6, Re8, the position that Walter Browne could not win in 50 moves.

But what about the 10% of unmarked positions? Many are "pathological positions" in which Black can exchange the rook for the queen, e.g. wKb1, Qa1, bKb8, Rh1, which is an immediate draw (1.Kb2/Ka2 Rxa1). In fact Black wins if the white king is on d1, e1 or f1. But there are also more complex draws. The following has been known for over two hundred years:

The rook keeps checking White from h7, g7 and f7. If the white king moves onto the e-file then …Re7 pins the queen and wins it; and if the king moves to f6 or h6 then …Rg6+/Rh7+ forces stalemate.

Before we proceed with the narrative, there are two little stories I need to insert. They have been told before, but many readers may not be familiar with them. The first is that, at a tournament in Brussels, I got Karpov and Kasparov to sit together in front of my Atari ST and try to win queen vs rook. It was a hurried attempt in the press room after a round. They did not succeed, and laughed in amazement over the computer’s defence.

The other is about a 14-year-old chess talent who stayed at my house and whom I asked if he could win with the queen vs the rook. "Of course I can," he said, only to fail against the computer.

The next morning at breakfast he announced he had found the strategy to win, and proved it with flawless play against the computer. The lad, whose name was Peter Leko, had actually worked it out in his head, while lying in bed in the dark. – Photo Peter Leko in 1992 | GFHund CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Back to the parking lot in New Jersey. I was very excited by the way the computer had stood up to GMs and IMs in the four-piece endgame, and eager to understand what endgame databases meant for the game. “When computers have calculated the 32-piece ending they will play 1.e4 and announce mate?” I asked. “No!” answered Ken emphatically, and proceeded to explain in a parable. I wrote this up a couple of years later, for a German chess magazine, and drew a fair bit of consternation and ire over it. At the time Garry Kasparov had ascended to the top of the chess world, and I inserted him into Ken’s narrative. Anyway, here goes…

One day World Champion Garry Kasparov, who towers above all his rivals, reached an Elo of 3000. When the rating list was released the heavens over Baku opened and an Angel of the Lord descended. He approached Garry and said: “For what you have achieved you are invited to play a game of chess against God.”

Garry was overwhelmed. He dressed into his finest and got onto the golden escalator that transported him to heaven. There the Angel led him into a small room where God was sitting, drinking coffee and looking at a computer screen. Garry was somewhat surprised that He was wearing jeans and a t-shirt, and had a fairly unkempt white beard. He bowed deeply and said:

“Oh Almighty Lord, Creator of the Universe…”

“Just call me God,” God interrupted. “Or G, which is what most of my friends call me.”

“Okay, God, it is a great privilege for me to stand in your presence and to actually play a game of chess against you. Of course I have absolutely no expectation of winning. I assume you play a perfect game!?”

“Yes,” replied God, “I have done the 32-piece endgame.”

“Ahh,” said Garry, “Of course that is trivially easy for you.”

“No, no,” said God, “it was really tough. More than 10^35 legal positions — it took the matter from a good-sized planet to store. But let us play. You can have white.”

So Garry played his favourite 1.e4, expecting an exciting Sicilian. But after a few moves the game had left all known theory and a weird position was on the board. Actually God’s position was in shambles. "This is divine humour," Garry said, "You want me to have a chance, God?" But He just smiled and said "No." Soon Garry was two pawns up and had an overwhelming position. "But I am winning for sure now," he said. "No," said God, "it is a draw. The whole game is a draw. Can’t be won."

Garry was not convinced. He played on with great attacking moves, and even won an additional piece. Surely now he was completely winning. He reached a stage where it was clearly only a matter of technique to mate the opponent. However, try as he might, he was not able to actually deliver mate. There was always some unexpected defence, some bizarre move that prevented it. He tried this and that, but somehow could not succeed.

Then suddenly God interrupted a phone call he was making and stared in disbelief at the board. "My Self!" he said, "It’s a win! I haven’t seen one in a billion years." "But I can’t find it," said Garry, "I cannot seem to convert my advantage to a mate." "Oh, no," God said, "it is a win for me — for Black. This only happens once in a decillion times."

The game proceeded, and God, now fully concentrated, started making moves that were completely incomprehensible to Garry. But they slowly improved Black’s position. Soon the game was equal, and then Black started to take what for Garry seemed to be the "initiative". Then, in a flurry of unexpectedly brilliant moves, he found himself mated.

"I will be eternally grateful, God, for this demonstration of your omniscience," Garry said in parting. "I thank you for a very interesting game, Garry," God replied. "A one in a billion experience."

So what was Ken telling me in that carpark? First of all that calculating the 32-piece ending, i.e. comprehensively solving the game of chess, was beyond the scope of the current universe. "Just storing the data requires you to dismantle an entire planetary system," he said. "Just imagine what Greenpeace would say to that!"

Secondly Ken was predicting that the game of chess was a draw, i.e. that probably a majority of all legal positions, including the starting position, would lead to a draw with perfect play. Both sides can always play moves that lead to unmarked (drawing) positions. He also drew my attention to a problem he had with his four and later five-piece endings: if the computer had a position that was a draw it would not try to win. It sometimes sacrificed its superior material because that did not change the outcome of the game. In the Ponziani position given above his computer would be willing to exchange the queen for the rook at any stage, because it did not affect the final result.

In the meantime all five, six and seven-piece endings have been calculated, and stored in databases of five hundred trillion positions. Of course the play of these endgame programs is completely incomprehensible, but Ken’s prediction that the game itself, in the 32-piece version, is probably a draw, seems plausible. And this is further confirmed by the recent experiment with AlphaZero. The system achieved super-human chess skill after just four hours of "thought", probably achieving something in the range of a 3700 rating. So the question arises: what happens if you let the system ponder for eight hours, or for eighty, or run on a far larger number of processors? My prediction: it will not cross Elo 4000 — nothing ever will. The draw in chess will prevent that from happening: a 3900 program will always be able to hold the game, however strong the opponent.

But this is a discussion for a future article, which will include the opinions of leading experts and hopefully some of those from our more thoughtful readers.

The multiple computer chess world champion comes in a new and yet more powerful version. Thanks to co-author US Grandmaster Larry Kaufman, Komodo is the strategist among the top chess programs!

In the years after the pioneering work with four-piece endings, Ken Thompson and others worked out all five-piece endgames, which have between 212 and 335 million positions each. And then came the six-piece endings, which required truly massive computing power to calculate — and plenty of hard disk space to store. Russian programmer Eugene Nalimov created a new format that required eight times less space than the previous versions. And in 2013, Ronald de Man developed the "Syzygy Bases" that were in turn seven times smaller than the Nalimov tablebases. For the first time it was possible (or practical) to provide users six-men tablebases on DVDs.

In the years after the pioneering work with four-piece endings, Ken Thompson and others worked out all five-piece endgames, which have between 212 and 335 million positions each. And then came the six-piece endings, which required truly massive computing power to calculate — and plenty of hard disk space to store. Russian programmer Eugene Nalimov created a new format that required eight times less space than the previous versions. And in 2013, Ronald de Man developed the "Syzygy Bases" that were in turn seven times smaller than the Nalimov tablebases. For the first time it was possible (or practical) to provide users six-men tablebases on DVDs.

If you buy one of our chess programs, they will already play a number of four and five-piece endings (e.g. Q vs R or R+P vs R) perfectly. With Endgame Turbo the programs will play all important five and six-piece endings perfectly. They will in fact use the endgame knowledge in the search, so that positions with many more than six pieces that can be traded down to advantageous six or five-piece endings will be handled perfectly as well.

Houdini 6 continues where its predecessor left off, and adds solid 60 Elo points to this formidable engine, once again making Houdini the strongest chess program currently available on the market.

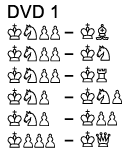

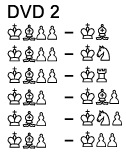

Endgame Turbo 4 contains all five and 27 of the most important six-piece endgames in the Syzygy format, which can be used with top engines like Komodo or Houdini. Endgame Turbo 4 consists of four DVDs with the following endgames:

|

|

|

|

You can order Endgame Turbo 4 in the ChessBase shop here.

Price: €59.90 – €50.34 without VAT (for customers outside the EU) and $54.03 (without VAT).

Expect to read more about five and six-piece endgame databases in a future report.