Chess Explorations (52)

By Edward Winter

From page 678 of the October 1975 Chess Life & Review:

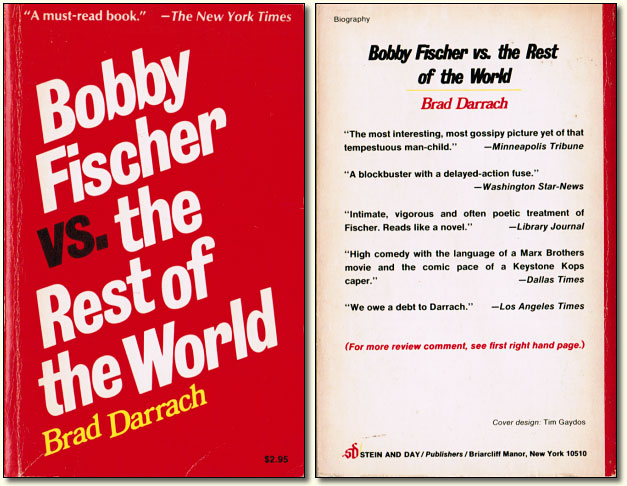

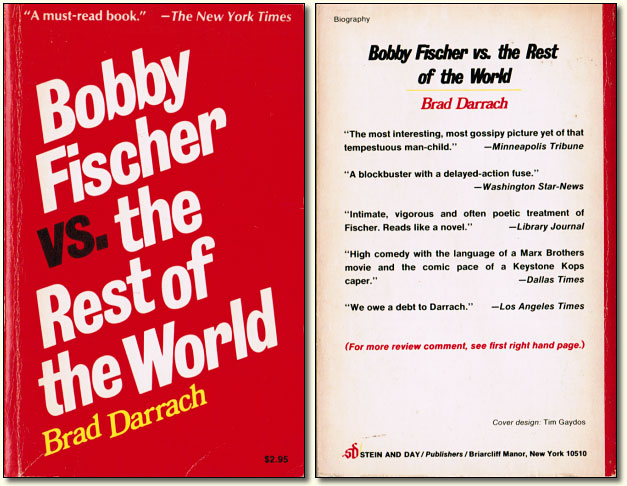

‘A UPI item in the New York Sunday News, datelined Los Angeles, 30 August, reports Bobby Fischer is suing Brad Darrach, Time-Life International and Stein and Day (publisher of Darrach’s Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World) for $20 million.’

Earlier in the year, an advertisement had appeared in the same magazine, on page 19 of the January 1975 issue:

Chess Life & Review returned to the subject on pages 299-300 of the May 1975 edition, when its Editor, Burt Hochberg, discussed an article (‘by somebody named D. Keith Mano’) about Darrach’s book which had appeared in the New York Times Book Review, 13 October 1974. Mano had concluded that ‘men who play at the grandmaster level are, almost without exception, strange and unpleasant’, which prompted Hochberg to comment that Mano had been misled. Darrach’s book, Hochberg added, ‘is unbalanced and unfair; he has taken an extremely complicated and tortured genius and subjected him to an almost morbid scrutiny at the most critical and stressful period in his life’.

Hochberg (a fine writer and editor, unjustifiably disregarded nowadays) added:

‘Mr Mano has fallen into a trap; he sees Fischer the nut, Fischer the unreasonable child, Fischer the pathologically repulsive – all through Darrach’s eyes, for of course Mr Mano does not know Fischer. But Darrach does not really know Fischer either; no-one can really know him who does not understand chess. Strange Fischer may be, even to his friends in the chess world, and unpleasant he is at times – but who isn’t? In Fischer’s case, his unpleasantness is obvious to journalists because they know nothing about chess and are incapable of correctly interpreting anything Fischer says or does.’

The rebuttal by Hochberg concluded:

‘... Fischer is not perfect. He is not even close. But he deserves to be treated fairly and with some attempt at understanding. If he were not the man he is, he would not be the greatest chessplayer the world has ever known.’

Darrach’s reply in the newspaper (23 February 1975), which included the claim that ‘The book shows Fischer as superhuman, subhuman and normally human (whatever that is) in different proportions at different times’, was also discussed by Hochberg. He observed that Darrach ‘will not hesitate to sacrifice accuracy for the sake of a good line’ and concluded that the book mainly comprised ‘incidents chosen to show Fischer in the worst possible light’. It was ‘a hatchet job’.

On the next page of Chess Life & Review a reader requested Larry Evans’ view on whether the Darrach book was fair and accurate. The reply included the following opinions:

‘Darrach is not always fair and not always accurate, but his book is clever and gives a better picture of what Bobby is really like than anything else ever written. In my review for newspapers I noted that: “Darrach’s anecdotes are choice and indiscreet. Little escapes his keen eye, and he was the only reporter allowed to shadow Bobby after promising not to write a book about him.”’

Evans’ ‘review’ can be found on page 9 of his book The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982). From the first paragraph:

‘This hilarious portrait of a genuine loner reads like a novel as it recreates the inglorious saga of the title match in Iceland. Bobby is revealed as an idiot-savant who can neither cope with nor fathom the forces driving him. A moody genius.’

(See also, in this connection, C.N. 323, reproduced on pages 208-209 of Chess Explorations.)

In contrast, Fischer’s biographer, Frank Brady, wrote on page 808 of the December 1975 Chess Life & Review:

‘... Fischer is no idiot savant, no Grandmaster Cro Magnon, as he is constantly portrayed in the popular press and in worthless hatchet jobs like Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach.’

The French term cropped up yet again in Yasser Seirawan’s discussion of Fischer on page 293 of the book he co-wrote with George Stefanovic on the 1992 Fischer v Spassky match, No Regrets (Seattle, 1992):

‘The media had a field day. They could write anything they wanted, both real and imagined.

The coup de grâce was Brad Darrach’s book, Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World, that forever nailed Bobby as the horrible combination of idiot savant and enfant terrible. This single work undoubtedly influenced multitudinous journalists to write about Bobby in exactly the same way. This book would prove to be a monkey on Bobby’s back. He would find himself forced to fight back against the media.’

The Darrach book has certainly been influential. For example, Bobby Fischer Goes to War by David Edmonds and John Eidinow (London, 2004) made liberal use of it and even had, on page 153, two sentences which started with the same demeaning phrase: ‘According to Darrach’.

Fischer v Spassky in Reykjavik (front-cover photograph of How Fischer Won by C.J.S. Purdy (Sydney, 1972))

This Crazy World of Chess by Larry Evans (New York, 2007) began with an item entitled ‘Fischer Letter to Marcos’ which Evans had originally presented in 2004. The letter was dated 27 January 1975 and began ‘Dear Mr President, How are you?’. It included this passage:

‘... I’ll be starting a suit of my own against someone who has written an incredibly boring book about me [Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World by Brad Darrach] that’s being pushed as “the most deliciously indiscreet biography ever written”. I think it should be called the most inaccurate biography ever written! But we can’t expect much accuracy from the press.’

That last sentence, at least, is hardly open to dispute, and mainstream journalists have seldom paused to wonder how much of Darrach’s narrative and dialogue was true. The text is too colourful for any qualms about using it freely and with relish. In 1975 Stein and Day brought out a paperback edition, which quoted commendatory phrases such as the following from the Dallas Times:

‘High comedy with the language of a Marx Brothers movie and the comic pace of a Keystone Kops caper.’

But what about the issue of truth, the question of Fischer’s right to privacy and the wealth of direct speech? Discussing Chess Scandals: The 1978 World Chess Championship by E.B. Edmondson and M. Tal (Oxford, 1981) we commented in C.N. 509:

‘The late Colonel provides a mass of documentation tracing all the unbecoming disputes that marked the 1978 match as one of the most bitter in the game’s history. It seems strange that the 1972 Fischer-Spassky match did not give rise to such a book (we are discounting the scurrilous fiction of Brad Darrach).’

On 13 September 1983 Anthony Saidy (Santa Monica, CA, USA), who was frequently mentioned in Darrach’s book, wrote to us:

‘How accurate you were to describe Darrach’s “scurrilous fiction”! He writes superior pulp novel stuff.’

The views quoted so far have come from the compatriots of Fischer and Darrach, but the reception accorded to Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World across the Atlantic was also highly diverse. In fact, the British Chess Magazine, edited by Brian Reilly, gave the book no reception of any kind, whereas the brasher CHESS (editor: B.H. Wood) had a field day. A cover page of the May/June 1975 issue mentioned that the book was in limited supply and gave readers every encouragement to place an early order:

‘Racy dialogue and a breathless hard-hitting style ... gripping stuff.

To what extent spontaneous conversation can be accurately reproduced years later is, of course, debatable.

The book is full of it, revealing R.J. Fischer as an obnoxious person indeed. As Brad Darrach has contributed to Life, Esquire, Harper’s and other magazines and (on the lines of this book) to the English Daily Telegraph supplement and attended the 1972 match at Reykjavik in person, we might assume that he has tackled his reportage responsibly. In the eyes of an ordinary man not blinded by hero-worship, Fischer emerges as a pretty noxious individual.’

Thus Fischer was described within a single paragraph as both obnoxious and noxious. Concerning Darrach, the grounds on which ‘we might assume that he has tackled his reportage responsibly’ scarcely appear rock-solid, but B.H. Wood was never an enemy of gossip.

The paperback edition of Darrach’s book received a mention among the cover pages of the February 1978 issue of CHESS, which showed that the magazine’s enthusiasm for such reportage had not diminished:

‘Deliciously sordid, and controversial, account of the clash of ’72. Racy, amusing prose and vivid portraits of even the minor characters give the book the air of a “non-fiction novel”.’

By that time, the lawsuit had come and gone. On page 238 of the May-June 1975 CHESS Frank Brady wrote:

‘... Fischer had other business matters to be discussed, including the possibilities of instigating a legal suit against author Brad Darrach for his book, Bobby Fischer vs. the Rest of the World, most of which, Fischer claims, is libellous and untrue (as do many others in the chess world, including myself; Saidy calls it a “great work of fiction”) and also violates an agreement that Fischer had with Darrach that the latter would not write a book while covering the Fischer-Spassky match for Life magazine.’

Pages 80-81 of Playboy, July 1973

As mentioned earlier, Fischer sued Darrach for $20,000,000 in August 1975. The outcome of the case, two years later, was related by Frank Brady in a detailed article (‘Bobby Fischer Pilloried – His lawsuit collapses because he disdained legal aid’) on pages 364-365 of the September 1977 CHESS. Brady’s main points are quoted below:

-

‘... to solidify his reputation as a loner, Fischer prepared the legal brief himself, without the aid of an attorney.’

-

‘After two years of postponements on the part of the defendants, the case recently came before US District Court in the state of California and was dismissed by Judge Matt Byrne on the grounds that Fischer’s brief was not properly prepared.’

-

‘As Fischer’s biographer, I must admit that he is difficult, intense, and often detached but he is certainly not the uneducated and hysterical pet-baboon that Darrach so vividly but so inaccurately develops.’

-

‘Darrach signed two documents, now in Fischer’s possession, stating that he would not write a book about Fischer. He also made numerous oral promises to that effect. I have before me copies of Darrach’s letters to Fischer.’

-

‘Using the ploy of postponements, hoping that Fischer would relent from lack of money to continue the case, was Darrach’s and his attorney’s only hope. As it developed, a technicality has temporarily saved them but Fischer will undoubtedly win the appeal ... if he allows himself to secure proper legal aid.’

-

‘Actually, without Bobby’s or anyone else’s knowledge Darrach had made the rounds of New York publishers prior to going to Iceland, attempting to secure a contract for a book. In Iceland, he snooped and wormed his way around attempting to find out as many intimate details in Bobby’s skeleton closet as he could. This was material that Life had no interest in publishing. Even Stein and Day, the publisher, deleted much gossip about Fischer’s private life before the book went to press.’

-

‘A large part of the book covers Fischer’s peregrinations before deciding to go to Iceland. Darrach weaves a colourful account of those moments and quotes long sections of dialogue, as though he were on the scene and heard the specific conversation. In fact, Darrach was already in Iceland, Fischer was in New York and most of the material that Darrach relates as history is just an exercise of his imagination.’

-

‘Other persons mentioned in the book are having trouble with Darrach. Two other chessplayers – one an international grandmaster – seriously considered libel suits against him. One of Fischer’s oldest and closest friends, hardly a public figure, is described in a particularly vicious and harmful way. He is currently preparing a lawsuit. Dr Max Euwe and Lothar Schmid are furious over Darrach’s unfair treatment of them.’

-

‘Certainly, these legal difficulties are a crucial factor in keeping Fischer from the board.’

We have yet to find details regarding an appeal by Fischer or any other lawsuits against Darrach.

In CHESS B.H. Wood conspicuously distanced himself from Brady’s analysis and gave the article this heading:

‘Frank Brady, official biographer of Fischer, whose opinions as an unreserved supporter of the ex-world champion are very definitely all his own.’

At the end of the Brady article CHESS opined:

‘Darrach is sometimes grudgingly fair to Fischer but obviously loathes him. He stresses the mad genius’s merciless eccentricities. He has researched assiduously though nobody could have attended every personal encounter written up in such vivid dialogue. The facts are all basically authentic, as to prompt the question again and again “Could anyone behave like this?”

A gripping book, almost a work of genius whose bad faith, which Frank Brady documents so fiercely, is another matter.’

It is unclear how CHESS felt competent to affirm that ‘the facts are all basically authentic’.

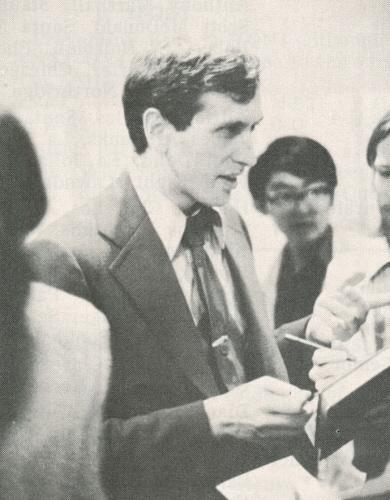

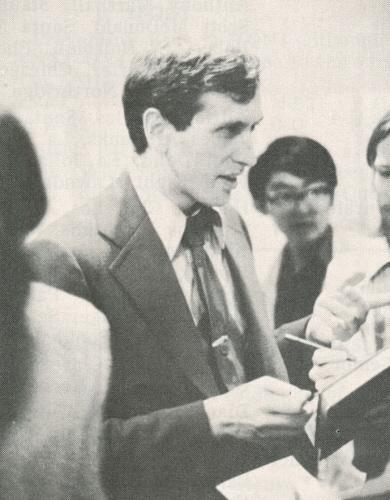

Bobby Fischer (Chess Life & Review, February 1973, page 71)

Independently of who was closest to the truth about Fischer in the 1970s, the subsequent revelations as to his character naturally cannot be ignored. In a 2005 Afterword to a feature article we observed:

‘From the late 1990s onwards he gave a series of radio interviews in which, egged on by standardless “broadcasters”, he came out with the most abject set of utterances ever made by a chess master.’

Yet there was even worse to come. The extent of Fischer’s depravity, anti-Semitism and, it must be said, apparent insanity was shown when a selection of his personal notes and other memorabilia was reproduced in Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David and Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2009).

Fischer articles by Edward Winter:

Submit information or suggestions on chess explorations

All ChessBase articles by Edward Winter

Edward Winter is the editor of Chess Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then, over 6,840 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by Winter: Chess Explorations (1996), Kings, Commoners and Knaves (1999), A Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph on Capablanca (1989).

Edward Winter is the editor of Chess Notes, which was founded in January 1982 as "a forum for aficionados to discuss all matters relating to the Royal Pastime". Since then, over 6,840 items have been published, and the series has resulted in four books by Winter: Chess Explorations (1996), Kings, Commoners and Knaves (1999), A Chess Omnibus (2003) and Chess Facts and Fables (2006). He is also the author of a monograph on Capablanca (1989).

Chess Notes is well known for its historical research, and anyone browsing in its archives will find a wealth of unknown games, accounts of historical mysteries, quotes and quips, and other material of every kind imaginable. Correspondents from around the world contribute items, and they include not only "ordinary readers" but also some eminent historians – and, indeed, some eminent masters. Chess Notes is located at the Chess History Center. Signed copies of Edward Winter's publications are currently available.

Edward Winter is the editor of

Edward Winter is the editor of