Last week we showed you a chess position presented by the famous mathematician Sir Roger Penrose – probably composed by his brother, GM Jonathan Penrose. It was devised "to defeat an artificially intelligent (AI) computer but be solvable for humans."

The position, which Penrose writes "scientists have constructed in a way to confound a chess computer," looks like a clear win for Black. However an average chess-playing human can see that a draw is possible: Black has no legal moves except with his bishops, so all White needs to do is simply move his king around and let Black make pointless bishop moves. There is absolutely nothing Black can do to force a win.

A chess program will not "see" the draw but display in its evaluation a very big advantage – 25 to 31 pawns – for Black. "The three bishops force the computer to perform a massive search of possible positions that will rapidly expand to something that exceeds all the computational power on planet earth," the Penrose Institute wrote, making a big deal out of this. But the position and the logic behind the experiment is not compelling: any chess program, playing the white side, will hold the draw flawlessly, even if it displays high negative values for White.

When writing the article I was reminded of a similar stuation that had occurred almost four decades ago:

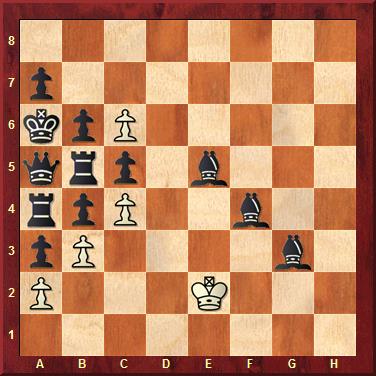

David Levy - CHESS 4.8, Hamburg, 7.2.1979

The Scottish champion IM David Levy was playing against the most powerful computer in the world, and after 73 moves had reached the above position (the entire game is described below). CHESS 4.8 displayed an evaluation of plus nine pawns for White, but it defended the game perfectly, and Levy was unable to win.

The position is a theoretical draw, as chess engines today will instantly recognize – because the endgame queen vs c or f-pawn is apparently part of their chess knowledge. For CHESS 4.8 this was not the case, but the program was able to survive by doing a pure brute force search and simply not letting White capture the pawn. The defence, as given in the annotated game below, is to only allow the pawn capture on c2 when the black king is on a1, so that it would be a stalemate.

The situation is similar to the Penrose example. Here any human player who has been following centuries of chess research can immediately recognize that the above postion is a draw, but the computer did not and evaluated it as a dead loss. But: it played the position perfectly and defended it to the draw it did not "see".

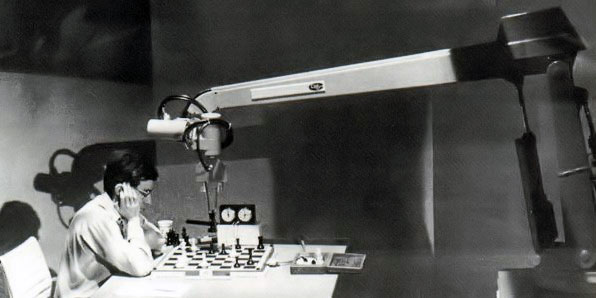

I want to use the above position for a trip down memory lane. As a rookie science journalist I was working for the German TV station ZDF in 1979, having a lot of fun doing so. One day I read that computers were playing chess, and in fact one of them had beaten a grandmaster in a blitz game. I took the idea of doing a documentary on the subject to my boss, the eminent science journalist Hoimar von Ditfurt, who immediately commissioned a film.

At the time IM David Levy, who was Scottisch Champion in 1968, had just won a well publicized bet against a number of famous artificial intelligence researchers (John McCarthy and Donald Michie amongst them). They had predicted, in 1968, that in ten years a computer would beat the world chess champion. Levy bet them £1,250 that no computer would win a chess match against him in those ten years. In 1978 he had survived all attempts. As part of our documentary we decided to invite Levy to Hamburg to play an exhibition game against a computer, the strongest in the world at the time.

The was program CHESS 4.8, running on a CDC Cyber 176 located in Minneapolis, programmed by two pioneers of computer chess: Larry Atkins and David Slate, computer scientists at Northwestern University

Producing the ZDF computer chess documentary was quite exciting – I got to go to Northwestern (Chicago) to interview Slate and Atkins, and to Moscow to talk with Mikhail Botvinnik, who was also experimenting in chess programming.

In our studio in Hamburg we hooked up the Cyber 176 to a sensor board and an industrial robot arm. Using a satellite line the computer actually sensed the moves made by Levy and used the robot arm to execute its own moves. German GM Helmut Pfleger commented for the studio public and the TV audience.

The program was a great success (and dragged me into the chess world). Europe's largest news magazine, Der Spiegel, reported extensively on the game and our documentary, and in fact staged a second match between CHESS 4.8 and Viktor Korchnoi a short while later (Korchnoi won comfortably).

In our ZDF program we offered to send the game notation, annotated by David Levy, Helmut Pfleger and the computer itself, to viewers who wrote in. A week later I was called to the studio, where a somewhat distraught manager led me into a room which had a number of sacks of mail: a total of 95,000 viewers had requested our notation! I produced a three-page printout and we hired a bunch of students to send out copies in this record-breaking action.

I still have the printout, but it is all in German. So I translated it into English – back into English in the case of Levy's notes – and have prepared a replay board for our readers. It is meant as a document to show the state of computer chess in the very early days. Remember that the Cyber 176 was probably as powerful as the hardware in your TV set or microwave oven, and that many of the algorithms that have pushed chess engines today to 3300+ Elo strength had yet to be discovered. Still, it is an interesting game and of historical interest.

[Event "ZDF"] [Site "Hamburg"] [Date "1979.02.07"] [Round "1"] [White "Levy, David"] [Black "Chess 4.8"] [Result "1/2-1/2"] [ECO "C37"] [Annotator "Levy/Pfleger/Chess"] [PlyCount "178"] [EventDate "1979.??.??"] 1. e4 e5 2. f4 {Pfleger: The small David dares to play the wildly romantic King's Gambit against the tactical Golaith computer.} exf4 3. Nf3 g5 4. d4 { Levy: 4.h4 or 4.Le4 are normal, but I was afraid that the machine would know much more about this variation than I did.} g4 5. Bxf4 gxf3 {[#]Levy: This variation has never been played in master level chess. It is the invention of the Estonian GM Paul Keres. Pfleger: Both players are now in unknown waters and cannot rely on things they have learned by heart.} 6. Qxf3 Nc6 {Here CHESS for the first time thinks for more than a millisecond. The computer takes 245 seconds to check 713,868 positions before making its move. It considers the position positive for Black, to the tune of 1.26 pawns.} 7. d5 Qf6 ({CHESS expected} 7... Nd4 8. Qf2 Bc5 9. Nc3 {when it played 6...Nc6, but after Levy actually played 7.d5 CHESS had calculated deeper and did not go for 7...Sd4.}) 8. dxc6 Qxb2 9. Bc4 {Pfleger: Too daring. White should have played Qb3, although here too one can expect treacherous complications. It is doubtful if the mating attack, which White probably planned, can be executed. Levy: Premature and without sufficient thought.} ({Instead I should have played} 9. Qb3 Qxa1 10. cxb7 ({or} 10. c3 -- 11. Bc4 -- 12. O-O)) 9... Qxa1 10. Bxf7+ Kd8 ({Pfleger: After swallowing the fat rook the electronic brain does not fall for the trap} 10... Kxf7 11. Be5+ {[%cal Re5a1,Rf3f7,Gf4e5] winning the queen.} ) 11. O-O Qg7 {[#]Levy: Well played by the machine! At this point I realized that my rook sacrifice probably would not pay off. CHESS played this move to Levy's consternation without any thought.But checking the log files revealed that it had looked at just under four million positions. The explanation: CHESS made use of the opponent's thinking time, and Levy had used almost 20 minutes pondering his previous move. When he made it the computer had its reply ready.} 12. Bd5 Bc5+ 13. Be3 Bxe3+ 14. Qxe3 dxc6 15. Rf7 Qh6 16. Qd4 cxd5 17. Qxh8 Qb6+ {Levy: I had completely overlooked this dreadful move. Now White is hopelessly lost. CHESS thought about this move for just two minutes, 81 seconds of which were on Levy's time. It valued the position at 5.17 pawns in favour of Black and remarked: "Oh, I had that!"} 18. Kf1 (18. Rf2 Qxb1+ 19. Rf1 Qb6+ 20. Kh1 Qe6 $19) 18... Qxb1+ 19. Kf2 Qxc2+ {Pfleger: Althought Black is threatened with mate in one (Qxg8), his extra knight, bishop and pawn are overwhelming. White is completely lost.} ({Levy: I was worried that} 19... Qb6+ 20. Kf1 Qg6 21. Rf8+ Ke7 22. Rxg8 Qf6+ {and not being able to avoid the queen exchange.}) 20. Kg3 Qd3+ 21. Rf3 Qxe4 22. Qxg8+ Kd7 23. Qg7+ {[#]} Kc6 { Levy: Makes the victory for Black more difficult. Pfleger: The king wanders out into enemy territory. Black should survive this daring excursion without damage, but 23...Kd6 would have made everything easier.} ({After} 23... Kd6 24. Qf8+ Qe7 25. Rf6+ Be6 {I would probably have resigned.}) 24. Rc3+ Kb5 25. Rb3+ Ka4 26. Qc3 Qg4+ {Pfleger: King on the rim is no sin!} ({With} 26... a5 { Black could have navigated past all dangers with 26...a5 and won the game.}) 27. Kf2 Qc4 {Levy: A precarious situation for Black.} (27... a5 {would have avoided the threatened loss of the queen and won the game for Black.}) 28. Ra3+ Kb5 29. Qa5+ Kc6 30. Rc3 Be6 {CHESS has seen the threatened loss of its queen too late. When the insight was necessary, in the 26th or 27th move, the program calculated ahead up to its 29th move. The next move, 30.Rc3, was not considered because it doesn't give check or capture a piece. The machine did not think it worthy of consideration.} 31. Qa4+ {At this stage the computer seemd not to be able to bear the loss of its queen. After a disconnect in the line from Cleveland it refused to continue playing. Only when CHESS operator Dr. David Cahlander, one of the developers of the Cyber 176 machine, reentered the position and typed in a number of parameters CHESS agreed to go on playing. } Kd6 32. Rxc4 dxc4 33. Qb4+ Kc6 34. Qa4+ {[#]} b5 {Levy: A very weak move. Now I suddenly had chances of winning. Pfleger: Black unjustifiably avoids the draw and plays this pawn advance. The next two moves of White turn the proud pawn phalanx on the queenside into a tattered skeleton. Dave Cahlander discovered the reason for this strange and unhealthy behaviour of the computer. After he had restarted the game on move 31, CHESS considered itself much stronger than Levy. The program had a "contempt" factor that influenced its stragegy according to the opponent. Due to a bad entry it believed it was 200 Elo points strong than Levy - in reality Levy was slightly higher. At the same time it thought it was slightly better in the game. So it decided to avoid the draw. The unfortunately loss of a pawn, the computer thought, could be easily compensated against the "patzer" on the other side of the board.} ({After} 34... Kd6) ({or} 34... Kb6 {I would have immediately gone for the repetition and considered myself lucky to draw the game.}) 35. Qa6+ Kd7 36. Qxb5+ Kd6 { Levy: Now I was quite sure I would win the game. I was in time trouble, but in this kind of ending I felt I was stronger than any computer.} 37. Qb4+ c5 38. Qd2+ Kc7 39. Qh6 Bg8 40. Qg7+ {Pfleger: In "Zeitnot" on move 40 Levy plays inaccurately. As so often in chess the threat of Qg7+ was stronger than its execution. The queen on h6 ties up the bishop, rook and king on the back rank. White should calmly advance his pawns on the kingside.} Kc6 41. g4 a6 42. Qf6+ Kb5 43. Qd6 Kb4 44. Qb6+ Ka3 45. Qc6 Rf8+ 46. Ke3 Rb8 47. Qxa6+ Kb2 48. Qd6 Ra8 49. Qd2+ Ka3 50. h4 Ra6 51. g5 Ra8 {Pfleger: The program is apparently baffled and moves its pieces erratically.} (51... Bf7 {is a serious alternative, to stop the advance of the white pawns.}) 52. h5 Re8+ {The game is taking too much time – it can go on for hours. Levy and Cahlander agree to end with the method used in the British championships: both players get a limited amount of time – in this case 15 minutes – to end the game or lose on time. The game continues at blitz speed.} 53. Kf4 Ra8 54. Ke5 Ra6 55. g6 hxg6 56. hxg6 Ra8 ({ Pfleger: Taking on g6 was impossible:} 56... Rxg6 57. Qc3+ Kxa2 58. Qc2+ { [%cal Rc2g6] winning the rook.}) 57. Kf6 Ra4 58. Kg7 Ra8 59. Qg2 Rd8 60. Qc6 Rd3 {61.Qa6+ and 62.Qb6+, and after 60...Rb8 61.Qc5:+ and 62.Qa7+ or Qe5+.} ({ Levy: The rook cannot hold the eighth rank due to the threat of} 60... -- 61. Qa6+ Kb4 62. Qb6+ {[%cal Rb6d8]}) ({and} 60... Rb8 {is met with} 61. Qxc5+ Kxa2 (61... Kb2 62. Qe5+ {[%cal Re5b8]}) 62. Qa7+ {[%cal Ra7b8]}) 61. Qa6+ Kb4 62. Kxg8 Ra3 63. Qb6+ Kc3 64. g7 Rxa2 65. Kf7 Rf2+ {[#]} 66. Ke7 {Pfleger: The queen sacrifice 66.Qf6 wins easily. At blitz speend the Scottish champion misses moves he would otherwise find quite easily.} ({CHESS, which had been egging its opponent on with remarks like "Be careful" and "How time flies", was expecting} 66. Qf6+ Rxf6+ 67. Kxf6 Kd4 68. Kf5 c3 69. g8=Q $18) 66... Rg2 67. Qf6+ Kc2 68. Qf5+ Kb2 69. Kf7 c3 70. Qe5 c4 71. Qb5+ Kc1 72. Qxc4 {[#]} Rxg7+ 73. Kxg7 {Pfleger: The nice rook sacrifice leads to a well-known drawn ending. A number of specatators were convinced that the game was winning for White, but in fact this draw has been known to chess theory for more than 100 years: in 1865 an almost identical position (wKg7, Qb7; bKc1, Pc3; White to play draws) was discussed in "The Chess World".} c2 {The theory of the endgame of queen vs pawn is discussed in Ludek Pachman's: "Endspielpraxis im Schach", p.40. He writes: "As a rule the queen wins, even against pawns on the seventh rank. The only exception is the rook and the bishop's pawns, but only if the defending king is on the seventh or eighth rank and the attacking king is far enough away." Of course CHESS knew nothing of this theory and considered itself – nine pawns behind – as totally lost. But it still defends the position in almost optimum fashion.} 74. Kf6 Kd2 75. Qd4+ Kc1 76. Ke5 Kb1 77. Qb4+ Ka2 78. Qc3 Kb1 79. Qb3+ Ka1 {Pfleger: Now the machine has found the correct strategy. It threatens to promote the pawn and exchange it against the the white queen. If White is able to capture the pawn on c2, CHESS will make sure its king is on a1, where it is stalemated. Levy tries the impossible, but the machine plays flawlessly.} 80. Qa4+ Kb2 81. Qd4+ Kb1 82. Qd3 Kb2 83. Qb5+ Kc3 84. Qc5+ Kb2 85. Qb6+ Ka1 86. Qg1+ Kb2 87. Qb6+ Ka1 88. Qg1+ Kb2 89. Qb6+ Ka1 {Three-fold repetition} 1/2-1/2

|

|